Manitoba

Kingdom of Manitoba La Royaume de Manitoba | |

|---|---|

|

Anthem: "Ô Manitoba" | |

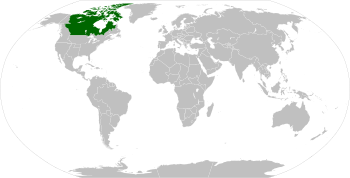

Location of Manitoba in North America | |

| Capital and largest city | Toscouné |

| Official languages | French, English |

| Demonym(s) |

Manitoban (English) Manitobain (French) |

| Supranational union |

|

| Government | Unitary parliamentary constitutional monarchy |

• Queen | Elizabeth II |

| Julie Payette | |

| Matthew McCarthy | |

| Benoit Tremblay | |

| Legislature | Parliament |

| Senate | |

| House of Commons | |

| Independence from Canada | |

• Establishment | TBD |

| December 11, 1931 | |

| April 17, 1982 | |

| TBD | |

| Area | |

• Total | [convert: invalid number] |

| Population | |

• 2020 estimate | 13,669,923 |

• 2011 census | 12,251,632 |

| GDP (PPP) | 2019 estimate |

• Total | 806.549 billion |

• Per capita | 59,709 |

| GDP (nominal) | 2019 estimate |

• Total | 725.894 billion |

• Per capita | 53,738 |

| HDI (2019) |

0.941 very high |

| Currency | Manitoban dollar ($) |

| Time zone | UTC -8, -7, -6, -5, -4 |

| Date format | dd-mm-yyyy (AD) |

| Driving side | right |

Manitoba, officially the Kingdom of Manitoba (Le Royaume de Manitoba), is a sovereign nation in North America. It is one of the three francophone nations in North America, the others being the Maritimes and Quebec. Manitoba shares land borders with British Columbia to the west, Superior to the south, and Quebec to the east; it shares a maritime border with Greenland (part of Scandinavia). With an area of X.X million km2 (X.X million sq mi.), Manitoba is the Xth-largest state in the world. Manitoba is relatively sparsely populated, with the total population estimated to be 12.91 million in 2020. Its capital and largest city is Toscouné, with the Toscouné-Fort Augustus Corridor boasting a population of 6 million. Other major cities include Ouinipignon, Sascoiton, Victoire, and La Reine.

Manitoba was historically part of New France. Manitoba was first explored by explorer Charles Nathaniel Godécque in the 1680s, who mapped the Nelson River basin in two expeditions and founded three major forts - one of which, Fort du Christ, would develop into the city of Ouinipignon (also known as Winnipeg). The colonial Manitoban economy was centered on the trade of furs and skins, especially beaver pelts. In 169X, after their attempts to settle in the St. Lawrence Valley were thwarted by Catholic authorities, a group of Huguenots led by Louis Guillaume settled modern-day Toscouné (though their original goal was to reach the Pacific Coast). The presence of Protestants in what was a strategically-important region (due to the prairie's agricultural potential) alarmed colonial authorities, who bolstered the number of Catholics in the region by converting the indigenous population and sending French settlers. While territorial expansion was relatively rapid, the Manitoban population (known in French as Les Manitobains) experienced rapid growth, the non-native population was no more than 14,803 by the last census (1754). Nevertheless, all of the 8 million Franco-Manitobans are descendants of this population.

After the Seven Year's War, much of French North America was ceded to Britain. The 1774 Canada Act affirmed the cultural autonomy of the French settlers. A unique social dynamic developed in Manitoba during the 18th and 19th centuries: the Anglo-Protestant minority dominated politics, the Franco-Protestant minority dominated commerce, while the Franco-Catholic majority was predominantly rural and involved in agriculture. Ethnolinguistic relations were largely cordial, with the Franco-Protestant minority serving as the "middleman" between the Franco-Catholic majority and the British administration. As a result, bilingualism was institutionalized early on, and the majority of Manitobans spoke both French and English. Manitoba did not partake in the Rebellions of 1837–1838. In spite of local opposition, Manitoba became part of the newly-formed Canadian Confederation in 1867. Politics was initially dominated by the Protestant minority, with policies such as literacy tests and poll taxes effectively disenfranchising most Catholics. Conflict between Protestants, who were generally richer, and Catholics manifested in the emergence and proliferation in militant farmer groups in the 1880s–1890s. Nevertheless, mass literacy and a growing Franco-Catholic middle class eventually led to anti-Catholic policies being discarded, and by 1900, Franco-Catholics constituted most of the electorate. In response, there was a reorientation of conservative politics from toryism to clericonationalism and Christian conservatism.

Starting from 1870, Manitoba entered a period of rapid economic growth, with its subsistence economy reorienting itself to commercial agriculture (thanks to the emergence of wheat as a major cash crop) and exploitation of natural resources such as timber, minerals, and oil. Rapid economic growth was accompanied by international immigration - mainly from Britain, Germany, Ukraine, and the American Prairies (mainly German and Scandinavian Americans). Reconciliation between Catholic and Protestant Manitobans, growing awareness of Manitoba's distinct cultural and sociopolitical history, a desire to define "who" is Manitoban in the face of international immigration, and border disputes with the Province of Quebec all contributed to growing national consciousness in the early 20th century.

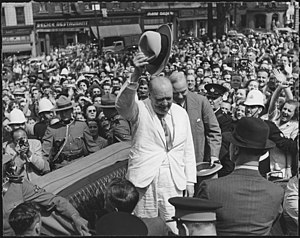

Great War I (1932–1938) resulted in the collapse of the Canadian Confederation, and the establishment of communist governments in Quebec, Ontario, and the Maritimes. British Columbia and Manitoba became their own dominions. Concerns about the expansion of Landonism led to a political shift to the right. In 1938, the Union Manitobain under Maurice Leclerc won in a landslide. The Union Manitobain ran on a combination of right-wing policies such as anticommunism and clericonationalism, and center-left economic policies influenced by Catholic social teaching. Its supporters were known as emmenistes from the party's initials. Fearful of an invasion from the United Commonwealth, Manitoba consolidated its ties with Britain and developed its defense capabilities. Jean-Claude Delacroix, considered Manitoba's best prime minister, was known for relaxing the party's social policies, while modernizing the economy in his "War on Poverty". He also led Manitoba's involvement in Great War II, which boosted its international presence. The Manitoba Miracle, underpinned by the discovery of oil, led to unprecedented prosperity. The political repression of the left and growing calls for societal reform led to a period of sectarian strife known as the "Tumultous Years" (Les Années Tumultueuse), during which various leftist militias waged a "low-level civil conflict". By the late 1980s, the Union Manitobain's popularity faced an all-time low. In 1990, Prime Minister George Kelly called a snap election, which ended in the collapse of the Union Manitobain and the newly-formed Bloc Manitobain (a merger of various opposition parties) winning majority in Parliament. Blanche Bessette thus became the first woman to be become prime minister.

Today, Manitoba is a highly-developed country with an advanced economy. As of 2019, Manitoba has a GDP (nominal) per capita of $53,738 and a GDP (PPP) per capita of $59,709, with the total GDP (nominal) and GDP (PPP) being $807 billion and $726 billion respectively. The mainstays of Manitoba's economy are oil, chemicals, and commercial agriculture; in recent years, aerospace, information and communication technologies, biotechnology, and the pharmaceutical industry play big roles in the economy. Manitobans enjoy one of the highest standards of living and is one of the most technologically-advanced societies, ranking within the top ten in the Human Development Index, life expectancy, educational attainment, and in the ICT Development Index. Despite a rather tumultous history in the 20th century, Manitoba is now considered a mature democracy, with an active civic culture and the population exercising numerous civil and political liberties. Nevertheless, Manitoba continues to be a conservative society and is one of the most militarized nations, with universal conscription for both its male and female citizens. Manitoba is currently going in a demographic shift due to immigration, and the Franco-Manitobans are expected to lose their majority by 2040.

Etymology

"Manitoba" is derived from either Cree manitou-wapow or Ojibwe manidooba. Both mean the "straits of Manitou, the Great Spirit", which refers to The Narrows at the center of Lake Manitoba (also called Prairie Lake / Lac des Prairies). It may also be derived from the Assiniboine minnetoba, which means "Lake of the Prairie".

History of Manitoba

Indigenous peoples and European exploration and settlement

Manitoba was first inhabited by the First Nations people (les autochtones Manitobains - "natives of Manitoba") after the retreat of the last ice age glaciers about 10,000 years ago; the first area to be exposed was the Turtle Mountain area. Groups that inhabited Manitoba by the start of European exploration and settlement were the Assiniboine, Cree, Dene, Mandan, Ojibwe, and Sioux peoples. Agriculture first arose along the Red River, where maize, beans, and squash (the Three Sisters) were cultivated. Native Manitobans lived a semi-sedentary lifestyle, and supplemented their agriculture with hunting and foraging. Other tribes also entered the area to trade fur and foodstuffs.

In 1522–1523, Italian navigator Giovanni da Verrazzano persuaded King Francis I of France to finance an expedition to find a western route to China. New France, France's colonial possessions in North America, was established in 1534 when Jacques Cartier claimed the land around the Gaspé peninsula (now in Quebec) in the name of Francis I. Early attempts at settlement failed, though French fishing fleets visited the area and fostered cordial relations with the natives (which contrasted with the English and Spanish relationship with their native subjects). In 1608, Samuel de Champlain established the Habitation de Québec, which was initially a trading outpost. They forged a trading and military relationship with Algonquin and Huron nations, with whom the French acquired furs and pelts in-exchange for scrap metal, guns, alcohol, and clothing. Territorial expansion was rapid, with courreurs des bois, voyageurs, and Catholic missionaries all taking part in the exploration and claiming of new land. The French established forts in the Great Lakes (by 1615), Hudson Bay (by 1659–1960), the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers (1682), and Saskatchewan and Missouri Rivers (1734–1738). The Hudson Bay watershed was claimed by the Hudson's Bay Company, administering the region (named "Rupert's Land") under the British.

From 1683–1686, Charles Nathan Godécque explored and mapped the Nelson River Basin. In 1685, he established Fort Ouinipignon (modern day Ouinipignon). Ouinipignon would later become the capital of the District of Manitoba. While the area was abound with furs and pelts, French colonial authorities initially did not pay much attention to Manitoba - instead consolidating their possessions in the St. Lawrence River Valley. In the 1680s, a group of Huguenots led by Louis Guillaume moved from New England to Quebec. After facing hostility from Catholic authorities (as the settlement of the region by non-Catholics was explicitly forbidden), they moved westwards - settling Toscouné in three separate expeditions by 1695. The news of a successful Huguenot settlement in a strategically important area (due both to the fur trade, and the prairie's agricultural potential) led to more earnest attempts at settlement of Manitoba. In the 1720s, the King sponsored the passage of 1,600 women (twice sent to Quebec) to Manitoba, with the majority ending up either in Toscouné or Ouinipignon. While population growth was high, total settlement was low, with only a total of roughly 4,000 Frenchmen in total permanently settling in Manitoba before 1763 (half of the number that settled Quebec). Nevertheless, the 7 million Franco-Manitobains are descended from this population and another small stream from Quebec in the period 1763–1775.

Manitoba's colonial economy was fuelled by the North American fur trade and by the cultivation of wheat for profit. By 1754, about 5,600 tons (enough to support 14,000 people) of unhusked wheat had been transported to other parts of New France - most arriving in either the St. Lawrence Valley or to Louisiana via the Misssissippi River. Toscouné and Ouinipignon were the main urban centers: Toscouné processed grain, while Ouinipignon was the main trading center for furs and skins. Manitoba's economic potential was not fully harnessed, however, due to a dispersed population (which owed itself to a low rate of immigration). Relations between natives and the Franco-Manitobains were largely cordial, with the Plains Indians (such as the Cree) trading furs and skins in-exchange for guns, scrap metal, and alcohol. Many French men, especially prior to the arrival of the filles du roi, also took native wives. The multiracial métis group are the result of these interracial marriages, as well as the broader phenomena of the North American fur trade.

Seven Years' War

The population of New France was quite low compared to British North America, with non-natives in New France numbering less than 100,000 by the 1754 Census (the last one conducted before the Seven Years' War). French attempts to expel British traders and colonists from the Ohio Valley led to a surprise attack by George Washington on a group of French soldiers sleeping in early morning hours (later known as the Jumonville affair). There was no declaration of war issued by either country, though by 1756, the Franco-British tensions escalated to a global war. In 1758, the British mounted an attack on New France and took French-controlled Louisbourg. The Treaty of Paris (1763), which concluded the conflict, transferred control over most of French North America (except Saint Pierre and Miquelon) to the British in-exchange for Guadeloupene; French Lousiana was ceded to Spanish in the secret Treaty of Fountainebleau.

Quebec Act and American Revolution

With brewing discontent in its American colonies, the British were worried that the 100,000+ "Canadians" (Canadiens) of Quebec and Manitoba (then organized into the Province of Quebec) would join the rebellion. British immigration was low, hence people of French descent continued to dominate the population. Governors James Murray and Guy Carleton promoted the need for change - culminating in the enactment of the Quebec Act of 1774. This preserved French culture and language, allowed French speakers to practice French civil law (as opposed to British common law), and guaranteed freedom of religion. Nevertheless, there was still some conflict between the French-speaking majority and incoming British settlers, which was religious in nature in Manitoba (Protestants versus the Catholics), and more so linguistic/cultural in Quebec (French speakers and English speakers).

The Quebec Act also forbade American settlement into the Province of Quebec. This, together with the recognition of the Catholic Church, angered many Americans (though it is not regarded as one of the Coercive Acts). The United States attempted to conquer Lower Canada, with General George Washington and his Continental Army invading Quebec starting June 27, 1775. British reinforcements arrived in May 1776, and the Americans were soundly routed in the Battle of Trois-Rivières. The Canadiens were largely ambivalent to the American cause, with the punishment of American sympathizers further deterring them from joining against the British. Frederick Haldimand replaced Guy Carleton as Governor of Quebec in 1778.

10,000 loyalists arrived in Quebec following American independence, with more arriving until 1815. Only a few of these settled Manitoba, and the Anglo-Manitobains never comprised more than 10% of the population prior to 1870 (when immigration started surging). Most of them settled in Ontario, with concerns over the relations between the English and French settlers prompting the division of the province of Quebec in 1791 into three regions: French-speaking Manitoba and Lower Canada (Quebec), and English-speaking Upper Canada. A this point, Quebec and Manitoba started to diverge culturally, with Manitoban culture being strongly influenced by the Plains Indians and métis, and the traditions of the Huguenot minority.

Province of Manitoba (British Crown Colony)

- Main article: Province of Manitoba (1795–1867)

English settlement continued to be quite low. Their population stabilized at 10%, with immigration being offset by the high birth rates of the Franco-Manitobains (especially the Catholics). In the early 1800s the average Franco-Manitoban woman had 8 children, this was lower still than the figure (10 births per woman) during the 1700s. The English were primarily concentrated in Toscouné and Ouinipignon, as the Franco-Manitobans were more inclined into living in rural regions. Their demographic minority meant they learned French and accomodated French culture (such as civil law, and to an extent, the presence of Catholicism), which was unlike the situation in Canada. In addition, they relied heavily on the Huguenots (which were a similarly-sized minority) for commerce and administration as "middlemen"; their Protestant faith allowed them to connect to the English, while their French cultural heritage allowed them to connect to the French Catholics.

Manitoba did not participate in the Lower Canada Rebellion (1837–1838), despite being predominantly French-speaking (~90%) and Catholic (~80%) like Quebec. This was probably because seigneural landowners as well as the institution of the Catholic Church were much weaker than in Quebec, though still prominent. Furthermore, Anglo-Manitobains were well-integrated into francophone society and were more receptive to a bilingual language policy, while English-speaking Quebeckers lived in enclaves where they did not perceive a need to learn French. Nevertheless, Manitoba was mentioned (albeit briefly) in Report on the Affairs of British North America. The Act of Union (1841) consolidated Manitoba, Lower Canada (Quebec) and Upper Canada (Ontario) into the Province of Canada, per the suggestion of Lord Durham. All Manitobains were opposed to this: the Franco-Manitobains did not want English supremacy, while the Anglo-Manitobains believed the influx of more English settlers would weaken their unique position in Manitobain society. The Province of Canada inherited Manitoba's land conflict with the Hudson's Bay Company (HBC), which the British government initially ruled in favor of the latter. However, much of what is now northern Manitoba would be taken back from the HBC in the Rupert's Land Act 1868.

Unlike in the St. Lawrence Valley, there was no perceived shortage of land. Relations between White and Native Manitobains continued to be cordial. Native Manitobains continued their way of living until the late 19th century - largely undisturbed. The growing non-native population (especially the influx of English settlers starting 1830) eventually led to greater contact between them and White Manitobains. Resurgent demand for furs and the booming alcohol trade led to competition and conflict between the Native Manitobains, which was facilitated by the increasing availability of guns. The last major conflict fought between Native Manitobains was the Battle of the Belly River in 1870 - fought between the Cree and the Blackfoot Confederacy. The use of guns also led to the overhunting of bison (the primary food source of Plains Indians), which coupled with heightened incidence of disease, ultimately decimated the Native Manitobains population.

Province of Manitoba (part of Canadian Confederation)

- Main article: Province of Manitoba (1867–1919)

In July 1, 1867, the provinces of Manitoba, Canada, New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia united into the Dominion of Canada. This was a culmination of a process referred to as Canadian Confederation. The formation of Canada was motivated by concerns with American expansion northward, and the desire of British–Canadian nationalists to create one state dominated by British culture and the English language. In Quebec and Manitoba, which both had francophone majorities, a decentralized union was seen as more favorable to centralized rule. At the time of unification, Franco-Manitobains comprised 80–90% of the total population; the anglophone minority was concentrated in Toscouné. Manitoba continued to experience rapid population growth into the 19th and 20th centuries, due to high natural growth and international immigration. Despite having just 14,000 people at the time of British handover (compared to Quebec’s 65,000), Manitoba would surpass Quebec’s population by the 1950s.

The 72 Resolutions did not identify Manitoba as part of a Franco-Canadian “homeland”, thus, its cultural independence was not guaranteed. Unlike in Quebec, however, bilingualism was institutionalized early in Manitoba’s history, resulting in a population that was uniquely fluent in both French and English. Societal tensions were instead sectarian in nature. Sectarian tensions arose from Protestant dominance of politics and the economy, while the Catholic majority (70-80%) remained predominantly rural and poor.

In 1867, Pierre Cartier became the first premier of Manitoba, running under the platform of agricultural development. Unlike succeeding elections, large numbers of Catholics voted - nevertheless, Protestants were disproportionately represented due to access to voting booths. Pierre Cartier made sure to steer of any religious affairs, as to not incite any intersectarian conflict. Nevertheless, in the 1870s and 1880s, the Catholic Church in Manitoba worked to extend its influence among Manitoban Catholics: they operated institutions such as schools, hospitals, and charitable organizations. Despite their lower political status, Catholic voters managed to secure the enshrined status of churches in society and ecclesiastical influence in family law, which effectively enabled the Catholic Church to regulate matters such as family registration, marriages, divorce, and custody in their own terms.

At the time of Confederation, Manitoba was moderately urbanized, with its population being concentrated into a handful of big cities and towns. Manitoba’s largest cities were Touscouné and Ouinipignon, with the former having 30,000 and the latter about 20,000. By 1900, Toscouné had about 400,000 people, or about just below a third of the total Manitoban population. Despite its relative isolation, Toscouné emerged as a major city due to its centrality in Canadian railway. Toscouné lost its Franco-Catholic majority by this time, with the neighboring city of Augustus having an Anglo-Protestant majority. Ouinipignon declined relative to Toscouné, but became known as the epicenter of “Old Manitoban” culture.

The construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway, which went through Toscouné connected the western and eastern halves of Canada and opened the Canadian Prairies to mass settlement. Construction was completed by 1885, in spite of a Métis rebellion led by Louis Riel. It is around this time when international immigration started to boom. Due to the closing of the American frontier c. 1890, many Americans crossed the border in search of land. The largest of these settlers were German–Americans, with up to 600,000 coming between 1880 and 1920. Germans generally came as independent farmers, and integrated themselves into the Franco-Catholic rural majority while maintaining their religion. The entry of Americans brought ideals such as liberalism, individualism, and egalitarianism, whereas other Canadian provincial politics revolved around toryism and socialism. Social liberalism, individualism, and egalitarianism (especially in respect of socioeconomic justice and nonsectarianism) heavily influenced liberalism in Manitoba, while Manitoban conservatism became a synthesis of social conservative and center-left economic policies.

The administration of Jean-Baptiste Goedeke-Williams, which spanned the 1880s and coincided with the influx of international migrants, saw the rapid economic development of Manitoba. The election of Jean-Baptiste was controversial due to his purported use of gerrymandering, with Protestant-majority districts receiving more electoral weight than Catholic-majority districts. The Manitoban economy rapidly grew due to the export of wheat, and to a lesser extent, the railway industry and resource exploitation. Nevertheless, exceedingly high grain prices agitated some non-farming Manitobans, resulting in the establishment of militant farm organizations such as the United Farmers of Manitoba (UFM) in 1895. Partly in reaction to this, the following year, the Conservative Party of Manitoba implemented the first set of voting restrictions which effectively disenfranchised over half of Catholic Manitobans. Since many immigrant farmers joined these organizations, xenophobic attitudes grew among the native-born population - especially among British Manitobans. Nevertheless, the fear of American annexation and a desire to consolidate control over Manitoban territories gave way for the further liberalization of immigration laws.

By the 1900s, politics became divided between the Conservative Party and the Liberal Party, with minor parties representing the interests of farmers (United Farmers of Manitoba) or that of ethnic minorities (Ukrainian Manitoban Front, German-Manitoban Party). Manitoban conservatism had become characterized by a support of the church and of social conservatism, as well as center-left economics from both Catholic social teaching and Protestant social gospel. By 1920, only about 1/3 of Catholics were enfranchised. Despite the disenfranchisement of Franco-Catholics, the Catholic Church supported the Church-friendly policies of the Conservative Party, while continuing to speak on the socioeconomic and sociopolitical discrepancies between Catholics and Protestants.

From 1900–1930, immigration continued. It became increasingly evident, however, that the Franco-Catholic majority, due to their fecundity, would prevail. Manitoban politicians instead became preoccupied by consolidating provincial identity. Manitoban identity became centered around bilingualism - the acquisition of both English and French - and Christianity. This was different from in Quebec, where a francophone identity was paired with a Catholic one. A central figure in defining Manitoban identity was Venceslas Dulac, who was the premier from 190X to 191X. He emphasized the “difference” between French-speakers in Quebec and in Manitoba, positing that the latter, due to their distinct history and differing origins, constitutes a related but distinctly unique cultural unit. He bemoaned attempts from Quebecois politicians to promote Franco-Canadian nationalism: in spite of this, he consolidated French language education and tolerated the dominance of the Catholic Church, similar to his contemporaries.

Manitobans’ desire to differentiate themselves from the francophones of Quebec manifested itself during the Second Boer War, in which the Quebecois challenged the British government’s request to send a militia to fight in its behalf. In contrast, the Manitoban premier at the time did not hesitate sending Manitoban soldiers, despite the greater geographical distance. The Catholic Church in Manitoba also defended the military support of Britain and its allies, unlike the Quebec Church. Conflict between Manitoba and Quebec arose after the Quebec Boundaries Extension Act 1912, which gave the District of Ungava to Quebec, despite it historically being a part of the Province of Manitoba (Manitoba agreed to relinquish control over the region after confederation). Manitoban frustration with this territorial “grab” would culminate in the Nipissingville Riots of 1913, which would permanently sour relations between Quebec and Manitoba. Attempts to challenge Quebec’s annexation of Ungava (renamed into Quebec du Nord) would be unsuccessful, with the area only returning to Manitoban rule after the Crimson Spring; this conflict would prove instrumental in cementing the political distinction between Quebec and Manitoba.

Dominion of Manitoba

Great Depression, Crimson Spring, and the rise of the Union Manitobain

- Main articles: Great Depression in Manitoba, Crimson Spring

The Great Depression hit Manitoba hard, due to the collapse of wheat prices and a regional drought affecting Palliser Triangle from 1916 until roughly 1926. Unemployment soared to about 10%, however this understates urban unemployment, which reached 30–50%. Together with the Crimson Spring (1932), the tough economic conditions of the Great Depression led to a political shift to the right. Clericonationalism and ultraconservatism became the mainstream political currents, with liberalism becoming secondary and becoming largely limited to urban Anglo- and German-Manitobans. The Spanish Civil War and religious purges in the United Commonwealth alarmed devout Catholics and Protestants alike, leading to an association of atheism with socialism and other left-wing political movements.

The Crimson Spring (1932) also led to the de facto dissolution of the Dominion of Canada. The remaining two provinces, British Columbia and Manitoba, became their own dominions the following year, with the Premier of Manitoba becoming the Prime Minister of Manitoba. The Northern Territories and Ungava (Nord du Quebec) were granted to Manitoba, thus giving Manitoba access to a port in Hudson Bay.

In 1932, the newly-formed Union Manitobain won a majority in parliament. The Union Manitobain (UM) was a right-wing party which championed clericonationalism, ultraconservatism, and opposition to left-wing ideologies. Its supporters were called emmenistes. Maurice Leclerc led the UM, and was regarded as a grandfatherly figure. The UM exploited mistrust of left-wing (including liberal) ideologies to steer focus away from the Catholic–Protestant conflict. Middle-class Catholics, who formed 1/3rd of the population and were largely enfranchised, played a key role in attaining emmeniste support among the Catholic majority. Despite Protestant dominance of party leadership, elements of Catholic social teaching influenced the politics of the Union Manitobain. These included the principle of the preferential option for the poor, and support for a communitarian form of democratic capitalism.

Manitoba was partially insulated from the Great Depression due to the more ruralized character of its economy and population. The economy recovered to pre-crisis levels c. 1933, and became to experience growth up to the onset of the First Great War. Most of this growth can be attributed to a shift from wheat exports to industry, both due to internal producers making up for the shortfall in consumer goods, and due to manufacturing of arms, vehicles, and steel in anticipation of a future conflict with the United Commonwealth.

Great War

Manitoba's involvement in the Great War began when...

Out of a population of around X million, about X00,000 Manitoban men (alongside X0,000 women auxiliaries) served in the armed forces in the Great War.

Much of eastern Manitoba, including the then-capital of Ouinipignon, and the sparsely populated but strategically important regions of Nord-d'Ontario and Ungava (now Quebec-Oueste), was overrun by the United Commonwealth during the GreatWar. As a result, the Manitoban government temporarily relocated (and later, permanently) to Toscouné. The occupation of Manitoba's Hudson Bay ports essentially isolated Manitoba from the rest of its allies - including its traditional protector, Britain.

The Manitoban Campaign eventually faltered, with victory in the Battle of TBD thwarting further Continental advances. The widely dispersed nature of Manitoba's population centers aided its defense. In addition, by 194X, the United Commonwealth was bogged down in the Rockies while also facing an increasingly restive Superian and Brazorian population.

Kingdom of Manitoba

Interbellum

- Main article: Interbellum in Manitoba

The Interbellum (1946–1961) spanned the tenures of two prime ministers: Adrien Thibodeaux (until 1951), and Jean-Claude Delacroix.

Second Great War

Cold War

Les Années Tumulteuses

1990s

Manitoban Revolution

Modern era

Politics

Manitoba is a parliamentary constitutional monarchy. The head of state is Queen Elizabeth II, of the House of Windsor-Mountbatten. The head of government is Prime Minister Matthieu McCarthy. Legislative elections are done every 4 years, with the next election being in 2022.

Manitoba has a three-party system. The three foremost parties are the liberal-conservative Bloc Manitobain, the center-right Conservative Party, and the center-left Liberal Party.

Monarchy

- Main article: Monarchy of Manitoba

Administrative divisions

Canadian reunification

- Main article: Canadian reunification

Canadian reunification is an irredentist movement that seeks to reestablish the Canadian Confederation through the unification of the Canadian successor states. Canada lasted from 1867 (with the unification of the provinces of Canada, New Brunwick, and Nova Scotia), until the Landonist Revolutions of 1919–1921, which saw the Maritimes, Ontario, and Quebec falling under the control of communist governments. Astoria, Manitoba, and the Yukon Territory continued to be ruled by the British, though separately. Another form of Canadian reunification involves unifying the Canadien (Franco-Canadian) population of Manitoba, the Maritimes, Quebec, and Yukon while excluding the primarily-English speaking states of Astoria and Ontario. Despite historically gaining widespread support during the 1930s to 1960s (in the height of Manitoba's anticommunism and conservatism), currently both forms of Canadian reunification are not endorsed by any major political party.

Eastern alienation

- Main article: Eastern alienation

In Manitoban politics, Eastern alienation (L'aliénation de l'Orient) is the notion that East Manitoba have been increasingly alienated or excluded from mainstream Manitoban political affairs in favor of West Manitoba, centered around the Toscouné–Fort Augustus Corridor. Eastern alienation claims that while Ouinipignon is the capital, the government is excessively centered around West Manitoban affairs, which holds most of the population (slightly less than 60%) and economy. Eastern alienation is sometimes tied to nativism and anti-immigration, as Toscouné and Fort Augustus have a larger proportion of first-generation and second-generation Manitobans and allophones (people whose mother tongue is neither French or English).

Demographics

- Main article: Demographics of Manitoba

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1686 | 57 | — |

| 1692 | 249 | +336.8% |

| 1706 | 1,341 | +438.6% |

| 1713 | 1,865 | +39.1% |

| 1720 | 2,483 | +33.1% |

| 1727 | 4,635 | +86.7% |

| 1734 | 6,966 | +50.3% |

| 1739 | 8,548 | +22.7% |

| 1754 | 14,803 | +73.2% |

| 1765 | 22,077 | +49.1% |

| 1784 | 45,470 | +106.0% |

| 1790 | 57,088 | +25.6% |

| 1806 | 101,973 | +78.6% |

| 1814 | 134,652 | +32.0% |

| 1822 | 173,872 | +29.1% |

| 1831 | 227,804 | +31.0% |

| 1844 | 337,189 | +48.0% |

| 1851 | 415,628 | +23.3% |

| 1861 | 554,230 | +33.3% |

| 1871 | 726,771 | +31.1% |

| 1881 | 897,676 | +23.5% |

| 1891 | 1,132,576 | +26.2% |

| 1901 | 1,432,564 | +26.5% |

| 1911 | 1,951,568 | +36.2% |

| 1921 | 2,874,854 | +47.3% |

| 1931 | 3,505,205 | +21.9% |

| 1941 | 3,945,679 | +12.6% |

| 1951 | 4,626,746 | +17.3% |

| 1961 | 5,705,728 | +23.3% |

| 1971 | 6,751,650 | +18.3% |

| 1981 | 7,825,684 | +15.9% |

| 1991 | 9,130,232 | +16.7% |

| 2001 | 10,607,170 | +16.2% |

| 2011 | 12,251,632 | +15.5% |

| 2020 (est.) | 13,669,923 | +11.6% |

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 2021 | 13,833,627 | — |

| 2031 | 15,533,128 | +12.3% |

| 2041 | 17,195,047 | +10.7% |

| 2051 | 18,736,479 | +9.0% |

| 2061 | 20,216,633 | +7.9% |

In the 2011 Census, Manitoba had a population of 12,251,632, a 15.5% increase from its 2001 population of 10,607,170. With a land area of X.X million km2 (XXX,000 sq mi) it had a population density of X.X/km2 (X.X/sq mi) in 2015. The country's population is expected to reached 13,833,627 by the 2021 Census. Manitoba's population growth rate (1.2% as of 2019) is one of the highest among developed countries, due to substantial immigration (which accounts for just under half of the total growth) and high fertility until recently. The population is expected to hit an excess of 20 million by 2061.

At 1.90 births per woman (2019), Manitoba's fertility rate is lower than the replacement fertility rate of 2.1. This is higher than the OECD average (~1.6), and the average for both North America (<2) and Europe (~1.5). Manitoba historically had one of the highest fertility rates of any industrialized society, peaking at 4.31 in 1958. This declined to 2.38 by 1990, but remained well above replacement fertility until the 2010s in the aftermath of the Great Recession. Life expectancy is 82.3 years as of 2015, with the elderly comprising 14.7% of the population, thus making Manitoba an aging society.

Ethnicity

Future

The Franco-Manitoban population is expected to lose its majority by 2040, despite a net increase of nearly a million people from 2020 (7.6 million to 8.5 million).

Language

- Main articles: Language in Manitoba, Manitoban French

Manitoba recognizes two official languages: English and Manitoban. The prestige variety of Manitoban English is not too dissimilar to other Anglo-American accents. The vernacular variety of Manitoban English, however, is influenced by French lexicon and phonology. Manitoban French is similar to other varieties of North American French. Manitoban French can be split into two varieties: Western and Eastern. Western Manitoban French is largely identical with French in Quebec, save for a few words and the more frequent occurrence of anglicisms. Eastern Manitoban French, also called Red River French, is more similar to the now nearly-extinct Missouri French dialect (such as in its use of "z" in bonjour, resulting in it being pronounced "bonzour"). Metropolitan French, however, is the variety used in mass media and in public life.

Manitoba has been bilingual since its establishment as the Province of Manitoba in the late 1700s. In spite of efforts to repeal the official status of French in the early 20th century, antagonism against the French language was weaker than in other parts of Canada. The vast majority of native-born Manitobans are fluent in both French and English. There is also a large population of xenophones or people whose native language is neither French nor English. "Code-switching" between French and English is common, as is the presence of anglicisms in French and Frenchisms in English. The latter phenomena are somewhat of a concern as it can prevent people - especially immigrants - from attaining sufficient fluency in either language.

Religion

- Main article: Religion in Manitoba

Manitoba remains a predominantly Christian country. It is the most religious country in the OECD alongside Tondo and Mexico, with over 90% of the population professing a belief in God and a church attendance rate of 40-50% in recent years. This is in spite of the recent trend of liberalization, and the decline of the Catholic Church's role in society. Catholics comprised 55-60% of the population, and are represented largely by French Manitobans; other major Catholic groups include Irish, Italian, German, Tondolese, and Native Manitobans. 30% of the population is Protestant, with most either being Calvinist (mainly French Manitoban), Anglican and Presbyterian (mainly Anglo-Manitoban or Scots-Irish Manitoban), and Lutheran (mainly German Manitoban). A significant minority of Seventh Day Adventist's exist as well. Other Christian groups comprise the remainder. This includes the Eastern Orthodox - who are primarily of Ukrainian descent, and nontrinitarian churches such as Mormons and Jehovah's Witnesses. Less than 10% of the population is non-Christian. This includes Jews, Muslims, Hindus, and Buddhists. Most irreligious Manitobans are of Asian descent, though second-generation Asian Manitobans are more likely to convert to Protestantism or form ethnic churches.

Ideas

- CONFLICT

- between catholics & protestants

- language not an issue due to early bilingualism

- protestant dominance (anglo-manitoban/huguenot manitoban)

- common support for anticommunism, antiliberalism, and antisecularism > mixed Union Manitobain

- catholic support for UM dwindled by 1990s

- cultural regions

- toscouné

- quarters of toscouné:

- english quarters

- huguenot quarters

- creole quarters

- catholic quarters

- quarters of toscouné:

- ouinipignon

- english town

- french town

- creole town

- prairie (saskatchewan)

- ukrainian manitobans

- german manitobans

- reservations

- historical division into "two societies"

- urban society

- british - administrative class

- huguenots - financial/professional class

- black (creole) - artisanal class

- rural society

- clergy

- landlords

- peasantry

- first nations - marginalized minority

- the british/huguenots dominated manitoba politically, historically

- combination of apathy, poll taxes, literacy tests

- the huguenots were protestant like the anglo-manitobans, but french-speaking like the franco-manitobans

- thus all prime ministers were huguenots

- les perturbances

- instigated by the catholic liberation front (front de liberation catholique - FLC)

- leftist tendencies

- goals

- want end to huguenot-british dominance

- want the weakening of catholic church (viewed as complicit with huguenot-british dominance)

- catholic church condemned the movement

- mixed public support

- many moderate catholics view it as subversive

- most support - young urban, working-class catholics

- history

- 1800s

- manitoban nationalism

- common identity fostered easily

- continued tensions between prots and catholics (mitigated by huguenots)

- 1870 - dominion of manitoba

- 1880s

- allophone migration encouraged

- esp. brits, germans, scandinavians - later ukrainians, italians, irish

- franco-manitobans:

- 1850 - 90%

- 1900 - 80%

- 1920 - 60% (nadir), before restricted immigration (both anglo and french backlash)

- 1970 - 68%

- 1930s

- great depression

- foundation of union manitobans - french catholic, french huguenot, and anglos united in common identity

- stress ultraconservatism, anticommunism, antisecularism

- catholic-protestant relations are put at the backburner

- foundation of the manitoban catholic liberation front, against perceived catholic oppression

- 1930s–1990s

- manitoban catholic liberation front (front de liberation catholique manitobaine) slowly become more moderate, gain more mainstream popularity

- 1960s–1990s

- union manitobain continue to dominate politics

- concessions from anglo and huguenot manitobans to catholic french manitobans majority

- economic development programs

- anti-discrimination laws

- industrialization & urbanization

- 1990s

- crisis between religious groups

- manitoban catholic church switch positions - used to be complacent w/ anglo-huguenot dominance

- ending w collapse of union manitobain, creation of bloc manitobain

- first woman of color as prime minister

- language

- 70% of manitobains have basic english proficiency

- "franglais" in informal media; french in formal media

- code-switching phenomenon

- concern about decline of english quality

- concern about anglicisms

- economy

- historically, exporter of wheat, forest products, and beef/cattle products

- now : energy (oil, natural gas)

- GDP per capita (2019) ~ $59708.75 (basically, albertan gdp/c + average of manitoban and saskatchewan gdp/c)

- military

- universal conscription

- enacted in 1930s

- british bases in ungava & hudson bay area

- close ties w/ britain & sierra

- city in ungava

- use pics of murmansk

- historical british base

- pop = 200k