Ancient Orat (Project Exodus)

Kingdom of Orat | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2300 AA–372 AA | |||||||||||

|

Orat never had a national flag, but this modern recreation combines symbols typically found in royal standards | |||||||||||

| Capital |

Dhiss Former capitals including: Nodh, Nada, Bast, Xios, Ankho, and Zoan | ||||||||||

| Common languages | Various North Methonan languages including Oratian, Kalleanite, Mammonite, and Vaninite | ||||||||||

| Religion | Douism, Kalleanism, Ona, and local animist religions | ||||||||||

| Demonym(s) | Oratian | ||||||||||

| Government |

Absolute Monarchy Douist Society | ||||||||||

| Shada | |||||||||||

| Viceroy | |||||||||||

| Historical era |

Bronze Age Iron Age | ||||||||||

• Nodh Culture | 2300 AA 2300 AA | ||||||||||

• Unification of Upper and Lower Orat | c.1800 AA | ||||||||||

• Apef the Terrible | 1460-1428 AA | ||||||||||

• Kalleanite Exodus | 1112 AA | ||||||||||

• Norin War | 786-779 AA | ||||||||||

• Zoan Kingdom independence | 551 AA | ||||||||||

• Conquest of Orat by Olric II | 460 AA | ||||||||||

• Disestablished | 372 AA | ||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||

• 1800 AA | 800,000 | ||||||||||

• 1300 AA | 1.6 million | ||||||||||

• 950 AA | 2.4 million | ||||||||||

• 400 AA | 15 million | ||||||||||

• 300 AA | 3 million | ||||||||||

| Currency | none (gold and silver bullion) | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

Ancient Orat was a civilization of Ancient Methona, concentrated around the Kera River Valley between the Draffa Mountains and the Ubiud Sea. The region now known as Orat has been home to some of the oldest recorded civilizations in the world, starting with the Nodh Culture that emerged around 2300 AA. The ancient history of Orat begins around 1800 AA in the Middle Bronze Age, with the political unification of Upper and Lower Orat under Mino, the first Shada (or King). Traditionally, Ancient Oratian history is considered to end in 460 AA after Olric II established the Oratian Empire, which marks the beginning of the Venerable Era. This history is typically divided into broad eras distinguished by major shifts in socio-political systems and material culture, referred to as the Old Kingdom (1800-1450 AA), Middle Kingdom (1450-1100 AA), New Kingdom (1100-780 AA), and Late Kingdom (780-460 AA). During the Venerable Era, Orat was ruled by the Ruminid Dynasty that held the title of Shada up until the region's annexation by the XXX Empire in 183 AA.

Ancient Orat is best known for their unique social, economic, and religious systems that were unlike most other civilizations of its day, and had a major impact on subsequent societies in that same region. Much of Ancient Oratian society revolved around the Douist religion that emerged sometime around the Middle Kingdom, and remains an important religion of Orat to this day. The political history of Orat is mostly defined by a sequence of absolute monarchs bearing the title Shada, who ruled at the behest of influential Douist philosophers. The economy of Ancient Orat, relying on an unpaid collectivist labor force called the Miqta System, was also unique for its day, and remains a subject of ongoing economic study. The history of the Kalleanites is likewise closely tied to that of Orat, which eventually reached its apex during the Oratian Empire. During the Venerable Era, Orat also played an instrumental role in the spread of the Axiomatic Revolution.

Ancient Orat is also responsible for many important innovations regarding science, mathematics, art and architecture during the Old and early Middle Kingdoms, which subsequently disseminated to the rest of the known world. In particular, the Great Pyramids of Orat built during the Middle Kingdom are one of the wonders of the ancient world, and an icon of Methonan civilizations.

Assessment of Ancient Oratian history is a subject of great controversy among the modern academic elite in modern Orat. Douist scholars have a mostly positive view, and see the civilization as a cultural Golden Age in which the Douist ideals of collectivism, secularism and social equality were best implemented. However, Melchian theologians and other Kallean-based religions have a very negative view, and describes the civilization as a lawless and tyrannical slave society inundated with exploitation and hedonism. This controversy is one component of the greater Doutang debates that continues among Oratian academic elite.

Etymology

The Oratian word 'at or 'ath derives from the Proto-Methonan root suffix *-anth, which is universally used to refer to man, people, or humanity. This is often compared to the legendary figure An (the first man in Kalleanite scriptures), or the suffix -atti commonly used to refer to a specific group of people.

The word orr or wawrr is a far more obscure origin, that continues to be a subject of research. Typically, academic sources translate this word as "union" or "unity", comparing it with the obsolete word warr used to refer to the numeral one. Looser translations have rendered this word as "collective" or "society". Consequently, various sources have interpreted the name Orat to mean either "unity of people", "collective of people", "people's society", or "oneness of workers".

However, primary sources on the translation of wawrr are considerably rare. While the word does appear in a few inscriptions from the Middle Kingdom, the direct etymology of Orat is first given in religious texts from Douist philosophers of the New Kingdom, particularly that of Konnu the Wise. Some scholars, particularly outside the Douist academic elite, have theorized this interpretation is actually a folk etymology. In reality, the Oratian people were originally distinguished by the letter waw in their alphabet which was unknown in most Methonan phonologies, and so the nation became commonly referred to as "people of the waw".

In modern Douist texts, the word "Orat" is used to refer to the hypothetical concept of the ideal World State, in which all social structures and religions are broken down and absorbed into the oneness of the Social Dou. The relationship between the idealized concept of Orat and the historical Oratian state in antiquity is a key point in the ongoing Doutang debates. Mainstream Douism maintains that the nepotism, human sacrifices and child abduction during Ancient Orat, although practiced frequently, do not reflect the ideal World State. More extreme apologists have questioned how frequently these practices took place, and argue these were not as inhumane as the discrimination and pogroms that occurred under the Oratian Empire.

Geography

Orat is typically referred to as the "Gift of the Kera". Early on, especially during the Old Kingdom, much of Orat's society, material culture and technology revolved around the ability to irrigate crops using the seasonal floodwaters of the Kera River valley. The Kera River starts in the Draffa Mountains, most likely originating from melting snow, and then curves towards the east that defines the southern border of Upper Orat. The Kera then moves back to the west, before flowing straight north in a way that bisects both Upper and Lower Orat, and branches into smaller tributaries. It then splits into a delta in Lower Orat, finally depositing into the Ubiud Sea.

The coast of the Ubiud Sea marks the northern border of Orat, although the Oratians never constructed a navy outside of basic fishing ships until the Venerable Era. Beyond the Ubiud sea north of Orat is the XXX Peninsula, which were likely little more than hunter-gatherers for most of Pre-Venerable History.

The east and southeastern borders of Orat marks the beginning of the massive Skypriot Plains, from which the kingdom was frequently raided by nomadic groups. The Cyr River is found several hundred kilometers southeast of Orat. This river also begins in the Draffa Mountains, running generally east before depositing into Cyro Lake. The Cyr River Valley is the heartland of the Skypriot Empire, which was instrumental in the formation of the Oratian Empire in the 5th century AA. Beyond the Cyr River is the Central Methonan steppes, which constitutes the homeland of all Skyprio-XXX Peoples.

The Draffa Mountains continues beyond the south and southwestern borders of Orat for hundreds of kilometers, including some of the tallest mountains in Methona. The uncertain origin of the Kera River heightened a sense of mystery that captured the imagination of ancient mythology, who described the Draffa Mountains as home of various deities or demigods. This tradition died out in Orat with the rise of Douism, but Kalleanite scriptures claim this to be the location of the "Garden of Life" where the legendary patriarchs An and Anna were created.

Northwest of Orat is the Igo highlands, adjacent to the Draffa mountains, at the corner of Methona that connects the Ubiud Sea to the XXX Ocean. For most of Oratian history, this region was autonomously ruled by Mammonite and Vaninite tribes, occasionally serving Orat in vassalage. By the Venerable Era, the Mammonite and Vaninite identities had largely disappeared as the region was fully annexed into Orat proper.

On the other side of the Draffa Mountains west of Orat is Limnos, a temperate region along the oceanic coast. Limnos is the traditional heartland of the Kalleanite people, along with other Limnean tribes attested in Kallean scriptures. Historically, Limnos was of critical interest to Orat, as it controlled the vital trade rout econnecting them to XXX in the south. While many rulers of Orat's history had the ambition to directly control this region, it typically proved impractical due to the rough terrain, which permitted Limnos and Igo to be historically dominated by small tribal kingdoms and a few powerful city-states. The Dedu River is an iconic feature of Limnos, which forms their northeastern border and runs through the nation into the XXX Ocean.

Dhiss, located just east of the Kera River in Lower Orat, is the largest and most influential city of the region. In some periods of Ancient Oratian history, the kingdom functioned as a single-polity state with all social, political and religious functions revolving around the city of Dhiss. Dhiss was probably constructed in the early Middle Kingdom under Apef the Terrible, who moved from the Old Kingdom capital of Nada located several kilometers west of the Kera. In Upper Orat, Bast is the regional center which probably functioned as a political capital before the Old Kingdom. Bast is located just north of Zoan, the capital of the Zoan Kingdom that was responsible for the Oratian Empire. Ankho, the fifth largest city located in central Orat, served very briefly as the capital during Onan resurgence. Xios is another major city of historical significance, located in Upper Orat and served as the capital of the Sixth Dynasty.

History

The history of Ancient Orat spans over 2,000 years, starting from the beginning of the Nodh Culture in 2300 AA and lasting until the start of the Ruminid Dynasty in 372 AA, which is the start of the Venerable Era. This history is typically divided into six eras, which are distinguished from each other by significant shifts in society, political organization, and material culture: Predynastic (2300-1800 AA), Old Kingdom (1800-1450 AA), Middle Kingdom (1450-1100 AA), New Kingdom (1100-780 AA), Late Kingdom (780-460 AA), and Imperial Era (460-370 AA).

Predynastic

During the Predynastic Era, Orat was politically divided between various city-states that were ruled by separate monarchs. Of these city-states, the archaeological site at Nodh is the largest and most in-tact, from which the period gets its name as the Nodh Culture. Information on this period is scarce due to a lack of written records, but it is believed that they followed a unique polytheistic religion which treated the gods as if they ruled on Earth directly. The fate of the Nodh Culture is unclear, but it is often theorized to have collapsed due to a natural catastrophe, such as a meteor strike or volcanic eruption.

Old Kingdom

The Old Kingdom was founded by the Shada Mino, who unified Upper and Lower Orat around 1800 AA. A unified Oratian culture coalesced within the first few generations of Mino, including a unified law code and standard written language. Mino established the national capital in Nada, where it remained throughout the Old Kingdom. Religion of Orat was unified under the cult of Ona, and administration was disseminated to a hereditary class of feudal nobility. After a succession crisis around 1700 AA, the Shadanate came under the domination of the Ona Priesthood. After a generation of religious rule, the Shada Otis I focused on military expansion, annexing the southern regions of Upper Orat up to the Draffa Mountains. These conquests expanded the power of the nation's mercenary military class, and caused an influx of wealth that strengthened the middle class merchants.

When the First Dynasty died out, the Second Dynasty came to power which was dominated by this same middle class military. This dynasty began to rule in 1640 AA, which is the oldest ruler whose dates are known for certain. During the long reign of Enu II, power shifted again in favor of the hereditary feudal nobility, which caused the nation to suffer from rapid decentralization. This and various other institutional, economic and demographic problems led to the collapse of the Second Dynasty, and the Old Kingdom itself. The Third Dynasty was brief and poorly documented, serving mostly as a transition from the Old to the Middle Kingdoms.

In general, the Old Kingdom is remembered as a kind of ancien regime by Douist historians, back when Orat was run as a typical Bronze Age civilization prior to the introduction of Douism. The Old Kingdom is also known for producing many works of scientific, mathematical, and cultural significance, including innovations of artistic styles that would go unchanged until the Oratian Empire.

Middle Kingdom

After the assassination of Camus the Spider, the Middle Kingdom was established in the middle of the 15th century AA. Early in the Fourth Dynasty, Apef the Terrible made a series of rapid reforms that broke the power of the feudal nobles, and centralized all authority to the central government. He moved the capital from Nada to Dhiss, and abolished both the feudal nobility and the Ona priesthood. While Apef's reforms were a great shock to the nation and led to a high death toll, he is revered by Douist historians for destroying the old system and paving the way for the new Douist society.

Subsequent rulers of the Middle Kingdom would follow up from Apef's reforms to further centralize power to the state. Eventually traditional families and private property were fully abolished, and these institutions were replaced with the Kreena and Miqta systems, respectively. After control of these systems were solidified, the Miqta labor tax became a source of mass mobilization that proved indispensable for military and architectural achievements. The Great Pyramids of Orat were built at this time over multiple generations, as were the series of great aqueducts across the Kera River Valley.

The paranoidal centralization of Orat came at a cost of political stability. When Otis VI was captured in a minor campaign against the Vaninites, this led to a devastating multi-sided civil war known as the War of Five Kings, lasting from 1282-1265 AA. This was the end of the Fourth Dynasty, and the beginning of the Fifth under Kayopis I. The Fifth Dynasty became most famous for their interactions with the Kallean scriptures. The Prophet Yunas first arrived in Orat under Camus III, and the rest of the Kalleanites migrated into the nation under his son Phineas. These peaceful relations did not last long, as the Kalleanites claim to have suffered oppression and slavery under the reign of Coronas II, which is when the Prophet Hobin was born. When Hobin grew older, he led the Kalleanites in a great Exodus out of the nation, causing a wave of destruction and chaos that led to the collapse of the Fifth Dynasty, and the Middle Kingdom with it.

New Kingdom

After the Kalleanite Exodus in 1112 AA, the nation was weakened to the point of splitting into rival dynasties. The south became ruled by the Xioite Kingdom under the Sixth Dynasty, while the north was conquered by a group of foreign nomads known as the Northonans (the Seventh Dynasty). The Northonans did little to displace the Douist society, and in fact made institutional changes that helped facilitate the cultural renaissance of the New Kingdom. After four kings, Orat was reunified by Mikael the Restorer in 1030 AA, who established the Eighth Dynasty in Dhiss.

The Eighth Dynasty saw the apex of Ancient Orat's cultural, political and military influence, particularly during the reigns of Salatis the Magnificent and Roman the Great. It was at this time that Douist philosophy was properly formalized and institutionalized by the writings of Konnu the Wise (c.1060-985 AA), and the Kuraka bureaucracy was also formed. Roman the Great led numerous military campaigns that subjugated most of Orat's sphere of influence, but failed to conquer the Kalleanite Theocracy in Limnos. A generation after these military defeats, Haten III attempted to undermine the influence of the Douist philosophers, and restored the Ona Priesthood, in a period known as the Ona Resurgence (919-893 AA). This period ended with the assassination of Tutti III, which proceeded to abolish the Ona Priesthood once again.

After the Ona Resurgence ended, the next generation saw a great reactionary swing back towards Douism, taking great efforts to purge any semblance of traditionalism out of the nation. Simultaneous to this social upheaval, the New Kingdom in general saw a steep decline through various economic and demographic disasters. It was under this backdrop that various fables from the Oratian Empire takes place, such as The Tale of Arnold the Obsolete Man and The Tale of King Morakai, which were targeted to portray Douist society in a bad light. Morakai was based on a real-life ruler named Morkai, who overthrew the Shada in a popular revolt and established the Ninth Dynasty under his progeny. The rest of the Ninth Dynasty was fairly ignominious, and saw the gradual weakening of the central government in favor of the Kuraka Clans and Douist Philosophers.

Late Kingdom

At the start of the Tenth Dynasty, the nation was effectively decentralized in a period known as the Age of Kurakas (779-730 AA). The last ruler of this dynasty, Sabrina II, proved far more capable than her predecessors, and effectively reunified the nation through her alliance with the Norin Clan. Sabrina has become an iconic figure known as the "Rose of Orat", and her reign saw the rise of a new branch of Douist philosophy known as Feminist Douism.

The Eleventh Dynasty was the longest-lasting in Ancient Orat, but the vast majority of its rulers were fairly weak and ignominious. In 612 AA, a group of Kalleanite exiles led by the Prophet Jesse invaded Orat, settling near the Kera River and forcefully integrating themselves among the people of Upper Orat. In the 6th century AA, the Orat's political and social instability coupled with widespread religious conflict led to the nation being partitioned in half, known as the Divided Monarchy. The Twelfth Dynasty, also called the Zoan Kingdom, was established in 551 AA by Karlos the Liberator, who claimed to be a direct descendent of the Middle Kingdom Prince Norman.

The Zoan Kingdom adopted Kalleanism as its official religion, and many scholars theorize they authored the Kallean scriptures, although this is in dispute. In 484 AA, the Zoan Kingdom forged a personal union with the Skypriot Empire to the east, by securing a marriage between Queen Roxanne the Holy and the Skypriot Emperor Kyro. Their son, Olric II, is considered the first ruler of the Oratian Empire, who conquered the Eleventh Dynasty and re-established the national capital in Dhiss.

Imperial Era

The Oratian Empire proceeded to conquer Limnos along with most of the known world, becoming the largest nation in Methona in its day. This empire was far too overextended and diverse to last for long, and soon it splintered into various successor-states over the next couple of generations. The Ruminid Dynasty assumed power in Orat, and restored Douism as the official religion. The Ruminids lived in a new world defined by the religious and cultural innovations by the Oratian Empire, now known as the Venerable Era. While maintaining traditional Douist beliefs at home, the Ruminids expanded north as a formidable naval power, and dominated the Ubiud Sea until the XXX war in the 2nd century AA.

Religion

Like all other ancient cultures, religion played a critical role in shaping the history of Orat. Originally, Oratian religion evolved organically into a complex polytheistic tradition during the Predynastic period. After the Unification of Upper and Lower Orat, this religion was solidified into a henotheistic system with a unified priesthood, known as the Cult of Ona. During the Middle Kingdom, the priesthood was abolished and the cult of Ona was eroded in favor of the religious and philosophical tradition known as Douism. While Douism remained the official religion from that point well into the Venerable Era, many local religions also persisted among the general population, such as Ona and Kalleanism, typically practiced alongside Douist traditions. On two separate occasions, there were attempts to change the official religion and undermine the power of the Douist philosophers, the first being the Onan Resurgence from 919-893 AA. Under the Oratian Empire (460-372 AA), Kalleanism became the official religion and made concerted efforts to suppress Douism, which were ultimately unsuccessful.

Predynastic Religion

Prior to the Old Kingdom, the Nodh Culture of Orat practiced a polytheistic, shamanistic or possibly animist religious tradition. While this religion seems to have largely died out by the early Old Kingdom, it is historically significant as the point of origin for all subsequent belief systems that appear in Orat, particularly Ona and Douism. The Kalleanite religion arguably retains some influence as well, as the Predynastic gods are referenced in the opening chapters of Kallean scriptures.

The Nodh culture had no written language, which poses some challenge to understanding the Predynastic Oratian religion. However, this is largely made up for by an abundant and dynamic tradition of religious art, which in some respects was comparatively more advanced than art during the later Shadanate. Other gaps of knowledge can be supplemented by a comparative analysis of the mythologies that succeeded them, particularly using sources from the Old Kingdom and early Douist philosophers.

The Predynastic religion was a living mythology, and followed along a consistent narrative that evolved in real-time throughout this era. This religion recognized a large pantheon of gods, depicted either in human form or human-animal hybrid. While the gods are neither omnipotent nor altruistic, their rule over humanity is justified by a vast array of magical powers and dominance over nature. They are described as originating from the Draffa Mountains, having grown out of the World Tree (or Tree of Life). Ona is also believed to have been part of this pantheon, who created An and Anna out of the same World Tree. However, there are no temples dedicated to Ona during this time, and it is theorized that Ona was originally conceived as a god completely disinterested from humanity after having created them.

The Predynastic religion had no concept of heaven or underworld, or any other separate plane of existence. Rather, the gods are always depicted as living with humanity and ruling over them directly. In most depictions, the gods are directing humans how to construct temples, organize agriculture, and dictating laws or other customs. Each individual city-state enjoyed the patronage of a single god, or small group of gods, who would lead that city into battle or diplomacy with deities of other city-states. Beyond that, the exact roles and identities of individual gods are usually unclear.

Predynastic temples were built as mastabas, an architectural tradition that would later evolve into the Great Pyramids. However, on the inside the temple was built to look like a fully-functional palace, complete with an empty throne room, banquet hall, and living quarters for slaves and concubines. It is believed that the throne room was used as an inner sanctuary to offer incense, while the banquet hall was for more common burnt offerings. The mock harem might have functioned as a kind of temple prostitution, but this theory is less supported.

Local rulers during the predynastic era would justify their rule as being directly related to these deities. Many religious inscriptions describe these kings as being the son of some god or goddess, and entering some pact with them to be granted supernatural powers in exchange for worship. The class of demigods that descend from the original pantheon maintain their own special status in the religion, halfway between the full-bred gods and humanity. Many of these demigods, however, are depicted solely as wild animals or other-worldly monsters, possibly to represent the loss of their humanity altogether.

Ona Cult

At the very beginning of the Old Kingdom, a cult religion centered around the god Ona first appeared in the city of Bast. After Orat was fully unified under Mino I, the Ona cult quickly spread to fully supplant the predynastic religion over the whole kingdom. Ona was a henotheistic religion, centered around an all-powerful creator god while acknowledging the existence of many lesser deities. These lesser gods varied between benevolent servants of Ona and malevolent spirits.

While the predynastic religion had a loose shamanistic tradition, the Ona cult had a fully-organized priesthood arranged in multiple levels. At the highest level, the Chief Priest of Nada held absolute authority over the religion, matched only by the Oratian monarch. Just like in the predynastic religion, the Ona temples were made as mastabas. However, the inside was drastically more simple, consisting of a single shrine for burnt offerings and various smaller shrines for good and evil spirits. At the height of their influence, the Ona priesthood was also known to create one of the world's earliest education systems, organized out of the Great Temple of Nada. Some of the most influential scholars of the Old Kingdom, such as Motepi, were also priests of Ona.

Political influence of the Ona priesthood varied considerably throughout the Old Kingdom. At its apex during the minority rule of Tutti II, the Chief Priest of Nada held nearly de-facto power over the entire nation. This power gradually eroded over time, being undermined by secular feudal nobles, until the priesthood was fully abolished in the early Middle Kingdom by Apef the Terrible.

It is uncertain what happened to the Ona cult after that point, and whether the religion ever truly died out prior to the resurgence under Haten III. It is commonly theorized that the Ona religion continued as a private, if not secretive tradition after the priesthood was abolished, practiced either alongside or in place of the Douist ancestral veneration. Douist historians maintain this must have been a small minority, as the Ona religion relied solely on the priesthood in the Old Kingdom and had no private rituals. Thus, any private practices that appeared before the reign of Haten III must have been organically developed over a long period of time.

It is generally believed that the original Ona religion during the Old Kingdom was fairly simplistic, relying only on unscheduled burnt offerings conducted at local temples, and had no solid orthodoxy. During the reign of Haten III in the late New Kingdom (919-901 AA), the Ona priesthood was re-instated as an attempt to subvert the power of the Douist philosophers. During this period, the doctrines of Ona were greatly fleshed out, and the religion was much more complex and nuanced than in the Old Kingdom. These doctrines are largely inferred from the Hatenian Hymns, as well as contemporary Douist and Kallean sources, for all other writings from this period were ultimately destroyed.

According to those sources, Ona was a benevolent god who offered immortality to his followers in exchange for acts of piety. These acts come in the form of regular burnt offerings, consisting of either animals, vegetables or incense, and conducted either at a private shrine or public temple. The Hatenian Hymns also emphasize the omnipotence of Ona, describing his supreme authority over all other celestial beings. It is highly debated whether these descriptions are a literal transcendent God in a monotheistic sense, or merely a metaphor for his traditional authoritarian role. The relationship between this Ona resurgence and the contemporary Kalleanites are part of the greater Doutang debates.

After Haten III's reign, the Ona religion disappeared from the record once again. According to some late Venerable sources, the last Ona followers survived into the Oratian Empire before converting to Kalleanism.

Douism

Douism is a non-theistic, philosophical and religious tradition that dominated in Orat for most of its ancient history, and had an unparalleled impact on their social, economic and political development. It originated as various loose traditions in the early Middle Kingdom, which were later unified into a formalized belief system at the height of the New Kingdom. While Douism does not claim any single founder, much of its formalization is attributed to the writings of Konnu the Wise (c.1060-985 AA). Today, Douism is practiced by 8 million people worldwide, making up 10% of Orat's population.

Douism is based around the Dou, a philosophical concept that encompasses the inherent order and balance of the universe. The Dou is divided into three separate forms: the Cosmic Dou, the Social Dou (also called Sagwe), and the Personal Dou (also called Kaba). The Cosmic Dou constitutes the balance of forces in the natural world, ranging from stars and planets all the way down to plants and insects. The Social Dou describes the balance of social and political forces between people, such as laws, governments or economic systems. The personal Dou, or Kaba, describes the metaphysical order that defines an individual human body. The Kaba is sometimes considered the equivalent of a soul in Douism; however, the association is an oversimplification, and Douist philosophers maintain that they deny the existence of souls. Rather, the Kaba is a kind of blueprint of how the body is put together, and the collective of atoms that constitutes its mass.

Not all Kabas are the same, and can be arranged in a hierarchy that reflects their relative positions in the Social and Cosmic Dou. This system is called Kabanistic Hierarchy, in which individuals who contribute the most labor to society are ranked higher than those who contribute less. The Shada, at the very top of this system, is the closest equivalent Douism has to a kind of deity, where the monarch's secular political power is inseparable from his divine authority. Consequently, blind obedience to the state and political authority is the highest form of virtue in Douism.

Douism believes that when the human body dies, the Kaba remains in-tact and is absorbed back into the Cosmic Dou. When a new human is born, the atoms of their body is drawn from the Kaba of a previously-deceased human, which is essentially the Douist concept of reincarnation. Trapped in a self-perpetuating, cosmic cycle of life, the Kaba is cursed to be reincarnated in a world full of misery, death and suffering. The only means of salvation in Douism is for the individual to reach their peak potential in the Kabanistic Hierarchy, as well as an enlightened understanding of the Cosmic Dou. Once this is achieved, the Kaba may be released from reincarnation and fully snuffed out of the universe.

Douist shrines and ritual practices involve a kind of ancestral veneration, meditating on deceased individuals who are currently one with the Cosmic Dou. Douism has no clergy or organized structure, but instead is led by an elite class of eminent philosophers. These philosophers come from multiple schools of thought, most of which traces their origin to the disciples of Konnu the Wise. Douism values innovation and scientific progress, but it is only permitted it if it can be used to reinforce the values of Douist philosophy.

Douism values collectivism and the elimination of private property. They believe that any attempt to assert individualism or individual identity is inherently selfish and greedy, and thus the highest possible offense against the Dou. Consequently, redistribution of wealth is a critical part of the Social Dou, and any social institution outside of the state must be abolished. These institutions considered to be a threat to the Social Dou (including feudalism, organized religion, and traditional families) are associated with "barbarian" peoples outside of Orat. Claims over private wealth, or even biological children, are considered equally unethical.

Organized religion, and any similar assertion of a moral standard outside of the Social Dou, is also considered an evil practice. Douism values hedonism, and teaches that any basic impulse or desire is ultimately good, as long as such desires aren't a threat to the Social Dou. Likewise, it is morally wrong to deny a person something that fulfills his needs, as that is asserting individualism and private property.

It is the ultimate goal of Douism, and the national identity of Ancient Orat, is to liberate all peoples of the world by subverting and eliminating these barbaric, individualist institutions, and absorb all nations to become one with the Dou. Doutang, often translated as "skepticism", is a system where Douist philosophers subvert and attack foreign religions through a series of formalized debates and homilies.

Kalleanism

Kalleanism is a monotheistic, traditional and semi-evangelical religion central to the culture and history of the Kalleanite People. The Kalleanites were originally a tribal kingdom that came to dominate the region of Limnos, and had a strong influence on Oratian history through trade and warfare. The Kingdom of Zoan in Upper Orat, established in 551 AA, adopted Kalleanism as its official religion. Likewise the Oratian Empire in 460 AA spread Kalleanism over the entire nation. Although Kallean influence in Orat disintegrated after 370 AA, it still made a lasting impact in many ways, and eventually evolved into the Melchian faith after the Axiomatic Revolution. Today, there are approximately 20 million adherents of Kalleanism around the world, of which about 1-2 million live in Orat.

The origins of Kalleanism are considerably controversial. According to Kallean scriptures, the Kalleanites originated as the descendants of the patriarch Limnos, who was first called to be a Prophet of God around 1280 AA. The earliest texts of the Kallean scriptures are attributed to the Prophet Hobin, who was responsible for leading the Kalleanite Exodus in 1112 AA. Archaeology and contemporary historical records verify the long history of the Kalleanites. However, it is not agreed upon exactly when during their history that the Kallean religion first appeared, nor is it known when the Kallean scriptures were written. The most conservative estimate, perpetuated by the majority of Orat's academic elite, is that the Kallean religion was first created by the Zoan Kingdom in the 6th century AA, in opposition to the Douists in the north. After the Oratian Empire conquered Limnos in 449 AA, the religion became retroactively associated with the Kalleanite people. This narrative, however, is rejected by both Kallean and Melchian scholars, who instead uphold the traditional narrative of Kallean scriptures. It is, understandably, an important topic in the Doutang debates.

Doctrines and practices of Kalleanism are eloquently spelled out in the Kallean scriptures, consisting of 21 canonical books and an uncertain number of apocrypha. The religion adheres strictly to a single, omnipotent and transcendent God who is not only benevolent, but passionately cherishes the humanity he created. The name for God is typically rendered as Shwowr in Kallean scriptures, which simply translates to "The Only God", in addition to various other poetic titles. Kalleanism recognizes the existence of good and evil spirits, somewhat similar to Ona, but Kallean spirits are particularly finite and on par with humanity, which doesn't compare to the infinite nature of God.

God created An and Anna out of the Tree of Life in the Draffa Mountains, the first man and woman. According to Kalleanism, all humans have a non-physical soul which is a unique and special creation by God, and places humanity on a superior level above the natural world. Kalleanism also believes in a celestial afterlife, and that human souls that achieve salvation lives in the presence of God forever. Having placed humanity in this position of authority, God has a vested interest in providing people the key for an eternal and prosperous life. To that end, God provided humanity with a set of laws and rituals, most of which is described in the Hobinnical Law code in the Kallean scriptures. By adhering to these laws and rituals, each individual ensures a happy life in the physical world along with eternal salvation. Humanity is given a choice, one being a path of life that requires obedience to God, and the other being a path of human will that leads to its own destruction.

The Hobinnical laws in Kallean scriptures usually revolves around love and respect for all people, particularly the poor and needy. It enforces traditional family roles, that obligates parents to provide for and instruct their children. It requires a modest lifestyle that takes careful moderation in all things, keeping base impulses in check. Individualism, which reinforces the divinely-created soul, is considered the highest form of virtue, and a person's consent is required before taking anything from them. Kallean scriptures essentially support a theocratic government, where the secular state purely exists to protect and enforce the will of the church and family.

Kallean rituals are conducted at a single temple, the Great Temple of Kalla. It is here that the Kallean priesthood makes burnt offerings to God at various specific times of year, which is used to cleanse the nation of sin for that season. There are no private shrines, but instead the people gather in public places for ritual prayers and hymns conducted by a priest. According to Kallean scriptures, the Prophet used to have a significant role in the religion back when the Kalleanites lived in a theocracy. However, after the Oratian Empire the role of Prophet has been eternally vacant, leaving the High Priest of Kalla as the highest religious office.

While the Kallean religion is normally associated with the traditional practices of the Kalleanites, it is not an ethnically-based faith, and any nation willing to follow the Hobbincal Laws are permitted to convert.

Art and Architecture

Art of Ancient Orat encompasses various works of reliefs, painted pottery, and sculptures that were produced from the Predynastic period onward. Orat was also known for large-scale works of architecture and engineering, such as the Great Pyramids which are one of the Great Wonders of the ancient world. Literature was also known as one of Orat's high arts, including works of both fiction and non-fiction from either novelists or Douist philosophers.

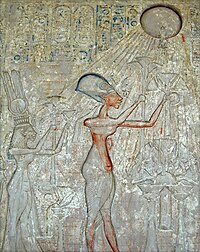

In the Predynastic Era, art was made purely for religious purpose. The mastaba temples to the Predynastic gods were furnished and decorated as a fully-functional palace, a unique style of architecture not seen in later eras. Painted reliefs and steles were used to document their living mythology, and the constantly-evolving relationship between the gods and humanity. The gods and demigods always took center stage in Predynastic art, with human rulers given a minor role. In terms of style, Predynastic art was two dimensional with no consistent perspective, showing characters as idealized and symmetric. Still, it introduced important concepts not seen in prehistory, such as hierarchy of scale a consistent ground line. In terms of architecture, the Predynastic period was fairly rudimentary, focused mainly on city walls and defenses.

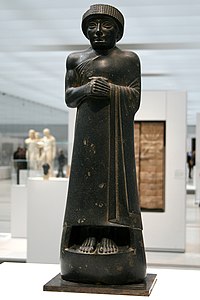

In the Old Kingdom, art was used equally for religious and monumental works. The Ona temples were much smaller and simpler compared to the Predynastic period, and the amount of religious art was heavily reduced and simplified. Rather than showing a constantly-evolving narrative, the Old Kingdom settled on a consistent formula to depict Ona's relationship with the current Shada, and repeated this same formula for most of this period. However, the Old Kingdom also introduced secular monumental art that celebrated great moments in the Shada's reign, such as a pivotal battle or new code of law.

These works of art would typically depict the symbol of Ona in the background, with an image of the Shada at the center. While Old Kingdom art was reduced in scale, it did make attempts to innovate and experiment with style. Some painted reliefs of the Old Kingdom were murals depicting a slice of Oratian life, and made attempts at depicting motion from birds or horses. There were also some experiments with perspective, most famously seen in the Harvester's Vase. In terms of architecture, the Old Kingdom pioneered great works of engineering such as levies and canals that controlled the flow of the Kera River. Motepi is often attributed for these innovations, but it's likely he simply participated in a greater scientific movement.

The Middle Kingdom was the apex of architectural engineering, taking full advantage of the mass labor force provided by the Miqta system. The Great Pyramids of Orat were conceived as stacking multiple mastabas on top of each other, and functioned as a tomb for Apef the Terrible and the rest of his dynasty. It is often believed that the Great Pyramids was a monument to Douism, as the pyramidal shape is the most iconic symbol for the Douist religion. However, it is more likely to be the other way around, that the pyramidal shape was adopted by later Douist philosophers in memory of a perceived golden age started by Apef the Terrible. The pyramids are not the only monumental work from the Middle Kingdom, however. The large-scale works of engineering used to irrigate the Kera River valley also drastically increased in size, further making use of the Miqta labor tax. The Great Aqueduct of Kedah is likely not the only aqueduct created in the Middle Kingdom, even though it is the only one to survive to the present.

After the dissolution of the Ona priesthood, art in Orat was almost entirely monumental in use. As Douism rose to greater prominence, the primary function of art was a propaganda tool in favor of the secular state, particularly the Shada. It was also critically important that art was used to reinforce beliefs of Douism and norms of the Social Dou. To this end, there was a severe censorship of art to purge any work perceived to be a threat to the Dou. Archaeology has found waste pits containing defaced or vandalized works of art, likely as a result of this policy. Typically, these lost works give favorable depictions of non-Douist cultures, such as traditional families or feudalism.

For much of Oratian history after this period, art severely stagnated with very little change. Many works from the New and Late kingdoms are mirror images of that from earlier periods, but substituting characters from one time period from another. There was also a slow decline in craftmanship, losing all of the innovations from the Old Kingdom and going even further backwards in some cases. For example, there was a complete loss of perspective and inconsistent use of ground lines. There are several theories why Oratian art went through this phase of stagnation. First, the Douist censorship of the arts incentivized artists to not be too experimental, and preferred to copy earlier works that already had government approval. Second, the lack of any internal markets meant there was no internal competition between different artists, removing a major incentive for innovation. Third, the Qayyan Principle often meant that an artist would neither enjoy his own craft, nor would he be compensated for making it, thus removing any incentive to maintain a high quality.

Literature

Writing was invented at the very beginning of the Old Kingdom, using a combined logographic and syllabic system now known as Oratian Hieroglyphics. It is largely considered to be one of the oldest writing systems in the world. During the Old and Middle Kingdoms, much of the historic information we have on Ancient Orat comes in the form of monumental or religious inscriptions, detailing a religious ceremony or single historical event. The Old Kingdom also had a rich tradition of scientific and mathematical works, most famously from the polymath Motepi.

Ancient Oratian literature reached its peak during the New Kingdom, specifically the "Golden Age" of Douist philosophy during the time of Konnu the Wise and his disciples. While philosophical literature dominates the surviving corpus from this era, there are also traditions for writing fables and short stories from this era. The New Kingdom also had a tradition of writing collections of poetry, such as the Hatenian Hymns from the Ona restoration period. While literature slightly declined in the Late Kingdom, Douist philosophical and scientific writings continued, including a collection of proverbs by Shada Roman V. Douist literature included works of natural science and astrology, and historical essays on the reigns of recent Shadas. It is likely that Orat also had official chronicles and legal documents, but these have been almost entirely lost.

Just like with art traditions, Douist philosophers had a strict censorship of literature, such that publishing any work perceived as a threat to the Dou could be accused of treason. As Douism became more extremist in the later New Kingdom and early Late Kingdom, this censorship began to condemn classic works from earlier in Oratian history, even from other Douist philosophers. The philosopher Fusci (c.880 AA), who condemned the writings of Motepi, famously stated "one may pose themselves as a philosopher in order to avert suspicion of their treason". It was also a Douist tradition to constantly revise their view of history to best align with the current Social Dou (that is, in favor of the current political regime). This often poses a challenge to historians, as sources from two different generations are often contradictory to each other.

During the Oratian Empire, these Douist essays began to coalesce into a systematic investigation of history. Gallo of Kedah, the "Father of History", cites various historians as sources from this period, all of which are now lost.

Economy

Agriculture is the backbone of the Oratian economy. Lower Orat near the Kera delta is the breadbasket of North Methona, including the staple crops of corn, squash, and cocoa beans. Upper Orat near the Draffa Mountains is best known for its mining industry, alongside some agriculture as well. The materials most often produced from Upper Orat consist of gold, silver, copper, and zinc. Obsidian is also sometimes produced from this region in smaller quantities. In terms of protein, cows and sheep are raised in Lower Orat, in addition to a thriving fishing industry along the coast. Orat also produced manufactured goods that would also be exported abroad. This included textiles made from leather and wool, metalworks made from bronze or obsidian, and pottery made from painted ceramic. The craftmanship of these products reached an apex during the Old and Middle Kingdoms, and slowly declined for the rest of Oratian history.

Very early on in Oratian history, the Old Kingdom constructed a series of levies and canals to fully utilize the tributaries of the Kera River. This complex system of mass irrigation is considered an engineering marvel of the ancient world. These waterways were also heavily utilized as a means of transportation, and Oratians would use large paddle boats and barges to quickly move logistics and military anywhere in the nation. An actual efficient road system was never needed until the Oratian Empire, when the nation's borders stretched too far beyond the Kera.

Wealth of Orat came from international trade. The most critical trade route for Orat wrapped north around the Draffa Mountains, then south through the Limnean region along the coast down to the land of "Punat", which modern historians now know was XXX. This trade route supplied Orat with tin, as well as various spices and incense, which they would spend large amounts of gold and silver to obtain. The treacherous journey around the Draffa Mountains, dominated by various tribal nations like the Kalleanites, contributed to making these products so valuable. Orat exported their minerals and agricultural products abroad, mostly to nomadic people living in the Skypriot plains. To the north, Orat never sustained trade (or even contact) beyond the Ubiud Sea until the Ruminid Dynasty.

Ancient Orat had no concept of standard currency. When making trade with foreign nations, it relied on gold and silver bullion only, typically subdivided into a standard system of weight called shekels. However, this was a very different situation for the internal economy of the nation. Orat had no concept of an internal market system, nor did they have any kind of mercantile class or capitalism. It is also argued that Orat had no concept of privately-owned wealth, but this point is a bit more complicated.

Miqta System

Ancient Orat relied on a process of mass conscripted labor called the Miqta system. Based on the Douist beliefs of collectivism and contribution to the community, every citizen of the nation was required to participate in this organized unpaid service to the state, often referred to as a labor tax. Most of the time, the labor tax consisted either of farming or construction work such as bridges or canals. All food produced by Oratian farmers are collectivized by the government, and stored in a local warehouse called a Qello. This same collectivization can apply to almost any product by the Miqta system, such as through mining, manufacturing, and even art, according to the Douist belief that everything in the state belonged to the Shada. The Miqta system was organized into units of 10,000 people or less, and applied to both men and women between the ages of 20 and 60 years old. These Miqta units could also double as a peasant militia, which was the backbone of the Oratian military.

In return for the labor tax, every citizen of Orat is distributed food, housing and other necessities in set amounts that are prescribed by the state. The size and privileges of this redistribution was directly proportional to the Kabanistic Hierarchy. This not only meant that people of higher social status were given larger portions of food and land of higher quality, but also gave them greater control over what kinds of consumer products they could access. Thus, it was normally the case that works of art produced by the Miqta system would be confiscated and distributed among the Kurakas and other social elite. Participation in the Miqta system was involuntary, and harsh penalties were prescribed to those who failed to contribute their expected quota, up to and including death (as in the Day of Undesirables).

Douist philosophy taught that redistribution of wealth should be a "monarchy of the workers". That is, citizens who contribute more to the community through the Miqta system should be rewarded with higher status in the Kabanistic hierarchy. Archaeology suggests that this was often true at the local level, and many city governors started their career as common laborers or farmers. Opportunities for promotion were also more fair in the military, and most field officers were usually promoted from common soldiers. Across the society as a whole, however, there was a drastic gap in power between commoners and the elite, and higher government offices were monopolized by the Kuraka clans and Douist philosophers. During the Oratian Empire, Armand the Great started the process of phasing out of the Miqta system entirely, working to replace it with a system of volunteer, paid professionals. These attempts at reforms, however, died with the rest of the empire.

Due to these factors, it is often debated by historians whether Orat is charactarized as a slave society. Douist philosophers and the majority of academic elite disagrees with the label, and asserts that Orat abolished slavery with the introduction of Douism. However, a significant number of historians do characterize the Miqta system as a form of slave labor, despite many differences between the two systems. Not only was the Miqta system a kind of unpaid forced labor, but Oratian society as a whole treated its citizens as property that could be confiscated and redistributed (such as the Kreena). Douists rebuttal that Orat did not have slavery because they did not have any slave markets, either internally or internationally, where people could be captured and sold like other ancient societies did. And while the labor tax wasn't compensated monetarily, it did receive a social reciprocity in the form of promotions and wealth distributions. The question continues to intersect with the Doutang debates.

Sources are contradictory on how much Orat held a concept of privately-owned possessions. Most sources suggest that there was a difference between wealth (food, land, precious metals, etc.) verses small personal possessions. These sources also imply that the former (personal wealth) could not be owned privately, but could be confiscated by either the government or other citizens under the Qayyan Principle. However, the latter (small personal possessions) was privately owned, and attempting to take them would constitute criminal theft. However, there is a contradiction as many anecdotes describe personal possessions being confiscated, and nothing being done about it. Three theories are proposed to explain this: 1) That the definition of "personal possessions" is more narrow than in modern society, 2) that the definition changed throughout Oratian history, or 3) that the laws against theft were simply ignored, as Orat had no means of prosecuting government officials.

Administration

Most of Ancient Oratian politics, society and religion revolved around the Shada, holding the highest level responsibility at the very top of the Kabanistic Hierarchy. The Shada was an absolute, all-powerful role that had total authority over every aspect of the nation, which was all treated as his direct personal possession. An alternate title for the Shada was sometimes called "The Man of Orat", which reflects the belief that the monarch is the living embodiment of the Oratian community, and therefore the only truly individual human being. The name Shada literally translates to "living god", which was probably inherited from the Predynastic tradition of royal demigods. The title was still used after the rise of Douism, although the religion has no concept of a god or demigods, based on the idea that the Shada is the closest to divinity a person can possibly be. The Shadanate had a single crown, which was passed on from one ruler to the next, and this tradition reportedly continued from King Mino all the way through the Ruminid Dynasty.

The royal family was exempt from the Kreena, and the Shada's children would be tutored at the royal palace at Dhiss by Douist philosophers. The Shada did not have an automatic line of succession, but needed to designate an heir apparent. It was believed that the most stable arrangement for the monarchy was to have only one possible heir at a time, as said by Konnu the Wise "one to hold power, and one to crave it". In order to ensure this was the case, it was not uncommon for the Shada to assassinate members of his family or give them up to the Day of Undesirables. In the Old Kingdom, it was customary for the Queen mother to rule as regent in the event their son was in minority or mentally unfit. In the erosion of family structures with the rise of Douism, this policy fell out of favor.

In the Old Kingdom, the role of Shada was not absolute, and the state was administrated by hereditary feudal nobles who had control over their own titles and armies. After the rise of Douism, feudalism was abolished and replaced by a complex bureaucracy of appointed ministers, magistrates and governors. The Shada had the power to redefine, re-arrange, or even dissolve these offices at any time. This bureaucracy aligned with the strict social stratification of Kabanistic Hierarchy from Douism. In theory, this system was meritocratic: if a minister displayed exemplary performance in his current role, then he would graduate to a higher level of the social strata.

In reality, the ministries eventually became rife with nepotism, as each minister would ensure high-ranking offices for their family members. By the Late Kingdom, power had become concentrated around various political dynasties, sometimes called the Kuraka clans. These clans would use their political influence to secure higher privileges and better standards of living for themselves and their allies, at the expense of the rest of the population.

That being said, not all offices were controlled by the Kuraka clans. Ordinarily, the Shada would look to the military to find individuals of outstanding performance in the service of his country, and promote them to government positions. As the Miqta system of military conscripted from the general population, then it was theoretically possible for anyone to climb the social ladder through military service. Many Shadas would use these kind of promotions as a way to counterbalance the power of the Kuraka clans. During the Oratian Empire, the same system of administration was maintained, but the Kuraka clans were forcefully deposed from power completely.

Douist philosophers also held significant political influence, as everyone respected their knowledge of the ideal social and cosmic order. It was rather common for Douist philosophers to be granted high-ranking ministry positions, and hold royal privileges comparable with the Kuraka clans. Most of the time, the Douist philosophers were closely allied with the Kuraka clans, and helped to support each others position in opposition to the king. It was for this reason that many reformers such as Hattin III tried to undermine the Douists' power.

The highest appointed office of the kingdom was the Viceroy, sometimes anachronistically called the "Junior Shada". The Viceroy supported the king in making decisions on legislations, and held effective power over the state in the king's absence. Typically, the title of Viceroy would be given to the current heir apparent, such as the king's son, but there were many occasions when these two roles were separate. The Viceroy was a convenient way of ensuring continuity of government, as he could take power if the king unexpectedly died. After the Viceroy, the next highest-ranking title was the Apu. The Apu represented the king in each hemisphere of the nation, so he did not have to be everywhere at once. Typically, there would be two Apus: one in Upper Orat and one in Lower Orat. During the height of the New Kingdom under Shada Roman II, a third Apu was appointed for the lands east of the Draffa Mountains.

Under the Apus, the nation was divided into dozens of local governates ruled over by an appointed Kuraka. It was this level of office that the Kuraka clans typically held power. Unlike the Apu, the Kuraka did not have authority to lead military themselves. Instead, he would be allotted a personal guard of a few hundred soldiers, used to protect his immediate family and personal estates. During the Late Kingdom, these guards were greatly expanded, granting the Kurakas full armies at their disposal. Under a Kuraka, local city governors also existed to maintain law and order of individual communities, who would typically be given a single garrison. The city of Dhiss has no Kuraka, but is directly ruled by the Shada as a kind of city-state within the nation.

Military

The military of Orat was intimately tied to the Miqta labor tax. The very same Miqta units who were conscripted for mass labor can also be levied during military campaigns, essentially becoming a popular militia. The vast majority of the army were infantry, but soldiers with longer military careers can be promoted to chariot-based archers. Most soldiers were trained with spears and slings, and were given leather armor with iron shields for protection. More elite units had bronze armor with a kopesh sword or bolas. Military officers could only be appointed by the Apu or Shada, who could otherwise lead the army themselves. The Shada also commanded a navy of river barges that controlled the waterways branching from the Kera River, but no navy was ported to the Ubiud sea until the Ruminid Dynasty.

In total, the Oratian army was 100,000 soldiers at its largest extent, divided into Miqta units of 10,000 people each. The greatest strength of the Oratian army was overwhelming numbers, able to quickly raise and deploy vast conscriptions for decisive campaigns. When it came to military technology and tactics, Orat severely stagnated after the end of the Old Kingdom, and their discipline remained virtually unchanged down to the very end of the Late Kingdom. The military started making significant reforms in the last years before the Oratian empire, and was completely overhauled during the Imperial Era and Ruminid Dynasty.

Law Codes

Archaeologists have never found a complete law code of Ancient Orat, but some information about their legal system has been reconstructed based on fragments and anecdotes. Local city governors would organize a local garrison of military for maintaining law and order. Ancient Orat had no concept of civil courts, and consequently their jurisprudence was relatively simple. Instead of a court system, sources describe people being accused of crimes by public acclamation by their neighbors. If the acclamation was persistent enough, or the accused crime in question was particularly severe, then the city governor would dispatch the garrison to carry out justice immediately without due process. If the crime was fairly minor, or the acclamations were contradictory, then it seems that the governor will simply ignore the crime altogether. There is also evidence to suggest that the law codes of Orat never lasted particularly long, but were frequently changed or recreated at the whim of each Shada.

Major crimes in Ancient Orat was anything that was a threat to the Social Dou, such as an act of insurrection or civil disobedience. Spreading teachings contrary to Douism, even implicitly, could also be considered a major crime. Minor crimes were anything that affected an individual person or personal possessions, which did not have an impact on the state or greater social order. It seems likely that rape and theft were considered illegal, although they were rarely enforced as they were considered minor crimes. Murder, however, was considered a major crime, outside of state-sanctioned incidents like infanticide or the Day of Undesirables.

Society

Much of Ancient Oratian society was shaped by the principles of Douism, and a belief that the Social Dou of Orat was the most ideal social order of the human race. Oratians were deeply xeonophobic, and regarded any foreign people and foreign cultures as inferior "barbarians". While this kind of xenophobia was common for most ancient cultures, for Orat this was an official state policy, as the tenants of Douism is inherently superior to the institutions of nations that Orat would typically encounter (such as feudalism, tribalism, organized religions, and traditional families). For a similar reason, Oratian society became noticeably stagnate after the Middle Kingdom, with barely any fundamental changes prior to the 5th century AA. According to the Douist philosopher Urco (fl. c.890 AA), the Social Dou was the "terminal end of history", and any further attempts to change society is automatically a threat to the Dou. The fable of King Morakai reflects how this stagnation was perceived by later writers.

Ancient Oratian society was quite nihilistic, and believed in maximizing material pleasure out of life before their inevitable death and reincarnation. This manifested in hedonistic, self-indulgent practices encouraged by the tenants of Douism, up to and including gratuitous use of sex, alcohol and narcotics. In many cases, indulging these carnal desires was used as a justification for the Qayyan Principle, since it counted as a kind of "need".

Social Hierarchy

For most of Ancient Oratian history, power was closely concentrated around the Shadanate, giving the monarch absolute authority over every aspect of people's lives. Following the Douist belief of wealth redistribution, the personal estates at every level of society was prescribed by the federal government, replacing the need for feudal titles. However, this redistribution was not equal, but instead was weighted by the person's role in society based on the Kabanistic Hierarchy; that is to say, higher government and military offices were given more lavish estates while common laborers and farmers were given minimal accommodations within the Miqta system.

Effectively, Ancient Orat had a very restrictive social hierarchy, as the wealthier Kuraka officials would distance themselves from the poorer Miqta laborers, and the Kabanistic hierarchy of Douism only served to reinforce this norm. In a major metropolitan such as Dhiss, the larger Kuraka estates would be located in the city center, pushing the Miqta laborers and farmers to the suburbs and countryside. There were also more complex levels of society besides these two, such as multiple levels of Kurakas and multiple levels of Miqta.

Due to a lack of private property, the Shadanate reserved the right to confiscate and redistribute personal possessions from anyone in the kingdom, and he could defer this right to high-ranking officials acting on behalf of the government. This technically could apply to any level of society, and on rare occasions a Shada strong and competent enough would dissolve the power of high-ranking Kurakas and redistribute their wealth to lower offices. However, most of the time the political influence of the Kuraka clans were deeply entrenched, so the right of property confiscation was only used against Miqta laborers.

That being said, the Shada was not the only person to have this kind of privilege. Konnu the Wise famously wrote "the poor should take from the rich man's table". In other words, each person has the right to appropriate possessions from a wealthier individual without consent, according to their needs. This was known as the Qayyan ("borrowing") Principle, and while this was the idea in theory, effectively Orat became rampant with muggings and burglary, making long-distance travel a dangerous affair. Because the Qayyan Principle was considered part of the Social Dou, it was often the case that attempting to stop a mugging was considered a worse offense than the mugging itself. Also, while this technically applied to every level of society, the reality was that the wealthier Kurakas would deploy their personal military to keep their possessions secured, but instead used the Qayyan Principle to justify confiscating of property from the lower classes.

Child Rearing

While Ancient Oratians understood the concept of traditional families, by and large it was considered morally abhorrent. The very idea of children being raised by anyone outside of the state was believed to be unethical at best, if not an act of social insurrection. Instead, newborn children past the age of six months were required to be donated to a central government-controlled community center, called the Kreena (literally, "child pit"). This requirement was considered an extension of the Miqta labor tax, often referred to as the "child tax". The Kreena was designed to align all new citizens to the tenants of Douism, and any attempt to resist the child tax is automatically assumed to be working in opposition to the Dou.

While the child tax was required for all children over six months old, women were allowed to donate infants younger than that, which would be given to a designated wet nurse until they were weened. In early years of development, the infant would be put into a collective daycare arranged in vault-like rooms, cared for by a staff of nurses. Starting at the age of three, the child would begin basic training and education, commonly referred to as a Kree-Miqta. Some sources claim that the Kreena was the world's oldest mandatory public education system, but this is a bit of an overstatement. The Kree-Miqta was primarily used to instill obedience to authority, a motivation for productive and efficient work, and other fundamental aspects of the Social Dou. In rare occasions, some Kurakas were known to employ the Kree-Miqta for actual work, typically as basic household jobs like a staff of servants. Some anecdotes claim that it was a common practice to introduce and educate young children on hedonistic pastimes that were encouraged under Douism, namely sex and alcohol. This would be typically between the ages of 6-8 years old.

At the age of twelve, the child graduates from the Kreena and is given more formal training from a local guild. This training would be specialized to the role in society the student qualifies for, based on their performance in the Kree-Miqta. This guild training had no set limit, but typically lasted between six to ten years. The vast majority of children in the Kreena would end up becoming either farmers or manual laborers, while others would become a more specialized job such as artisans or tradesmen. Those with a particularly excellent performance may end up being household servants or secretaries of government offices. It was extremely rare, if not impossible, for anyone in the Kreena to directly graduate as a government minister or philosopher, as these roles were much too high in the Kabanistic Hierarchy.

The scale of how much the Kreena was used is not fully agreed upon, but there is much study on this topic. The Kreena was not a single location, although the center in Dhiss was by far the largest. Each local community would have their own Kreena facility, and major cities may have up up to a dozen. In total, there are 187 Kreena facilities across the nation that have been identified by archaeologists, and possibly many more have yet to be found. Each facility had a maximum capacity between 10,000-50,000, containing hundreds of vaults that could support about a hundred infants at a time. Living conditions of this facility are not known, but archeology suggests that the mortality rate in the Kreena was slightly higher than that of other ancient civilizations. Currently, the archaeological sites of the Kreena facilities are off-limits to the public and can only be accessed by the academic elite of Orat.

In theory, the child tax applied to every citizen in the nation, but this was not always the case in practice. Influential Kuraka clans would be waived from this responsibility, and appoint Douist philosophers tutor their children at home. This is possibly the chief reason why Kuraka clans still operated as family units while most of the population did not. Also, primary sources mention local military routinely being deployed to enforce the child tax, suggesting that resistance from attempted parents was fairly common. During the Late Kingdom, some Douist philosophers lamented that the unethical practice of parenthood was rampant across the nation. This is also an important point in the Kallean scriptures, which describes how the Kalleanites avoided the child tax around the time the Prophet Hobin was born.

Infanticide was also a practice that was morally acceptable in Ancient Orat, and considered a reasonable alternative to paying the child tax. As was the case with most ancient civilizations, it is theorized that this was encouraged as a form of population control. This practice was also protected under the Social Dou, so attempting to stop a mother from committing infanticide was usually considered immoral.

Marriage and sex

Ancient Orat had a rather unique attitude towards sex. The closest equivalent of marriage in Ancient Oratian society was the erot agreement. Erot is neither a religious nor secular institution, but is rather an informal agreement for sexual partners to cohabitate, which can apply to any number of individuals of any gender. Attitude towards sex is extremely lax and desensitized, and no form of sexual activity is ever considered taboo, either public or private. In essence, being in heat is considered a normal bodily sensation just as much as hunger or fatigue is. Across the history of Ancient Orat, examples can be found in primary sources of polygamy and polyandry, bestiality and pedophilia, although usually not in the same time period.

As a consequence, Ancient Orat considered sexual assault as a fairly minor offense. In the absence of individualism and private property, this also applies to private control over ones own body, as their body ultimately belongs to the community. Thus, sexual assault can often be permitted under the Qayyan Principle. If a man or woman is in heat, it is immoral to deny them release, just the same as it would be immoral to not gratify their hunger or thirst. In other words, a person's erotic capital was another form of wealth that must be redistributed to the community. A naturally-atractive person wearing overtly-modest clothes could be seen, in some cases, as an offense against the Dou.

Ancient Orat also practiced a form of prima nocte. As the Shada personally owned every aspect of the kingdom, this also applied to people's bodies as well. As an assertion of this power, the Shada reserved the right to take the virginity of any young woman (or young man in some cases) who was raised in the Kreena. One dubious anecdote claims that Apef the Terrible instituted this rite by personally sleeping with every single fertile woman in the nation. While this is logistically infeasible, it is likely the rite may have started around that time. In practice, the Shada would usually defer the rite of prima nocte to high-ranking officials, allowing Kurakas to sustain their own harams.

Human sacrifice

While it is unlikely Orat had a higher suicide rate than the rest of the ancient world, there was a form of ritual suicide called kelco ("death wish"). This was believed to expedite the annihilation of the Kaba, and free them from the misery of reincarnation. This practice, however, is not mentioned in any Douist philosophic text, and is believed to be purely a folk tradition of the lower classes. Still, euthanasia was a culturally acceptable practice in Ancient Orat.

Ancient Oratians believed that weaker, less productive members of society (that is, lowest-ranked Kabas) were a detriment to the society as a whole. Konnu the Wise wrote that "the community [wawrr] is only as strong as its weakest member". Based on that belief, Ancient Orat would hold an annual festival at the beginning of spring called the "Day of Undesirables". On that day, all the physically and mentally impaired would be gathered in the city center of Dhiss, along with anyone else deemed to be the most lazy and unproductive. These people would then be publicly executed, as a kind of ritual human sacrifice. This practice did not exclude the Kuraka clans; in fact, many clans found it a matter of pride to deliver their relatives for the sacrifice, to show that they are willing to give up their lives for the good of the state. The Shada would often time the Day of Undesirables just before a major military campaign, believing that doing so will give an extra boost of power to the Social Dou.

Scholars debate how many people were killed in the Day of Undesirables, and how often it was practiced. Logistically speaking, it's unlikely to have included every single person it was qualified for, as that would be a ridiculous proportion of the nation's population. Rather, most historians believe this was instituted as a way to incentivize more productive and efficient labor from the Miqta system, and therefore only needed a sacrifice large enough to make that statement. That said, primary sources take some pride in describing the immense scale of the ritual, making such hyperboles like "the blood filled the streets as high as a horse's bridle". Ritual cannibalism was also a part of the festival, where the victims' bodies would be dismembered and filleted to be served as food for the masses. This was a kind of redemption for the sacrifice victims, showing symbolically that they can be productive in death (as a source of nourishment) which they failed to accomplish in life.