Mák’ai language: Difference between revisions

miraheze:conworlds>Javants |

No edit summary |

||

| (17 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Icons| | {{Icons|FA|PE|Paracosmic}} | ||

:''This article is part of [[Project Exodus]].'' | :''This article is part of [[Project Exodus]].'' | ||

{{Infobox language | {{Infobox language | ||

| Line 31: | Line 31: | ||

|notice = IPA | |notice = IPA | ||

}} | }} | ||

The '''Mák’ai language''', or '''Mák'ai-wa''' ([[File:Makai-wa.svg|15px]], {{Audio-IPA|Mak'aiwa.ogg|/mákʼɐ̀ɪwɐ̀/}}, literally 'people's language'), sometimes anglicised as '''Mak'ai''' or ''' | The '''Mák’ai language''', or '''Mák'ai-wa''' ([[File:Makai-wa.svg|15px]], {{Audio-IPA|Mak'aiwa.ogg|/mákʼɐ̀ɪwɐ̀/}}, literally 'people's language'), sometimes anglicised as '''Mak'ai''' or '''Maakkai''' is a [[Pan-Ejawan languages|Pan-Ejawan]] language spoken in central [[Ejawe]], predominantly on the island of [[Makaigan]]. It is the national language of [[Mák’ai]] where it is spoken by approximately TBD million people, although significant groups of Mák’ai-speakers also exist outside of Mák’ai proper. Traditionally, Mák’ai was also an important regional language as the language of the political elite in many countries under the political and/or military influence of Mák’ai, such as TBD and TBD, although gradually came to be subsumed by [[Coastal Makaigan]] as a trade language beginning around TBD. Nowadays, although not as widely spoken outside of Mák’ai as it once was, the influence of Mák’ai-wa on neighbouring languages may still be found, primarily through {{W|loan words}} and {{W|borrowings}}. | ||

Modern Mák’ai-wa is a {{W|language typology|polysynthetic}} language that implements {{W|Morphosyntactic allignment|split ergativity}} and is characterised by complex verbal morphology, the use of {{W|nominal classification|noun classifiers}}, and a relatively strict VSO sentence structure. Sentences consist at a minimum of an unconjugated lexical verb and a highly-inflected auxiliary verb, which is marked for {{W|person}}, {{W|number}}, {{W|tense}}, {{W|aspect}}, {{w|modality}}, {{w|evidentiality}}, and, to a certain extent, {{W|degree adverb|degree}}. These auxiliary verbs also exhibit {{W|incorporation (linguistics)|incorporation}}, whereby other parts of speech, typically nouns or adjectives, may be incorporated into the verb itself. Nouns in Mák’ai-wa are declined by case, of which there are six, with declension realised on obligatory but variable noun classifiers, which exhaustively divide all lexemes in Mák’ai-wa into 13 categories on the basis of function. Noun classifiers are also declined by {{W|number (linguistics)|number}}, of which there are three - {{W|singular}}, {{W|dual}}, and {{W|plural}}. Mák’ai-wa, as a Pan-Ejawan language, employs a base-12 counting system which is based on counting with the hand. | Modern Mák’ai-wa is a {{W|language typology|polysynthetic}} language that implements {{W|Morphosyntactic allignment|split ergativity}} and is characterised by complex verbal morphology, the use of {{W|nominal classification|noun classifiers}}, and a relatively strict VSO sentence structure. Sentences consist at a minimum of an unconjugated lexical verb and a highly-inflected auxiliary verb, which is marked for {{W|person}}, {{W|number}}, {{W|tense}}, {{W|aspect}}, {{w|modality}}, {{w|evidentiality}}, and, to a certain extent, {{W|degree adverb|degree}}. These auxiliary verbs also exhibit {{W|incorporation (linguistics)|incorporation}}, whereby other parts of speech, typically nouns or adjectives, may be incorporated into the verb itself. Nouns in Mák’ai-wa are declined by case, of which there are six, with declension realised on obligatory but variable noun classifiers, which exhaustively divide all lexemes in Mák’ai-wa into 13 categories on the basis of function. Noun classifiers are also declined by {{W|number (linguistics)|number}}, of which there are three - {{W|singular}}, {{W|dual}}, and {{W|plural}}. Mák’ai-wa, as a Pan-Ejawan language, employs a base-12 counting system which is based on counting with the hand. | ||

As a [[Pan-Ejawan languages|Pan-Ejawan language]], Mák’ai-wa shares a number of demonstrable geneological similarities with other [[Ejawe|Ejawan languages]], in particular the [[Raa-Makaiganic languages]] of western Ejawe. During the [[Mák’ai#Ancient Mák’ai|ancient Mák’ai]] period, Mák’ai-wa began to split off from [[Proto-Raa-Makaiganic]] in isolation on the island of [[Makaigan]], forming [[Proto-Makaiganic]]. After the settlement of the Mák’ai people near what is today [[Mkái- | As a [[Pan-Ejawan languages|Pan-Ejawan language]], Mák’ai-wa shares a number of demonstrable geneological similarities with other [[Ejawe|Ejawan languages]], in particular the [[Raa-Makaiganic languages]] of western Ejawe. During the [[Mák’ai#Ancient Mák’ai|ancient Mák’ai]] period, Mák’ai-wa began to split off from [[Proto-Raa-Makaiganic]] in isolation on the island of [[Makaigan]], forming [[Proto-Makaiganic]]. After the settlement of the Mák’ai people near what is today [[Mkái-t̗ir̗]], Mák’ai-wa came to be steadily influenced by the neighbouring [[Ktoic languages]], in particular [[Kto language|Kto]]. During this period the Mák’ai both adopted the [[Kto script|Kto writing script]] and concurrently developed [[Mák’ai logographs]], themselves derived from earlier divination practices. These two writing systems would coexist during this period until the emergence of the Mák’ai as a regional political power around TBD, at which time Mák’ai-wa developed a [[Mák’ai language#Orthography|new script]] better suited to writing the language. Earlier forms of writing, in particular Mák’ai logographs, persisted for many centuries, acting as important sources for information on the earlier stages of Mák’ai-wa. By TBD, Mák’ai-wa had become mutually unintelligible with most other varieties of [[Makaiganic languages]], and would continue to develop as the prestige language variety in Makaigan under the [[Mák’ai Empire]] in subsequent centuries. | ||

Note that throughout this article the terms 'Mák’ai language' or 'Mák’ai-wa' will be used interchangeably, as both terms are conventionally used to refer to the language. The term 'Mák’ai-wa language' is generally incorrect and will be avoided here. | Note that throughout this article the terms 'Mák’ai language' or 'Mák’ai-wa' will be used interchangeably, as both terms are conventionally used to refer to the language. The term 'Mák’ai-wa language' is generally incorrect and will be avoided here. | ||

| Line 264: | Line 264: | ||

*L | *L | ||

== | ==Writing system== | ||

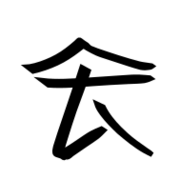

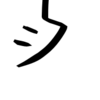

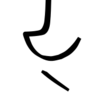

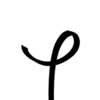

[[File:Mak'ai in Kto.svg|thumb|right|150px|The word 'Mák’ai' written in the [[Kto script]], the writing system first used to write Mák’ai-wa.]] | [[File:Mak'ai in Kto.svg|thumb|right|150px|The word 'Mák’ai' written in the [[Kto script]], the writing system first used to write Mák’ai-wa.]] | ||

Modern Mák’ai may be written using a number of different writing systems. By far the most common and standardised in the modern day is the use of [[Mák’ai script]], an {{W|alphabet|alphabetic}} writing system developed during the Middle Mák’ai-wa period. Historically, however, Mák’ai has also been written using [[Kto script]], a syllabary designed for the [[Ktoic languages]] of Eastern Makaigan that was poorly adapted to Mák’ai-wa phonology. In response to the early use of the Kto script for Mák’ai, ancient Mák’ai-wa literates developed Mák’ai logographs based on earlier divination pictograms. Mák’ai logographs were heavily used throughout the Middle Mák’ai period but had limited standardisation due to political instability and low levels of general literacy. In the 1st century [[Numur̗ian calendar|tk]], a mixed system of logographs for key words and Mák’ai script for grammatical particles was common, but was gradually replaced with the exclusive use of Mák’ai script in the modern day. Nowadays, Mák’ai logographs are commonly used as an unofficial shorthand, particularly in businesses and in personal names. | Modern Mák’ai may be written using a number of different writing systems. By far the most common and standardised in the modern day is the use of [[Mák’ai script]], an {{W|alphabet|alphabetic}} writing system developed during the Middle Mák’ai-wa period. Historically, however, Mák’ai has also been written using [[Kto script]], a syllabary designed for the [[Ktoic languages]] of Eastern Makaigan that was poorly adapted to Mák’ai-wa phonology. In response to the early use of the Kto script for Mák’ai, ancient Mák’ai-wa literates developed Mák’ai logographs based on earlier divination pictograms. Mák’ai logographs were heavily used throughout the Middle Mák’ai period but had limited standardisation due to political instability and low levels of general literacy. In the 1st century [[Numur̗ian calendar|tk]], a mixed system of logographs for key words and Mák’ai script for grammatical particles was common, but was gradually replaced with the exclusive use of Mák’ai script in the modern day. Nowadays, Mák’ai logographs are commonly used as an unofficial shorthand, particularly in businesses and in personal names. | ||

| Line 270: | Line 270: | ||

For countries which do not use the Mák’ai script, the [[Institute of Language]] in [[Mk'ái-t̗ir̗]] has developed an official romanisation using the {{W|Latin alphabet}} (see [[Mák’ai language#Phonology]] above). Alternative romanisations exist and are also given in section 5.3 below. | For countries which do not use the Mák’ai script, the [[Institute of Language]] in [[Mk'ái-t̗ir̗]] has developed an official romanisation using the {{W|Latin alphabet}} (see [[Mák’ai language#Phonology]] above). Alternative romanisations exist and are also given in section 5.3 below. | ||

===<u>1. Mák’ai script</u>=== | |||

:''Main article: [[Mák’ai script]].'' | :''Main article: [[Mák’ai script]].'' | ||

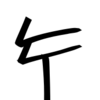

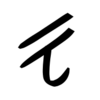

Mák’ai script is an {{W|alphabet}} consisting of 26 core segmental characters, 2 ligature (representing the high-tone diphthong ''ái'' and the syllable ''yí''), and 3 diacritics. The script is written top-down and left-to-right. Individual segments have varying forms depending on their position in a word as initial, medial, final, or in isolation. Tones are indicated through the use of separate segmental characters in the case of high-tone vowels, or through the use of diacritics in the case of low-tone vowels. These are shown below | Mák’ai script is an {{W|alphabet}} consisting of 26 core segmental characters, 2 ligature (representing the high-tone diphthong ''ái'' and the syllable ''yí''), and 3 diacritics. The script is written top-down and left-to-right. Individual segments have varying forms depending on their position in a word as initial, medial, final, or in isolation. Tones are indicated through the use of separate segmental characters in the case of high-tone vowels, or through the use of diacritics in the case of low-tone vowels. These are shown below. Mák’ai script also includes numerals corresponding to the base-12 counting system in Mák’ai-wa. These are given in the section [[Mák’ai language#4. Numbers]] below. | ||

{| class="wikitable" | {| class="wikitable" | ||

| Line 350: | Line 350: | ||

| [[File:Ng - medial.svg|100px]] | | [[File:Ng - medial.svg|100px]] | ||

| [[File:Ng - final.svg|100px]] | | [[File:Ng - final.svg|100px]] | ||

| | |||

| | | | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 455: | Line 456: | ||

| [[File:M - initial.svg|100px]] | | [[File:M - initial.svg|100px]] | ||

| [[File:M - medial.svg|100px]] | | [[File:M - medial.svg|100px]] | ||

| [[File:m - | | [[File:m - final.svg|100px]] | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| Line 462: | Line 463: | ||

| tj | | tj | ||

| t͡ʃ | | t͡ʃ | ||

| [[File:Tj - initial.svg|100px]] | |||

| [[File:Tj - medial.svg|100px]] | |||

| [[File:Tj - final.svg|100px]] | |||

| | |||

| | |||

|- | |- | ||

| ''já'' | | ''já'' | ||

| j | | j | ||

| d͡ʒ | | d͡ʒ | ||

| [[File:J - initial.svg|100px]] | |||

| [[File:J - medial.svg|100px]] | |||

| [[File:J - final.svg|100px]] | |||

| | |||

| | |||

|- | |- | ||

| ''r̗á'' | | ''r̗á'' | ||

| r̗ | | r̗ | ||

| r | | r | ||

| [[File:Rh - initial.svg|100px]] | |||

| [[File:Rh - medial.svg|100px]] | |||

| [[File:Rh - final.svg|100px]] | |||

| | |||

| | |||

|- | |- | ||

| ''ar'' | | ''ar'' | ||

| r | | r | ||

| ɹ̠ | | ɹ̠ | ||

| [[File:R - initial.svg|100px]] | |||

| [[File:R - medial.svg|100px]] | |||

| [[File:R - final.svg|100px]] | |||

| | |||

| | |||

|- | |- | ||

| ''wá'' | | ''wá'' | ||

| w | | w | ||

| w | | w | ||

| [[File:W - initial.svg|100px]] | |||

| [[File:W - medial.svg|100px]] | |||

| [[File:W - final.svg|100px]] | |||

| | |||

| | |||

|- | |- | ||

| ''l̗á'' | | ''l̗á'' | ||

| l̗ | | l̗ | ||

| l̪ | | l̪ | ||

| [[File:L - initial.svg|100px]] | |||

| [[File:L - medial.svg|100px]] | |||

| [[File:L - final.svg|100px]] | |||

| | |||

| | |||

|- | |- | ||

| ''lá'' | | ''lá'' | ||

| l | | l | ||

| l̠ | | l̠ | ||

| [[File:L (real) - initial.svg|100px]] | |||

| [[File:L (real) - medial.svg|100px]] | |||

| [[File:L (real) - final.svg|100px]] | |||

| | |||

| | |||

|- | |- | ||

! colspan="8"| Ligatures: | ! colspan="8"| Ligatures: | ||

| Line 503: | Line 539: | ||

| [[File:yi - initial.svg|100px]] | | [[File:yi - initial.svg|100px]] | ||

| [[File:yi - medial.svg|100px]] | | [[File:yi - medial.svg|100px]] | ||

| [[File:yi - | | [[File:yi - final.svg|100px]] | ||

| | | | ||

| Used instead of duplicating the segment for y/í. | | Used instead of duplicating the segment for y/í. | ||

| Line 528: | Line 564: | ||

|- | |- | ||

! colspan="8"| Punctuation: | ! colspan="8"| Punctuation: | ||

|- | |||

| ''áwuk tak'' | |||

| - | |||

| n/a | |||

| colspan="4"| [[File:Aawuk tak.svg|100px]] | |||

| Used to link noun classifiers to their head nouns. Converts final segment of preceding noun to a medial form with an extended tail that links to the classifier. | |||

|- | |||

| ''n̗ajún̗'' | |||

| . | |||

| n/a | |||

| colspan="4"| [[File:Nhajuunh.svg|100px]] | |||

| Equivalent to a full stop in English. Not connected to main word. | |||

|- | |||

| ''taktak'' | |||

| , | |||

| n/a | |||

| colspan="4"| [[File:Taktak.svg|100px]] | |||

| Used as a comma in lists. Not connect to main word. | |||

|} | |} | ||

===<u>2. Mák’ai logographs</u>=== | |||

:''Main article: [[Mák’ai logographs]].'' | |||

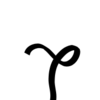

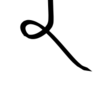

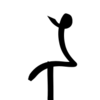

Mák’ai logographs were historically used as the primary means of writing Mák’ai-wa, and in most cases texts from earlier stages of Mák’ai-wa are written exclusively using logographs. Following the development and official adoption of the Mák’ai alphabet four centuries ago, however, the use of Mák’ai logographs in everyday contexts has gradually decreased. Of the some 40,000 documented Mák’ai logographs that exist in the historical record, less than 1,000 are in common usage today. A much higher number of logographs are maintained in personal names, in particular last names, of which there are relatively few in modern [[Mák’ai]]. Logographs are otherwise commonly used in shorthand or in signs, such as the character TBD, which is usually used to indicate a grocery store or supermarket. School children in Mák’ai are taught the most common characters in school, but are typically not taught enough to be able to exclusively write using logographs. A few common logographs are given below (hover to see the translation): | |||

====<u> | <gallery mode="packed-hover"> | ||

See.svg|''palí'', 'to see', 'sight' | |||

Shop logograph.svg|''wulung'', 'shop' | |||

Makai-wa.svg|''Mák’ai-wa'', 'Mák’ai language'. | |||

House logograph.svg|''ḿt̗a'', 'house', 'home' | |||

Maarduk.svg|''[[Gender and sexuality in Mák’ai#Márduk|márduk]]'' | |||

</gallery> | |||

===<u>3. Alternative romanisations</u>=== | |||

Mák’ai-wa also has a number of alternative romanisations. The most common of these is given below, and is predominantly used in cases where it is difficult to type diacritics: | Mák’ai-wa also has a number of alternative romanisations. The most common of these is given below, and is predominantly used in cases where it is difficult to type diacritics: | ||

*Tones may be written as double letters - 'á' as '''aa''', 'í' as '''ii''', and 'ú' as '''uu'''. | *Tones may be written as double letters - 'á' as '''aa''', 'í' as '''ii''', and 'ú' as '''uu'''. | ||

| Line 1,615: | Line 1,679: | ||

===<u>3. Adjectives and adverbs</u>=== | ===<u>3. Adjectives and adverbs</u>=== | ||

{{Mak'ai word of the day}} | |||

====<u>3.1 Adjectives</u>==== | ====<u>3.1 Adjectives</u>==== | ||

Adjectives, adverbs, and other modifiers in Mák’ai are relatively simple. Modifiers of nouns occur after the head and are introduced by the particle ''d̗a'' or ''nga''. ''d̗a'' is used for {{W|alienable possession}} - that is, where the attribute given to the noun is something which can be lost; while ''nga'' is used for {{W|inalienable possession}} - that is, where the attribute given to the noun is something which cannot be lost. Note that this is used seperately to the {{W|genitive case}}, which is used where one noun possesses another. Furthermore, adjectives are not modified in any way to agree with the noun, as syntax always indicates which noun the adjectives are modifying. Examples of these are as follows: | Adjectives, adverbs, and other modifiers in Mák’ai are relatively simple. Modifiers of nouns occur after the head and are introduced by the particle ''d̗a'' or ''nga''. ''d̗a'' is used for {{W|alienable possession}} - that is, where the attribute given to the noun is something which can be lost; while ''nga'' is used for {{W|inalienable possession}} - that is, where the attribute given to the noun is something which cannot be lost. Note that this is used seperately to the {{W|genitive case}}, which is used where one noun possesses another. Furthermore, adjectives are not modified in any way to agree with the noun, as syntax always indicates which noun the adjectives are modifying. Examples of these are as follows: | ||

| Line 1,867: | Line 1,932: | ||

====<u>4.2 Ordinals and other number derivations</u>==== | ====<u>4.2 Ordinals and other number derivations</u>==== | ||

Ordinals in Mák’ai are formed by adding the particle ''kí'' before the number. For example, 'first' is ''kí yúgí'', 'second' is ''kí yúbá'', 'tenth' is ''kí mángí'', etc. Fractions are formed using genitive nominal classifiers in combination with an ordinal, as in ''kí yúgí t̗abá-ngur'', 'one fifth', or literally, 'first of five'. Note that the generic classifier ''nga'' is always used for fractional numbers. | Ordinals in Mák’ai are formed by adding the particle ''kí'' before the number. For example, 'first' is ''kí yúgí'', 'second' is ''kí yúbá'', 'tenth' is ''kí mángí'', etc. Fractions are formed using genitive nominal classifiers in combination with an ordinal, as in ''kí yúgí t̗abá-ngur'', 'one fifth', or literally, 'first of five'. Note that the generic classifier ''nga'' is always used for fractional numbers. | ||

====<u>4.3 Writing numerals and ordinals</u>==== | |||

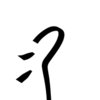

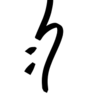

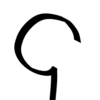

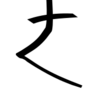

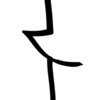

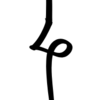

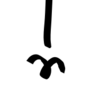

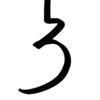

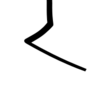

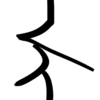

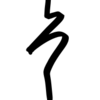

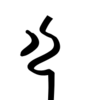

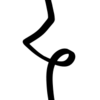

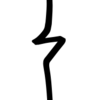

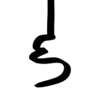

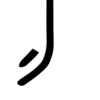

Mák’ai uses [[Mák’ai script#Numerals|Mák’ai numerals]] for numbers and ordinals in writing. Numerals are written using a {{W|place-value system}} in which there is a basic character for each of the 12 basic numerals. Moving from right to left, each number represents one place value. The corresponding word for that place value (ie, ''du'' or ''payu'') is therefore not written, but pronounced when the number is read aloud. For example, 472 in Mák’ai is ''t̗agí payu t̗agí du yúju'', which would be written as 4-4-3, or [[File:tagi.svg|15px]][[File:tagi.svg|15px]][[File:yuju.svg|15px]] (note however that numbers are normally written top-down, as is the rest of Mák’ai script). | |||

The basic forms of these 12 numerals are as follows. They are derived from pictographs of the hand, based on the traditional counting method of the Mák’ai people illustrated in the video above. | |||

{| class="wikitable" | |||

|+ Cardinal numbers in Mák’ai | |||

|- | |||

! Character | |||

! Number | |||

! Mák’ai | |||

|- | |||

| [[File:Yugi.svg|100px]] | |||

| 1 | |||

| ''yúgí'' | |||

|- | |||

| [[File:Yuba.svg|100px]] | |||

| 2 | |||

| ''yúbá'' | |||

|- | |||

| [[File:Yuju.svg|100px]] | |||

| 3 | |||

| ''yúju'' | |||

|- | |||

| [[File:Tagi.svg|100px]] | |||

| 4 | |||

| ''t̗agí'' | |||

|- | |||

| [[File:Taba.svg|100px]] | |||

| 5 | |||

| ''t̗abá'' | |||

|- | |||

| [[File:Taju.svg|100px]] | |||

| 6 | |||

| ''t̗aju'' | |||

|- | |||

| [[File:Wugi.svg|100px]] | |||

| 7 | |||

| ''wugí'' | |||

|- | |||

| [[File:Wuba.svg|100px]] | |||

| 8 | |||

| ''wubá'' | |||

|- | |||

| [[File:Wuju.svg|100px]] | |||

| 9 | |||

| ''wuju'' | |||

|- | |||

| [[File:Mangi.svg|100px]] | |||

| 10 | |||

| ''mángí'' | |||

|- | |||

| [[File:Manba.svg|100px]] | |||

| 11 | |||

| ''mánbá'' | |||

|- | |||

| [[File:Manju Mak'ai.svg|100px]] | |||

| 12 | |||

| ''mánju'' | |||

|} | |||

===<u>5. Syntax</u>=== | ===<u>5. Syntax</u>=== | ||

{{Mak'ai language}} | |||

Mák’ai-wa syntax is relatively free on the basis of information flow. Unmarked sentence structure is {{W|Syntax|VSO}}, consisting of an obligatory auxiliary verb inflected for person, number, and agreement, followed by an uninflected lexical verb, the subject nominal phrase, the object nominal phrase, and any additional oblique phrases. | Mák’ai-wa syntax is relatively free on the basis of information flow. Unmarked sentence structure is {{W|Syntax|VSO}}, consisting of an obligatory auxiliary verb inflected for person, number, and agreement, followed by an uninflected lexical verb, the subject nominal phrase, the object nominal phrase, and any additional oblique phrases. | ||

Latest revision as of 23:46, 17 November 2024

- This article is part of Project Exodus.

| Mák’ai language | |

|---|---|

|

Mák’ai-wa | |

Above: Mák’ai-wa written in traditional Mák’ai logographs. Below: Mák’ai-wa written in Mák’ai script calligraphy. | |

| Region | Central Ejawe, Makaigan |

| Ethnicity | Mák’ai |

|

Pan-Ejawan

| |

Early forms | |

| Mák’ai script (officially), Mák’ai logographs (often), Kto script (historically). | |

| Makaiganic Sign Language | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | Mák’ai |

| Regulated by | Institute of Language, Mk'ái-t̗ir̗ |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 |

mk |

| ISO 639-2 |

mkw |

| ISO 639-3 |

mkw |

The Mák’ai language, or Mák'ai-wa (![]() ,

, ![]() [[:Media:Mak'aiwa.ogg|/mákʼɐ̀ɪwɐ̀/]] (help·info), literally 'people's language'), sometimes anglicised as Mak'ai or Maakkai is a Pan-Ejawan language spoken in central Ejawe, predominantly on the island of Makaigan. It is the national language of Mák’ai where it is spoken by approximately TBD million people, although significant groups of Mák’ai-speakers also exist outside of Mák’ai proper. Traditionally, Mák’ai was also an important regional language as the language of the political elite in many countries under the political and/or military influence of Mák’ai, such as TBD and TBD, although gradually came to be subsumed by Coastal Makaigan as a trade language beginning around TBD. Nowadays, although not as widely spoken outside of Mák’ai as it once was, the influence of Mák’ai-wa on neighbouring languages may still be found, primarily through loan words and borrowings.

[[:Media:Mak'aiwa.ogg|/mákʼɐ̀ɪwɐ̀/]] (help·info), literally 'people's language'), sometimes anglicised as Mak'ai or Maakkai is a Pan-Ejawan language spoken in central Ejawe, predominantly on the island of Makaigan. It is the national language of Mák’ai where it is spoken by approximately TBD million people, although significant groups of Mák’ai-speakers also exist outside of Mák’ai proper. Traditionally, Mák’ai was also an important regional language as the language of the political elite in many countries under the political and/or military influence of Mák’ai, such as TBD and TBD, although gradually came to be subsumed by Coastal Makaigan as a trade language beginning around TBD. Nowadays, although not as widely spoken outside of Mák’ai as it once was, the influence of Mák’ai-wa on neighbouring languages may still be found, primarily through loan words and borrowings.

Modern Mák’ai-wa is a polysynthetic language that implements split ergativity and is characterised by complex verbal morphology, the use of noun classifiers, and a relatively strict VSO sentence structure. Sentences consist at a minimum of an unconjugated lexical verb and a highly-inflected auxiliary verb, which is marked for person, number, tense, aspect, modality, evidentiality, and, to a certain extent, degree. These auxiliary verbs also exhibit incorporation, whereby other parts of speech, typically nouns or adjectives, may be incorporated into the verb itself. Nouns in Mák’ai-wa are declined by case, of which there are six, with declension realised on obligatory but variable noun classifiers, which exhaustively divide all lexemes in Mák’ai-wa into 13 categories on the basis of function. Noun classifiers are also declined by number, of which there are three - singular, dual, and plural. Mák’ai-wa, as a Pan-Ejawan language, employs a base-12 counting system which is based on counting with the hand.

As a Pan-Ejawan language, Mák’ai-wa shares a number of demonstrable geneological similarities with other Ejawan languages, in particular the Raa-Makaiganic languages of western Ejawe. During the ancient Mák’ai period, Mák’ai-wa began to split off from Proto-Raa-Makaiganic in isolation on the island of Makaigan, forming Proto-Makaiganic. After the settlement of the Mák’ai people near what is today Mkái-t̗ir̗, Mák’ai-wa came to be steadily influenced by the neighbouring Ktoic languages, in particular Kto. During this period the Mák’ai both adopted the Kto writing script and concurrently developed Mák’ai logographs, themselves derived from earlier divination practices. These two writing systems would coexist during this period until the emergence of the Mák’ai as a regional political power around TBD, at which time Mák’ai-wa developed a new script better suited to writing the language. Earlier forms of writing, in particular Mák’ai logographs, persisted for many centuries, acting as important sources for information on the earlier stages of Mák’ai-wa. By TBD, Mák’ai-wa had become mutually unintelligible with most other varieties of Makaiganic languages, and would continue to develop as the prestige language variety in Makaigan under the Mák’ai Empire in subsequent centuries.

Note that throughout this article the terms 'Mák’ai language' or 'Mák’ai-wa' will be used interchangeably, as both terms are conventionally used to refer to the language. The term 'Mák’ai-wa language' is generally incorrect and will be avoided here.

History

1. Old Mák’ai-wa

- Main article: Old Mák’ai-wa.

Modern evidence suggests that Mák’ai-wa first began to deviate from Proto-Makaiganic, itself a subbranch of the Raa-Makaiganic languages, around TBD. At this stage, the Makaiganic languages formed part of a broader dialect continuum running north-south in Makaigan. As a result, Mák’ai-wa distinguished itself from the northern Makaiganic languages of Northern Tjuwa and T'umak at a much earlier stage than it did from the southern languages of Wák'ai and Ngumaya-wa, maintaining a relatively high level of mutual intelligibility well into the TBD century. It was around TBD, after Mák’ai's initial deviation from northern and central Makaiganic languages, that Mák’ai-wa began to be written down. As a result of extensive trade and contact with the much more advanced Kto people of eastern Makaigan, Mák’ai-wa came to be written using Kto script. The earliest documentation of the Old Mák’ai-wa language from this period come from Ktoic documents describing the language of the Mák’ai, with whom they traded. Later, literacy would increase among the Mák’ai themselves, as they began using a modified version of the Kto script for early poetry and trade documents.

Concurrently to the adoption of Kto script, traditional Mák’ai-wa shamans also developed Mák’ai logographs as a form of early divination. Gradually, the use of Kto script came to be at least partially supplanted by these Mák’ai logographs, largely as a result of the unsuitability of the Kto script to convey phonological differences in Mák’ai-wa. By the TBD century, almost all Mák’ai-wa texts were written exclusively using logographs. The logographic systems used through Mák’ai were, however, disunified, and uses of characters varied significantly across Mák’ai territory. This problem was exacerbated by political disunity during this period, which prevented the creation of a single, codified logographic system.

Old Mák’ai-wa was itself substantially different from modern Mák’ai-wa in terms of its grammar and vocabulary. Mák’ai-wa has remained relatively phonologically stable since its evolution from Proto-Makaiganic but has undergone significant grammatical changes. Most dramatic of these is the significant reduction in grammatical complexity for verbal paradigms. Notably, verbs in Old Mák’ai-wa were additionally conjugated for politeness, with a four-tiered system of deference. Additionally, there were multiple auxiliary verbs which could be used which had their own semantic meanings depending on the type of action occurring. An example of this is given below, with the same sentence in Old Mák’ai-wa and Modern Mák’ai-wa for comparison:

Old Mák’ai-wa: T̗ák’ísnuduwkh'a'nkhámut̗ kh'ung ayír'thá butuk nawwat̗á-k’ís-nu-duw-kh'a'l-khámut̗

DIST-2.SG.NOM-DU.MASC-3.SG.INANIM.ACC-move.using.hands.PST-DEF

kh'ung

throw

ayír'thá

stick

butuk

red

nawwa

NC:tool.SG.INST

'You two Ngárduk, whom I highly respect, threw the red stick.'

Modern Mák’ai-wa: Nngaírul k'ung átá-na káiyanngaí-ru-l

2.DU.NOM.MASC-3.SG.ACC.INANIM.PROX-PST

k'ung

throw

átá-na

stick-NC:tool.SG.INST

káiya

red

'You two Ngárduk threw the red stick.'

Note the high level of grammaticalization that has occurred in the Modern Mák’ai-wa auxiliary - the original semantic distinctions based on movement type have disappeared, and productive agglutinating processes for pronoun formation have since become more obscure. Note that the degree of similarity between older and modern pronominal forms in Mák’ai-wa varies considerably. For example, the dual '-nu' suffix is absent in the Modern Mák’ai-wa second person dual, but present in the third person dual form kúngnu. Besides these differences in pronominal forms, there is also no grammatical means of encoding the politeness information present in the Old Mák’ai-wa example. Syntactic change is also evident in the broader clause - in Old Mák’ai-wa, noun classifiers existed as postpositions appended at the end of the entire phrase, rather than as nominal affixes, as is the case in Modern Mák’ai-wa.

2. Middle Mák’ai-wa

- Main article: Middle Mák’ai-wa.

By the Middle Mák’ai-wa period, beginning around TBD, the state of Mák’ai itself had centralised to the point that efforts towards language unification became viable. Under TBD, a new Mák’ai script was developed to replace the disjointed logographic system. An alphabetical system based off the Kto script, which was still in limited use for documenting Mák’ai-wa itself, was created. For subsequent centuries, the new Mák’ai script came to be used almost exclusively in court, with the supplementary use of particular common logographs. This blended orthographic system was common until well into the modern era, when the Mák’ai state officially decreed Mák’ai script as the sole means of writing Mák’ai-wa in the Literacy Act of TBD.

During this period, Mák’ai as a political entity came to be increasingly influential. As a result of political expansion and increased contact with neighbouring languages, Mák’ai-wa changed both in terms of its grammar and its lexicon. Numerous new loan words were adopted for foreign concepts, particularly from the eastern Kto people and the people of Nungái-la. In particular, as a result of the increased number of foreign-language learners of Mák’ai-wa who had been brought into the Mák’ai state, Mák’ai-wa's grammar began to simplify. Many of the most complex aspects of Old Mák’ai-wa grammar, such as the formality distinctions and differences in auxiliary verbs, ceased to be productive. This process of grammatical simplification was long and uneven over the course of the Middle Mák’ai-wa period, but eventuated in a grammatical system much more similar to what is found in Mák’ai-wa today.

An example of a sentence in Middle Mák’ai-wa is given below:

Middle Mák’ai-wa: Nngaínuruwal k'ung áytá káiya nawnngaí-nu-ruw-al

2.NOM.MASC-DU-3.SG.ACC.INANIM.PROX-PST

k'ung

throw

áytá

stick

káiya

red

naw

NC:tool.SG.INST

'You two Ngárduk threw the red stick.'

Note the relative simplification of the verbal morphology when compared to the Old Mák’ai-wa example above, as well as the adoption of the foreign loan word káiya from Ktai. It is also important to note that Mák’ai-wa syntax was in a considerable state of flux during this Middle Mák’ai-wa period, most notably in that nominal classifiers were transitioning from phrasal clitics to nominal suffixes. This is seen in the mutual attestation of the sentence given above as well as the alternative form nngaínuruwal k'ung áytá-naw káiya, dated to TBD and TBD respectively. The Middle Mák’ai-wa period can hence be seen as a period of grammatical flux between the more complex grammatical structures of Old Mák’ai-wa and the grammar of Modern Mák’ai-wa found today.

3. Modern Mák’ai-wa

Mák’ai-wa came to resemble what is now considered its modern form beginning around TBD, when a series of legal reforms under TBD resulted in the establishment of the centralised Institute for Language in Mk'ái-t̗ir̗. This was coupled with the production of the first Mák’ai-wa dictionary in TBD and saw a period of rapid linguistic codification and standardisation of rules of spelling and grammar. While Mák’ai-wa grammar has unavoidably continued to change in subsequent centuries, speakers of Mák’ai-wa usually have very little difficulty understanding Mák’ai-wa texts from the Modern period as a result of this standardisation, with the exception of changes in lexical meaning.

This period also saw the rise of many of Mák’ai's greatest literary figures who helped establish Modern Mák’ai-wa as an important cultural language. Figures such as Káiya Lak, Girá Nggút̗ir̗, and Makawu R̗ú are well known authors who helped establish the Modern Mák’ai-wa language.

Distribution

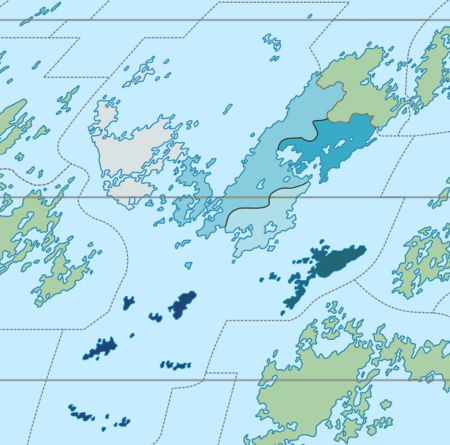

|

Countries with a significant portion of Mák’ai-wa speakers in diaspora, or where Mák’ai-wa has had historic importance (Nga, the Ktoic Confederacy, and Kstania)

| |

As of TBD, there are approximately TBD million speakers of Mák’ai-wa globally. In the modern world, Mák’ai-wa is only an official language in one state - Mák’ai - which is also the state in which the majority of its speakers are found. Historically, however, Mák’ai-wa was spoken to a much higher extent outside of Mák’ai proper as a result of the expansion of the Mák’ai Empire in TBD. As a result, minority groups of Mák’ai speakers are now found in many of the places where Mák’ai-wa was formerly spoken to a much larger extent, including western Ejawe, primarily Mtasai, and in some parts of Nga. The largest groups of Mák’ai speakers outside of Mák’ai proper are found in Mtasai and Imai, although Mák’ai-wa is not recognised as an official language in either state.

As a result of the regional importance of Mák’ai in Ejawe, however, Mák'ai-wa has a growing number of second language learners in addition to its communities in diaspora. The largest countries in which Mák’ai-wa is taught as a second language are its closest neighbours of Mtasai, Imai, and Nga, themselves unsurprisingly the countries with the highest populations of Mák’ai-wa speakers outside of Mák’ai. Outside of Ejawe proper, many university-level Mák’ai-wa programs exist, most notably in the countries of TBD and TBD. The relatively limited use of Mák’ai-wa within Ejawe has meant, however, that foreign language programs are usually limited to specialised areas of study abroad. As a result, Mák’ai-wa is rarely taught below a university level in countries outside of Ejawe.

Classification

Mák’ai is a Pan-Ejawan language belonging to the Makaiganic subgroup of the Raa-Makaiganic subfamily. As a Pan-Ejawan language, Mák’ai exhibits characteristics common to most other languages in Ejawe, including noun classifiers, VSO sentence structure, and the use of an undeclined lexical verb in combination with a morphologically complex auxiliary verb. Mák’ai, along with the other Raa-Makaiganic languages, split off from Proto-Pan-Ejawan with the isolation of the western Ejawan people on Makaigan around TBD. As continued migration westward led to the isolation of the Makaigan Ejawans from the Raa-Mtasaic peoples of Mtasai and Raa, Proto-Makaigan began to separate itself from other Ejawan languages, losing many of the phonological features of its related languages and developing simple tone systems. Mák’ai-wa would later diverge from other languages on the Makaiganic dialect continuum around TBD. Its most closely related living languages today are the minority languages of Ánagai and Lárk'ai-wa, as well as the endangered languages of Wák'ai and Ngumaya-wa, all of which are southern and central Makaiganic languages. Mák’ai is also closely related to the derived language of Coastal Makaigan - a form of trade creole derived primarily from Mák’ai-wa, Nga, and Kto during the TBD century as a common trading language around the Ejawan Sea and Sea of Nga.

Mák’ai-wa was subject to a number of significant phonological shifts in its early stages, which further served to differentiate it and the other Makaiganic languages from other Pan-Ejawan languages. Most notable of these changes was the near complete loss of fricative sounds, which are maintained in all other subfamilies of Pan-Ejawan to a greater or lesser extent. This decrease in consonantal breadth is hypothesized to be part of the cause for the laminal-apical consonant distinction that emerged in Makaiganic languages to a greater extent than other Pan-Ejawan languages, although a scientific consensus is yet to be reached to confirm that this was the case.

Mák’ai-wa vocabulary is considerably different from other western Raa-Makaiganic languages as a result of the influence of the neighbouring Ktoic languages, in particular Kto, which was instrumental in influencing earlier stages of Mák’ai as a prestige language variety on Makaigan. Around 15% of modern Mák’ai's vocabulary originates from Kto, a much higher proportion than any other Raa-Makaiganic language. As a result, Mák’ai is not mutually intelligible with any other language in Ejawe with the possible exception of the endangered Wák'ai language, itself having also been subjected to the influence of Ktoic languages to a similar extent. Furthermore, dialects of Mák’ai-wa spoken in areas near Ktoic languages, in particular in the east of modern-day Mák’ai, exhibit higher degrees of Ktoic influence on their vocabulary than Standard Mák’ai, with a large degree of language mixture having historically occurred in this region.

Phonology

- Main article: Mák’ai-wa phonology.

1. Consonants

The Mák’ai language has a consonant inventory consisting of five places and six manners of articulation, along with a lateral/central distinction for approximants. Mák’ai-wa employs both pulmonic and non-pulmonic ejective consonants. Modal voice is its only form of phonation, although creaky voice may sometimes occur allophonically in low tones (see section on tone below). Oral stops and ejectives come in contrasting aspirated/unaspirated pairs, with aspirated stops having an average voice onset lag of approximately 150 milliseconds and unaspirated stops an average lag of approximately 15 milliseconds. True voicing is only contrastive for nasals, which come in voiced/devoiced pairs. These contrasts are summarised in the table below. Note that the orthographic representation of each phoneme is given in angled brackets before the corrosponding IPA symbol.

| Bilabial | Lamino-dental | Apico-postalveolar | Palatal | Velar | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ejective plosive | ⟨t̗'⟩ t̪ʼ | ⟨t'⟩ t̠ʼ | ⟨k'⟩ kʼ | |||

| Pulmonic plosive | Aspirated | ⟨p⟩ pʰ | ⟨t̗⟩ t̪ʰ | ⟨t⟩ t̠ʰ | ⟨k⟩ kʰ | |

| Unaspirated | ⟨b⟩ p | ⟨d̗⟩ t̪ | ⟨d⟩ t̠ | ⟨g⟩ k | ||

| Affricate | Aspirated | ⟨tj⟩ t̠͡ʃ̠ʰ | ||||

| Unaspirated | ⟨j⟩ t̠͡ʃ̠ | |||||

| Nasal | ⟨m⟩ m | ⟨n̗⟩ n̪ | ⟨n⟩ n̠ | ⟨ng⟩ ŋ | ||

| Trill | ⟨r̗⟩ r̪ ~ r * | |||||

| Approximant | ⟨w⟩ <w> | ⟨r⟩ ɹ̠ | ⟨y⟩ j | ⟨w⟩ <w> | ||

| Lateral approximant | ⟨l̗⟩ l̪ | ⟨l⟩ l̠ | ||||

2. Vowels

Mák’ai-wa has a very simple three vowel system, consisting of three monophthongs and one diphthong. The lack of significant distinction within the vowel space means that there are great deals of allophonic variation in the production of vowels in Mák’ai-wa, some of which is unpredictable. The vowel system of Mák’ai-wa may be illustrated as follows:

| Front | Back | |

|---|---|---|

| Close | ⟨i⟩ i~ɪ | ⟨u⟩ u~ʊ |

| Open | ⟨a⟩ a~ɐ~ə | |

| Diphthong | ⟨ai⟩ aɪ~ɐɪ~əɪ | |

There has been some historical debate over the status of the phonemic status of the diphthong /aɪ/ above, with some theorists arguing that it is better analysed as a series of two vowels. Modern analysts tend to note two distinct phonotactic patterns in Mák’ai-wa which have different realisations resulting in this possible interpretation. Firstly, /aɪ/ can occur as a single phonemic diphthong with one tonal segmental over the entire vowel, as in a word like áigu 'warm', or /aɪ/ can occur as a sequence of two syllables, hence rendering it more accurately /a.ɪ/. In this latter case, high tone on one but not the other segment may lead to a rising or falling contour tone, as in ngaí (a pronoun).

3. Tones

Mák’ai-wa is a register tone language with two tone levels - high, marked orthographically by an acute accent, and low, which remains unmarked in its orthography. Tonemes occur on both vowels and sonorants. There is a marginal third, central tone, which appears only in reduced syllables in particular phonemic environments. Contour tones also occur in some words, but usually occur only as a result of morphological or historical processes. Examples of the tones of Mák’ai-wa are as follows:

| Tone type | Mák’ai-wa | IPA | Audio | Translation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High | nk'á | [ǹ̠kʼá] | 'god, deity' | |

| Low | nk'a | [ǹ̠kʼà] | 'bird' | |

| Reduced/Central | nk'a w k'á | [ǹ̠kʼà w̄ k'á] | 'bird and horse' | |

| Rising | nka-á | [ǹ̠kʼǎ] | 'the Bird-God (accusative)' | |

| Falling | nká-a | [ǹ̠kʼâ] | 'God' |

4. Phonotactics

Syllables in Mák’ai-wa are relatively simple. All consonants consist of a nucleus which may either be a vowel, liquid, or nasal. Syllables may have a single consonant onset and/or coda, with only non-bilabial aspirated plosives or nasals or rhotics being possible coda consonants. Syllables where the nucleus is a nasal or liquid consonant cannot have an additional onset or coda syllable. Furthermore, diphthongs typically do not take codas. As such, the following syllable structures in Mák’ai-wa are as followsː

- (C)V(C)

- N

- L

Writing system

Modern Mák’ai may be written using a number of different writing systems. By far the most common and standardised in the modern day is the use of Mák’ai script, an alphabetic writing system developed during the Middle Mák’ai-wa period. Historically, however, Mák’ai has also been written using Kto script, a syllabary designed for the Ktoic languages of Eastern Makaigan that was poorly adapted to Mák’ai-wa phonology. In response to the early use of the Kto script for Mák’ai, ancient Mák’ai-wa literates developed Mák’ai logographs based on earlier divination pictograms. Mák’ai logographs were heavily used throughout the Middle Mák’ai period but had limited standardisation due to political instability and low levels of general literacy. In the 1st century tk, a mixed system of logographs for key words and Mák’ai script for grammatical particles was common, but was gradually replaced with the exclusive use of Mák’ai script in the modern day. Nowadays, Mák’ai logographs are commonly used as an unofficial shorthand, particularly in businesses and in personal names.

For countries which do not use the Mák’ai script, the Institute of Language in Mk'ái-t̗ir̗ has developed an official romanisation using the Latin alphabet (see Mák’ai language#Phonology above). Alternative romanisations exist and are also given in section 5.3 below.

1. Mák’ai script

- Main article: Mák’ai script.

Mák’ai script is an alphabet consisting of 26 core segmental characters, 2 ligature (representing the high-tone diphthong ái and the syllable yí), and 3 diacritics. The script is written top-down and left-to-right. Individual segments have varying forms depending on their position in a word as initial, medial, final, or in isolation. Tones are indicated through the use of separate segmental characters in the case of high-tone vowels, or through the use of diacritics in the case of low-tone vowels. These are shown below. Mák’ai script also includes numerals corresponding to the base-12 counting system in Mák’ai-wa. These are given in the section Mák’ai language#4. Numbers below.

| Name | Romanisation | IPA equivalent | Forms | Notes | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial | Medial | Final | Isolated | ||||

| Segments: | |||||||

| ai tak | ai | àɪ |

|

|

|

Exclusively low-tone, see ligature below for high-tone variant. | |

| á r̗í | á | á |

|

|

|

Medial form may optionally be connected to subsequent segment, but is traditionally separate. | |

| í r̗í | í/y | ɪ́, j |

|

|

|

See ligatures below for yí, which would otherwise result in this segment duplicated. | |

| ú r̗í | ú | ʊ́ |

|

|

|

||

| n̗á | n̗ | n̪ |

|

|

|

||

| an | n | n̠ |

|

|

|

||

| ang | ng | ŋ |

|

|

|

||

| t̗'á | t̗' | t̪ʼ |

|

|

|

||

| t̗á | t̗ | t̪ |

|

|

|

||

| d̗á | d̗ | d̪ |

|

|

|

||

| t'á | t' | t̠' |

|

|

|

||

| tá | t | t̠ |

|

|

|

||

| dá | d | d̠ |

|

|

|

||

| k'á | k' | k' |

|

|

|

||

| ká | k | k |

|

|

|

||

| gá | g | g |

|

|

|

||

| pá | p | p |

|

|

|

||

| bá | b | b |

|

|

|

||

| am | m | m |

|

|

|

||

| tjá | tj | t͡ʃ |

|

|

|

||

| já | j | d͡ʒ |

|

|

|

||

| r̗á | r̗ | r |

|

|

|

||

| ar | r | ɹ̠ |

|

|

|

||

| wá | w | w |

|

|

|

||

| l̗á | l̗ | l̪ |

|

|

|

||

| lá | l | l̠ |

|

|

|

||

| Ligatures: | |||||||

| ái r̗í | ái | áɪ |

|

|

|

Used exclusively for high tone. Individual segment used for low tone. | |

| yí | yí | jɪ́ |

|

|

|

Used instead of duplicating the segment for y/í. | |

| Low-tone vowel diacritics: | |||||||

| a tak | a | à |

|

Placed to the right of the main segment to form a syllable. Typically placed in the bottom right, unless main segment has a right-facing descender (ie, k), in which case placed in the top right. | |||

| i tak | i | ɪ̀ |

|

Placed to the centre left of the main segment to form a syllable. May be placed to the right instead if the main segment is left heavy (ie, m). | |||

| u tak | u | ù |

|

Placed to the centre right of the main segment. | |||

| Punctuation: | |||||||

| áwuk tak | - | n/a |

|

Used to link noun classifiers to their head nouns. Converts final segment of preceding noun to a medial form with an extended tail that links to the classifier. | |||

| n̗ajún̗ | . | n/a |

|

Equivalent to a full stop in English. Not connected to main word. | |||

| taktak | , | n/a |

|

Used as a comma in lists. Not connect to main word. | |||

2. Mák’ai logographs

- Main article: Mák’ai logographs.

Mák’ai logographs were historically used as the primary means of writing Mák’ai-wa, and in most cases texts from earlier stages of Mák’ai-wa are written exclusively using logographs. Following the development and official adoption of the Mák’ai alphabet four centuries ago, however, the use of Mák’ai logographs in everyday contexts has gradually decreased. Of the some 40,000 documented Mák’ai logographs that exist in the historical record, less than 1,000 are in common usage today. A much higher number of logographs are maintained in personal names, in particular last names, of which there are relatively few in modern Mák’ai. Logographs are otherwise commonly used in shorthand or in signs, such as the character TBD, which is usually used to indicate a grocery store or supermarket. School children in Mák’ai are taught the most common characters in school, but are typically not taught enough to be able to exclusively write using logographs. A few common logographs are given below (hover to see the translation):

3. Alternative romanisations

Mák’ai-wa also has a number of alternative romanisations. The most common of these is given below, and is predominantly used in cases where it is difficult to type diacritics:

- Tones may be written as double letters - 'á' as aa, 'í' as ii, and 'ú' as uu.

- Laminals may be written with a 'h' rather than a subscript acute accent - 't̗' as th, 'd̗' as dh, 'l̗' as lh, and 'n̗' as nh.

- The trilled 'r' is written in some transcriptions as rh, thereby representing the trill as part of the laminal series, or in others as rr.

- Ejectives are written as double letters - k' as kk, t' as tt, and t̗' as tth.

As an example, compare the following two transcriptions of the Lord's prayer (see below) in standard romanisation and in the alternate romanisation that avoids diacritics:

|

át̗á-a tai-áyú nga mk'angán raguyán juŗ-wa nga laingán túnangayí pákuyí t̗'ur̗gín-d̗al̗a nga laingán baranangayí d̗ai l̗ámúgai-a nga laingán úr̗t̗á-d̗ar, t̗ak tai-áyú |

aathaa-a tai-aayuu nga mkkangaan raguyaan jurr-wa nga laingaan tuunangayii paakuyii tthurrgiin-dhalha nga laingaan baranangayii dhai lhaamuugai-a nga laingaan uurrthaa-dhar, thak tai-aayuu |

Grammar

- Main article: Grammar of Mák’ai.

1. Verbs

1.1 Basic structure

All basic sentences in Mák’ai-wa contain an obligatory auxiliary verb, which is the main inflected verb in the sentence, as well as a typically unconjugated lexical verb. In an unmarked sentence, the auxiliary is sentence-initial and is followed immediately by the lexical verb. The auxiliary verb is polysynthetic and is the most morphologically complex aspect of Mák’ai-wa grammar.

The auxiliary verb is, at a minimum, conjugated to encode information about the grammatical subject, object (if present), tense/aspect, and evidentiality. Person agreement with the subject and object is typically such that a separate subject or object pronoun is not required. As such, the most basic sentence in Mák’ai-wa can consist of simply an auxiliary and lexical verb. Additionally, the auxiliary verb may also encode information about grammatical mood,evidentiality, and qualifiers. Noun incorporation is also common place and is used to refer to a generic nominal object.

To summarise, the auxiliary verb can contain the following grammatical components, strictly in the following order. Optional components are given in brackets.

| Subject pronoun OR (Causative + causer pronoun[1]) |

(Direct object pronoun) OR (Incorporated noun/adjective) |

(Indirect object pronoun) OR (Applicative + benefactor pronoun) |

(Adverb qualifier) | Tense/aspect | (Mood marker) | Evidentiality marker |

Given this, the most complex auxiliary verbs in Mák’ai-wa can therefore consist of up to nine individual components. The following example illustrates the maximum possible complexity of Mák’ai polysynthetic auxiliary verbs:

Ex. 1.1.1. Yangak’awun̗uluyarálurmaugaí ayaYa-nga-k’a-wu-n̗ulu-yará-lur-ma-ugaí

CAUS-1.SG.NOM.MASC-2.SG.ACC.MASC/FEM-APPL-3.SG.DAT.PROX.MASC/FEM-almost-PST.PERF-COND-INDIR.UNREP

aya

cook

'it appears that I could have almost made you cook for him'

Contrastingly, an example of the most basic sentence in Mák’ai-wa is as followsː

This sentence consists of two parts. The lexical verb, palí, simply conveys the meaning 'see'. The auxiliary verb, ngák'an, consists of three parts - the final tense/aspect root n, which denotes a present action, the initial subject prefix ngá-, which denotes a first person singular nominative subject of the Márduk gender, and the medial object prefix k'a-, which denotes a second person singular accusative object. As the auxiliary already conveys information about the subject and object, separate subject and object pronouns are not required.

In the case where a specific noun is used for the subject, the auxiliary verb must agree with the subject in both person, number, and case. For exampleː

Ex. 1.1.3. Nguk'an palí Mák’ai-paNgu-k'a-n

3.SG.NOM.PROX.MASC-2.SG.ACC.MASC/FEM-PRES

palí

see

Mák’ai-pa

Mák’ai-CLːMASC.NOM

'The nearby (Mák’ai) man sees you (non-T̗’úkai).'

This also applies when one wishes to specify the object but not the subject. For example:

Ex. 1.1.4. Ngák'un palí Mák’ai-pakNgá-k'u-n

1.SG.NOM.FEM-3.SG.ACC.PROX.MASC/FEM-PRES

palí

see

Mák’ai-pa-k

Mák’ai-CLːMASC.ACC

'I (Márduk) see the nearby (Mák’ai) man'

Both may simultaneously be done simultaneously to specify a particular subject and object. For example:

Ex. 1.1.5. Nguk'un palí Mák’ai-pa Mák’ai-pakNgu-k'u-n

3.SG.NOM.PROX.MASC-3.SG.ACC.PROX.MASC/FEM-PRES

palí

see

Mák’ai-pa

ák’ai-CLːMASC.NOM

Mák’ai-pa-k

Mák’ai-CLːMASC.ACC

'The nearby (Mák’ai) man) see the (other) nearby (Mák’ai) man'

In example 1.1.5 above, omitting the nouns following the verb will produce the less specific meaning 'he (nearby) sees him (nearby)'. As such, it is usually unnecessary to add the noun outside of the verb unless introducing a new actor in a sentence.

The maximum number of arguments which can be incorporated into an auxiliary verb is three, typically for ditransitive verbs or by using valence-increasing processes to transitive verbs (see Mák’ai language#Applicatives and Mák’ai language#Causatives below). An example of a sentence using three incorporated arguments is as follows:

Ex. 1.1.6. Kúngnur̗úgun̗ulul púkú mpalá-yun̗uKúngnu-r̗úgu-n̗ulu-l

3.DU.NOM.PROX.MASC-bread-3.SG.DAT.PROX.MASC/FEM-PST

púkú

give

mpalá-yun̗u

child-NC:FEM.SG.DAT

'those two nearby men gave some bread to the nearby girl'

1.2 Incorporation

Mák’ai exhibits incorporation, wherein the slot normally occupied by a direct object pronoun can be replaced by a noun, adjective, or location. Noun incorporation occurs when the speaker wishes to form an indefinite construction, as specifying any kind of noun outside of the axuiliary verb necessitates that that noun be definite. In other words, if a noun is incorporated, it translates to as 'an X' or 'some X', whereas if it is external to the auxiliary verb it may translate to 'the X'. To illustrate this, consider the following sentence, which includes a specified (unincorporated) noun:

Ex. 1.2.1. Ngárul n̗ígu kábá-nakNgá-ru-l

1.SG.NOM.FEM-3.SG.ACC.PROX.INANIM-PST

n̗ígu

buy

kábá-nak

bed-CLːtool.ACC

'I (Márduk) bought the (nearby) bed'

To create the indefinite meaning 'I bought a bed', as opposed to 'I bought the bed', we can incorporate the generic noun kábá in the place of the object pronoun, as in the following example:

Ex. 1.2.2. Ngákábál n̗íguNgá-kábá-l

1.SG.NOM.FEM-bed-PST

n̗ígu

buy

'I (Márduk) bought a bed'

It is important to note that noun incorporation in Mák’ai can only occur for a particular set of nouns (typically concrete objects) and never for the subject. Furthermore, only the head noun can ever be incorporated into the verb. If the incorporated noun is modified in any way, the modification must be included in a separate clause in most cases, as in the following example:

Ex. 1.2.3. Ngákábál n̗ígu, lákíd̗ímakul márNgá-kábá-l

1.SG.NOM.FEM-bed-PST

n̗ígu,

buy,

lá-kíd̗ímak-ul

3.SG.ERG.INANIM-comfortable-PST

már

very

'I (Márduk) bought a very comfortable bed' (lit. 'I (Márduk) bought a bed, it was very comfortable').

If special emphasis needs to be placed on the attribute to the incorporated noun, then the modifier may be placed after the incorporated noun's classifier, as in the following example:

Ex. 1.2.4. Ngákábál n̗ígu nak kíd̗ímak márNgá-kábá-l

1.SG.NOM.FEM-bed-PST

n̗ígu

buy

nak

NC:tool.ACC

kíd̗ímak

comfortable

már

very

'I (Márduk) bought a very comfortable bed'

Incorporation of adjectives and location phrases can also occur, but only in the context of subject-predicate compounds (such as 'I am tall' or 'she is at the beach' in English). In both of these cases, the attributive phrase is simply incorporated into the auxiliary in the place of an object, including any classifiers if necessary. Any further modifiers are simply included after the auxiliary as if the auxiliary was the head of the adjective/location phrase. The following two examples illustrate this:

Ex. 1.2.5. Tánguyanáiyun ń̗gut̗íwuTángu-yanái-yu-n

3.SG.NOM.DIST.MASC/FEM-doctor-NC:FEM.NOM-PRES

ń̗gut̗íwu

renowned

'he/she is a renowned doctor'

Ex. 1.2.6. Gangdar̗anaran múk'ulu k'igá-nal̗aGang-dar̗a-nar-an

3.DU.ERG.DIST.INANIM-table-NC:tool.LOC-PRES

múk'ulu

old

k'igá-nal̗a

book-NC:tool.ERG

'those two (distant) books are on the old table'

1.3 Pronouns and pronoun incorporation

Pronominal forms used in verbs form very complicated paradigms with several categories. These include case (nominative/accusative or ergative/absolutive depending on the agents involved, or dative for indirect objects, see Mák’ai language#Case below), person (first, second, and third), number (singular, dual, and plural), exclusivity (inclusive or exclusive, for first person only), proximity (proximal or distal, for third person only), animacy (inanimate and animate), and gender (for each of the three Mák’ai genders, as a subcategorisation of animate pronouns). Historically Mák’ai also had five separate pronoun paradigms according to which part of the body the movement involved, however, this system is no longer fully functional in modern Mák’ai. Many irregular pronominal forms are derived from this earlier five-type system. A typical example of a pronoun declension chart is given on the left for the nominative case. For a full list of pronouns, see Mák’ai language/Lexicon.

These pronominal forms may also be used externally to the verb with the suffix -ngán. In these cases, the reduplication of the pronoun serves to emphasise the pronoun, and is therefore only done under particular discourse conditions. An example of this is as follows:

Ex. 1.3.1. Tánguk'ulka palí? - R̗u, tángut'úl palí t'úngántángu-k'u-l-ka

3.SG.NOM.DIST.MASC/FEM-3.SG.ACC.PROX.MASC/FEM-PST-INTER

palí?

see

-

-

r̗u,

no

tángu-t'ú-l

3.SG.NOM.DIST.MASC/FEM-3.SG.ACC.DIST.MASC/FEM-PST

palí

see

t'ú-ngán

3.SG.ACC.DIST.MASC/FEM-PRO

'did he see him?' - 'no, he saw him (where the second 'him' refers to a different person standing further away)'

In the above example, the independent pronoun t'úngán is only used outside of the verb to emphasise that it was another person the subject saw rather than the one initially supposed in the question.

1.4 Adverb incorporation

Auxiliary verbs in Mák’ai-wa can also incorporate up to one qualifying adverb that indicates the extent to which the action was completed. Eligible adverbs for incorporation include certain temporal adverbs ('already', 'yet') and degree adverbs ('almost', 'somewhat'). Other adverbs cannot be incorporated into the verb and must be used separately after the auxiliary verb. An example of adverb incorporation in Mák’ai is as follows:

Ex. 1.4.1. Jágun̗jíyarálur ayaJá-gun̗jí-yará-lur

3.PL.NOM.DIST.NEUT-meat-almost-PST.PERF

aya

cook

'those distant T̗’úkai have almost finished cooking the meat'

1.5 Tense and Aspect

Mák’ai verbs also conjugate according to tense and aspect. Mák’ai has three main tenses, which are given below:

- l - past tense, ie, ngak'al palí, 'I saw you'

- n - present tense, ie, ngak'an palí, 'I see you'

- r̗ - future tense, ie, ngak'ar̗ palí, 'I will see you'

Note that these affixes sometimes exhibit allomorphic variation when the preceding segments end in a consonant or a diphthong. In these cases a vowel, usually 'u', is inserted before the affix, as in kúngwatágáiul palí, 'those nearby men saw those far-away women'.

Mák’ai also has an additional affix -ai which may be used after the past tense or future tense marker to indicate an event in the distant past or future. For example,:

- ngak'alai palí - 'I saw you (long ago)'

- ngak'ar̗ai palí - 'I will see you (far in the future)'

Typically, the -ai affix is used in literary or story-telling contexts, or for hyperbole in everyday speech.

Mák’ai also employs a distinction between perfective and imperfective aspect. The default form of a verb is imperfective and implies that an action is ongoing or uncompleted. The perfective form is created by using one of the following affixes instead of the above forms in the past or future tense:

- lur - past perfective.

- na - future perfective.

The perfective aspect is used to view an action as a completed whole, as opposed to being ongoing/uncompleted. Examples of the differences between the imperfective and perfective aspect in Mák’ai are given below:

Ex. 1.5.1. Ngalul párlaNga-lu-l

1.SG.NOM.MASC-2.SG.ACC.NEUT-PST.IMPERF

párla

call.for

'I (Márduk) called for you (T̗’úkai) (and there was no result)'

Ex. 1.5.2. Ngalulur párlaNga-lu-lur

1.SG.NOM.MASC-2.SG.ACC.NEUT-PST.PERF

párla

call.for

'I (Márduk) called for you (T̗’úkai) (and there was a result, ie, you answered)'

Example 1.5.1 above uses the imperfective aspect, and therefore describes the action as having been ongoing or uncompleted. The emphasis in this example is on the action in general as occurring without any particular result or outcome - that is, 'I was calling for you'. Example 1.4.2 uses the perfective aspect, and therefore focuses on the result of the action. Here, there is an implication that something came out of the speaker calling for his interlocutor - ie, the interlocutor answered him, etc.

Other more subtle distinctions in aspect can also be produced in Mák’ai by using various other linguistic processes. For example, the progressive is formed through reduplication of the lexical verb, as in example 1.5.3 below:

Ex. 1.5.3. Nugun̗jír̗ r̗ákí aya-ayaNu-gun̗jí-r̗

1.SG.NOM.NEUT-meat-FUT

r̗ákí

soon

aya-aya

cook-cook

'I (T̗’úkai) will be cooking some meat soon'

1.6 Mood

Mood in Mák’ai is indiciated by the use of affixes on the auxiliary verb. A lack of any explicit affix automatically implies the indicative mood. There are six irrealis moods that are communicated through the use of affixes. The first of these is -ma, which marks the conditional mood. -ma is used when the event described is dependent on another condition - that is, it can only be realised if something else happens. This is roughly translated with 'would' or 'could' in English. For example:

Ex. 1.6.1. Gánai d̗a laid̗arlur Mk'áit̗ar̗-d̗ar lait'úlurma palí t̗'ur̗-pakGánai

when

d̗a

POSS.ALIEN

lai-d̗ar-lur

2.SG.NOM.NEUT-NC:space.LOC-PST.PERF

Mk'áit̗ar̗-d̗ar

Mk'áit̗ar̗-NC:space.LOC

lai-t'ú-lur-ma

2.SG.NOM.NEUT-3.SG.ACC.DIST.MASC/FEM-PST.PERF-COND

palí

see

t̗'ur̗-pak

king-NC:MASC.SG.ACC

'you (T̗’úkai) could have seen the king when you were in Mk'áit̗ar'

The affix -ngayí is used to mark the optative mood. -ngayí is used when the event described is hoped, expected, awaited, or desired/wished by the speaker. Usually it is used to express that the speaker wants something to be a certain way, but it isn't. For example:

Ex. 1.6.2. Gánai d̗a laid̗arlur Mk'áit̗ar̗-d̗ar lait'úlurngayí palí t̗'ur̗-pakGánai

when

d̗a

POSS.ALIEN

lai-d̗ar-lur

2.SG.NOM.NEUT-NC:space.LOC-PST.PERF

Mk'áit̗ar̗-d̗ar

Mk'áit̗ar̗-NC:space.LOC

lai-t'ú-lur-ngayí

2.SG.NOM.NEUT-3.SG.ACC.DIST.MASC/FEM-PST.PERF-OPT

palí

see

t̗'ur̗-pak

king-NC:MASC.SG.ACC

'you (T̗’úkai) had hoped to have seen the king when you were in Mk'áit̗ar'

The affix -baru is used to mark the necessitative mood. -baru is used when the event described is necessary but not necessarily desired, when an event is destined to be, or when the event has been predetermined or prescribed. The necessitative is roughly translatable as "to be to" in English. For example:

Ex. 1.6.3. Gánai d̗a laid̗arlur Mk'áit̗ar̗-d̗ar lait'úlurbaru palí t̗'ur̗-pakGánai

when

d̗a

POSS.ALIEN

lai-d̗ar-lur

2.SG.NOM.NEUT-NC:space.LOC-PST.PERF

Mk'áit̗ar̗-d̗ar

Mk'áit̗ar̗-NC:space.LOC

lai-t'ú-lur-baru

2.SG.NOM.NEUT-3.SG.ACC.DIST.MASC/FEM-PST.PERF-NEC

palí

see

t̗'ur̗-pak

king-NC:MASC.SG.ACC

'you (T̗’úkai) were to see the king when you were in Mk'áit̗ar'

The affix -tak is used to mark the potential mood. -tak is used when the event described is considered probable or likely to occur. For example:

Ex. 1.6.4. Gánai d̗a laid̗arna Mk'áit̗ar̗-d̗ar lait'únatak palí t̗'ur̗-pakGánai

when

d̗a

POSS.ALIEN

lai-d̗ar-na

2.SG.NOM.NEUT-NC:space.LOC-FUT.PERF

Mk'áit̗ar̗-d̗ar

Mk'áit̗ar̗-NC:space.LOC

lai-t'ú-na-tak

2.SG.NOM.NEUT-3.SG.ACC.DIST.MASC/FEM-FUT.PERF-POT

palí

see

t̗'ur̗-pak

king-NC:MASC.SG.ACC

'you (T̗’úkai) will probably see the king when you are in Mk'áit̗ar'

The affix -ji is used to mark the dubitative mood. -ji is used when the event described is uncertain, doubtful, or dubious. For example:

Ex. 1.6.5. Gánai d̗a laid̗arna Mk'áit̗ar̗-d̗ar lait'únaji palí t̗'ur̗-pakGánai

when

d̗a

POSS.ALIEN

lai-d̗ar-na

2.SG.NOM.NEUT-NC:space.LOC-FUT.PERF

Mk'áit̗ar̗-d̗ar

Mk'áit̗ar̗-NC:space.LOC

lai-t'ú-na-ji

2.SG.NOM.NEUT-3.SG.ACC.DIST.MASC/FEM-FUT.PERF-DUB

palí

see

t̗'ur̗-pak

king-NC:MASC.SG.ACC

'you (T̗’úkai) might see the king when you are in Mk'áit̗ar (although it is unlikely)'

The affix -bu is used to mark the imperative mood. -bu is used when the event is directly ordered or requested by the speaker. It may also be used to express desires or to plead. For example:

Ex. 1.6.6. Gánai d̗a laid̗arna Mk'áit̗ar̗-d̗ar lait'únabu palí t̗'ur̗-pakGánai

when

d̗a

POSS.ALIEN

lai-d̗ar-na

2.SG.NOM.NEUT-NC:space.LOC-FUT.PERF

Mk'áit̗ar̗-d̗ar

Mk'áit̗ar̗-NC:space.LOC

lai-t'ú-na-bu

2.SG.NOM.NEUT-3.SG.ACC.DIST.MASC/FEM-FUT.PERF-IMP

palí

see

t̗'ur̗-pak

king-NC:MASC.SG.ACC

'(you (T̗’úkai)) see the king when you are in Mk'áit̗ar'

1.7 Evidentiality

Mák’ai verbs also contain information about evidentiality - that is, what the source of the information given in the statement is. Strictly speaking, Mák’ai distinguishes between indirectivity rather than evidentiality, in that a distinction is made between whether there is a source for the statement or not, but not as to what the source itself is. Modern Mák’ai has a three-way distinction between different kinds of evidential marking - direct, reported indirect, and unreported indirect. The direct form is unmarked and implies that the information is being reported directly - that is, that there is some kind of evidence for it. It focuses on the fact of the statement as an event. Contrastingly, the indirect forms focus on the recipient of the information by the speaker, rather than the factualness of the information itself. This is seen in the following examples:

Ex. 1.7.1. Mk'árlul palíMk'ár-lu-l

1.PL.EXCL.NOM.FEM-2.SG.ACC.NEUT-PST.IMPERF

palí

see

'we Márduk (not you) saw them (T̗’úkai) (direct)'

Example 1.7.1 above is unmarked and therefore shows direct information, focusing on the event that occurred. Example 1.7.2 below is marked with unreported indirect marking. As such, the focus is not on the actual event that actually occurred, but rather on the speaker's reception of the knowledge of the event.

Ex. 1.7.2. Mk'árluluk palíMk'ár-lu-l-uk

1.PL.EXCL.NOM.FEM-2.SG.ACC.NEUT-PST.IMPERF-INDIR.UNREP

palí

see

'allegedly, we Márduk (not you) saw them (T̗’úkai)'

Mák’ai further distinguishes two types of indirect marking - reported and unreported (or non-reported in some sources). Reported indirect marking focuses on the reception of information through a secondary source - ie, one which 'reports' the event to the speaker. This could be through hearsay, writing, or rumour, for example. The reported indirect marking is also used in quotative contexts, where the speaker is reporting someone else's speech. Non-reported indirect marking instead focuses on the reception of information through perception - ie, by witnessing or observing the event. Example 1.7.2 above uses the reported indirect marking -uk. Example 1.7.3 below conversely uses the non-reported indirect marking -ugaí:

Ex. 1.7.3. Mk'árlulugaí palíMk'ár-lu-l-ugaí

1.PL.EXCL.NOM.FEM-2.SG.ACC.NEUT-PST.IMPERF-INDIR.REP

palí

see

'it appears that we Márduk (not you) saw them (T̗’úkai)'

The non-reported indirect marking can also be used to show inference. Hence, 1.7.3 above could also be translated as 'as far as we understand, we Márduk (not you) saw them (T̗’úkai)'.

The differences between these three different evidentials are summarised in the table below:

| Indirectivity type | Meaning | Marking | Example | Possible translations | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct | A stated fact, focus is on the information itself | n/a (unmarked) | ngák'al palí | 'I saw you' | |

| Indirect | Reported/Quotative | Focuses on the reception of the information by the speaker via a secondary source (ie, it is reported to the speaker). Also used for quoted speech. | -uk | ngák'al-uk palí | 'I allegedly saw you', 'I reportedly saw you', 'they said that I saw you', etc. |

| Non-reported/Inferential/Experiential | Focuses on the speaker's experience of receiving the information through perception or inference. | -ugaí | ngák'al-ugaí palí | 'it appears that I saw you', 'I saw you (with my own eyes)', 'one could see that I saw you', etc. | |

2. Nouns

2.1 Noun classes and case

Nouns in Mák’ai are marked for case, gender, and number, but not definiteness. Both case and gender are marked through the use of post-nominal classifiers, of which there are thirteen. Classifier use is obligatory, but the assignment of a particular noun to a set noun class is not determined. Rather, the choice of classifier used reflects the exact way the object is used. For example, the classifier mú is used for nouns belonging to the vegetation class, as in átá-mú, 'stick'. Conversely, the classifier na is used for nouns belonging to the tool class. The classifier na can therefore be used with átá to form átá-na, with the new meaning of 'stick as a tool', rather than 'stick as a stick' (ie, a branch used as a walking stick, etc.). In this way, classifier membership is not fixed, but fluid depending on the way the object is used.

Mák’ai has eight cases - nominative/ergative, accusative/absolutive, dative, genitive, instrumental, and locative. Mák’ai also exhibits split-system ergativity, meaning that the choice between nominative/accusative marking and ergative/absolutive marking depends on the particular context of a sentence. This is explained further below in Mák’ai language#Split-system ergativity. A full table illustrating the declension of noun classifiers for case is included below:

| Case | pa (ngárduk[5]) |

yu (márduk[6]) |

ja (t̗'úkai[7]) |

kí (non-Mák’ai person, most animals) |

a (spirit, deity) |

mú (plant matter) |

n̗i (food, edible substances) |

na (tool, weapon) |

gu (fire, heat) |

wa (language, sounds) |

wá (water, aquatic animals) |

d̗a (time and space) |

ngu (generic) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nominative | pa | yu | ja | kí | a | mú | n̗i | na | gu | wa | wá | d̗a | ngu |

| Absolutive | pa | yu | ja | kí | a | mú | n̗i | na | gu | wa | wá | d̗a | ngu |

| Accusative | pak | yuk | jak | kíyak | á | múk | n̗ik | nak | guk | wak | wák | d̗ak | ngut̗ak |

| Ergative | pal̗a | yul̗a | jal̗a | kíl̗a | ar | múl̗a | n̗il̗a | nal̗a | gul̗a | wal̗a | wál̗a | d̗al̗a | ngul̗a |

| Dative | pan̗u | yun̗u | jan̗u | kín̗u | án̗ | mún̗u | n̗in̗u | nan̗u | gun̗u | wan̗u | wán̗u | d̗an̗u | ngun̗ |

| Genitive | par | yur | jur | kír | áyú | múr | n̗ir | nar | gur | war | wár | d̗ar | ngur |

| Instrumental | pawá | yuwá | jawá | kíwá | áwá | múwá | n̗iwá | na | guwá | wawá | wáwá | d̗awá | nguwá |

| Locative | par | yuú | jur | kír | áyú | múr | n̗ir | nar | guú | war | wár | d̗ar | nguú |

2.2 Number

Mák’ai has three numbers - singular, dual, and plural - which are reflected in both its pronominal system and its noun declension. Singular nouns are unmarked while dual and plural nouns take an additional suffix on to the noun's classifier. Typically, dual is indicated by affixing -n̗ and plural by affixing -r to the end of the noun classifier where the noun classifier ends in a vowel. For example, consider the following:

- mpalá-pa - boy-NC:MASC.NOM.SG - 'a boy'

- mpalá-pan̗ - boy-NC:MASC.NOM.DU - 'two boys'

- mpalá-par - boy-NC:MASC.NOM.PL - 'boys'

Note, however, that there are many exceptions to this rule, and that this rule does not apply where the classifier ends in a consonant. The following charts therefore show the form of classifiers in the dual and plural forms respectively.

| Case | pa (ngárduk) |

yu (márduk) |

ja (t̗'úkai) |

kí (non-Mák’ai person, most animals) |

a (spirit, deity) |

mú (plant matter) |

n̗i (food, edible substances) |

na (tool, weapon) |

gu (fire, heat) |

wa (language, sounds) |

wá (water, aquatic animals) |

d̗a (time and space) |

ngu (generic) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nominative | pan̗ | yun̗ | jan̗ | kín̗ | an̗ | mún̗ | n̗in̗ | nan̗ | gun̗ | wan̗ | wán̗ | d̗an̗ | ngun̗ |

| Absolutive | pan̗ | yun̗ | jan̗ | kín̗ | an̗ | mún̗ | n̗in̗ | nan̗ | gun̗ | wan̗ | wán̗ | d̗an̗ | ngun̗ |

| Accusative | pan̗ak | yun̗ak | jan̗ak | kín̗ak | án̗ | mún̗ak | n̗in̗ak | nan̗ak | gun̗ak | wan̗ak | wán̗ak | d̗an̗ak | ngun̗ak |

| Ergative | pan̗l̗a | yun̗l̗a | jan̗l̗a | kín̗l̗a | aran̗ | mún̗l̗a | n̗in̗l̗a | nan̗l̗a | gun̗l̗a | wan̗l̗a | wán̗l̗a | d̗an̗l̗a | ngun̗l̗a |

| Dative | pan̗un̗ | yun̗un̗ | jan̗un̗ | kín̗un̗ | n̗án̗ | mún̗un̗ | n̗in̗un̗ | nan̗un̗ | gun̗un̗ | wan̗un̗ | wán̗un̗ | d̗an̗un̗ | ngun̗u |

| Genitive | pan̗ar | yun̗ur | jun̗ur | kín̗ir | áyún̗ | mún̗ur | n̗in̗ir | nan̗ar | gun̗ur | wan̗ar | wán̗ar | d̗an̗ar | ngun̗ur |

| Instrumental | pan̗wá | yun̗wá | jan̗wá | kín̗wá | án̗wá | mún̗wá | n̗in̗wá | nan̗ | gun̗wá | wan̗wá | wán̗wá | d̗an̗wá | ngun̗wá |

| Locative | pan̗ar | yun̗ú | jun̗ur | kín̗ir | áyún̗ | mún̗ur | n̗in̗ir | nan̗ar | gun̗ú | wan̗ar | wán̗ar | d̗an̗ar | ngun̗ú |

| Case | pa (ngárduk) |

yu (márduk) |

ja (t̗'úkai) |

kí (non-Mák’ai person, most animals) |

a (spirit, deity) |

mú (plant matter) |

n̗i (food, edible substances) |

na (tool, weapon) |

gu (fire, heat) |

wa (language, sounds) |

wá (water, aquatic animals) |

d̗a (time and space) |

ngu (generic) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nominative | par | yur | jar | kír | ar | múr | n̗ir | nar | gur | war | wár | d̗ar | ngur |

| Absolutive | par | yur | jar | kkír | ar | múr | n̗ir | nar | gur | war | wár | d̗ar | ngur |

| Accusative | parak | yurak | jarak | kírak | ár | múrak | n̗irak | narak | gurak | warak | wárak | d̗arak | ngurak |

| Ergative | parl̗a | yurl̗a | jarl̗a | kírla | l̗ur | múrl̗a | n̗irl̗a | narl̗a | gurl̗a | warl̗a | wárl̗a | d̗arl̗a | ngurl̗a |