Mák’ai

This article or section is in the process of an expansion or major restructuring. You are welcome to assist in its construction by editing it as well. If this article or section has not been edited in several days, please remove this template. If you are the editor who added this template and you are actively editing, please be sure to replace this template with {{in use}} during the active editing session. Click on the link for template parameters to use.

This article was last edited by Javants (talk | contribs). (Update) |

Commonwealth of Mák’ai | |

|---|---|

|

Motto: Ga bagair̗ jákang luk'í-parak ga "Our hands shall not be tied" | |

| |

| Capital and largest city | Mk'ái-t̗ir̗ |

| Official languages | Mák’ai-wa |

| Ethnic groups (2022) |

|

| Demonym(s) | Mák’ai |

| Government | Semi-representative autocratic T'aganate |

| Mar̗uk Ngátaikángán K’úr̗ai | |

| Ak'ání Rungpalíguk R̗akí | |

| Mwáni Luk'urt̗íwunggáwa Máyár | |

| Legislature | Houses of Mák’ai |

| House of the Commonwealth | |

| House of Unions | |

| Formation | |

• Ascension of the Sun | 0.rk |

• Makai Vbarkîn | 1.ak |

• Mák’ai-gu Yúbá | 66.tk |

• New T'aganate | 436.tk |

| Area | |

• Total | 635,133 km2 (245,226 sq mi) (68th) |

• Water (%) | 3.2 |

| Population | |

• 2022 estimate | 41,682,419 |

• 2020 census | 41,648,106 |

• Density | 65.6/km2 (169.9/sq mi) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2022 estimate |

• Total | $1,005,692,831 |

• Per capita | $24,128 |

| Gini (2020) |

medium |

| HDI (2022) |

very high |

| Currency | Mák’ai T'ula (₮) (MTL) |

| Date format | dd-mm-yyyy |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | TBD |

| ISO 3166 code | MK |

| Internet TLD | .mk |

- This article is part of Project Exodus.

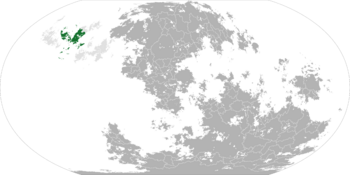

Mák’ai, officially the Mák’ai Commonwealth (Mák’ai-wa: Nbátalak-la Mák’ai, IPA: /n̠bɐ́t̠ɐ̀l̠ɐ̀kl̠ɐ̀ mɐ́kʼɐ̀ɪ/; Kto: Ktanoû az Makai) or the Mák’ai T'aganate (Mák’ai-wa: T'agan-la Mák’ai, Kto: Tagandai az Makai), sometimes alternatively anglicised as Mak’ai, Makai, or Maakkai, is a sovereign state located primarily on the island of Makaigan in central Ejawe, in the north-west of the continent of Aicho on the planet Sabel. It is the world's 68th largest country with a size of 635,133 square kilometres, putting it behind TBD but ahead of TBD. It shares a land border with the Ktoic Confederacy to the north, and maritime borders with Nga to the east, Hakkhai to the south, Mtasai and Imai to the west, and Raa to the north-west. Mák’ai has an estimated population of 41,682,419 as of 475.tk and is an insular nation with a predominantly humid subtropical and humid continental climate. The capital and largest city is Mk'ái-t̗ir̗, with other major cities including Kut̗ú Jar̗ar, R̗adúr Numir, Út̗ir̗, Numur Bárkín, and Gabán̗.

Etymology

The name Mák’ai is an archaic form of the word for 'people' in the Mák’ai-wa language, itself being the dominant language of Mák’ai. In turn, Mák’ai comes from the Proto-Pan-Ejawan word *mahkeys (IPA: /maʔkejs/), with the meaning of person. This is in turn related to the endonym Mtasai for the Mtasai people of western Ejawe, coming from Proto-Raa-Makaiganic*metahkeysey (IPA: /metaʔkejsej/), 'western people'. *Mahkeys can be further traced back to the Proto-Pan-Ejawan *ham!akteyz (IPA: /hamk͡!aktejz/), which also meant 'people'.

The political entity of Mák’ai has had many different names over its history. In general, however, the term Mák’ai-la is used to refer to the region of Mák’ai influence, with the nominal classifier '-la' indicating 'the region of Mák’ai'. In the current day, Mák’ai is referred to officially as the Mák’ai Commonwealth, or Nbátalak-la Mák’ai. 'Commonwealth' here comes from a direct translation of the Mák’ai-wa word Nbátalak, a compound consisting of nbá, 'good', and talak, 'common'. Alternatively, Mák’ai is also known as the Mák’ai T'aganate, a T'aganate being a state headed by a T'agan. The noun T'agan has its origin in the Proto-Pan-Ejawan word *s'daghn (IPA: /sˀdɑɣn/), which referred to the head of the body.

In other Ejawan languages, Mák’ai is known as Makai (Kto and Imai), Makaizari (Ktazari), Mäkkai (Kai), and Mbakai (Mtasai). Mbakai translates more literally as 'eastern people', and is the common name of Mák’ai in many western Ejawan states.

History

- Main article: History of Mák’ai. For information on Mák’ai timekeeping, see Numur̗ian calendar.

Prehistory (before 1300.mk)

- See also: Prehistory of Ejawe.

What is now Mák’ai was first settled by anatomically modern humans some 30-40,000 years ago by a group known as the Paleo-Ejawan people, now believed to have initially migrated from mainland Aicho by crossing the Azwanic landbridge. Very little is known about the history of these Paleo-Ejawan people as a result of a lack of archaeological evidence, and in particular their later displacement by the Proto-Ejawan people, who themselves form the ancestors of modern-day Mák’ai people. The Paleo-Ejawan people likely lived a nomadic hunter-gatherer lifestyle, and remained in central Mák’ai for several thousand years. By approximately 14000.mk, however, a second wave of emigration out of Aicho led to the arrival of the Proto-Ejawan people in Ejawe, who initially settled in what is now south-western Azwan. These Proto-Ejawan people later split into a number of cultural and linguistic subgroups, one of which, now known as the Lash Mawq'ayy culture, migrated from northern Hakkhai across the Sea of Nga, landing in what is now south-eastern Makaigan. These would be the first modern Ejawan people to arrive in modern-day Mák’ai, and would soon settle across much of the country.

Little is known of the ultimate destiny of the earlier Paleo-Ejawan peoples whom the Lash Mawq'ayy displaced, but it is certain that they had largely disappeared in the Mák’ai heartlands by 12000.mk. By this point, the Lash Mawq'ayy culture had diversified into a number of distinctive daughter cultures, including most notably the Varkîn culture of south-eastern Kto, the Nangasi culture of central Nungái-la, and the Mawk'i culture of central Makaigan. This latter culture was the ancestor of the later Mák’ai people around whom the modern Mák’ai state would form, but for many thousands of years they continued to remain largely nomadic. Agricultural communities began to emerge in the warmer eastern Makaiganic climates by 8500.mk as the early Ktoic civilisation began to emerge in the heartlands of the Kto Vbarkîn. This would form the first true civilisation in Ejawe as a region, and would be a powerful influence in the ancient history of many modern Ejawan states. These early agricultural communities began to coalesce into small city-states collectively known as the Kto Mulis ('ancient Kto' in the modern Kto language), which gradually grew in power and size over the following centuries.

Ancient Mák’ai (c. 1300.mk-1.rk)

Ancient Numur

Mák’ai historians generally refer to the period known as ‘ancient Mák’ai’ as beginning with the emergence of writing around 1300.mk in Ancient Numur (Numur̗ in Mák’ai-wa), a fertile region of eastern Makaigan roughly corresponding to the modern-day prefecture of Numur̗ái. Located between the highly fertile lands between the River It̗ar in the south and the River R̗át’ak in the north, the temperate climate of the region during the late Múrk'ulak period meant that Numur was a prime candidate for the early emergence of agriculture in Ejawe. Archaelogical evidence from the area suggests that the establishment of small agricultural communities in earlier millennia had coalesced into sizable proto-cities around agricultural centres by around 1300.mk. Of these, the most important was the city of Hrush (modern Mák’ai: R̗u) [1], located to the south-west of modern-day Numúr̗ Bárkín. It is in Hrush that the earliest form of writing in Makaigan developed – Numurian glyphs – which would later develop into Ktoic script and Mák’ai logographs. This writing, which was initially used as a kind of mathematical shorthand, quickly spread throughout south-eastern Makaigan with the expansion of Numurian society. Records from the period, most notably the Nakiman stelae found in the south-eastern city of Bas, provide the first written history of the Numurian people. These sources, among others, have led modern historians to divide the early ancient history of Mák’ai into a number of distinctive periods, typically referred to as ‘kingly dynasties’, which shaped the socio-political history of south-eastern Makaigan in the ancient era.

The first of these is known as the First Hrushak Kingly Dynasty (often abbreviated to Hrush-I, sometimes also known as the Old Numurian Kingly Dynasty). Based primarily around the largest city in ancient Numur – Hrush – the first Hrushak kingly dynasty was characterised by the emergence of an early bureaucracy facilitated through the development of writing. It was during this period that Hrush came to be the first real city in Mák’ai as a result of these agricultural and social developments. The Hrush-I period also sees evidence of ancient Mák’ai spirituality, characterised like most Ejawan religions by belief in two principle deities – the male embodiment of the Earth Thurn and the female embodiment of the Sky Thain. Central to Numurian religion of the Hrush-I period was the belief in the Royal Pair (Rak Yubas) as the manifestation of Thurn and Thain on Earth, as illustrated in the following excerpt from the stela of Hrashnamurek I:

| “ | Here lieth Hrashnamurek Thurn, son of Hrashnumasek Thurn, of the Earth and committed unto himself once more. Hereabove Amlaneki Thain, of the Sky and committed unto herself once more. Walkers in the space between as it is Right, rulers of glorious Hrush, City of Two | ” |

| — Stela of Hrashnamurek I, found near Hrush B, c. 1220.mk | ||

Interestingly, Hrush-I period Numur does not seem to exhibit the three-way gender division common to most Ejawan societies, including modern-day Mák’ai. The limited evidence of non-Hrush societies of this period seem to suggest that the third gender was an import from northern Kto, arriving with the establishment of the second major Numurian kingly dynasty of Kesh around 800.mk. The Keshak kingly dynasty (or Kesh-I), so-named for its origins from the north-eastern Numurian city of Kesh, adopted writing from Hrush and quickly developed as a more militaristic culture. Under the leadership of Maskar I, the Keshak conquered Hrush, remaining a prominent kingly dynasty in the region for several centuries.

In around 700.mk, following the death of King Kunaset Thurn, the territories of the ancient Numurian Kingdom were split among his three surviving children. The eldest continued the Kesh-I dynasty centred around Kesh (now ruins to the north of the city of K'aiyíngá), while his two younger brothers saw the emergence of rival dynasties to the north and south-west of the Numurian homelands. Eventually, the descendants of Kunaset Thurn's third son would found the Rask Kingly Dynasty, which in turn would be the predecessor of the Kingly House of Râktei - the ultimate rulers of the Kto Vbarkîn. The remainder of the Numurian period, however, saw repeated conflict, unification, and separation of various Numurian states descended from the original Kesh-I kingdom, until its ultimate collapse around 300.mk.

Numur was one of the most advanced cultures in Ejawe during the ancient period. It was markedly bureaucratic and religious, with human sacrifice being an essential part of religious life to appease the twin gods of Thurn and Thain. The following description from the Western Songs, a series of biographies of the early Kesh-I kings, is typical of Ancient Numur:

| “ | In preparation for the coronation of Ktunasetbak Thain, daughter of Ktarebak Thain, five thousand men were selected for the honour of Thurn and five thousand women for the honour of Thain. Of these numbered equal parts western slave, children of the aristocracy, soldiers, peasants, and priests. They were paraded through the streets of Hrush, bathed in the Waters[2] with sandalwood and honey, and thence taken to the Great Temple, where the High Priests made their offerings. The ten thousand were there returned to Thurn and Thain[3], as insurance of the prosperous reign of Ktunasetbak Thain, the shining of the Sun, and the flowering of the Earth. | ” |

| — From 'The Coronation of Ktunasetbak Thurn', scroll 7 of the Western Songs, c. 650.mk | ||

By 400.mk, dynastic struggles and bloody conflicts between ruling families, famine, and weak leadership led to the fragmentation of the Numurian Kingdom into a multitude of small warlord states. Control over the broader Numurian region fluctuated regularly over the subsequent centuries in the wake of political and geographic instability. Concurrently, the emergence of the northern Ktoic city states led to a shift in the regional power balance, as the influence of Numur began to fade and the cultural and political hegemony of the Ktoic city-states began to increase. By 300.mk, Ancient Numur had come to an end, with the Nine Kingdoms of the Kto Mulis coming to power.

The Kto Mulis

The Kto Vbarkîn (1.rk-1.ak)

The Makai Vbarkîn (1.ak-875.ak)

The Koi az Pser̄arh (875.ak-257.tk)

The Koi az Ktarh (257.tk-436.tk)

Kuraist Mák’ai (436.tk-present)

Geography

- Main articleː Geography of Mák’ai.

The river T̗ákan̗ in southern Kto, near the Makaiganic mountain range.

The Valley of It̗ar in southern Kto.

Typical woodland in the warmer regions of Kto.

A road in a typical agricultural area in central Kto.

A small homestead in south-central Kto.

The river Lang in northern Kto.

A typical beach in northern Kto.

A small river in Nungái-la.

Winter on the coast of northern Nungái-la.

The south-western coast of Wuk’ái-la in the Sea of Nga.

A cove on the island of Mál̗í in the southern Ejawan Sea.

Mák’ai is a principally insular nation, but it maintains a high level of geographic diversity. The majority of the country is located in the southern and central regions of the island of Makaigan, itself the third largest and most central island within the broader region of Ejawe. To the west of Makaigan lies the second largest island in Mák’ai, Nungái-la, which is separated from Makaigan by the narrow Straight of Tigers and has close ties both geographically and historically to Makaigan. The third largest island to make up Mák’ai is Wuk’ái-la, located to the south-east of Makaigan within relatively close proximity to Hakkhai. Mák’ai is further made up of several other smaller islands, generally broken up into three groups - the northern island groups of TBD and TBD, the central island groups of TBD and TBD, and the southern island group of TBD.

The geological history of Mák’ai is largely defined by the interactions between the Ejawan and south-eastern Hakkhitic tectonic plates, whose collision historically formed the Makaiganic mountain range millions of years ago, as well as the emergence of Wuk’ái-la and subsequent development of Ejawan Rift between central and southern Ejawe. This rift in turn resulted in the Kanu line, a geographical barrier that led to the diversification of Ejawan wildlife externally to mainland Aicho. Most of the islands in Mák’ai are mountainous as a result of this tectonic movement. The largest mountain range in Ejawe, the aforementioned Makaiganic mountain range, runs north-south through Makaigan, separating the warmer climactic regions of Kto-la in the east from the cooler Mák’ai heartlands to the west. The Makaiganic mountain range then stretches underwater from the southern coast of Makaigan, and its subsequent peaks form the central Mák’ai islands. Many of these islands were formerly volcanic, and as such are highly fertile. A smaller mountain range also runs north-south through the island of Nungái-la, albeit much smaller in scale to those that divide Makaigan. Outside of these mountainous regions, most of Mák’ai is, or was historically, forested. The north and west of the country in particular is dominated by vast deciduous forests, while much of the eastern coast has been cleared for agricultural use as a result of the region's warmer climate.

As an insular nation, Mák’ai's coasts and waterways have been pivotal in the nation's development. Mák’ai is surrounded by four major bodies of water - to the north, the Northern Ocean; to the west, the Straight of Bones, which separates Nungái-la from Mtasai; to the south, the Ejawan Sea; and to the east, the Sea of Nga. Mák’ai also possesses a number of short but navigable rivers, particularly in the eastern region of Kto-la, where the rivers are sourced from the Makaiganic mountain range. The longest rivers in Mák’ai are the River Mnu, which runs west-east through the island of Nungái-la, and the River T̗ákan̗, which runs south-west through southern Kto-la. These rivers are important sources of water for many of the nation's major agricultural regions and are thereby essential to the Mák’ai economy. As a result of this economic importance, many of Mák’ai's coastal regions and waterways are subject to stringent environmental protections to prevent their degradation through overuse.

Climate

- Main article: Climate of Mák’ai.

Three are three major climactic regions within Mák’ai. The eastern coast of Makaigan as well as Wuk’ái-la and the central islands all possess a humid subtropical climate, characterised by hot and humid summers with cool to mild winters. These are a result of warm oceanic currents moving through the Sea of Nga which heat the areas of Makaigan east of the Makaiganic mountains. The west of the mountains, as well as Nungái-la and the northern islands, have a humid continental climate, characterised by large seasonal differences with very cold winters as a result of cold oceanic currents flowing south from the Koburing circle. The southernmost islands in Mák’ai are characterised by a hot-summer Mediterranean climate, with hot, dry summers and mild, wet winters, primarily as a result of their greater proximity to the equator.

In general, winters in Mák’ai are relatively harsh in the north and west, although much more mild to the south and east of the Makaiganic mountain range. Snow is commonplace in these areas during winter and forms approximately 5-10% of the country's total precipitation per year. Summers tend to come slightly later than in other parts of Sabel, with the warmest months being August, July, and September. September is also the wettest month on average as warm humid conditions dominate most of Mák’ai's subtropical climactic regions. Winters are generally drier than summers although still possess a somewhat high degree of rainfall, as Mák’ai is in general a region of relatively high humidity.

| Climate data for Mák’ai | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °F | 53.2 | 51.1 | 57.7 | 66.4 | 73.8 | 79.5 | 85.3 | 88.2 | 81.3 | 73.2 | 61.7 | 53.8 | 68.7 |

| Daily mean °F | 41.5 | 41.7 | 49.1 | 58.1 | 65.8 | 72.7 | 79 | 81 | 74.8 | 65.8 | 54.9 | 46.6 | 61 |

| Average low °F | 29.8 | 32.2 | 40.3 | 49.6 | 57.7 | 65.8 | 72.7 | 73.8 | 68.2 | 58.3 | 47.8 | 39.2 | 52.5 |

| Average precipitation inches | 20.71 | 22.2 | 46.73 | 49.76 | 55.28 | 66.38 | 60.71 | 66.5 | 83.23 | 77.28 | 36.77 | 20.39 | 50.51 |

| Average high °C | 11.8 | 10.6 | 14.3 | 19.1 | 23.2 | 26.4 | 29.6 | 31.2 | 27.4 | 22.9 | 16.5 | 12.1 | 20.4 |

| Daily mean °C | 5.3 | 5.4 | 9.5 | 14.5 | 18.8 | 22.6 | 26.1 | 27.2 | 23.8 | 18.8 | 12.7 | 8.1 | 16.1 |

| Average low °C | −1.2 | 0.1 | 4.6 | 9.8 | 14.3 | 18.8 | 22.6 | 23.2 | 20.1 | 14.6 | 8.8 | 4.0 | 11.4 |

| Average precipitation cm | 52.6 | 56.4 | 118.7 | 126.4 | 140.4 | 168.6 | 154.2 | 168.9 | 211.4 | 196.3 | 93.4 | 51.8 | 128.3 |

| Source: National Bureau of Meteorology (Mk'ái-t̗ir̗) | |||||||||||||

Flora and fauna

- Main article: Flora and fauna of Mák’ai.

As a region of high climactic diversity, Mák’ai is home to some 8000 species of flora, of which approximately 40% are endemic. The north and west of Mák’ai is covered by deciduous woodlands, dominated by Ít̗’án, Málan, Kírakíra, and Makai Karaiya trees in the canopy. The understory is generally dominated by small flowering palú grasses, ferns, and temperate shrubs. Warmer areas of Mák’ai's west are also home to an incredible diversity of mosses and lichens as a result of warmer weather and high precipitation. Eastern Makaigan and the central Mák’ai islands are instead dominated by evergreen broadleaf forests as a result of the warmer climate. These forests are typically characterised by dense and layered tree cover, with the highest layers sometimes reaching heights of 20 meters or more. Typical trees in these forests include Yuyúk’a, Nguír, Áyurá, and the flowering Mlálá tree. The understory of these forests are dominated primarily by Ńt̗út̗’u trees, shrubs, and saplings, all of which are relatively shade tolerant. Many of these plants had traditional uses in ancient Mák’ai medicine or are common food sources, such as the fruit of the Ńt̗út̗’u tree. Mák’ai's southernmost islands, which possess a hot-summer Mediterranean climate, are less dominated by tall forests. Common flora in this region includes the K’ai and K'ugan trees in higher-altitude areas, fields of Ílú and Baya flowers, and low flowering ground-cover like Nggúnggan.

An Ít̗’án tree, common in northern Mák’ai.

Another typical tree in northern Mák’ai, the Málan

The Kírakíra, a widespread tree throughout Mák’ai.

Makai Karaiya, an endemic Karaiya found only in Mák’ai.

Palú grasses typical of the understory of forests in northern and western Mák’ai.

A Yuyúk’a tree, typical of the evergreen broadleaf forests of eastern Makaigan.

A 'Nguír tree, another common tree in eastern Makaigan.

An Áyurá tree, another common tree in eastern Makaigan.

The flower of the Mlálá tree, highly sort after in eastern Makaigan for its medicinal properties.

The fruits of the Ńt̗út̗’u tree, commonly eaten as a food source in eastern Makaigan.

The K’ai tree, common in some more forested areas of southern Mák’ai.

A small forest of K'ugan trees in southern Mák’ai.

A field of Ílú flowers in southern Mák’ai.

Baya flowers, common in southern Mák’ai.

Nggúnggan, a common flower plant ubiquitous throughout southern Mák’ai.

Mák’ai is also home to incredible faunal diversity. Mák’ai is an important destination for migratory birds from north-western Sazhomara, many of which uniquely migrate to Mák’ai, particularly its southern islands. Important migratory species include the Makai Kula, Red-chested Maiyabird, Great Ocean Ley, Nungai Sea-Ley, and the Southern Yellow Malarai. Mák’ai is also home to a number of non-migratory birds, and has the largest diversity of Makaibirds and Makai Honeyeaters in the world. This latter group is further characterised by its two major evolutionary subgroups - the highly colourful Orubaze Honeyeaters, also called Firebirds, found in southern Mák’ai, and the Northern Honeyeaters found further north. Characteristic species of these groups include the Blue-crowned Red Firebird, Royal Firebird, Ashen Firebird, Makaiganic Needlemouth, Yellow-shrouded Honeyeater, and the Yellow-striped Honeyeater.

Mák’ai is also home to a diverse range of mammals, including a number of endemic large carnivores. Of these, the most famous are the Ejawan Greatbear and the Makaiganic Tiger, both of which have been very important culturally to the Mák’ai people. Other smaller carnivores include the widespread Aicho fox and the Wuk'ai Mamo, itself endemic to the island of Wuk’ái-la. Other common mammals seen in Mák’ai include the Makaiganic K'aná, the Ejawan Yomolo, and a number of smaller marsupials including Sabel's only extant ratflyer, the Long-tailed Ratflyer. Mák’ai is also home to diverse species of arthropods, including the rare family of Sunspiders, known for their colourful mating displays, and the deadly Ejawan Giant Wasp. Other notable animals endemic to Mák’ai include the Ngalai Water-King, the Makai Rainbow Snake, and the Makaiganic Tigerlizard, the later of which is often exported globally as part of the pet trade. The oceans around Mák’ai are also home to the Northern Grey Whale, which, although not endemic, is commonly seen around Mák’ai.

The Red-chested Maiyabird, a migratory seabird found in southern Mák’ai.

The Makai Kula, an important migratory seabird found in southern Mák’ai.

The Great Ocean Ley, another migratory seabird found in Mák’ai.

The Nungai Sea-Ley.

The Little Makaibird, a Makaibird native to eastern Makaigan.

The Red-backed Makaibird, a striking Makaibird from the central islands of Mák’ai.

The Blue-crowned Red Firebird, native to southern Mák’ai.

The Royal Firebird, another native of southern Mák’ai.

The Ashen Firebird, also native to southern Mák’ai.

The Makaiganic Needlemouth, a species of Northern Honeyeater native to eastern Makaigan.

The Yellow-shrouded Honeyeater, another Northern Honeyeater native to western Makaigan.

The Yellow-striped Honeyeater, native to western Makaigan.

The Ejawan Greatbear, a large carnivore culturally important to the eastern Mák’ai and Kto peoples.

The Makaiganic Tiger, a tiger species endemic to Mák’ai and the country's national emblem.

A Wuk'ai Mamo, an endemic cat to the island of Wuk’ái-la.

A Makaiganic K'aná, a common grazing animal in Mák’ai.

The Ejawan Yomolo, another culturally important animal to the Mák’ai.

The Long-tailed Ratflyer, Sabel's only extant ratflyer, endemic to Mák’ai.

The Golden Sunspider, a species of Sunspider endemic to Mák’ai.

The Ejawan Giant Wasp, a deadly species of wasp endemic to Ejawe.

The Ngalai Water-King, a notable lizard species endemic to Mák’ai.

The Makai Rainbow Snake, a snake species endemic to Mák’ai and an important cultural symbol to the Kto.

The Makaiganic Tigerlizard, endemic to Mák’ai although exported globally as a pet.

A Northern Grey Whale breaching the water in the Ejawan Sea.

Politics

- Main article: Politics of Mák’ai.

|

|

| Mar̗uk Ngátaikángán K’úr̗ai K’úr̗ai Eater-of-Suns Supreme T'agan of the Commonwealth of All Mák’ai |

Ak'ání Rungpalíguk R̗akí General Secretary of the Houses of Mák’ai |

Following the end of the Mák’ai Civil War in 436.tk, Mák’ai has been formally structured as a semi-representative, autocratic, authoritarian T'aganate ruled by the Supreme T'agan of the Commonwealth of All Mák’ai (Mák’ai: T'agan R̗úwák nga Nbátalak-la Mák’ai n̗a). The current head of state is Mar̗uk Ngátaikángán K’úr̗ai, often referred to by their epithet as K’úr̗ai Mángátaikángánk'ai, or 'K’úr̗ai Eater-of-Suns', who has reigned as Supreme T'agan since the death of Rawak L̗áwur̗ítárk'unggáwa Takán in 459.tk. The Supreme T'agan holds absolute power in the Mák’ai government and is appointed as successor by the previous Supreme T'agan. The T'agan themselves must be a member of the ruling political party, which since 436.tk has been the Commonwealth of All Mák’ai (Nbátalak-ngu Mák’ai N̗a, or NMN̗).[4] At a national level, the Mák’ai government is divided into three legislative bodies. The lowest level, the House of Unions (Ḿt̗a-ngu Jugán-ngur), consists of 560 elected representatives, known as jat'aganra (lit. 'little T'agan'). Each administrative division of Mák’ai elects a different number of jat'aganra depending on its classification - 20 for each state, special administrative district, or prefecture, 25 for each autonomous region, and 5 for each territory. The various jat'aganra must then optionally align themselves with at least three of the various unions[5] (jugán-ngur singular jugán-ngu), which represent particular interest groups within Mák’ai. The role of the House of Unions is to discuss and propose potential laws, which are subsequently sent to the next highest legislative body for review - the House of the Commonwealth. The head of the House of Unions is the Secretary of the House of Unions, currently Mwáni Luk'urt̗íwunggáwa Máyár.

The House of the Commonwealth (Ḿt̗a-ngu Nbátalak-ngur) consists of 200 members, all of whom must be members of the ruling party (the NMN̗). Any member of the House of Unions is eligible to join the NMN̗ and become a member of the House of the Commonwealth, but appointment to the Party is ultimately at the discretion of higher-level Commonwealth officials. Any member of the House of Unions who joins the House of the Commonwealth must abolish all connections to existing unions in favour of representing the official Party stance, which itself is directed from the highest level of the legislature - the House of the T'agan. The House of the T'agan (Ḿt̗a-ngu T'agan-yur) is made up of the T'agan herself as well as the House of the Twelve (Ḿt̗a-ngu Mánju-n̗yur), a cabinet consisting of the T'agan and eleven ministers (t'a) appointed directly by the T'agan from the House of the Commonwealth. Second after the T'agan herself in importance is the General Secretary of the Houses of Mák’ai, currently Ak'ání Rungpalíguk R̗akí, who acts as the leader of the House of the Commonwealth and t'a in the House of the Twelve. Both the House of the Commonwealth and the House of the T'agan regulate the behaviour of the House of Unions more generally, with the consequence that the limited degree of democratic representation in the Mák’ai government is highly restricted so as to align with broader Commonwealth aims.

Mák’ai is semi-federal in that each of the administrative divisions have their own local governments with varying degrees of power. The three autonomous regions of Lá Mrúk-kír, T'ulá, and Wuk'ái-la each have their own local government with significant autonomy from the national government in Mk'ái-t̗ir̗. Local government in these three autonomous regions is regulated by nominally independent parties, which are de facto integrated directly with the NMN̗. The six Ktoic prefectures also have their own Council of Ktoic Peoples which is nominally independent of the national government, but is de facto integrated as a subcommittee of the House of the Commonwealth. Each state maintains their own smaller scale local government with limited ability to pass laws (see Law of Mák’ai). The territory of N̗t̗í-la is ruled by a small Territorial Council which is again integrated with the House of the Commonwealth. Finally, the special administrative region of Mk'ái is ruled by the special Subhouse on hte Special Administrative Division of Mk'ái, itself also a subdivision of the House of the Commonwealth.

Political organisations

- Main articles: Commonwealth of All Mák'ai, Union (Mák'ai political organisation).

Law

Administrative Divisions

- Main article: Administrative divisions of Mák’ai.

Mák’ai is divided into 28 administrative divisions collectively referred to as d̗agai-d̗ar (singular: d̗agai-d̗a), which form the highest level of subnational federal division in the country. Under the Mák’ai constitution, each of these d̗agai-d̗ar constitute a federal entity with its own local government, head (called a mik’aí in most cases), and court. While each state is subjected to federal law, each state also has its own laws and customs, and vary in the exact extent to which they individually operate.

Each of the 28 d̗agai-d̗ar are themselves divided into several subtypes. 17 of these are states or d̗uruk-d̗ár (D̗D̗) and generally form the d̗agai-d̗ar of central Makaigan with the closest historical ties to the cultural and political centers of Mák’ai in antiquity. 3 of the d̗agai-d̗ar then form autonomous regions (gará-d̗ar yakmaláwurung or GY), which are typically areas with strong cultural and/or ethnic differences from the Mák’ai heartlands. 6 of the d̗agai-d̗ar then form prefectures (kut'alá-d̗ar or KD̗), consisitingly primarily of the Kto states of eastern Makaigan. Prefectures differ from states largely as a result of historic developments in eastern Mák’ai, rather than as a result of actual political differences. The d̗agai-d̗ar of N̗t̗í-la is Mák'ai's sole existing territory (burúk-d̗ar or BD̗), and lacks a number of the privileges of states and other administrative divisions. Finally, the d̗agai-d̗a of Mk'ái is a special administrative region (d̗agai-d̗a tjurák or D̗T). Mk'ái is unique in that it is the only non-federal top level administrative region of Mák’ai, instead being controlled directly by the national government in Mk'ái-t̗ir̗.

| Map | Flag | D̗agai-d̗a | Type | Population | Capital | Image |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

File:Baaruu flag.svg | Bárú BÁR |

State (D̗D̗) |

TBD | Míl̗u |  The coast of Bárú's main island. |

|

File:Dhakan flag.svg | D̗akan D̗AK |

State (D̗D̗) |

TBD | L̗áwái-la |  A field in central D̗akan overlooking the southern end of the Makaiganic Mountain Range. |

|

File:Jaawumirr flag.svg | Jáwumir̗ JÁW |

Prefecture (KD̗) |

TBD | Lbak |  Jáwumir̗ is dominated by mountains such as these. |

|

File:K'iirama flag.svg | K'írama K'ÍR |

State (D̗D̗) |

TBD | T̗al̗ái |  Much of the south-western coast of K'írama is dominated by cliffs like these. |

|

File:Kuthuu Baarkiin flag.svg | Kut̗ú Bárkín KBÁ |

Prefecture (KD̗) |

TBD | Kut̗ú Jar̗ar |  Fields such as these are common in the fertile areas of central Kut̗ú Bárkín |

|

File:Kto Ithar flag.svg | Kut̗ú It̗ar KIT̗ |

Prefecture (KD̗) |

TBD | Tjurgúl Kat̗'ái |  The Valley of It̗ar, in southern Kut̗ú It̗ar |

|

File:Kuthuu Mbaa flag.svg | Kut̗ú Mbá KMB |

Prefecture (KD̗) |

TBD | Káwún Jár̗ |  The coast of southern Kut̗ú Mbá. |

|

File:Kuthuu Waraai flag.svg | Kut̗ú Warái KWA |

Prefecture (KD̗) |

TBD | R̗adúr Numir |  The coast of southern Kut̗ú Warái at the westernmost point of the Kto Sea. |

|

File:Laa-dhar yuk flag.svg | Lá-d̗ar Yuk LD̗Y |

State (D̗D̗) |

TBD | Patji |  Overlooking the Western Ocean from Lá-d̗ar Yuk's southernmost island. |

|

File:Laa Mruuk-kiir flag.svg | Lá Mrúk-kír LMK |

Autonomous region (GY) |

TBD | D̗úm |  Much of Lá Mrúk-kír is covered in dense forests like this one. |

|

File:Luuralai flag.svg | Lúralai LÚR |

State (D̗D̗) |

TBD | Pit̗ák |  Lúralai forms much of the agricultural heartland of Mák’ai and is dominated by fields and gentle hills. |

|

File:Lhan Yaawai flag.svg | L̗an Yáwai L̗YÁ |

State (D̗D̗) |

TBD | N̗t̗íwur |  Rock formations of the coast of L̗an Yáwai. |

|

File:Mbai flag.svg | Mbai MBA |

State (D̗D̗) |

TBD | Mbai |  The Makaiganic mountains in northern Mbai, near the border with the Ktoic Confederacy. |

|

File:Mk'aai flag.svg | Mk'ái MKÁ |

Special administrative region (D̗T) |

TBD | Mk'ái-t̗ir̗ |  The skyline of Mk'ái-t̗ir̗, Mák’ai's capital city which occupies most of Mk'ái. |

|

File:NWA flag.svg | Nggáwai w Áyi NWÁ |

State (D̗D̗) |

TBD | Úguwan̗áyi |  Nggáwai w Áyi is dominated in its central region by hard to access mountain areas, such as this one here. |

|

File:Niimirak flag.svg | Nímirak NÍM |

State (D̗D̗) |

TBD | Nggái-t̗ir̗ |  Nímirak is one of the dryest states in Mák'ai and is dominated by rocky, non-arable terrain in much of its northern and central areas. |

|

File:Njurai flag.svg | Njurai NJU |

State (D̗D̗) |

TBD | Rúwun |  View of the Ejawan Sea from the verdant hills of coastal Njurai. |

|

File:Nlaa-Nungaai flag.svg | Nlá-Nungái NNU |

State (D̗D̗) |

TBD | It̗'ak-la |  Nlá-Nungái is home to the largest old-growth forests in Mák'ai, such as this one. |

|

File:Numurraai flag.svg | Numur̗ái NUM |

Prefecture (KD̗) |

TBD | Numur Bárkín |  Much of Numur̗ái is dominated by plains and agricultural land. |

|

File:Nhthii-la flag.svg | N̗t̗í-la N̗T̗L |

Territory (BD̗) |

TBD | Lwung |  N̗t̗í-la is desolate and sparsely populated, located in the far north of Mák’ai |

|

File:Rruk'aaigan flag.svg | R̗uk'áigan R̗UK |

State (D̗D̗) |

TBD | Ár̗ak |  R̗uk'áigan is a mostly agricultural area characterised by relatively flat topography and fields. |

|

File:Rruumawaii flag.svg | R̗úmawaí R̗UM |

State (D̗D̗) |

TBD | Liwu-t̗ir̗ |  The Straight of Tigers seen on the coast of the Nayimir̗ Peninsula |

|

File:Tjuk'aai-la flag.svg | Tjuk'ái-la TJU |

State (D̗D̗) |

TBD | Diráku |  Tjuk'ái-la is a popular tourist destination as a result of its warmer weather and historical importance. |

|

File:T'ulaa flag.svg | T'ulá TUL |

Autonomous region (GY) |

TBD | Gabán̗ |  A T̗’úkai in a forest in central T'ulá. The T'ulá people have long been culturally and political distinct from the Mák’ai, with T'ulá being one of Mák’ai's three autonomous regions. |

|

File:Uuyarung flag.svg | Úyarung ÚYA |

State (D̗D̗) |

TBD | Út̗ir̗ |  Lake Mák'u in southern Úyarung, with a view of the Makaiganic Mountains in the background. |

|

File:Wuk'aai-la flag.svg | Wuk'ái-la WKL |

Autonomous region (GY) |

TBD | Wárala |  The mountains of central Wuk'ái-la, with the endemic Daughter-of-Wuk'ái flower in the foreground. |

|

File:Wuurrunga flag.svg | Wúr̗unga WÚR̗ |

State (D̗D̗) |

TBD | Wk'á |  A ruined farm house in the far north of Wúr̗unga, in a region known as The Fingers. |

|

File:Yaawurung flag.svg | Yáwurung YÁW |

State (D̗D̗) |

TBD | Málakai |  Yáwurung is home to some of the last remaining giant forests in Mák'ai and is an important area of ecological conservation. |

Foreign relations

Military

Economy

- Main article: Economy of Mák’ai.

Mák’ai is the TBD largest economy global and the largest economy in Ejawe, having a total estimated GDP (PPP) of $1,005,692,831 in 475.tk, averaging $24,128 per capita. This puts it ahead of TBD but behind TBD globally. The Mák’ai economy is relatively underdeveloped for a country of its size but is rapidly growing, being the TBD fastest growing economy globally. Mák’ai's economic stagnation is due largely to the political instability and conflicts of the last century, with the solidification of power in the hands of Mar̗uk K’úr̗ai in 436.tk heralding an era of rapid and unprecedented economic development. K’úr̗ai's free-market policy, combined with significant government investment in infrastructure projects, has seen the rapid industrial development of a number of rural Mák’ai cities, including notably Lbak and Pit̗ák. Mass urban migration has also skyrocketed since K’úr̗ai's rise to power, largely as a result of expansive infrastructure projects in cities like Mk'ái-t̗ir̗, which were almost completely rebuilt following the emergence of the new regime. Economic inequity is a major issue between rural and urban centres in Mák’ai, with the wealth gap gradually increasing as a result of government policy.

The Mák’ai economy largely consists of primary and some secondary industries, with the largest economic sectors consisting of agriculture, mining, and manufacturing respectively. As a result of the country's size, Mák’ai has access to a number of important natural resources, particularly iron and precious metals in the Makaiganic Mountain Range. Much of the land in western and southern Makaigan is also highly fertile, and such is home to the country's major agricultural industries. Mák’ai is a global exporter of wheat and other cereal goods, many of which are grown in southern Makaigan. As a result of the concentration of both of these industries in southern and western Makaigan, it is this part of Mák’ai which forms the country's industrial heartlands.

Outside of Makaigan, lumber and agriculture form minor industries in the west of the country, particularly in the highly wooded states of Nlá-Nungái and T'ulá. Tourism is a major industry in the southern Mák’ai islands, whose more tepid climate and historical interest make them popular tourist destinations, particularly from other Ejawan states. Energy is another medium-sized industry in Mák’ai and consists primarily in the extraction of oil and coal from the northern seas and Makaiganic mountains respectively. Gradually, tertiary industries are becoming more prominent in the Mák’ai economy as the country becomes more politically stable, and is centred around financial and academic services in the countries largest cities. In particular, cities such as Mk'ái-t̗ir̗ and Kut̗ú Jar̗ar are becoming popular destinations for international students as a result of the growing global recognition of their universities. It is widely believed that, as the Mák’ai economy continues to develop, these tertiary industries will play an increasingly important role not only in attracting capital, but also in rebuilding international relations between Mák’ai and foreign powers.

The currency of Mák’ai is the Mák’ai T'ula (MKT), whose symbol is ₮. The monetary policy of the Mák’ai Commonwealth is controlled by the Reserve Bank of Mák’ai, which is headquartered in the nation's capital of Mk'ái-t̗ir̗. The exchange rate of Mák’ai T'ula with other global currencies has stabilised in recent years following the market crash and mass inflation of the late 440.tks, but remains a relatively low valued currency in comparison to others globally, such as the Kaishuri Fïdir.

Agriculture, mining, and manufacturing

The Mák’ai economy is primarily based in primary and secondary industries, of which mining, agriculture, and light manufacturing are the largest sectors. Mining for metals is the most expansive and lucrative sector of the Mák’ai economy, with an estimated 40% of the country's GDP coming from metal extraction, and three of the top five largest and wealthiest Mák’ai companies being based in mining. In particular, iron, nickel, copper, and titanium are the most widely exported metals respectively, all of which are found in the Makaiganic Mountain Range. As a result, much of Mák’ai's heavy mining industry is based in western Makaigan, particularly the states of R̗uk'áigan and Úyarung. Úyarung in particular is home to approximately 60% of all mining industry in Mák’ai and as such is one of the country's wealthiest states. Mining for precious metals, such as gold and silver, as well as gems such as Tiyanak and Firestone, also exist to a smaller scale in Nungái-la. In Mák’ai culture, mining is particularly associated with the Ngáarduk gender and the spiritual cult of D̗awun. As such, the act and industry of mining have an important cultural role for Mák’ai people, as does the secondary industry of metalwork.

Light manufacturing and related industries also form a major part of the Mák’ai economy, accounting for approximately 28% of the country's total GDP. Historically, Mák’ai culture was renown for its skill with metalwork and engineering, with this tradition continuing today in the largescale production of high quality metal products. Mák’ai is also a significant global producer of cars, with several major international automobile companies hosting their factories in Mák’ai. Many of these, including the much beloved Mák’ai car companies of Malína and BLN, are based in the northern Ktoic city of Káwún Jár̗, considered to be one of the major industrial centres of Mák’ai. In recent years, Mák’ai has also seen an explosion in the manufacturing of electronics, in particular computer components. Much of this development has been due to the offshoring of production by international companies to Mák’ai, which has in turn helped to rebuild the Mák’ai economy following the devastating Civil War of 445.tk.

Agriculture is another major sector of the Mák’ai economy, accounting for approximately 17% of the country's overall GDP. Historically, the fertile growing regions of southern Makaigan and Wúk'ai-la have been home to the majority of the country's agricultural production. Mák’ai is a global exporter of agricultural goods, in particular wheat and barley, the majority of which is grown in these regions. Rice is also grown to a moderately large extent in some of the warmer parts of the country. Smaller agricultural products, in particular fruits and wines, are also produced in these regions, with Wúk'ai-la in particular being home to a thriving fruit industry. Mák’ai is also the largest global producer of Nggan̗í, a popular stone fruit endemic to Ejawe, which it exports internationally. Other notable agricultural products include apricots, almonds, oranges, and apples.

Tourism

- Main article: Tourism in Mák’ai. See also: Lonely Planet: Mák’ai.

Tourism in Mák’ai has steadily increased since the country's return to political stability after the end of the Mák’ai Civil War in 436.tk, with the total number of foreign tourists increasing from 7.4 million in 448.tk to 13.9 million in 468.tk. Mák’ai is the second most visited country in Ejawe (after Mtasai), but remains a relatively obscure travel destination for many international tourists. Cheap travel costs, combined with renewed government efforts to increase tourism to the country and the large number of diverse cultural, historical, and ecological tourist attractions in Mák’ai, have meant that travel to the country is becoming increasingly attractive and popular, especially among tourists from western Aicho. Of the tourists that visit Mák’ai, the vast majority come from other Ejawan states, including the Ktoic Confederacy, Mtasai, Imai, and Nga. Outside of Ejawe, the largest number of international tourists come from Kaishuri and Imisquun respectively.

Cultural interest is the most commonly cited reason for travelling to Mák’ai, which includes one of the world's highest number of historic sites. Most notably, the ancient cities of the Kto Vbarkîn in eastern Makaigan attract millions of visitors each year, as does the nation's capital of Mk'ái-t̗ir̗. Other important historic sites include the ancient cities of the regions of Tjuk'ái-la, T'ulá, and Wuk'ái-la. Many of the more traditional areas of Mák’ai are also increasingly attracting tourism as a result of their unique culture and history, especially in the northern islands of Lá Mrúk-kír. Other common reasons for tourism to Mák’ai include ecological tourism, especially to the dramatic Makaiganic mountains, giant forests of Yáwurung, the desolate islands of N̗t̗í-la in the north, and the spectacular mountains and rainforests of the Valley of It̗ar and Áyi. The Makaiganic mountains are also home to major international snowsporting events, including the annual Tárganákí Wintersports held in central Úyarung. Mák’ai's southern islands also have excellent surfing conditions, and are the centres of several prominent international surfing competitions.

Tourism in Mák’ai is also increasing due to the increased number of international students and business people arriving in the country, particularly as a result of increased government travel and business incentives. Tourism from international students alone is expected to account for some 10% of tourism in Mák’ai, especially around the popular university cities of eastern Makaigan. Collectively, these demonstrate that growing international exposure to Mák’ai culture and history in the wake of decades of isolation and conflict has meant that tourism and travel for other purposes has steadily increased in Mák’ai, as has been the hope of the Mák’ai government. Mák’ai citizens that live abroad, having fled the country during the troubles of the Koi az Ktarh, also contribute substantially to the number of tourists that visit Mák’ai each year.

A castle in the old town of Mk'ái-t̗ir̗.

The skyline of Mk'ái-t̗ir̗.

A war memorial in central Nungái-la.

A detail of the National Government in Mk'ái-t̗ir̗.

A modern-day monument to D̗awun.

Part of the ancient city of Tjurgúl Kat̗'ái in south-eastern Makaigan.

The skyline of the old town of Kut̗ú Jar̗ar, the ancient capital of the Kto Vbarkîn.

A typical village in Nungái-la.

An ancient monastery in the Makaiganic mountain range.

A seaside town in Tjuk'ái-la, a popular tourist destination in the south of Mák’ai.

The Valley of It̗ar in south-eastern Makaigan.

The islands of N̗t̗í-la in Mák’ai's far north are a growing ecotourism location.

The famous giant forests of Yáwurung.

A Ngárduk T'ulá person. T'ulá is a popular destination for cultural tourism in Mák'ai.

A T̗'úkai person from Lá Mrúk-kír wearing a ceremonial wax-mask. Lá Mrúk-kír is another popular destination for cultural tourism in Mák'ai.

A ski resort in central Makaigan.

Energy

- Main article: Energy in Mák’ai.

The bulk of Mák’ai energy is renewable, in particular coming from wind, water, and nuclear sources. Mák’ai's significant technological advancements in the Koi az Pser̄arh were made primarily off the back off non-renewable energy sources, in particular coal found in the Makaiganic mountain ranges, and later oil extracted from the seas north of Makaigan. While a large proportion of the Mák’ai economy is still based in the extraction and exportation of these energy sources, investment in renewable energy sources during the late 4th century has meant that the Mák’ai economy is no longer dependent on non-renewable energy sources.

Many of the largest energy providers in Mák’ai are nationalised. Most notably, the Nungái Hydroelectric Power Company (NHPC), which is the largest energy provider in Mák’ai, is state-owned, as are the Bakán̗-Maláwí Ltd. and Makaiganic Aeroenergetics companies, which are the second and third largest energy providers in the country respectively. As a result, almost 85% of energy is produced domestically by state-owned companies in Mák’ai, providing relatively cheap electricity to most of the country. This was largely a result of the widespread electrification programs and energy reforms of Makáng Gíwá between 375.tk to 389.tk, and has led to the energy sector being one of the most stable in the Mák’ai economy. The remaining 15% of energy production in Mák’ai comes from private businesses, most of which operate in the extraction of non-renewables and whose primary business comes from exportation.

Transport

- Main article: Transport in Mák’ai. See also: Train system of Mák’ai, Tai Mák’ai, and List of highways in Mák’ai.

Science and technology

Communications

- Main article: Telecommunications in Mák’ai. See also: TBD.

Since the 430.tks Mák’ai has developed an effective and extensive telecommunications network, connecting its population through post, internet, and telephone services. At the end of the Mák’ai Civil War in 436.tk, all telecommunication companies in Mák’ai were centralised under direct control of the State Institute for Media and Communications (Mák’ai: TBD), which oversaw the reorganisation of previous telecommunication systems in the country under the auspices of Takán's new government.

Demographics

Ethnic groups

Major cities

- Main article: List of settlements in Mák’ai.

While Mák’ai has a number of long-standing urban centres, notably in the Mák’ai heartlands around the national capital and in the Ktoic prefectures, much of the country remained relatively undeveloped until the late Tjik'ulak. As a result, there is a significant contrast between areas of high urbanisation and wealth and less developed rural areas - a problem which has only been exacerbated since the Mák’ai Civil War. As a result, there has been a steady influx of population into urban centres and an increase in rural town abandonment, especially in the north of Makaigan. Humanitarian and economic crises following the end of the Civil War also saw a large movement of the Mák’ai population into major urban centres, with the consequence that Mák’ai's largest cities experienced a rapid and unprecedented population growth in recent years. This has resulted in the emergence of Mk'ái-t̗ir̗ as the only megacity in Ejawe, and the expansion of the Jar̗ar-Numir-N̗gali Conurbation in eastern Makaigan. Cities in Makaigan tend to be far larger than those in other insular territories of Mák’ai, with the sole exception of Wárala in Wuk'ái-la, which is the only non-Makaiganic city to feature in the top 10 largest cities in the country.

Largest cities or towns in Mák’ai

474.tk Census | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Name | D̗agai-d̗a | Pop. | Rank | Name | D̗agai-d̗a | Pop. | ||

Mk'ái-t̗ir̗  Kut̗ú Jar̗ar |

1 | Mk'ái-t̗ir̗ | Mk'ái-t̗ir̗ | 11,827,915 | 11 | N̗gali | Úyarung | 996,314 |  R̗adúr Numir  Út̗ir̗ |

| 2 | Kut̗ú Jar̗ar | Kut̗ú Bárkín | 5,623,097 | 12 | Kut̗ú Ják | Kut̗ú Bárkín | 954,309 | ||

| 3 | R̗adúr Numir | Kut̗ú Warái | 4,876,219 | 13 | Tjurgúl Kat̗'ái | Kut̗ú It̗ar | 924,086 | ||

| 4 | Út̗ir̗ | Úyarung | 4,312,996 | 14 | Diráku | Tjuk'ái-la | 918,612 | ||

| 5 | Numur Bárkín | Numur̗ái | 3,012,644 | 15 | Málakai | Yáwurung | 903,812 | ||

| 6 | Gabán̗ | T'ulá | 2,976,812 | 16 | Lbak | Jáwumir̗ | 895,418 | ||

| 7 | L̗áwái-la | D̗akan | 2,558,716 | 17 | Patji | Lá-d̗ar Yuk | 859,553 | ||

| 8 | Káwún Jár̗ | Kut̗ú Mbá | 1,712,091 | 18 | N̗t̗íwur | L̗an Yáwai | 827,641 | ||

| 9 | Wárala | Wuk'ái-la | 1,644,090 | 19 | Úguwan̗áyi | Nggáwai w Áyi | 773,912 | ||

| 10 | Nggái-t̗ir̗ | Nímirak | 1,116,091 | 20 | Liwu-t̗ir̗ | R̗úmawaí | 708,602 | ||

Languages

- Main articles: Mák’ai language, Pan-Ejawan languages, and Languages of Mák’ai.

While at least 50 indigenous Pan-Ejawan languages are spoken within the territory of Mák’ai, the national language policy established by Rawak Takán in 448.tk following the end of the Mák’ai Civil War gives Mák’ai-wa as the sole official national language. Since the beginning of the Tjik'ulak and the expansion of powers of the Second and Third Mák’ai Empires, linguistic diversity in Mák’ai has been threatened by nationalising policies aimed to increase a sense of national unity. As a result, Mák’ai today faces some of the highest rates of language endangerment of any Pan-Ejawan-speaking country in Ejawe.

Autonomous regions (Mák’ai: gará-d̗ar yakmaláwurung, or GYs) are unique as administrative divisions of Mák’ai in that they are able to determine their own regional language policy as a concession to the increased autonomy of these formerly non-Mák’ai states. As a result, the three Autonomous Regions of Lá Mrúk-kír, T'ulá, and Wuk'ái-la each maintain official languages besides Mák’ai in regional government and education. In both Lá Mrúk-kír and Wuk'ái-la a single regional language is dominant - Wrutha and Wukkai respectively - each of which is spoken by a significant portion of the local population either as a native language or second language after Mák’ai-wa. The isolation of these two insular states from mainland Makaigan has had a positive effect on their continued use as a source of regional pride. In Tul'á the situation is less stable, both as a result of the large number of Northern Mtasaic languages spoken in the area and the influence of Mák’ai-wa from the southern Mák’ai heartlands. Of the various languages spoken by Tul'á peoples, the most widely spoken are Mijai and Mtakai. Mijai was historically much more widely spoken as a lingua franca, but has loss this status as a result of the spread of Mák’ai-wa.

Outside of these autonomous regions, the six Mák’ai Prefectures (kut'alá-d̗ar) also maintain Kto as a co-official language. The high density of ethnic Kto people in the region and historic status of Kto as a prestigious linguistic variety have led to the maintenance of the language in the area. A number of other Ktoic languages are spoken in the Kto prefectures of eastern Makaigan, but all are endangered. The most widely spoken Ktoic languages after Kto are Takanese andIshari in Kut̗ú It̗ar, and Ktai in Kut̗ú Mbá. In the far north of Mák’ai, near the border with the Ktoic Confederacy, a number of Northern Ktoic languages are spoken, including, most prominently, Hzhari, which forms the largest Northern Ktoic ethno-linguistic group in Mák’ai. All Ktoic languages in eastern Makaigan have had a significant impact on the local varieties of Mák’ai-wa as well, evident in the region's distinct accent and vocabulary, much of which is loaned from Ktoic languages.

Outside of these relatively stable languages, Mák’ai is also home to all languages in the Makaiganic subbranch of the Pan-Ejawan language family (with the exception of some Northern Makaiganic languages spoken in the Ktoic Confederacy). Many of these are at risk, although insular and montane languages tend to fare better than those of the southern Makaiganic lowlands. The Central Makaiganic languages in particular have been decimated by national language policy in Mák’ai over recent centuries, with now only a few remaining with more than 1000 speakers. Revitalisation and documentation efforts are underway for many of these languages, but remain for the most part underfunded by the government.

While multilingualism in Pan-Ejawan languages is common across Mák’ai beyond the Mák’ai heartlands, knowledge of foreign languages remains largely limited. Data released in 462.tk by the National Bureau of Statistics reported that the most widely reported foreign languages learned at school in Mák’ai were Mtasa, Azari, Kai, and Imisquun. Among the population of foreigners living in Mák’ai, Mtasa, Haʞhai, Ng!oő, and Kai were reported as the most widely spoken languages other than Mák’ai-wa at home.

The following table gives translations of the English phrase 'Hello! My name is Liwu and I am from Mák’ai' in six of the most widely spoken languages in Mák’ai:

| Language | Language Family | Written | Recording |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mák’ai (Mk'ái-t̗ir̗) | Southern Makaiganic | Ít̗ák! Míka Liwu-pak w mun Mák’ai-pal̗a. | |

| Kto (Kut̗ú Jar̗ar) | Southern Ktoic | Vzêrêi! Dzô kta r̄a gîn az Livu i dzô Makai tsarh. | |

| Wrutha (D̗úm) | Northern Mtasaic | Hth'amor! Ywri Liw, Mk'ai-m | |

| Wukkai (Wárala) | Ngaic | nGan Paki! Wiyosh-nGi Liwu ba, gao Makkai-mo | |

| Mijai (Gabán̗) | Northern Mtasaic | Neyjja! Qast Liwu ne Makkai-mi | |

| Northern Tjuwa (Tjutjáwá) | Northern Makaiganic | Qmaáqsaq! Moú Líwú waq óo máak'aí c'uú |

Religion

Health

Education

Culture

Art

Music

Literature

Architecture

Cinema

Media

Cuisine

Sports

Holidays and festivals

Notes

- ↑ The ancient Numurian language whence the name Hrush is believed to have been derived is a now-extinct Ktoic language related to modern-day Kto. Numurian has been reconstructed based on samples of writing that have been found from Ancient Numur, which are oftentimes the only instances of names of Numurian people or places. For this reason, the names of Numurian places or people are given here in their Numurian romanisations, however the Mák’ai versions of these names are often used in Mák’ai academic literature.

- ↑ Likely the River It̗ar.

- ↑ In this instance, this likely refers to the sacrifical practice of strangling men and boys as an offering to Thurn, and throwing women and girls off a tall building or peak as an offering to Thain. Sacrifices to Thurn, as the God of the Earth, often involved strangulation or burrial alive, while sacrifices to Thain, as Goddess of the Sky typically involved being thrown from high places.

- ↑ Note that 'commonwealth' here is used as a literal translation of the Mák’ai word nbátalak, which literally translates to 'common good' or 'common wealth'. Conceptually, nbátalak may be more similar to a political party in English, and for this reason the NMN̗ is sometimes translated as the 'Party of All Mák’ai'.

- ↑ 'Union' here is a direct translation of the Mák’ai term jugán-ngu, and does not refer to a labour union.