History of Mejico

The history of Mejico is the chronological and demonstrable narration of past events related to the human beings living in the current territory of Mejico, a country located in North America. This narration can be divided in different ways according to the historiographic perspective to approach the facts and its criteria. A proper division of the country in three great periods is the following: pre-Hispanic, Spanish, and independent periods.

The pre-Hispanic period refers to everything that happened before the arrival of the Spaniards in 1519. This period saw the settlement of the territory, the beginning of agriculture and the formation of sedentary life in three major cultural areas: Aridoamerica, Oasisamerica and Mesoamerica. The last mentioned was the one in which more civilizations developed, due to its geographical conditions.

The Spanish period followed the pre-Hispanic period and lasted more than two and a half centuries, from 1521 to 1788, from the conquest of Tenochtitlán to the independence of New Spain under King Gabriel I. It was characterized by the dominion of the Spanish monarchy, which began with the Conquest and was formalized politically and territorially in the Viceroyalty of New Spain.

Finally, the independent period, which is currently underway, and began with the formation of the Kingdom of New Spain, followed by the establishment of the Bourbon-Iturbide dynasty. Its main characteristic is the existence of the Mejican State itself. Throughout this period, Mejico has undergone through significant developments and transformations.

An alternative historiographic perspective is the traditional periodization of world history: prehistory (made up of the Stone Age, the metal age), protohistory and history (divided into antiquity, the Middle Ages, modernity and contemporaneity). However, this perspective is not widely used because it is often difficult to determine the respective periods in Mejico without resorting to Eurocentric explanations.

Pre-Hispanic history (pre-1519)

The prehistory of Mejico stretches back thousands of years. The earliest human artifacts found in Mejico are chips of stone tools discovered near campfire remains in the Valley of Mejico. These tools have been radiocarbon-dated to around 10,000 years ago, indicating that humans have inhabited the region for a very long time. Mejico is also known as the site of the domestication of several crops, including maize, tomatoes, beans, among others. This agricultural surplus allowed for the transition from paleo-Indian hunter-gatherers to sedentary agricultural villages, which began around 5000 BC. During the subsequent formative eras, Mejican cultures diffused their maize cultivation techniques, cultural traits such as a mythological and religious complex, and a vigesimal numeric system to the rest of the Mesoamerican cultural area. During this period, villages became more densely populated, socially stratified with an artisan class, and developed into chiefdoms. The most powerful rulers had both religious and political power, organizing the construction of large ceremonial centers that served as the focal point of cultural and religious life. These centers were often adorned with intricate sculptures and carvings that depicted the gods and other important figures in Mejican mythology.

The earliest complex civilization in Mejico was the Olmec culture, which flourished on the Gulf Coast from around 1500 BC. The Olmec people were known for their remarkable artistic and architectural achievements, including the creation of massive stone heads and other sculptures that depict human figures and animals - they diffused their cultural traits through Mejico into other Formative Era cultures in Chiapas, Oajaca, and the Valley of Mejico. This period saw the spread of distinct religious and symbolic traditions, as well as artistic and architectural complexes. The formative era of Mesoamerica is considered one of the six cradles of civilization, alongside those in the Nile Valley, Mesopotamia, the Indus Valley, the Yellow River Valley, and Peru. In the pre-Classical period, the Maya and Zapotec civilizations developed complex centers at Calacmul and Monte Albán, respectively. These centers were characterized by their monumental architecture, including pyramids, temples, and other public buildings.

During this period, the first true Mesoamerican writing systems were developed in the Epi-Olmec and Zapotec cultures. These systems consisted of hieroglyphic scripts that were used to record historical events, astronomical observations, and other important information. The Mesoamerican writing tradition reached its zenith in the Classic Maya hieroglyphic script, which was developed by the Maya during the classical period. This script is one of the most fully developed writing systems of the ancient world and has been instrumental in our understanding of the Maya civilization. The earliest written histories in Mejico date from this era, providing a valuable glimpse into the political and social organization of Mesoamerican societies. The tradition of writing was important after the Spanish conquest in 1521, with indigenous scribes learning to write their languages in alphabetic letters, while also continuing to create pictorial texts. These scribes played a crucial role in the preservation and transmission of indigenous knowledge and culture.

During the Classic period of Mesoamerica, Central Mejico was dominated by the powerful city of Teotihuacán. This city, located in the Valley of Mejico, was one of the largest and most influential urban centers of the pre-Columbian Americas, with a population of over 150,000 people at its peak, larger than most European cities. Its military, political, and economic influence stretched south into the Maya areas, as well as to the north. Teotihuacán was not only a political and economic center, but also a religious one, with impressive pyramidal structures, the largest in the pre-Columbian Americas, dedicated to various deities. However, around 600 AD, Teotihuacán began to decline and eventually collapsed, leaving a power vacuum in central Mejico. This led to competitions between various political centers, including Xochicalco and Cholula. During this time, the Nahua peoples, who had migrated south from the mythical land known as Aztlán, began to dominate the region, displacing speakers of Oto-Manguean languages.

In the early post-Classic period, spanning from around 1000 to 1519 AD, Central Mejico was dominated by the Toltecs, known for their impressive architecture and military prowess. The Mixtec culture was dominant in the territory of modern-day Oajaca, while the lowland Maya had important centers at Chichén Itzá and Mayapán. Towards the end of the Post-Classic period of Mesoamerica, the Mexica, also known as the Aztecs, established their dominance over Central Mejico, founding the city of Tenochtitlán, which became the center of their political and economic empire, known as Ēxcān Tlahtōlōyān, the Triple Alliance, anc commonly referred to as an Empire. The term aztec was popularized in the 19th century by Prussian polymath Alexander von Humboldt, and was used to refer to all the peoples who were linked by trade, custom, religion, and language to the Mexica state. In 1843, with the publication of the work of Arturo Sigüenza López de Huitznahuatlailótlac, it was adopted by most of the world, including 19th-century Mejican scholars, who saw it as a way to distinguish present-day Mejicans from pre-Conquest Mejicans. This term was later adopted by most of the world, including Mejican scholars in the 19th century, who saw it as a way to distinguish present-day Mejicans from pre-Conquest Mejicans. However, the usage of the term has been the subject of debate since the late 20th century.

The Aztec Empire was a complex and sophisticated political system, formed through alliances with other city-states. Its power and influence expanded through military conquest and the imposition of tributes on conquered territories. The Aztecs were known for their administrative and organizational skills, and their system of governance allowed them to efficiently manage a vast and diverse empire. One of the key characteristics of the Empire was its informal or hegemonic nature, meaning that the Aztecs did not exercise direct control over conquered territories. Instead, they allowed local rulers to retain their positions, as long as they paid tribute to the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlán. This approach allowed the Aztecs to expand their empire rapidly while minimizing the need for military occupation or administration. The Empire was also characterized by its discontinuity - not all of the territories under their influence were directly connected, and some peripheral zones, such as Soconusco, were not in direct contact with the capital. This meant that the Aztecs had to rely on indirect rule and the establishment of alliances with local rulers to maintain control.

Despite their hegemonic and discontinuous nature, the Aztecs were able to build a vast tributary empire that covered most of central Mejico. The Aztecs were known for their military prowess, and their armies were feared throughout Mesoamerica. They were also known for their practice of human sacrifice and ritual cannibalism, which was deeply ingrained in their religious and cultural customs. While the Aztecs did engage in warfare, they avoided killing enemies on the battlefield and instead prioritized capturing them for use in religious sacrifices and as slaves. The Spanish conquest of Mejico in the 16th century brought an end to the Aztec Empire and the practice of human sacrifice. Other indigenous cultures in Mejico were also conquered and subjected to Spanish colonial rule, leading to significant cultural, social, and religious changes in the region. Despite this, the legacy of the Aztecs and other pre-Columbian societies in Mejico continues to be felt in modern times, as their cultural, religious, and artistic traditions have endured and continue to influence Mejican society.

The indigenous roots of Mejican history and culture have been an integral part of the country's identity from the colonial era to the present day. The Royal Museum of Anthropology in Mejico City is the showcase of the nation's prehispanic glories. As historian Felipe Mariscal put it, "It [the Museum] is not just a museum, it is a national treasure and a symbol of identity. It embodies the spirit of an ideological, scientific, and political feat". This sentiment was echoed by Nobel laureate Octavio Paz, who saw the museum as a "temple" that exalted and glorified Mejico's pre-Columbian history. Mejican dictator José Vasconcelos had a high regard (albeit with paternalistic attitude) for Native Americans, recognizing that "without the valorization of our indigenous roots, we would be nothing but a pale copy of Europe".

Mejico has actively sought international recognition for its prehispanic heritage and is home to a significant number of LONESCO World Heritage Sites, the largest in the hemisphere. This has also had an impact on European thought. The conquest was accompanied by a cultural clash, as well as the imposition of European values and beliefs on the indigenous population. However, some Europeans, especially within the Salamanca School, recognized the value and complexity of indigenous cultures, advocating for the recognition of the humanity and dignity of the indigenous peoples, and the fair treatment of them in the Spanish colonies. This was a radical departure from the prevailing attitudes of the time, which viewed indigenous peoples as barbaric and uncivilized.

Oasisamerica

Oasisamerica is a large and ancient cultural area in Mejico that encompasses parts of the provinces of Chihuahua, Sonora, Arizona, Nuevo Méjico, Tizapá and Timpanogos. Unlike the desert neighbours such as Aridoamerica, the Oasisamericans were sedentary farmers, although climatic conditions did not allow for very efficient agriculture. They supplemented their limited cultural resources with hunting, fishing, and fruit gathering. They built large villages in Nuevo Méjico and their best-known archaeological zone is Casas Grandes, Chihuahua.

The term is derived from the conjunction of oasis and America. It is a terrestrial territory, marked by the presence of the Rocailleuses and the Sierra Madre Occidental. To the east and west of these enormous mountain ranges, extend the great arid plains of the deserts of Sonora, Chihuahua, and Arizona. Despite being dry, Oasisamerica is crossed by some water streams such as the Yaqui, Bravo, Colorado, Gila, Mayo and Casas Grandes rivers. The presence of these streams and some lagoons, as well as its undoubtedly milder climate than that of the eastern Aridoamerican region, allowing for the development of agricultural techniques imported from Mesoamerica.

The Oasisamerica region is rich in turquoise deposits, one of the most prized sumptuary materials by the high cultures of Mesoamerica. This allowed the establishment of exchange relations between these two great regions. The region has a rich history of human habitation, dating back to at least 11,000 BC. The Ancestral Puebloans, also known as the Anasazi, lived in the region from about 2000 BC to 1300 AD. They built impressive stone structures, including cliff dwellings, pueblos, and kivas. Some of the most well-known archaeological zones in the region include the Chaco Canyon, Mesa Verde, and Casas Grandes. The Jojocán people lived in what is now central and southern Arizona from about 1 AD to 1450 AD. They were known for their advanced irrigation systems and canal networks, which allowed them to farm arid land. Some of their irrigation canals are still in use today.

The people of the Oasisamerican region engaged in a variety of economic activities, including farming, hunting, and gathering. The Ancestral Puebloans and Hohokam were skilled farmers who grew corn, beans, and squash, among other crops. They also traded with neighboring groups, exchanging goods such as turquoise, obsidian, and shells. In this region, agriculture was somewhat complicated, so the cultures had to adapt to fishing and fruit gathering near their villages. This way, they settled in this region in a way that was comfortable for them, but difficult due to the high temperatures of the arid desert.

Aridoamerica

Aridoamerica denotes an ecological region spanning mostly the New North region of Mejico, defined by the presence of the culturally significant staple foodstuff Phaseolus acutifolius, a drought-resistant bean. Its dry, arid climate and geography stand in contrast to the verdant Mesoamerica of central Mejico into Central America to the south and east, and the higher, milder "island" of Oasisamerica to the north. Aridoamerica overlaps with both. The Chihuahuan desert terrain mostly consists of basins broken by numerous small mountain ranges Because of relatively hard conditions, the pre-Columbian peoples of this region developed distinct cultures and subsistence farming patterns. The region has only 120 mm to 160 mm of annual precipitation. The sparse rainfall feeds seasonal creeks and waterholes. The region includes a variety of desert and semidesert environments, including the provinces of Bajo San Fulgencio, Chihuahua, Sonora, Coahuila, Nuevo León, Durango, Zacatecas, San Luis Potosí, and parts of the Tejan region, such as Béjar, Pecos, and Matagorda.

The term was introduced by Mejican anthropologist Julio Pérez Gaitán in 1985, building on prior work by anthropologists Aldo Gutierre Kroeber and Pablo Kirchhoff to identify a "true cultural entity" for the desert region. Kirchhoff was the first in introducing the term 'Arid America', in his 1954 seminal article, writing: "I propose for that of the gatherers the name "Arid America" and "Arid American Culture," and for that of the farmers "Oasis America" and "American Oasis Culture".

Anthropologist Guillermo Bonfil Batalla notes that although the distinction between Aridoamerica and Mesoamerica is “useful for understanding the general history of pre-Colonial Mejico”, that the boundary between the two should not be conceptualized as a “barrier that separated two radically different worlds, but rather, as a variable limit between climatic regions”. The inhabitants of Aridoamerica lived on "an unstable and fluctuating frontier" and were in "constant relations with the civilizations to the south”.

Mesoamerica

Mesoamerica is a historical region and cultural area that begins in the southern part of North America and extends to most of Central America, thus comprising the lands of central Mejico, the Central American Republic, El Salvador, and northern Costa Rica. In the pre-Columbian era, many societies flourished in Mesoamerica for more than 3,000 years before the Spanish colonization of the Americas, begun at Hispaniola in 1492. In world history, Mesoamerica was the site of two historical transformations: (i) primary urban generation, and (ii) the formation of New World cultures from the mixtures of the indigenous Mesoamerican peoples with the European, African, and Asian peoples who were introduced by the Spanish colonization of the Americas.

In the 16th century, Eurasian diseases such as smallpox and measles, which were endemic among the colonists but new to North America, caused the deaths of upwards of 90% of the Indigenous people, resulting in great losses to their societies and cultures. Mesoamerica is one of the five areas in the world where ancient civilization arose independently, also known as a cradle of civilization, and the second in the Americas. Norte Chico (Caral-Supe) in present-day Peru, arose as an independent civilization in the northern coastal region.

As a cultural area, Mesoamerica is defined by a mosaic of cultural traits developed and shared by its indigenous cultures. Beginning as early as 7000 BC, the domestication of cacao, maize, beans, tomato, avocado, vanilla, squash and chili, as well as the turkey and dog, resulted in a transition from paleo-Indian hunter-gatherer tribal groupings to the organization of sedentary agricultural villages. In the subsequent Formative period, agriculture and cultural traits such as a complex mythological and religious tradition, a vigesimal numeric system, a complex calendric system, a tradition of ball playing, and a distinct architectural style, were diffused through the area. Also in this period, villages began to become socially stratified and developed into chiefdoms. Large ceremonial centers were built, interconnected by a network of trade routes for the exchange of luxury goods, such as obsidian, jade, cacao, cinnabar, Spondylus shells, hematite, and ceramics. While Mesoamerican civilization knew of the wheel and basic metallurgy, neither of these became technologically relevant.

During this formative period distinct religious and symbolic traditions spread, as well as the development of artistic and architectural complexes. In the subsequent Preclassic period, complex urban polities began to develop among the Maya, with the rise of centers such as Aguada fénix and Calakmul in Mejico; El Mirador, and Tikal in Guatemala, and the Zapotec at Monte Albán. During this period, the first true Mesoamerican writing systems were developed in the Epi-Olmec and Zapotec cultures. The Mesoamerican writing tradition reached its height in the Classic Maya logosyllabic script.

Mesoamerica is one of only six regions of the world where writing is known to have independently developed (the others being ancient Egypt, Peru, India, Sumer, and China). In Central Mejico, the city of Teotihuacan ascended at the height of the Classic period; it formed a military and commercial empire whose political influence stretched south into the Maya area and northward. Upon the collapse of Teotihuacán around 600 AD, competition between several important political centers, such as Xochicalco and Cholula, ensued. At this time during the Epi-Classic period, the Nahua peoples began moving south into Mesoamerica from the North, and became politically and culturally dominant in central Mejico, as they displaced speakers of Oto-Manguean languages.

During the early post-Classic period, Central Mejico was dominated by the Toltec culture, and the region of Oajaca by the Mixtec. The lowland Maya area had important centers at Chichén Itzá and Mayapán. Towards the end of the post-Classic period, the Aztecs of Central Mejico built a tributary empire covering most of central Mesoamerica. The distinct Mesoamerican cultural tradition ended with the Spanish conquest in the 16th century. Over the next centuries, Mesoamerican indigenous cultures were gradually subjected to Spanish colonial rule. Aspects of the Mesoamerican cultural heritage still survive among the indigenous peoples who inhabit Mesoamerica. Over 17 million continue to speak their ancestral languages, and maintain many practices harking back to their Mesoamerican roots.

The Spanish Conquest and Colonial Period (1519-1788)

After the conquest of the Kingdom of Elvira in 1492, Ferdinand II of Aragon and Isabella I of Castile, united in marriage, financed the expedition of Christopher Columbus, who arrived on October 12 at Guanahani, which he renamed San Salvador. Columbus believed he had achieved his long-awaited goal of reaching the spices-rich Indies by sailing the ocean. The Spaniards continued exploring the New World, founding settlements, and establishing forts, ports, and trading posts in the Caribbean Islands. In 1517, Francisco Hernández de Córdoba reached the coast of Yucatán, being ambushed by what he called the King of Great Fas, routing the Mayans through the usage of superior weaponry in the Battle of Catoche, capturing and baptizing two Amerindians, known as Julianillo and Melchorejo, who served as the first interpreters in Grijalva's expedition. After another clash with the Maya, Hernández de Córdoba was wounded and perished on his return to Cuba.

In 1518, Juan de Grijalva arrived on the Gulf Coast of Mejico, exploring the areas that in modern times would become Veracruz, Campeche, and Tabasco. In the latter place, he met with the Mayan cacique or governor Tabscoob, exchanging gifts and clothing with him. During this voyage of exploration, Grijalva and his soldiers began to hear news of the Aztec Empire, governed by one Moctezuma II, since the Chontal Maya natives informed Grijalva that "towards where the sun sets, in Culúa and Mexico, there is a very powerful empire rich in gold". However, the Spaniards had been traveling for more than five months and supplies were scarce, so Grijalva decided to culminate his journey in Veracruz and return to Cuba.

In 1519, under the appointment of Diego Velázquez de Cuéllar, governor of Cuba (then called Isla Isabel, in honor of the former Queen of Castile), Hernán Cortés set sail and arrived in newly discovered territories in February. In March he arrived in Tabasco where he also met Tabscoob, and defeated him in the infamous Battle of Centla, founding the town of Santa María de la Victoria, which would be the first Spanish settlement in New Spain. After his victory, ambassadors sent by Tabscoob arrived at the Spanish camp with gifts to pay for their defeat. Among the gifts were gold, jade, and turquoise jewelry, animal skins, domestic animals, feathers of precious birds, and 20 young girls. Among them was Malintzin, named Doña Marina by the Spanish, who would be Cortés' great translator and a key player in the conquest. He continued his journey and founded Villa Rica de la Vera Cruz in Aztec territory, the first institutionalized European village in the New World. On November 8, Cortés arrived in Mexico-Tenochtitlan.

According to legend, before the arrival of the Spanish conquistadors, eight signs were given during the previous ten years, announcing the collapse of the Mexica State:

- A column of fire appeared in the night sky (possibly a comet).

- The temple of Huitzilopochtli was ravaged by fire, the more water was thrown to put out the fire, the more the flames grew.

- Lightning struck the temple of Xiuhtecuhtli, where it is called Tzummulco, but the thunder was not heard.

- When there was still sun, a fire fell. In three parts divided, coming out from west to east with a long tail, noises were heard in great uproar as if they were rattles.

- The water of the lake seemed to boil, because of the wind that blew. Part of Tenochtitlán was flooded.

- A mourner was heard to lead a funeral dirge to the Aztecs. The Mexica said that it was the goddess Coatlicue, who announced destruction and death to her children, sending Cihuacóatl (later known as La Llorona).

- A strange crane-like bird was hunted. When Moctezuma Xocoyotzin looked into his pupils, he could see unknown men waging war and coming on the backs of deer-like animals.

- Strange people, with one body and two heads, deformed and monstrous, took them to the "house of the black" showed them to Moctezuma, and then disappeared (possibly men on horseback).

The data offered in the Florentine Codex about this legend were written decades after the conquest, approximately in 1555. Modern historians, such as Mateo Respendial, therefore, have concluded that it is possible that some of the events described may have happened, but that it is not proven that Moctezuma truly interpreted these signs as announcing the end of his empire. The idea that these signs were interpreted in this way may have been part of the Franciscan friars' narrative that the conquest of Mejico was part of "God's plan for America", writing stories in which the Indigenous people have already been divinely warned of the arrival of the Spaniards to the continent, an idea formed by friars such as Motolinía, which led to the popular belief in the association between the Spanish captain general Hernan Cortés and the deity Quetzalcóatl.

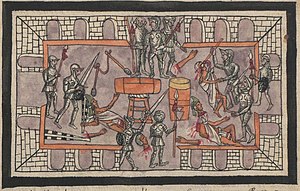

Cortés had to be absent, meeting up with Pánfilo de Narváez in the settlement of Veracruz to increase his forces. Meanwhile, a ceremonyin honor of Huitzilopochtli was to be held in Tenochtitlan. The Mexica asked permission to Captain Pedro de Alvarado, who granted permission to carry out the Tóxcatl feast, which involved extensive rituals and the presence of priests, captains, and young warriors, who danced and sang unarmed. Alvarado discovered serious indications that a conspiracy was underway against the Spaniards, and that in the ceremony the Spaniards would be sacrificed. Alvarado ordered to close the exits, passages and entrances to the patio, and then the massacre began.

It was a great loss for the Aztecs, as the victims were Calmécac-educated leaders, war veterans and calpixques, interpreters of codices. The Spaniards' mere presence offended the Tenochcas, but the respect they felt for Moctezuma was so great no one dared contradict him. The Massacre of the Templo Mayor provoked enormous indignation, and the Mexica threw themselves against the Palace of Axayácatl. Moctezuma asked the tlacochcálcatl (chief of arms) of Tlatelolco, Itzcuauhtzin, to calm the enraged population with a speech in which he asked the Tenochcas and Tlatelolcas not to fight against the Spaniards. The rebellion could not be stopped, the population offended by the attitude of the tlatoani, screamed for rebellion. They besieged the palace for more than twenty days, where the Spaniards barricaded themselves, taking with them Moctezuma and other chiefs.

Back in the city and after a confrontation in Iztapalapa, Cortés was able to meet with his companions in the palace. According to Díaz del Castillo, Cortés had arrived with more than 1,300 soldiers, 97 horses, 80 crossbowmen, 80 riflemen, artillery, and more than 2,000 Tlaxcalans. Pedro de Alvarado held Moctezuma captive, along with some of his sons and several priests. After these events, the death of Moctezuma Xocoyotzin occurred. Fernando de Alva Ixtlilxóchitl affirms it was the Spaniards who murdered Moctezuma, which the Spaniard chroniclers deny. Díaz del Castillo says Moctezuma climbed up one of the palace walls so that he could talk to his people; however, the angry crowd began to throw stones, one of which seriously injured Moctezuma. The tlatoani was taken inside, but died three days later from his wound. Cortés and Moctezuma had created a bond of friendship and the tlatoani, before dying, asked Cortés to favor his son, named Chimalpopoca.

The palace was surrounded, without water or food, and the Tlahtocan (council) chose a brother of Moctezuma, Cuitláhuac, as the new tlatoani. Under these circumstances, Cortés was forced to leave the city. He organized the escape by ordering to load as much gold as possible. To prevent the escape of the Spaniards, the Mexicas had dismantled the bridges over the canals, and Cortés used the beams from the palace to improvise portable bridges. On June 30, 1520, Cortés left Tenochtitlán at night. 80 Tlaxcalan tamemes were to transport the gold and jewels; Sandoval, Quiñones, Acevedo, Lugo, Ordás, Tapia, 200 peons, 20 horsemen, and 400 Tlaxcalans marched ahead. In the center, Cortés, Ávila, Olid, Vázquez de Tapia, the artillery, Malintzin and other indigenous women, Chimalpopoca and his sisters, the Mexica prisoners, and the bulk of the Spanish and allied forces marched. In the rear, Alvarado, Velázquez de León, the cavalry and most of Narváez's soldiers.

Only the first managed to get out, since they were discovered and the alarm was raised, being harassed from canoes, killing some 800 Spaniards and a large number of allies, in addition to losing 40 horses, cannons, harquebuses, swords, bows and iron arrows, as well as most gold. Among the casualties were Captain Juan Velázquez de León, who had been faithful to Cortés despite being a relative of Diego Velázquez de Cuéllar, Francisco de Morla, Francisco de Saucedo, Cacama, two daughters of Moctezuma and Chimalpopoca. Cortés himself was wounded. The survivors escaped by the Tlacopan route, an episode in which the chronicler López de Gómara described Pedro de Alvarado's jump on the Toltacacalopan bridge. All the chroniclers agree with the crying of Cortés on La Noche Triste (the Sorrowful Night).

The route they took to Tlaxcala was through Tlalnepantla, Atizapán, Teocalhueycan, Cuautitlán, Tepotzotlán, Xóloc, Zacamolco. On July 7, the conquistadors were fiercely attacked in the battle of Otumba. Exhausted after days of being chased, and despite the immense inequality of forces, Cortés's military skill focused on defending himself in a circle until he was able to kill the cihuacoatl (main captain) of the Mexicas. Vastly outnumbered, Cortés achieved a victory that is currently studied in all Mejican military academies.

Due to the fact that the greatest number of casualties corresponded to the allied Indians, Cortés thought that the alliance with the Tlaxcalans had ended, but contrary to his prediction, he was received benevolently by the Tlaxcala senate, despite the opposition of Xicohténcatl. The Spanish forces began to reorganize, although it took more than a year to return to take the place of Tenochtitlan. Meanwhile, a smallpox epidemic broke out in Tenochtitlan. As collateral damage, there was a famine due to the disruption of the supply systems. Cuitláhuac ordered the reconstruction of the main temple, reorganized the army and sent it to the Tepeaca valley. He tried to make an alliance with the Purépechas, but their cazonci, Zuanga, refused to accept it. Emissaries were also sent with the intention of sealing peace with Tlaxcala, but they refused. In November of that year, Cuitláhuac died of smallpox. Considering that Cacama had died during the events that occurred on June 30, the Triple Alliance had new successors, Coanácoch in Texcoco, Tetlepanquetzaltzin in Tlacopan and Cuauhtémoc, nephew of Moctezuma Xocoyotzin, in Tenochtitlan.

During his journey to the Great Tenochtitlán, Cortés had achieved the alliances of towns subjugated by the Aztecs, such as Tlaxcala and Chalco. After having gathered his forces and those of his allies, Cortés began the march back to Tenochtitlán in January 1521, more than six months after his retreat. The Aztecs were now governed by Cuauhtémoc, since Cuitláhuac had died due to smallpox, a disease of which some Spaniards were carriers and to which many Indians were extremely vulnerable. In March, Cortés began the siege of the city, to which he cut off the water supply and the basic resources of sanitation, communication, and commerce. Despite his alliances with Texcoco and Tlacopan, the city had to surrender on August 13, marking the beginning of Spanish rule.

Cuauhtémoc, Aztec leader, was arrested after attempting to escape on a raft on Lake Texcoco. Imprisoned in Coyoacán, he was subjected to torture by the Spanish - his feet were burned to make him confess the location of the Aztec treasure. Despite his suffering, he refused to reveal the location, demonstrating great courage and loyalty to his people. Cuauhtémoc was eventually released by the Spanish, but remained under their control as a puppet ruler. In 1525, he became a Catholic convert, taking the name of Carlos, in honor of the Spanish king, and the surname “Guatemocín de Santiago”. He would become an important part of the local bureaucracy, as he retained his noble status and wealth, and was able to bring the native population closer to the Spaniards and the Catholic faith. He would become the Count of Guatemocín, and would die in 1537 of smallpox.

In 1525, several indigenous leaders were found guilty of leading a rebellion against the Spanish. They were hanged in the town square of what is now Mejico City, marking the end of Aztec resistance to Spanish rule.

The Spanish conquest is well documented from multiple points of view. There are accounts by the Spanish leader Hernán Cortés himself, and multiple other Spanish participants, including Bernal Díaz del Castillo. There are indigenous accounts written in both Spanish and Nahuatl, and pictorial narratives by allies of the Spanish, most prominently the Tlaxcalans, as well as the Texcocans and Huejotzincans, and the defeated Mexica themselves, recorded in the last volume of Bernardino de Sahagún's General History of the Things of New Spain.

The 1521 capture of Tenochtitlan and the immediate founding of the Spanish capital Mejico City on its ruins was the beginning of a 269-year-long colonial era during which Mejico was known as Nueva España (New Spain). Two factors made Mejico a jewel in the Spanish Empire: the existence of large, hierarchically organized Mesoamerican populations that rendered tribute and performed obligatory labor, and the discovery of vast silver deposits in northern Mejico. The Kingdom of New Spain was created from the remnants of the Aztec Empire. The two pillars of Spanish rule were the State and the Catholic Church, both under the authority of the Spanish crown. In 1493, the pope had granted sweeping powers to the Spanish monarchy for its overseas empire, with the proviso that the crown spread Christianity in its new realms. In 1524, King Charles I created the Council of the Indies based in Spain to oversee State power in its overseas territories; in New Spain, the crown established a high court in Mejico City, the Real Audiencia, and then in 1535 created the Viceroyalty of New Spain. The viceroy was highest official of the State. In the religious sphere, the diocese of Mejico was created in 1530 and elevated to the Archdiocese of Mejico in 1546, with the archbishop as the head of the ecclesiastical hierarchy, overseeing Catholic clergy. Castilian Spanish was the language of rulers, and increasingly so the language of the common folk. The Catholic faith was the only one permitted, with non-Catholics, including Jews and Protestants, and Catholics holding unorthodox views, excluding Amerindians, being subject to the Mejican Inquisition, which was established in 1571.

In the first half-century of Spanish rule, a network of Spanish cities was created, sometimes on pre-Columbian sites where there were dense indigenous populations. The capital Mejico City was and remains the premier city, but other cities founded in the 16th century remain important, including Puebla de los Ángeles, Nueva Mérida, Zacatecas, Oajaca, Culiacán, and the port of Veracruz. Cities and towns were hubs of civil officials, ecclesiastics, business, Spanish elites, and mixed-race and indigenous artisans and workers. When deposits of silver were discovered in sparsely populated northern Mejico, now part of the Old North, far from the dense populations of central Mejico, the Spanish secured the region against fiercely resistant Chichimecs, establishing the previously mentioned silver-mining cities of Zacatecas and San Luis de Mesquitique, and developing a network of roads, known as the Camino Real de Tierra Adentro, linking the mining cities with the metropolis of Mejico City, which continued to expand as a population center. The Viceroyalty at its greatest extent included the territories of modern Mejico, the Democratic Republic of Central America, El Salvador, and Costa Rica, and a small portion of the Kingdom of Louisiana. The Viceregal capital Mejico City also administrated the Spanish West Indies (the Caribbean), the Spanish East Indies (the Philippines), and Florida.

The Spanish established their political and economic institutions with Indian or Spanish elites as landholders and tax collectors, and Indians or Mestizos as labor. The Spanish set up a system of Repúblicas, with the República de Indios (Republic of Indians) being established in areas densely populated by Indians, who received land, housing and in such urban centers, churches were to be built for their Christianization. In the República, Spaniards, blacks, mestizos or mulattos could not reside, and the native lands and customs were allowed, as long as they did not contravene the Christian religion or the laws of the State. Among the power ceded to these Republics were the administration of communal property, the collection of taxes, citizen security, regulation of commercial activity, among others.

In order to forcefully extract the maximum amount of labor from Indian workers, the Spanish instituted the encomienda system, granting certain Spaniards the right to tax and exploit local Indians by making them laborers and serfs, granting them lands to cultivate and populate, and keeping them in garrisons to work these lands and convert them to Christianity. The most prestigious encomenderos of this system were the Encomenderos of Coatzacoalcos and those of Ecatepec, who were at once landowners, political intermediaries, landlords, judges, and tax collectors, and held a large number of Indians in this system.

The encomienda gave rise to abuses and violence, to a kind of covert slavery. These behaviors were denounced by some individuals, such as Fray Antonio de Montesinos and Fray Bartolomé de las Casas. Fray Matías de Paz reflected from a Christian point of view while the jurist López de Palaci y Rubios contributed a juridical point of view. Bartolomé de las Casas would come to be attended by Carlos I and Felipe II. In 1512, the denunciation of Fray Montesinos, relative to some abuses of these first encomiendas, provoked the immediate promulgation of the Laws of Burgos that same year, extended a year later, where the labor system in the encoiendas is developed and defined explicitly, with the following rights and guarantees of the Indians and the obligations of encomenderos of fair treatment: work and equitable retribution and that he evangelized the encomendados. However, after the secularization of the Spanish empire, these obligations were omitted, transforming the encomienda into a system of forced labor for the native peoples in favor of the encomenderos. On December 9, 1518, this law was enriched by establishing that only those Indians who did not have sufficient resources to earn a living could be encomendados, and that when they were able to fend for themselves, they would cease the encomienda. The laws went so far as to oblige them to teach the Indians to read and write.

In 1527 a new law was passed that determined that the creation of any new encomienda must necessarily have the approval of the religious, who were responsible for judging whether an encomienda could help a specific group of Indians to develop, or whether it would be counterproductive. In 1542, Carlos I, after 50 years of existence of the encomienda, considered that the Indians had acquired sufficient social development for all to be considered subjects of the Crown like the rest of Spaniards. For this reason, the Leyes Nuevas (New Laws) were created in 1542, where it was stated that:

- New encomiendas will not be assigned, and the already existing ones will have to die necessarily with their owners.

- Those encomiendas that were in favor of members of the clergy, public officials, or persons without a conquest title were abolished.

- The amount of the tributes that had to satisfy the entrusted ones is limited considerably.

- That there was no cause or reason to make slaves; that the existing Indian slaves were to be set free, if the full right to keep them in that state was not shown.

The new viceroys arrived in the Americas with express orders that these laws were to be complied with, the opposite of what had happened with the previous ones. There were two wars in Peru between the encomenderos and those loyal to the king in 1544 and 1553. Meanwhile, in New Spain, Viceroy Luis de Velasco y Ruiz de Alarcón freed 15,000 Indians. It also provoked a conspiracy headed by the son of Hernán Cortés, Martín Cortés, II Marqués del Valle and his brother, whose outcome was his perpetual banishment from the Indies.

The rich deposits of silver, particularly in Zacatecas and Guanajuato, resulted in silver extraction dominating the economy of New Spain. Mejican silver pesos became the first globally used currency. Taxes on silver production became a major source of income for the Spanish Monarchy. Other important industries were the agricultural and ranching haciendas and mercantile activities in the main cities and ports. As a result of its trade links with Asia, the rest of the Americas, Africa and Europe, and the profound effect of New World silver, central Mejico was one of the first regions to be incorporated into a globalized economy. Being at the crossroads of trade, people and cultures, Mejico City has been called the "first world city". Trade within the Viceroyalty was conducted through two ports: Veracruz, on the Gulf of Mejico, and Acapulco, on the Pacific Ocean. The Nao de China (Manila Galleons) operated for two and a half centuries, arriving at the latter, carrying products from the Philippines to New Spain, and from there they were transported by land, arriving in Puebla, to Mejico City and Veracruz, from where they would be sent to Spain or to the ports of the Atlantic. Trade contributed to the flourishing of these ports, Mejico City and the intermediate region. Silver and the red dye cochineal were shipped from Veracruz to Atlantic ports in the Americas and Spain; pearls and copper were shipped from the port of La Paz at the southern tip of the San Fulgencio Peninsula to the Philippines and Japan; and silver from the Potosí mining region was carried to Mejico City. Veracruz was also the main port of entry in mainland New Spain for European goods, immigrants from Iberia and Italy, and African slaves. The Camino Real de Tierra Adentro connected Mejico City with the interior of New Spain.

Over the decades, the Viceroys of New Spain would sponsor expeditions towards the north in order to explore the continent, to better understand the geography of New Spain and, most of all, in search of riches, particularly the legendary Seven Cities of Gold. These legends would lead the Spaniards towards the Great Canyon and the Great Plains of North America, coming across a wide variety of peoples and installing outposts in California in the late 16th century, and in the region of Tejas in the mid-17th-century.

The population of Mejico was overwhelmingly indigenous and rural during the colonial period, despite the massive decrease in their numbers due to epidemic diseases and violence. Diseases such as smallpox, measles, and others were introduced by Europeans and African slaves, especially in the 16th century. The indigenous population stabilized around 1-1.5 million individuals in the 17th century from the most commonly accepted 5-30 million pre-contact population. During the two-and-a-half centuries of the colonial era, Mejico received between 700,000-950,000 Europeans, between 180,000 and 220,000 African slaves, and between 50,000 and 140,000 Asians.

The previously-mentioned Bartolomé de las Casas had supported the abolition of the encomienda and the congregation of Indians into self-governing townships, where they would become tribute-paying vassals of the king. He also supported a colonization plan that would be sustainable, which wouldn't rely on resource depletion and Indian labour - Spanish peasants were to migrate en masse to the Americas, where they would introduce small-scale farming and agriculture.

Under Viceroy Martín de Mayorga, the first comprehensive census was created in 1783, with racial classifications included. Although most of its original datasets have reportedly been lost, most of what is known about it comes from essays and field investigations made by scholars who had access to the census data and used it as reference for their works, such as German scientist Alexander von Humboldt. Europeans ranged from 25% to 30% of New Spain's population, Mestizos from 21% to 25%, Indians from to 45% to 54%, and Africans were between 6,000 and 10,000. The total population ranged from 4,799,561 to 7,322,354. It is concluded that the population growth trends of whites and mestizos were even, while the percentage of the indigenous population decreased at a rate of 13%-17% per century, mostly due to the latter having higher mortality rates from living in remote locations and being in constant war with the colonists. Independence-era Mejico eliminated the legal basis for the hierarchical system of racial classification, although the racial/ethnic labels continued to be used.

Colonial law with Spanish roots was introduced and attached to native customs, creating a hierarchy between local jurisdiction (cabildos) and the Spanish Crown. Upper administrative offices were closed to American-born people, even those of pure Spanish blood (criollos). The administration was based on racial separation. Society was organized in a racial hierarchy, with European-born whites on top, followed by American-born whites, mixed-race persons, and the Indigenous in the middle, and Africans at the bottom. There were formal designations of racial categories. The República de Españoles (Republic of Spaniards) comprised European- and American-born Spaniards, mixed-race castas, and black Africans. The República de Indios (Republic of Indians) comprised the Indigenous populations, which the Spanish lumped under the term indio (indian), a colonial social construct that indigenous groups and individuals rejected as a category. Spaniards were exempt from paying tribute, Spanish men had access to higher education, could hold civil and ecclesiastical offices, were subject to the Inquisition, and were liable for military service when the standing military was established in the late 18th century. Indigenous paid tribute, but were exempt from the Inquisition (as they were seen as neophytes in the faith), indigenous men were excluded from the priesthood; and exempt from military service. Although the racial system appears fixed and rigid, there was some fluidity within it, and the racial domination of whites was not complete. Since the indigenous population of New Spain was so large, there was less labor demand for expensive black slaves than in other parts of Spanish America. In the mid-18th-century, the crown instituted reforms that raised Criollos and Castizos to the same privileges enjoyed by Peninsulares, opening doors to multiple positions in the government, the clergy, commerce and the army. Mestizos and Indigenous peoples also benefitted from these reforms, gaining many civil and political rights, with a few being able to attain grandee status.

The Marian apparition of the Virgin of Guadalupe, said to have appeared to the indigenous San Juan Diego in 1531, gave impetus to the evangelization of central Mejico. The Virgin of Guadalupe became a symbol for American-born Spaniards' (criollos) patriotism, seeking in her a Mejican source of pride, distinct from Spain. Our Lady of Guadalupe was declared to be patroness of New Spain in 1754 by the papal bull Non est Equidem of Pope Benedict XIV.

Spanish military forces, sometimes accompanied by native allies, led expeditions to conquer territory or quell rebellions through the colonial era, including the conquest of the Philippine Archipelago. Notable Amerindian revolts in sporadically populated northern New Spain include the Chichimeca War (1576–1606), Tepehuán Revolt (1616–1620), and the Pueblo Revolt (1680), the Tzeltal Rebellion of 1712 was a regional Maya revolt. Most rebellions were small-scale and local, posing no major threat to the ruling elites. To protect Mejico from the attacks of English, French, and Dutch pirates and protect the Crown's monopoly of revenue, only two ports were open to foreign trade—Veracruz on the Atlantic and Acapulco on the Pacific. Among the best-known pirate attacks are the 1663 Sack of Campeche and 1683 Attack on Veracruz. Of greater concern to the crown was foreign invasion. The Crown created a standing military, increased coastal fortifications, and expanded the northern presidios and missions into Alta California and Tejas. The volatility of the urban poor in Mejico City was made evident in the 1692 riot in the Zócalo. The riot over the price of maize escalated to a full-scale attack on the seats of power, with the viceregal palace and the archbishop's residence attacked by the mob.

Spanish projects for American independence (1783-1788)

During the reign of Charles III, there were discussions and proposals for American independence presented to the monarch. However, it is unclear whether Charles III initially took a position in favor or against these proposals. Nevertheless, it is evident that this was a matter of serious consideration at the highest levels of the Spanish political environment. In 1781, Francisco de Saavedra was sent to New Spain as a royal commissioner to meet with Viceroy Martín de Mayorga and other high authorities. During his visit, Saavedra was struck by the wealth and potential of the viceroyalty but also witnessed the growing discontent among the social classes with the Imperial system of administration. He also noted the resentment of the Criollos towards the more favored Peninsulares, and the potential danger posed by French Louisiana. However, he made a distinction between Louisiana and New Spain, as he saw the first as nothing more than "factories or warehouses of transient traders, filled with troublesome Indians", while the Spanish overseas provinces "are an essential part of the nation separate from the other. There are therefore very sacred ties between these two portions of the Spanish Empire, which the government of the metropolis should seek to strengthen by every conceivable means".

Over the next decade, three different proposals were presented to the monarch: the colonialist proposal of Gálvez, the unionist proposal of Floridablanca, and the autonomist proposal of Aranda. All three proposals emphasized the need for reforms to ensure the survival of the Empire and prevent foreign powers from encroaching on Spanish territory. They were also alarmed by the events that had taken place in the British colonies. Ultimately, the proposal of Pedro de Abarca de Bolea, the Count of Aranda, was chosen over the other two. Aranda's proposal was based on the idea of giving more autonomy to the Spanish overseas provinces while still maintaining their loyalty to the Spanish Crown. He believed that this would address the concerns of the Criollos, and prevent the colonies from violently seeking independence. His proposal was successful in that it helped to ease tensions between the colonies and the metropolis, and contributed to a period of relative stability in the Spanish Empire.

The Count of Aranda proposed the independence of the American dominions from Spain, endowing them with their own structure, and turning them into states, as independent monarchies. He also relies on the reasons of José Ábalos, writing in 1781, and others, but points especially to the potential threat of Louisiana, noting the potential of becoming an "irresistible colossus".

Under this premise, Aranda's proposal was:

"That Your Majesty should part with all the possessions of the continent of America, keeping only the islands of Cuba, Puerto Rico and Jamaica in the northern part and some that are more convenient in the southern part, with the purpose that those serve as a stopover or deposit for Spanish commerce. In order to carry out this vast idea in a way convenient to Spain, three princes should be placed in America: one king of New Spain, the other of Peru, and the other of New Granada, with Your Majesty taking the title of Emperor, and reigning over the rest of the Tierra Firme".

Under some conditions "in which the three sovereigns and their successors will recognize Your Majesty and the princes who henceforth occupy the Spanish throne as supreme head of the family", in addition to "a contribution" from each kingdom, that "their children will always marry" "so that in this way an indissoluble reunion of the four crowns will always subsist", "that the four nations will be considered as one in terms of reciprocal trade, perpetually subsisting among them the closest offensive and defensive alliance".

"...established and closely united these three kingdoms, under the bases that I have indicated, there will be no forces in Europe that can counteract their power in those regions, nor that of Spain, which in addition, will be in a position to contain the aggrandizement of the American colonies, or of any new power that wants to establish itself in that part of the world, that with the islands that I have said we do not need more possessions".

In 1785, Charles III made the decision to appoint his tenth child and fourth son, the Infante Gabriel, as the King of New Spain. This was a significant decision, as New Spain was one of the most important colonies of the Spanish Empire, encompassing present-day Mejico and parts of Central America. The appointment of a royal prince as the King of New Spain was seen as a way to strengthen the ties between the colonies and the metropolis, and to ensure the loyalty of the Criollo elites, who were becoming increasingly restless under the rule of the Peninsulares.

Gabriel was born on 12 May 1752 and was only 33 years old at the time of his appointment. He was the youngest of the Spanish royal family to hold such an important position. Before his appointment, he had served as a military officer and had accompanied his father on various diplomatic missions. Gabriel was described as being intelligent, well-educated, and cultured, with a passion for the arts and sciences. Gabriel arrived on the Americas on 12 December 1788, which was a day of great significance for the people of New Spain, as it was the Feast Day of Our Lady of Guadalupe, the patron saint of Mejico. His arrival was greeted with much fanfare and celebration, as the people of New Spain saw his appointment as a sign of the Spanish commitment to New Spain. Upon his arrival, Gabriel met with the outgoing viceroy and the Archbishop of Mejico City. He spent the next few weeks getting to know the people and the culture of the colony. On 29 December 1788, he was crowned as Gabriel I of New Spain at the Metropolitan Cathedral of Mejico City in a lavish ceremony that was attended by all the high-ranking officials and nobles of the colony. The coronation was a symbol of the king's commitment to the colony and his desire to strengthen the ties between the metropolis and the colony.

Independent era (1788-present)

Early post-Independence (1788-1825)

During his reing, King Gabriel quickly began implementing significant reforms in the capital of his new kingdom, Mejico City. Gabriel's priority was to improve the city's infrastructure, and he started by introducing drainage and sewers to all streets, ensuring that none were left without proper drainage. He then paved all of the streets and installed public lighting to illuminate them at night, established a cleaning and garbage collection service, and had the houses numbered. Gabriel also ordered the beautification of promenades, squares and avenues, and controlled the traffic chaos that had been a problem for years. He introduced rental cars and organized the police service, both during the day and at night, provided by the so-called serenos. He applied a policy of persecution to thieves and murderers, and his government was characterized by the hard hand he used against criminals. As a result of Gabriel's efforts, Mejico City came to be called the City of Palaces, and the example of Mejico City was extended to the other cities of the Kingdom, including Veracruz, Toluca, Guadalajara, San Blas, and Querétaro, all of which benefitted fon Gabriel's infrastructure improvements.

Another of the measures to which his government paid much attention was the improvement of the Intendencias, which led to the promotion of cotton, hemp, silk, and linen cultivation. To improve communication and commercial traffic, Gabriel and Güemes ordered the design and construction of a wide network of modern roads, including the one that went from Mejico City to the port of Veracruz, carrying out engineering works to save ravines and rivers. They also established the General Directorate of Post and Telegraph, creating the first line of telegraph between Mejico City and Veracruz.

Gabriel was interested in indigenous cultures and supported several anthropological expeditions. In 1790, during excavations in the Plaza de Armas, the Aztec Calendar was found. Captain Alejandro Malaspina traveled along the coast of Osolután in San Salvador de Guatemala and later San Francisco de Yerbabuena in the Fulgencines to secure Spanish possessions, causing diplomatic problems with Great Britain. Gabriel also supported Martín de Sessé's expedition to form the Mejican flora. As a promoter of education, he endowed the San Carlos Academy with great and outstanding teachers, created the chairs of mathematics applied to architecture, anatomy in the general hospital and physiology, and in 1793 inaugurated the Museum of Natural History. Gabriel also promoted the opening of Indigenous schools for nobles, known as Calmécacs, which benefitted New Spain's large Indigenous populace.

As the newly appointed King, Gabriel I held audiences for all members of Mejican society, regardless of their social status. This was a significant departure from the norm, as previous viceroys and governors had tended to favor the Peninsulares, who were born in Spain, over the Criollos, who were of Spanish descent but born in the Americas, and the Mestizos and Amerindians, who were of mixed or Indigenous descent. Gabriel's willingness to listen to all members of society gave hope to the Indigenous population of Mejico, as he showed them that he intended to create a society where everyone could participate and that they would be considered fully requal to everyone else. This was a radical departure from the colonial mindset, which had viewed the Indigenous population as inferior and in need of protection and guidance.

His rule was also characterized by a great concern for the well-being of the population, as he ordered many hospitals to be opened, which provided medical care for the poor and the sick. He also ordered the expansion of Mejico City's market hall, which helped to stimulate the local economy and provided opportunities for small businesses to thrive. In addition, Gabriel was concerned about the issue of public hygiene, and he ordered the construction of the first public temazcales, which were a great boon for the populace, both rich and poor. All of these actions were a result of Gabriel's concern to increase the quality of life of his subjects. He recognized that a healthy and prosperous population was essential for the long-term success of the colony, and he was willing to invest in the infrastructure and institutions that were necessary to achieve this goal. Gabriel's rule was therefore marked by a strong commitment to social justice and public welfare, which made him popular with many of his subjects. He would be succeeded by his son, Pedro, in 1808.

At the beginning of his reign, Pedro I faced a coup d'état led by Gabriel de Yermo against his Secretary of State, the Count of Tlascopa, Juan José de Aldama, accused of taking advantage of the imprisonment of King Ferdinand VII of Spain and the subsequent political crisis experienced in New Spain to seize his throne. The Royal Court of Mejico appointed Field Marshal Pedro de Garibay, the highest ranking military officer in New Spain, to deal with the problem. Pedro, Garibay and Aldama formed a kind of triumvirate in which they used acts of extreme rigor against the coup plotters and possible republicans. That same night José Antonio Cristo, war auditor; Azcárate, who remained several months in prison, and the Mercedarian friar Melchor de Talamantes, who died in San Juan de Ulúa, where he had been transferred from the jails of the Inquisition, were apprehended. Gabriel de Yermo, on the other hand, was pardoned at the insistence of King Pedro, and retired to his hacienda, but not before creating a volunteer corps that was named after Pedro I and that the population immediately called "chaquetas", a name that was assigned from then on to the supporters of the crown.

Once the situation in New Spain calmed down, Pedro went on to ratify the decree suspending the payment of tribute by the indigenous peoples and mulattos. Likewise, he prohibited any publication likely to propagate revolutionary ideas among the population, and established special police courts, as well as a Military Junta in the capital of all the intendancies of New Spain.

After the Tumult of Aranjuez and the deposition of his cousin, Charles IV of Spain, in favor of his second cousin once removed, Ferdinand VII, Pedro resolved to receive the Spanish royal family in his kingdom if it were needed. Ferdinand was made a prisoner by Napoleon, giving rise to the Spanish War of Independence. The Abdications of Bayonne received a mixed reaction, with part of the population supporting the Constitutionalism offered by Napoleon and the French, and the other against the dynastic change in Spain, recognizing Ferdinand as Emperor of Spain and the Indies. A two-year civil war broke out between supporters and detractors of Napoleon, led by the priest Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla, which was crushed by Agustín de Iturbide, who gained prominence in Novo-Hispanic politics, became Generalissimo of the army, and was married to Pedro's sister, Infanta María Carlota.

After Ferdinand VII was made a prisoner by Napoleon, the Abdications of Bayonne took place, resulting in a divided response from population of New Spain. Some were drawn to the Constitutionalism offered by Napoleon, which promised a modern and progressive form of government, while others remained staunchly loyal to the traditional monarchy and recognized Ferdinand as the legitimate Emperor of Spain and the Indies. Supporters of Napoleon, also known as Afrancesados and inspired by the Enlightenment ideals, began to rally around local leaders who advocated for social and political reforms, seeking the same thing for New Spain. This faction aimed to weaken the power of the Church and the nobility, promote individual rights, and establish a more inclusive and representative government.

Supporters of the traditional monarchy rallied around local leaders who were vehemently opposed to foreign interference and the deposition of the rightful monarch. Agustín de Iturbide, a rising star of Novo-Hispanic politics, a fervent Fernandist and loyalist, became the charismatic leader of this movement. Together with priest Miguel Hidalgo, a priest with fiery rhetoric, they drew upon the sentiments of national pride and loyalty to the Spanish monarchy, seeking to reinstate Fernando VII and resist the influence of the French and their allies. Additionally, Iturbide's marriage to Infanta María Carlota, King Pedro's sister, solidified his connection to other influential royalist families and provided him with the resources needed to lead an effective resistance.

The two-year civil war saw numerous battles and clashes between the loyalists and the supporters of Napoleon. Agustín de Iturbide's military strategy and his ability to rally his forces under the banner of Ferdinand VII played a pivotal role in the loyalists' efforts to regain control of New Spain. These battles were marked by fierce ideological debates and intense struggles for control over key regions. Iturbide's leadership eventually led to a turning point in the civil war, having won the siege of Veracruz on June 23, 1810, and then the Battle of Córdoba one month after, Iturbide managed to suffocate the rebellion in New Spain, cementing Iturbide's legacy as a hero.

With the victory of the Fernandists in New Spain, efforts were made to extend support to metropolitan Spain. King Pedro recognized the opportunity to strengthen the loyalist cause in the Spanish homeland, which had been under French occupation during the Peninsular War. Empowered by such reinforcements, loyalist forces in Spain saw a significant boost in their capabilities. With Iturbide's strategic insight and the newly arrived forces, the loyalists managed to coordinate their efforts and launch a series of successful campaigns against the French.

In 1809, the Napoleonic government was expelled from Spain due to the combined efforts of Spain and its American colonies, leading to a decisive defeat of the French armies. Through the Treaty of Valençay, Napoleon recognized Ferdinand VII as King of Spain, and the treaty was vehemently supported in the Americas. The Constitution of Cadiz, which had been supported by liberals, was declared null and void, and absolutism was re-established. Once again, Pedro, acting with caution, supported the return of his cousin to the throne, and the recognition of the authority of the Spanish Empire by all the inhabitants of New Spain.

King Pedro's reign marked a departure from the absolutist tendencies that had characterized much of Europe during his era. Unlike Spain, which clung to traditional power structures, Pedro embraced a vision of governance that aimed to modernize his kingdom. Recognizing the need for change, he enacted a series of reforms that would shape the future of the nation. These reforms encompassed a wide spectrum of issues. Pedro championed the protection of private property, a move that not only instilled confidence in the citizenry but also facilitated economic growth. With the assurance of property rights, entrepreneurs and investors felt emboldened to contribute to the nation's economic development.

But his vision extended beyond economic prosperity. He understood the importance of freedom of expression and the power of an informed populace. Thus, he ensured the free press, allowing ideas to flow unrestricted and facilitating the spread of knowledge. This move contributed to an intellectually vibrant society that embraced new ideas and perspectives. Another pivotal aspect of the Petrine Reforms, as they are called, was his endorsement of political pluralism, permitting the formation of political parties and installing universal male suffrage. By granting all adult men the right to vote, Pedro democratized the political process and sought to establish a government that truly represented the will of the people. Tragically, King Pedro's untimely death on July 4, 1823, would prevent him from witnessing this historic event.

Upon Pedro's passing, the mantle of kingship passed to his young heir, an 11-year-old by the name of Gabriel II. Recognizing the exigencies of governance during a monarch's minority, a Regency Council was assembled to steward the kingdom's affairs. The council's composition was an amalgam of sagacious minds drawn from various walks of life, a testament to the complexity of governing a diverse realm during a period of transition. The council's ranks comprised luminaries such as María Teresa, Gabriel's mother, and Carlos José, his uncle. Ecclesiastical representation was realized through the Archbishop of Mejico, Pedro José Fuente, and the Inquisitor General, Francisco García Diego. This was complemented by political voices, including José Mariano de Michelena and Pedro Celestino Negrete, individuals tasked with steering the nation through the delicate tides of governance.

In the course of King Gabriel II's reign, an independentist uprising emerged in the regions of Guatemala and Nicaragua. This dissent, marked by localized rebellions and aspirations for autonomy, posed a direct challenge to the monarchy's authority. In response, Iturbide, a prominent figure noted for his previous involvements, took a decisive role in addressing the unrest. He organized and led forces in campaigns to suppress the insurrections. The year 1824 saw significant clashes between Iturbide's forces and the insurgent groups.

Among these engagements, the Battle of Quetzaltenango stands out as a key confrontation. Taking place in the urban landscape, this battle saw Iturbide's loyalist forces pitted against well-entrenched rebels. Iturbide's tactical acumen and strategic maneuvering contributed to a resounding victory for the loyalists. Additionally, the Siege of Granada marked another pivotal event. This siege, characterized by a protracted struggle, challenged Iturbide's leadership and military expertise. Laying siege to the city, Iturbide's forces confronted the insurgents, eventually quelling their rebellion and restoring order.

Establishment of the House of Bourbon-Iturbide (1825-1857)

As Gabriel II was only a child, and the increasingly-popular Agustín de Iturbide, who had ties to the Bourbon dynasty through his marriage of Infanta Carlota, daughter of King Gabriel I, seemed to be a better and more capable option to take the reins of the country, his Regency Council chose to carry out a non-bloody coup d'état, deposing the child king and establishing Carlota as Queen and Agustín as King of New Spain. They were crowned on 21 September 1825, in a ceremony held in Chapultepec Castle. Thus, he was formally named Agustín I of New Spain, and his first official move as King was to change the name of the nation to Mejico, which received support from the criollos, castizos, mestizos and the indigenous. The House of Bourbon-Iturbide was thus established in Mejico, and it continues to reign until the present day. The deposition of Gabriel II gave rise to a line of legitimists - a monarchist group which advocated for the re-installment of Gabriel II later in his life, and believed in his divine right to rule in New Spain.

The first years after the establishment of Mejico's new dynasty were marked by economic growth, social disorder, and ideological conflict between Conservatives and Liberals throughout the country, primarily in the regions of Central America, which were more liberal and republican-minded, while the rest of the country was more socially conservative and monarchist-leaning in nature. Catholicism remained the only permitted religious faith, and the Catholic Church as an institution retained its special privileges, prestige, and property, standing as a bulwark of Conservatism. The army, another Conservative-dominated institution, also retained its privileges. Former Royal Army General-turned-Emperor Agustín de Iturbide, together with his wife Carlota were seen as beacons of Conservatism, an image which they used to further stabilize their hold on the throne.

Agustín and Carlota were able to secure the loyalty of their subjects through a number of reforms such as the reorganization of the government, the modernization of the Royal Army, the establishment of new universities and educational institutions and favorable newspapers, and the creation of a centralized judicial system. This was seen as a move towards strengthening the power of the monarchy, and as a result, a number of political factions emerged in opposition to it. These included the Republican Party, the Federalist Party, and the Liberal Party, each of which had its own agenda and vision for the country. Despite the opposition, the monarchy managed to remain in power over the course of the century, albeit with a number of changes and reforms.

The years between 1830 and 1843 were a period of significant challenges for the Mejican monarchy, as it faced growing opposition from various political factions and economic pressures. The period saw the rise of a number of influential figures and events that would shape the course of Mejican history. One of the most significant events during this period was the secession of Central America in 1838, which marked the beginning of a prolonged period of instability in the region. Despite this, Agustín and Carlota continued to pursue their vision of a strong, centralized monarchy, and implemented a number of policies aimed at consolidating their power. They continued to invest in the military, creating new regiments and modernizing their equipment, in an effort to stimulate growth and reduce dependence on foreign powers.

Moreover, the monarchy faced internal strife with the outbreak of a revolt in Zacatecas, a key mining region in the country. The uprising erupted in 1835, fueled by discontent over taxation policies and growing frustrations with the central authority's perceived neglect of regional interests. The revolt escalated into a full-blown armed conflict, known as the Zacatecas Revolution, which posed a formidable threat to the stability of the young country. The revolt was short-lived, as Iturbide himself mobilized the army to crush the governor's rebels in the Battle of Zacatecas.

At the same time, the monarchy faced growing opposition from various political factions, including the Republican Party, which advocated for the abolition of the monarchy and the establishment of a democratic government. The Liberal Party, meanwhile, sought to limit the power of the monarchy and promote individual freedoms, civil liberties, and to secularize the country. These factions gained strength in the wake of the Central American secession, the Zacatecan Rebellion, and the resulting economic and political instability, and began to coalesce into a unified opposition movement. The monarchy responded by attempting to quell the growing opposition through a series of political reforms and concessions. Agustín I realized that he needed to address the concerns of the opposing factions to prevent further escalation of tensions and potential threats to the country's stability.

In a landmark move, the Emperor convened a National Assembly in 1836 to address the nation's pressing issues and to provide a platform for representatives from all political factions to voice their concerns and propose solutions. The assembly, while initially met with skepticism by some opposition leaders, became a symbol of the monarch's willingness to engage in democratic practices. During the National Assembly, the opposition put forward their respective demands, which included guarantees of individual rights, religious freedoms, and limitations on the monarchy's power. To address the concerns of the Conservatives, Agustín made efforts to incorporate their input into the decision-making process, creating a council of advisors to provide counsel on crucial matters of state.

The National Assembly became a forum for heated debates, as representatives from different factions clashed over their visions for the country's future. It became evident that achieving consensus would be a challenging task, and the Emperor had to carefully navigate between various political interests. To prevent a full-scale conflict, Agustín emphasized the importance of preserving the monarchy and the Catholic Church as a unifying symbol of the nation's history and identity. As a result of these efforts, through an Imperial Decree, the monarchy was maintained, but some powers were devolved to the legislative bodies, and more power was given to the individual provinces.

During this period, a wave of Catholic missionaries surged into the regions of San Fulgencio and Tejas, playing a crucial role in encouraging the evangelization and pacification of these regions, finally managing to convert the Apaches and Navajos, who had been especially reluctant. The Royal Decree of Graces of 1830 played a pivotal role in facilitating the settlement of these regions with new inhabitants. This decree offered land grants and other incentives to attract European and American immigrants to the New North. Many responded to the call, enticed by the promise of land and opportunities for a better life. This influx of settlers, along with the efforts of the missionaries, helped to solidify Spanish influence in the region and establish a more stable governance structure. As the Indigenous resistance waned, the monarchy was better able to extend its authority and enforce law and order in these territories.

In 1843, under the Liberal government of the newly elected Marquess Herrera de Aculco, gold was discovered in upper San Fulgencio when a group of prospectors stumbled upon a vein of gold near the San Fulgencio River, which gave way to the San Fulgencio Gold Rush and turned San Fulgencio into a proper province in the following year. Word of the Gold Rush spread slowly at first; the earliest gold-seekers were people who lived near the Fulgencines or those who heard the news from ships on the fastest sailing routes from the Fulgencines. The first large group to arrive were several thousand Oregonians who came down the Siskiyou Trail. Next came people from Javay, and several thousand Mejicans, as well as people from Peru and from as far away as Chile, both by ship and overland. By the end of 1843, some 6,000 gold-seekers had come to the Fulgencines. Only a small number traveled overland from the rest of Mejico that year. Some of the "forty-eighters", as the earliest gold-seekers were commonly called, were able to collect large amounts of easily accessible gold - in some cases, thousands of dollars worth each day. Ordinary prospectors averaged daily gold finds worth 10 to 15 times the daily wage of a laborer in central Mejico. A person could work for six months in the gold fields and find the equivalent of six years' wages back home.