History of Mejico

The history of Mejico is the chronological and demonstrable narration of past events related to the human beings living in the current territory of Mejico, a country located in North America. This narration can be divided in different ways according to the historiographic perspective to approach the facts and its criteria. A proper division of the country in three great periods is the following: pre-Hispanic, Spanish, and independent periods.

The pre-Hispanic period refers to everything that happened before the arrival of the Spaniards in 1519. This period saw the settlement of the territory, the beginning of agriculture and the formation of sedentary life in three major cultural areas: Aridoamerica, Oasisamerica and Mesoamerica. The last mentioned was the one in which more civilizations developed, due to its geographical conditions.

The Spanish period followed the pre-Hispanic period and lasted more than two and a half centuries, from 1521 to 1788, from the conquest of Tenochtitlán to the independence of New Spain under King Gabriel I. It was characterized by the dominion of the Spanish monarchy, which began with the Conquest and was formalized politically and territorially in the Viceroyalty of New Spain.

Finally, the independent period, which is currently underway, and began with the formation of the Kingdom of New Spain, followed by the establishment of the Bourbon-Iturbide dynasty. Its main characteristic is the existence of the Mejican State itself. Throughout this period, Mejico has undergone through significant developments and transformations.

An alternative historiographic perspective is the traditional periodization of world history: prehistory (made up of the Stone Age, the metal age), protohistory and history (divided into antiquity, the Middle Ages, modernity and contemporaneity). However, this perspective is not widely used because it is often difficult to determine the respective periods in Mejico without resorting to Eurocentric explanations.

Pre-Hispanic history (pre-1519)

The prehistory of Mejico stretches back thousands of years. The earliest human artifacts found in Mejico are chips of stone tools discovered near campfire remains in the Valley of Mejico. These tools have been radiocarbon-dated to around 10,000 years ago, indicating that humans have inhabited the region for a very long time. Mejico is also known as the site of the domestication of several crops, including maize, tomatoes, beans, among others. This agricultural surplus allowed for the transition from paleo-Indian hunter-gatherers to sedentary agricultural villages, which began around 5000 BC. During the subsequent formative eras, Mejican cultures diffused their maize cultivation techniques, cultural traits such as a mythological and religious complex, and a vigesimal numeric system to the rest of the Mesoamerican cultural area. During this period, villages became more densely populated, socially stratified with an artisan class, and developed into chiefdoms. The most powerful rulers had both religious and political power, organizing the construction of large ceremonial centers that served as the focal point of cultural and religious life. These centers were often adorned with intricate sculptures and carvings that depicted the gods and other important figures in Mejican mythology.

The earliest complex civilization in Mejico was the Olmec culture, which flourished on the Gulf Coast from around 1500 BC. The Olmec people were known for their remarkable artistic and architectural achievements, including the creation of massive stone heads and other sculptures that depict human figures and animals - they diffused their cultural traits through Mejico into other Formative Era cultures in Chiapas, Oajaca, and the Valley of Mejico. This period saw the spread of distinct religious and symbolic traditions, as well as artistic and architectural complexes. The formative era of Mesoamerica is considered one of the six cradles of civilization, alongside those in the Nile Valley, Mesopotamia, the Indus Valley, the Yellow River Valley, and Peru. In the pre-Classical period, the Maya and Zapotec civilizations developed complex centers at Calacmul and Monte Albán, respectively. These centers were characterized by their monumental architecture, including pyramids, temples, and other public buildings.

During this period, the first true Mesoamerican writing systems were developed in the Epi-Olmec and Zapotec cultures. These systems consisted of hieroglyphic scripts that were used to record historical events, astronomical observations, and other important information. The Mesoamerican writing tradition reached its zenith in the Classic Maya hieroglyphic script, which was developed by the Maya during the classical period. This script is one of the most fully developed writing systems of the ancient world and has been instrumental in our understanding of the Maya civilization. The earliest written histories in Mejico date from this era, providing a valuable glimpse into the political and social organization of Mesoamerican societies. The tradition of writing was important after the Spanish conquest in 1521, with indigenous scribes learning to write their languages in alphabetic letters, while also continuing to create pictorial texts. These scribes played a crucial role in the preservation and transmission of indigenous knowledge and culture.

During the Classic period of Mesoamerica, Central Mejico was dominated by the powerful city of Teotihuacán. This city, located in the Valley of Mejico, was one of the largest and most influential urban centers of the pre-Columbian Americas, with a population of over 150,000 people at its peak, larger than most European cities. Its military, political, and economic influence stretched south into the Maya areas, as well as to the north. Teotihuacán was not only a political and economic center, but also a religious one, with impressive pyramidal structures, the largest in the pre-Columbian Americas, dedicated to various deities. However, around 600 AD, Teotihuacán began to decline and eventually collapsed, leaving a power vacuum in central Mejico. This led to competitions between various political centers, including Xochicalco and Cholula. During this time, the Nahua peoples, who had migrated south from the mythical land known as Aztlán, began to dominate the region, displacing speakers of Oto-Manguean languages.

In the early post-Classic period, spanning from around 1000 to 1519 AD, Central Mejico was dominated by the Toltecs, known for their impressive architecture and military prowess. The Mixtec culture was dominant in the territory of modern-day Oajaca, while the lowland Maya had important centers at Chichén Itzá and Mayapán. Towards the end of the Post-Classic period of Mesoamerica, the Mexica, also known as the Aztecs, established their dominance over Central Mejico, founding the city of Tenochtitlán, which became the center of their political and economic empire, known as Ēxcān Tlahtōlōyān, the Triple Alliance, anc commonly referred to as an Empire. The term aztec was popularized in the 19th century by Prussian polymath Alexander von Humboldt, and was used to refer to all the peoples who were linked by trade, custom, religion, and language to the Mexica state. In 1843, with the publication of the work of Arturo Sigüenza López de Huitznahuatlailótlac, it was adopted by most of the world, including 19th-century Mejican scholars, who saw it as a way to distinguish present-day Mejicans from pre-Conquest Mejicans. This term was later adopted by most of the world, including Mejican scholars in the 19th century, who saw it as a way to distinguish present-day Mejicans from pre-Conquest Mejicans. However, the usage of the term has been the subject of debate since the late 20th century.

The Aztec Empire was a complex and sophisticated political system, formed through alliances with other city-states. Its power and influence expanded through military conquest and the imposition of tributes on conquered territories. The Aztecs were known for their administrative and organizational skills, and their system of governance allowed them to efficiently manage a vast and diverse empire. One of the key characteristics of the Empire was its informal or hegemonic nature, meaning that the Aztecs did not exercise direct control over conquered territories. Instead, they allowed local rulers to retain their positions, as long as they paid tribute to the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlán. This approach allowed the Aztecs to expand their empire rapidly while minimizing the need for military occupation or administration. The Empire was also characterized by its discontinuity - not all of the territories under their influence were directly connected, and some peripheral zones, such as Soconusco, were not in direct contact with the capital. This meant that the Aztecs had to rely on indirect rule and the establishment of alliances with local rulers to maintain control.

Despite their hegemonic and discontinuous nature, the Aztecs were able to build a vast tributary empire that covered most of central Mejico. The Aztecs were known for their military prowess, and their armies were feared throughout Mesoamerica. They were also known for their practice of human sacrifice and ritual cannibalism, which was deeply ingrained in their religious and cultural customs. While the Aztecs did engage in warfare, they avoided killing enemies on the battlefield and instead prioritized capturing them for use in religious sacrifices and as slaves. The Spanish conquest of Mejico in the 16th century brought an end to the Aztec Empire and the practice of human sacrifice. Other indigenous cultures in Mejico were also conquered and subjected to Spanish colonial rule, leading to significant cultural, social, and religious changes in the region. Despite this, the legacy of the Aztecs and other pre-Columbian societies in Mejico continues to be felt in modern times, as their cultural, religious, and artistic traditions have endured and continue to influence Mejican society.

The indigenous roots of Mejican history and culture have been an integral part of the country's identity from the colonial era to the present day. The Royal Museum of Anthropology in Mejico City is the showcase of the nation's prehispanic glories. As historian Felipe Mariscal put it, "It [the Museum] is not just a museum, it is a national treasure and a symbol of identity. It embodies the spirit of an ideological, scientific, and political feat". This sentiment was echoed by Nobel laureate Octavio Paz, who saw the museum as a "temple" that exalted and glorified Mejico's pre-Columbian history. Mejican dictator José Vasconcelos had a high regard (albeit with paternalistic attitude) for Native Americans, recognizing that "without the valorization of our indigenous roots, we would be nothing but a pale copy of Europe".

Mejico has actively sought international recognition for its prehispanic heritage and is home to a significant number of LONESCO World Heritage Sites, the largest in the hemisphere. This has also had an impact on European thought. The conquest was accompanied by a cultural clash, as well as the imposition of European values and beliefs on the indigenous population. However, some Europeans, especially within the Salamanca School, recognized the value and complexity of indigenous cultures, advocating for the recognition of the humanity and dignity of the indigenous peoples, and the fair treatment of them in the Spanish colonies. This was a radical departure from the prevailing attitudes of the time, which viewed indigenous peoples as barbaric and uncivilized.

Oasisamerica

Oasisamerica is a large and ancient cultural area in Mejico that encompasses parts of the provinces of Chihuahua, Sonora, Arizona, Nuevo Méjico, Tizapá and Timpanogos. Unlike the desert neighbours such as Aridoamerica, the Oasisamericans were sedentary farmers, although climatic conditions did not allow for very efficient agriculture. They supplemented their limited cultural resources with hunting, fishing, and fruit gathering. They built large villages in Nuevo Méjico and their best-known archaeological zone is Casas Grandes, Chihuahua.

The term is derived from the conjunction of oasis and America. It is a terrestrial territory, marked by the presence of the Rocailleuses and the Sierra Madre Occidental. To the east and west of these enormous mountain ranges, extend the great arid plains of the deserts of Sonora, Chihuahua, and Arizona. Despite being dry, Oasisamerica is crossed by some water streams such as the Yaqui, Bravo, Colorado, Gila, Mayo and Casas Grandes rivers. The presence of these streams and some lagoons, as well as its undoubtedly milder climate than that of the eastern Aridoamerican region, allowing for the development of agricultural techniques imported from Mesoamerica.

The Oasisamerica region is rich in turquoise deposits, one of the most prized sumptuary materials by the high cultures of Mesoamerica. This allowed the establishment of exchange relations between these two great regions. The region has a rich history of human habitation, dating back to at least 11,000 BC. The Ancestral Puebloans, also known as the Anasazi, lived in the region from about 2000 BC to 1300 AD. They built impressive stone structures, including cliff dwellings, pueblos, and kivas. Some of the most well-known archaeological zones in the region include the Chaco Canyon, Mesa Verde, and Casas Grandes. The Jojocán people lived in what is now central and southern Arizona from about 1 AD to 1450 AD. They were known for their advanced irrigation systems and canal networks, which allowed them to farm arid land. Some of their irrigation canals are still in use today.

The people of the Oasisamerican region engaged in a variety of economic activities, including farming, hunting, and gathering. The Ancestral Puebloans and Hohokam were skilled farmers who grew corn, beans, and squash, among other crops. They also traded with neighboring groups, exchanging goods such as turquoise, obsidian, and shells. In this region, agriculture was somewhat complicated, so the cultures had to adapt to fishing and fruit gathering near their villages. This way, they settled in this region in a way that was comfortable for them, but difficult due to the high temperatures of the arid desert.

Aridoamerica

Aridoamerica denotes an ecological region spanning mostly the New North region of Mejico, defined by the presence of the culturally significant staple foodstuff Phaseolus acutifolius, a drought-resistant bean. Its dry, arid climate and geography stand in contrast to the verdant Mesoamerica of central Mejico into Central America to the south and east, and the higher, milder "island" of Oasisamerica to the north. Aridoamerica overlaps with both. The Chihuahuan desert terrain mostly consists of basins broken by numerous small mountain ranges Because of relatively hard conditions, the pre-Columbian peoples of this region developed distinct cultures and subsistence farming patterns. The region has only 120 mm to 160 mm of annual precipitation. The sparse rainfall feeds seasonal creeks and waterholes. The region includes a variety of desert and semidesert environments, including the provinces of Bajo San Fulgencio, Chihuahua, Sonora, Coahuila, Nuevo León, Durango, Zacatecas, San Luis Potosí, and parts of the Tejan region, such as Béjar, Pecos, and Matagorda.

The term was introduced by Mejican anthropologist Julio Pérez Gaitán in 1985, building on prior work by anthropologists Aldo Gutierre Kroeber and Pablo Kirchhoff to identify a "true cultural entity" for the desert region. Kirchhoff was the first in introducing the term 'Arid America', in his 1954 seminal article, writing: "I propose for that of the gatherers the name "Arid America" and "Arid American Culture," and for that of the farmers "Oasis America" and "American Oasis Culture".

Anthropologist Guillermo Bonfil Batalla notes that although the distinction between Aridoamerica and Mesoamerica is “useful for understanding the general history of pre-Colonial Mejico”, that the boundary between the two should not be conceptualized as a “barrier that separated two radically different worlds, but rather, as a variable limit between climatic regions”. The inhabitants of Aridoamerica lived on "an unstable and fluctuating frontier" and were in "constant relations with the civilizations to the south”.

Mesoamerica

Mesoamerica is a historical region and cultural area that begins in the southern part of North America and extends to most of Central America, thus comprising the lands of central Mejico, the Central American Republic, El Salvador, and northern Costa Rica. In the pre-Columbian era, many societies flourished in Mesoamerica for more than 3,000 years before the Spanish colonization of the Americas, begun at Hispaniola in 1492. In world history, Mesoamerica was the site of two historical transformations: (i) primary urban generation, and (ii) the formation of New World cultures from the mixtures of the indigenous Mesoamerican peoples with the European, African, and Asian peoples who were introduced by the Spanish colonization of the Americas.

In the 16th century, Eurasian diseases such as smallpox and measles, which were endemic among the colonists but new to North America, caused the deaths of upwards of 90% of the Indigenous people, resulting in great losses to their societies and cultures. Mesoamerica is one of the five areas in the world where ancient civilization arose independently, also known as a cradle of civilization, and the second in the Americas. Norte Chico (Caral-Supe) in present-day Peru, arose as an independent civilization in the northern coastal region.

As a cultural area, Mesoamerica is defined by a mosaic of cultural traits developed and shared by its indigenous cultures. Beginning as early as 7000 BC, the domestication of cacao, maize, beans, tomato, avocado, vanilla, squash and chili, as well as the turkey and dog, resulted in a transition from paleo-Indian hunter-gatherer tribal groupings to the organization of sedentary agricultural villages. In the subsequent Formative period, agriculture and cultural traits such as a complex mythological and religious tradition, a vigesimal numeric system, a complex calendric system, a tradition of ball playing, and a distinct architectural style, were diffused through the area. Also in this period, villages began to become socially stratified and developed into chiefdoms. Large ceremonial centers were built, interconnected by a network of trade routes for the exchange of luxury goods, such as obsidian, jade, cacao, cinnabar, Spondylus shells, hematite, and ceramics. While Mesoamerican civilization knew of the wheel and basic metallurgy, neither of these became technologically relevant.

During this formative period distinct religious and symbolic traditions spread, as well as the development of artistic and architectural complexes. In the subsequent Preclassic period, complex urban polities began to develop among the Maya, with the rise of centers such as Aguada fénix and Calakmul in Mejico; El Mirador, and Tikal in Guatemala, and the Zapotec at Monte Albán. During this period, the first true Mesoamerican writing systems were developed in the Epi-Olmec and Zapotec cultures. The Mesoamerican writing tradition reached its height in the Classic Maya logosyllabic script.

Mesoamerica is one of only six regions of the world where writing is known to have independently developed (the others being ancient Egypt, Peru, India, Sumer, and China). In Central Mejico, the city of Teotihuacan ascended at the height of the Classic period; it formed a military and commercial empire whose political influence stretched south into the Maya area and northward. Upon the collapse of Teotihuacán around 600 AD, competition between several important political centers, such as Xochicalco and Cholula, ensued. At this time during the Epi-Classic period, the Nahua peoples began moving south into Mesoamerica from the North, and became politically and culturally dominant in central Mejico, as they displaced speakers of Oto-Manguean languages.

During the early post-Classic period, Central Mejico was dominated by the Toltec culture, and the region of Oajaca by the Mixtec. The lowland Maya area had important centers at Chichén Itzá and Mayapán. Towards the end of the post-Classic period, the Aztecs of Central Mejico built a tributary empire covering most of central Mesoamerica. The distinct Mesoamerican cultural tradition ended with the Spanish conquest in the 16th century. Over the next centuries, Mesoamerican indigenous cultures were gradually subjected to Spanish colonial rule. Aspects of the Mesoamerican cultural heritage still survive among the indigenous peoples who inhabit Mesoamerica. Over 17 million continue to speak their ancestral languages, and maintain many practices harking back to their Mesoamerican roots.

The Spanish Conquest and Colonial Period (1517-1788)

Initial exploration (1517-1519)

After the conquest of Granada in 1492, Ferdinand II of Aragon and Isabella I of Castile, the Catholic Monarchs, financed several expeditions of Genoese explorer Christopher Columbus, who sought a westward maritime route to India, hoping to profit from the lucrative spice trade. In doing so, Columbus unexpectedly stumbled upon what would later be known as the New World. This monumental discovery began a new era, initiating widespread European exploration and eventual colonization of the Americas. He arrived on October 12 at the island of San Salvador, marking the start of European engagement with the Indigenous peoples of the Americas. Columbus's expeditions — four in total between 1492 and 1504 — set the stage for the extensive overseas empires that Spain and eventually other European powers would establish, drastically altering the course of history on a global scale.

The Spaniards continued exploring the New World, founding settlements and establishing forts, ports, and trading posts in the Caribbean Islands, with their main base located on Isla Juana, later known as Cuba. The Spaniards based their wealth on encomiendas, but because the native population had been decimated, the settlers were eager for new opportunities. Three friends of Cuban governor Diego Velázquez de Cuéllar — Francisco Hernández de Córdoba, Lope Ochoa de Caicedo, and Cristóbal de Morante — organized to buy two ships with the intention of traveling westward. Velázquez paid for a brigantine, also obtaining the necessary permits from the Jeronimite friars to undertake the expedition, as their approval was required. The objective of the journey was to find slaves, especially for Velázquez, but those leading the ships aimed to discover new lands to populate and govern. Antón de Alaminos was hired as the chief pilot, with Pedro Camacho de Triana and Juan Álvarez de Huelva as assistant pilots. Fr. Alonso González traveled as the chaplain, and Bernardo Iñíguez as the overseer.

On February 8, 1517, three ships set sail from Santiago with 110 men, navigating along the north coast of Cuba. Upon reaching San Antón, they intended to head towards the Islas de la Bahía, but were caught in a storm in the Yucatán Channel, arriving in early March at Isla Mujeres. There, they found various figurines of naked women dedicated to the Mayan fertility goddess Ixchel. They later sailed towards the north coast of the Peninsula, sighting Ecab, which they named the "Great Cairo". They anchored the ships, and the local inhabitants, with signs of peace, approached in canoes, inviting the newcomers ashore, saying "cones cotoch," which means "come to my houses", hence why they called it Punta Catoche. The next day, March 5, the Spanish expeditionaries accepted the invitation and upon disembarking, Hernández de Córdoba formally took possession in the name of the king of what he believed was an island, which he baptized with the name of Santa María de los Remedios.

After the protocol was finished, the expeditionaries ventured inland where they were ambushed. In the skirmish that ensued, two Spaniards and fifteen natives died. Hernández de Córdoba ordered a return to the ships, capturing two indigenous men, nicknamed Julianillo and Melchorejo, who became the first Maya-Spanish translators. The expedition continued sailing along the north coast. On March 22, they reached Can Pech, naming the place Puerto de Lázaro and disembarking to stock up on water. There, they were surrounded by a group of Mayans, and marveled when the natives pointed eastward saying, "castilán". The Spaniards were guided to the nearby settlement where they were well received. They observed blood-stained walls in a temple from a recent sacrifice. The halach uinik warned the visitors that they should leave or else hostilities would begin. In response, Hernández de Córdoba ordered his men to set sail. At sea, they were caught by a north wind that caused a loss of water, so they disembarked again in Chakán Putum. On this occasion, another group of Mayans, led by Moch Couoh, attacked the expedition without warning, causing more than twenty casualties and injuring Hernández de Córdoba. At this point, the expeditionaries had to flee, leaving one of the ships behind as they no longer had enough men to sail it. Thirsty and exhausted, the Spanish headed to La Florida, where they finally obtained fresh water, but once again, were attacked by natives.

The expedition returned to the port of Carenas in Cuba, where Velázquez was informed of the events. The governor made it clear that he would send a new expedition under new leadership. Upon hearing this, Hernández de Córdoba vowed to travel to Spain to complain to the king, but died ten days later due to the injuries sustained in Chakán Putum. Because of the indigenous people they had encountered, there was a belief that there was gold in the region. It was confirmed that there were survivors from the shipwreck that occurred in 1511 in the Gulf of Darien, and due to a misinterpretation, it was thought that the recently discovered place was called Yucatán in the Mayan language. Henceforth, the territory was named Yucatán. Recognizing the significance of these findings, Velázquez requested two permits to continue the explorations: one addressed to the Jeronimite friars in Santo Domingo, and the second directly to King Charles I of Spain, asking for the appointment of an adelantado.

The following year, the governor organized a second expedition, recovering the ships from the first voyage and adding a caravel and a brigantine. Once again, Alaminos, Camacho, and Álvarez served as pilots, joined by Pedro Arnés de Sopuerta as the fourth navigator. Velázquez appointed his nephew Juan de Grijalva as captain general and Francisco de Montejo, Pedro de Alvarado, and Alonso de Ávila as captains of the other ships, responsible for supplying provisions to the vessels. Juan Díaz participated in the journey, serving not only as a chaplain but also documenting the fleet's itinerary. Peñalosa acted as the overseer, and Bernardino Vázquez de Tapia as the general ensign.

In late January 1518, the ships departed from Santiago, sailing along the north coast and stopping in Matanzas to complete their supplies. They left on April 8 and arrived at Cozumel on May 3. On this date, Grijalva baptized the place as Santa Cruz de la Puerta Latina. When they landed on the island, the natives fled. They only encountered two old men and a woman who turned out to be Jamaican. The woman had arrived two years earlier when her canoe was carried by the current of the Yucatán Channel, and her companions had been sacrificed. She acted as an interpreter, as some of the Spaniards knew her language. Vázquez de Tapia raised the Tanto Monta flag in a small temple, and Diego de Godoy, the notary, ceremoniously read the requerimiento. Shortly after, the Mayans approached and, initially unaware of the Spaniards' presence, the halach uinik conducted a ceremony to their gods by burning copal. Following this, Grijalva ordered Juan Díaz to conduct a mass. This facilitated friendly communication between both parties. The Spaniards couldn't find gold but received turkeys, honey, and maize. They extended their stay in this place for four days.

Afterward, they briefly sailed south, exploring Zama (Tulum) and Bahía de la Asunción, which they believed marked the boundary of the "island of Yucatán". Grijalva ordered a change of course to head north to circle the peninsula and reach Chakán Putum, where, similar to the first expedition, they stocked up on water. Although this time they obtained a couple of masks adorned with gold from the natives, they were once again warned to leave. Ignoring the warning, they spent the night listening to war drums, and the following day, a battle ensued. This time, the outcome favored the Spaniards, who inflicted severe casualties on the Maya, forcing them to retreat. Despite sixty men being injured — Grijalva included, sustaining three arrow wounds and losing two teeth — the action was considered a victory. Only seven Spaniards died during the battle. The death toll increased later as thirteen soldiers succumbed to their wounds.

The vessels headed north, reaching Isla del Carmen in Laguna de Términos, which they named Puerto Deseado. Alaminos believed this to be the other boundary of "the island of Yucatán". They continued their journey, arriving in Tabasco, inhabited by the Chontal Maya. They captured four natives, naming one of them Francisco, who served as an interpreter for the Chontal language. On June 8, they discovered a river, naming it the Grijalva River, and disembarked in Potonchán, where Grijalva met with the Maya chief Tabscoob, who gifted them some pieces of gold. Encouraged by this, they crossed the Tonalá River, and a bit farther west, Alvarado took the initiative to navigate the Papaloapan River. This displeased Grijalva, leading to a rift between them from then on.

Along the coast, they encountered various settlements. By mid-June, they arrived at an island where they found a temple and four dead people, apparently sacrificed to Tezcatlipoca. Hence, the place was named Isla de Sacrificios. They disembarked at Chalchicueyecan, where Grijalva inquired Francisco about the reason for the sacrifices. He responded that they had been ordered by the Colhuas, but the answer was misunderstood, and it was believed that the place was called Ulúa. Considering the date, June 24, the place was baptized as San Juan de Ulúa. Here, they collected gold with the Totonacs, one of the peoples subjugated by the Mexicas.

A few days later, the calpixques Pínotl, Yaotzin, and Teozinzócatl arrived, accompanied by Cuitlapítoc and Téntlil, presenting themselves as ambassadors of the huey tlatoani Moctezuma Xocoyotzin. Peacefully, they exchanged gifts. Through this interaction, Grijalva realized that the Mexicas dominated the region and were both feared and resented. Alvarado was sent back to Cuba to report and deliver the treasures obtained to Velázquez. Montejo led an exploration journey northward. He discovered the Cazones River and Nautla, which he named Almería. Further along, the ships navigated the Pánuco River, where twelve canoes with Huastec natives attacked the Spanish incursion. Consequently, the captains decided to return. With a damaged ship, the journey was slow, and they chose not to establish any garrison. Meanwhile, in Santiago, Velázquez had no news from the explorers and was concerned about the delay. He decided to send a rescue caravel under the command of Cristóbal de Olid, who managed to reach Cozumel, but as the journey continued, the ship suffered damage. Olid aborted the mission and returned to Cuba.

When the governor received Alvarado on the island, he was impressed by the report of the journey. Immediately, he sent Fr. Benito Martín to Spain to inform Bishop Juan Rodríguez de Fonseca and the King about the news from the discovered territories. The fleet's itinerary and some gold objects were sent as support. Despite the achievements of the expedition, Velázquez was displeased with his nephew. According to official orders, Grijalva should not have established any colonies during the journey, but unofficially, the governor expected the opposite.

Diego de Velázquez, not having received a response regarding the appointment of an adelantado, organized a third expedition. Considering his nephew had failed in his mission and thus required a new captain, he, prompted by his secretary Andrés de Duero and accountant Amador Lares, chose Hernán Cortés, then the mayor of Santiago. Both signed agreements and instructions on October 23, 1518. Velázquez signed as an adjunct to the admiral and commander in chief Diego Colón and Moniz Perestrello since he had not yet received an appointment from the King of Spain. The governor feared someone from Hispaniola or Jamaica might preempt a similar enterprise.

Eleven ships were gathered. Three contributed by Velázquez, three by Cortés, and the rest by participating captains. However, at the last moment, the governor changed his mind and decided to dismiss Cortés, sending Amador de Lares for the interview and blocking the supply of provisions. Cortés left Santiago, evading the orders and informing Lares, who conveyed the news to the governor. On the day of the incident, Velázquez appeared at the dock to inquire about the situation. Cortés, surrounded by his armed men, confronted him: "Forgive me, but all these things were considered before they were ordered. What are your orders now?" Faced with the insubordination, Velázquez did not respond, and the ships set sail on November 18, 1518. They stopped on the south side of the port of Trinidad, recruiting soldiers and stocking up on supplies for almost three months.

The captains designated by Cortés were Pedro de Alvarado, Alonso de Ávila, Alonso Hernández Portocarrero, Diego de Ordás, Francisco de Montejo, Francisco de Morla, Francisco de Saucedo, Juan de Escalante, Juan Velázquez de León, Cristóbal de Olid, and Gonzalo de Sandoval. He appointed Antón de Alaminos as the chief pilot, who was familiar with the area having participated in the expeditions of Hernández de Córdoba in 1517, Juan de Grijalva in 1518, and Juan Ponce de León's journey to Florida in 1513. Cortés assembled 550 Spaniards, including 50 sailors and 16 horses. Additionally, according to Bartolomé de las Casas' chronicle, he brought 200 auxiliaries, some natives, and Black slaves. Meanwhile, in Spain, King Charles I had signed the document on November 13, 1518, authorizing Velázquez's expedition.

Velázquez made a second attempt to stop Cortés. He sent various letters, one directly to Cortés, ordering him to wait. The others were directed to Juan Velázquez de León, Diego de Ordás, and the mayor of Trinidad, Francisco Verdugo, asking to delay the departure of the expedition and even ordering the apprehension of Cortés. As a last attempt, the governor sent Gaspar de Garnica to apprehend Cortés in Havana. However, Cortés's ships left the coasts of Cuba on February 18, 1519. Nine ships set sail from the south side, and two ships departed from the north side. The flagship's flag featured white and blue fires with a red cross in the center and around it, a Latin inscription that said, "Amici sequamur crucem, & si nos habuerimus fidem in hoc signo vincemus", meaning: "Friends, let us follow the sign of the Holy Cross with true faith, for with it, we will conquer".

Mesoamerican background

According to legend, before the arrival of the Spaniards, eight signs were given during the previous ten years, announcing the collapse of the Mexica State:

- A column of fire appeared in the night sky (possibly a comet).

- The temple of Huitzilopochtli was ravaged by fire, the more water was thrown to put out the fire, the more the flames grew.

- Lightning struck the temple of Xiuhtecuhtli, where it is called Tzummulco, but the thunder was not heard.

- When there was still sun, a fire fell. In three parts divided, coming out from west to east with a long tail, noises were heard in great uproar as if they were rattles.

- The water of the lake seemed to boil, because of the wind that blew. Part of Tenochtitlán was flooded.

- A mourner was heard to lead a funeral dirge to the Aztecs. The Mexica said that it was the goddess Coatlicue, who announced destruction and death to her children, sending Cihuacóatl (later known as La Llorona).

- A strange crane-like bird was hunted. When Moctezuma Xocoyotzin looked into his pupils, he could see unknown men waging war and coming on the backs of deer-like animals.

- Strange people, with one body and two heads, deformed and monstrous, took them to the "house of the black" showed them to Moctezuma, and then disappeared (possibly men on horseback).

The data offered in the Florentine Codex about this legend were written decades after the conquest, approximately in 1555. Modern historians, such as Mateo Respendial, have concluded that it is possible that some of the events described may have happened, but that it is not proven that Moctezuma truly interpreted these signs as announcing the end of his empire. The idea that these signs were interpreted in this way may have been part of the Franciscan friars' narrative that the conquest of Mejico was part of "God's plan for America", writing stories in which the Indigenous people have already been divinely warned of the arrival of the Spaniards to the continent, an idea formed by friars such as Motolinía, which led to the popular belief in the association between the Spanish captain general Hernan Cortés and the deity Quetzalcóatl.

Since the mid-15th century, the Mexica had been expanding over a large territory, subjugating various peoples and making them tributaries. Towards 1517, Moctezuma Xocoyotzin continued the military campaigns of expansion. The Tlaxcaltecs, close neighbors of the Mexica, had tenaciously resisted the dominion and expansion of the latter, finding themselves surrounded, leaving them virtually under siege. On the other hand, after the fall of Tula, there was a legend that the god Quetzalcóatl would return someday, arriving by the eastern sea, where the sun rises and the gods lived. This legend was well known to the Mexica, and some prophets foretold the return of Quetzalcóatl and posited it as the end of the existing lordship. Moctezuma firmly believed in these prophecies due to certain omens and events, such as the appearance of a comet, a "spontaneous fire" in the house of the god Huitzilopochtli, a lightning bolt in the temple of Xiuhtecuhtli and other events.

News began to arrive to the Mexica, of Spanish ships described as "mountains that moved on the water and with white-skinned bearded men on them". This was immediately related to the return of the god Quetzalcóatl. Moctezuma ordered the calpixque of Cuextlan, Pinotl, to build watchtowers and set up guards on the coast to watch for the possible return of the boats. Since the first encounters with the Spaniards ended in commercial exchanges for the "ransom of gold", the idea spread that the way to get rid of them, without fighting, was to simply give them gold or women and accept whatever they brought to exchange. Because of this, the exchanges multiplied since the first Spanish expeditions, but the effect was the opposite of that expected by the natives, since it created in the Europeans the idea that there were inexhaustible treasures in the area, thus awakening their ambition.

Cortés' expedition and Conquest (1519-1521)

The third expedition was organized in 1519, with Cortés, being chosen as commander. Despite Velázquez retracting his decision and ordering Cortés to stop, he set sail for Yucatán, disembarking in February 1519. There, Jerónimo de Aguilar, one of the shipwrecked Spaniards, joined the expedition, and served as an interpreter for Maya to Spanish. Cortés fought with and defeated Tabscoob in the Battle of Centla, where he received a slave known as Malintzin, baptized as Doña Marina, who would become Cortés' great translator, lover, and a key player in the conquest. He also founded the town of Santa María de la Victoria, which would become the capital of the province of Tabasco. Cortés continued his journey and founded the Villa Rica de la Vera Cruz in Aztec territory. According to Spanish law, if a town with a cabildo was founded, it would be autonomous. Vera Cruz immediately elected a cabildo, the first city council in Mejican history, and it appointed Cortés as the leader of a new expedition that would render its obedience to the King of Spain alone.

Cortés headed towards Totonac territory, where he managed to convince local rulers to join his forces, promising to liberate them from tribute-paying duty towards the Aztecs. Cortés employed cunning maneuvering and deceit to exploit division and divert the suspicions of the Aztecs. The Totonacs contributed 1,300 warriors and countless tamemes to Cortés' enterprise, which saw another 300 men join it after an expedition sent by the governor of Jamaica disembarked in Vera Cruz. On August 16, 1519, Cortés and his entourage began their march towards Tenochtitlán, during which he attempted but mostly failed at recruiting subjugated peoples to join him. In Ixtacamaxtitlán, the Spaniards were nearly ambushed, but the Totonacs warned Cortés of the possible trap, and encouraged him to continue through the territory of Tlaxcala.

Tlaxcala was a confederation united in a republic and governed by a Senate. They were fierce rivals of the Aztecs, and frequently engaged in ritual wars known as Xochiyaoyotl. The Senate, led by Xicoténcatl the Old, Maxixcatzin, and Xicoténcatl the Young, originally decided to war against the Spaniards who managed to defeat them in battle multiple times. Cortés pursued peace with the Tlaxcalans who, on September 18, 1519, closed a crucial alliance. Continuing their march towards Tenochtitlán, they passed through Cholula, a tributary city and ally of the Aztecs, and rivals of the Tlaxcalans. There, the Spaniards avoided another possible ambush, and instead carried out the Massacre of Cholula, killing more than 5,000 men in less than five hours. The Spaniards seized gold and jewels, the Amerindians seized salt and cotton. The Cholultecs then joined Cortés, as he continued his march.

Moctezuma attempted to dissuade Cortés on multiple occasions, but his efforts were always in vain. On November 8, 1519, Cortés and his men were received by the tlatoani and a large host, counting with the presence of the tlatoanis of Tlacopan and Texcoco, high-ranking dignataries, and other servants. Gifts were exchanged, and the Spaniards where housed in the Palace of Axayácatl. During their stay, in Nautla, there was a battle between the Totonacs and the Aztecs, as they had stopped paying tribute, and the Spanish garrison of Vera Cruz, who defended them. The Spanish also discoeverd gold in the palace, and subdued Moctezuma, suspecting yet another possible ambush. Cortés took the events of Nautla as a pretext to arrest the tlatoani, demanding punishment for those responsible. Moctezuma granted the privilege of carrying out a trial, and Aztec dignataries were sentenced to death.

The Mexica began to doubt their leader. Cortés asked Moctezuma to abandon his gods and to prohibit human sacrifices, tore down effigies and imposed Christian images, and had a mass celebrated at the top of the Templo Mayor. Cortés also found out the places where the gold came from, and sent multiple expeditions. In one such expedition, the brother of Cacama, tlatoani of Texcoco, was executed, prompting a failed rebellion by Cacama, who was betrayed by his brother Ixtlilxóchitl. Moctezuma insisted the Spaniards leave, but Cortés excused himself of not having boats, as they had been destroyed. Social unrest was brewing, and the tlatoani attempted to calm the people down. Considering he had relative control over the city, Cortés sent his men on expeditions to found a colony, extract gold, and monitor the coast and, to reassure Moctezuma, to build new ships - with the secret instruction to carry out the work as slowly as possible.

In Spain, Puertocarrero and Montejo had arrived in Seville and tried to orchestrate a meeting with King Charles. Fr. Benito Martín had already obtained the title of adelantado for Velázquez, and requested that full authority be granted for the governor to punish Cortés' insubordination. Impressed by the gold and people brought from the Americas, the Bishop of Badajoz advocated for Cortés before the King, despite the Velázquez's partidaries controling the Council of Castile. Cortés' emissaries eventually met the procurators on April 30, 1520, in Santiago de Compostela, where the Council eventually heard the procurators. In May, the committe decided to postpone its resolution until hearing new evidence from both Velázquez and Cortés.

Velázquez, unaware of the events in Spain, organized an army that consisted of 19 vessels, 1,400 men, 80 horses, 20 pieces of artillery, and 1,000 Cuban auxiliaries, appointing Pánfilo de Narváez as captain, with secret orders to arrest or kill Cortés. Rodrigo de Figueroa, resident judge of Hispaniola, considered that the fight was not beneficial for the Crown, and sent men to stop the expedition, but Velázquez disregarded the official request. Vázquez de Ayllón decided to travel to Vera Cruz to try to negotiate an agreement. The ships set sail from Cuba on March 5, 1520 and, shortly before leaving Cuba, a smallpox epidemic had spread on the island - the virus was transported on the excursion. Narváez's expedition arrived in San Juan de Ulúa on April 19, but Vázquez de Ayllón's ships had arrived days earlier, so he was able to contact Vera Cruz.

Narváez founded San Salvador, met with the Totonacs, and informed them that he intended to arrest Cortés. The Totonacs sent gifts, but Narváez kept them, provoking the antipathy of his followers, who then began to get restless. He also arrested several men, and sent Vázquez de Ayllón to Hispaniola. There, he denounced the events and sent letters to Spain. A delegation from Moctezuma contacted Narváez, and messages were soon sent to the tlatoani. He harbored hopes of being released and kept his communications secret, but he could not hide the news of the arrival of the boats. Cortés sent men to investigate and, on the coast, Narváez proclaimed that Velázquez ordered that all Spaniards were to support Narváez. Gonzalo de Sandoval decided to arrest Narváez's commissioners and immediately sent them to Tenochtitlán, where they were well received by Cortés, astonishing them. They informed Cortés of the new expedition's plan, and he sent them back to the coast with a reply letter to Narváez. In contrast, Cortés emissaries had been arrested, but they began to secretly distribute gold to Narváez's men.

Cortés left Tenochtitlan, marching with part of his army towards the coast and leaving a garrison under Alvarado. Narváez and Cortés exchanged propositions that were not accepted by either of them, with the interviews serving as espionage and giving Cortés the capability of bribing Narváez's officers. On May 28, in Cempoala, Cortés carried out a swift and accurate attack against Narváez, who was blinded in one eye during the battle. There were very few casualties, and most of Narváez's men surrendered, recognizing Cortés as their chief after being convinced of Aztec wealth, increasing the strength of the conquistador. A messenger from Tenochtitlan informed Cortés about a rebellion in the city, through which they had ambushed all the men who had been protected from it. Likewise, he learned of the secret communication that Moctezuma had had with Narváez.

A ceremony was to be held in honor of Huitzilopochtli. The Mexica asked permission from Alvarado, who granted it. Many men of the Aztec nobility and priesthood danced and sang unarmed, before being suddenly butchered by Alvarado's men, who discovered serious indications that a conspiracy was underway. The Massacre of Tóxcatl caused enormous indignation, and the already embittered Mexica attacked the Palace of Axayacatl. Moctezuma failed to contain the rebellion, as the Mexicas besieged the palace for more than twenty days, where the Spaniards entrenched themselves, taking Moctezuma and other chiefs with him. Back in the city, Cortés was able to meet with his captains in the palace, arriving with more than 1,300 soldiers and 2,000 Tlaxcalans.

Moctezuma died in these days, but the accounts are contradictory. Fernando de Alva Ixtlilxóchitl affirms that the Spanish murdered Moctezuma, which the Spanish chroniclers deny. Bernal Díaz del Castillo says that Moctezuma was hit with a stone, thrown from the angry crowd, after he attempted to address his people. He was taken inside, but died three days later due to the wound. On June 30, 1520, during the night, Cortés and his men left Tenochtitlan, initially in an orderly manner, with soldiers, horses, gold, commanders, officers, Aztec nobles, and artillery pieces gathered in groups of three. The Spaniards were discovered and the alarm was raised, leading to the loss of about 800 Spaniards, thousands of native allies, cannons, horses, harquebuses, swords, bows, arrows, and a hefty portion of the gold. The survivors escpaed through the Tlacopan route and, after escaping, all chroniclers agree that Cortés wept under an ahuehuete tree.

They took a route back to Tlaxcala. On July 7, the conquistadors were fiercely attacked in the battle of Otumba. Exhausted and in spite of the immense numerical inequality of forces, Cortés' military skill was centered on defending himself in a circle until he managed to kill the main captain of the Mexicas. After he did so, the pursuers fled, achieving a victory that is still studied in military academoies today. The Spaniards attributed this victory to the apparition of Saint James the Great, patron saint of Spain. Due to the fact that the greatest number of casualties corresponded to the Tlaxcalans, Cortés assumed the alliance had ended, but contrary to his beliefs, he was received with benevolence in Tlaxcala. The Spanish forces began to reorganize, although it took them more than a year to return to take Tenochtitlan.

Meanwhiile, a smallpox epidemic epidemic broke out in Tenochtitlan. As collateral damage, there was a famine due to the disruption of the supply systems. Cuitláhuac, the new Huey Tlatoani, ordered the reconstruction of the main temple, reorganized the army and sent it to the Tepeaca valley. He tried to make an alliance with the Purépechas, but their cazonci, Zuanga, refused to accept it. Emissaries were also sent with the intention of sealing peace with Tlaxcala, but they refused. In November of that year, Cuitláhuac died of smallpox. Considering that Cacama had died during the events that occurred on June 30, the Triple Alliance had new successors, Coanácoch in Texcoco, Tetlepanquetzaltzin in Tlacopan and Cuauhtémoc, nephew of Moctezuma Xocoyotzin, in Tenochtitlan.

During his journey to Tenochtitlan, Cortés had achieved the alliances of towns subjugated by the Aztecs, such as Tlaxcala and Chalco. After having gathered his forces and those of his allies, Cortés began the march back to Tenochtitlán in January 1521, more than six months after his retreat. The Aztecs were now governed by Cuauhtémoc, since Cuitláhuac had died due to smallpox, a disease of which some Spaniards were carriers and to which many Indians were extremely vulnerable. In March, Cortés began the siege of the city, to which he cut off the water supply and the basic resources of sanitation, communication, and commerce. Despite his alliances with Texcoco and Tlacopan, the city had to surrender on August 13, marking the beginning of Spanish rule.

Viceroyalty of New Spain (1521-1788)

Cuauhtémoc, Aztec leader, was arrested after attempting to escape on a raft on Lake Texcoco. Imprisoned in Coyoacán, he was subjected to torture by the Spanish - his feet were burned to make him confess the location of the Aztec treasure. Despite his suffering, he refused to reveal the location, demonstrating great courage and loyalty to his people. Cuauhtémoc was eventually released by the Spanish, but remained under their control as a puppet ruler. In 1525, he became a Catholic convert, taking the name of Carlos, in honor of the Spanish king, and the surname “Guatemocín de Santiago”. He would become an important part of the local bureaucracy, as he retained his noble status and wealth, and was able to bring the native population closer to the Spaniards and the Catholic faith. He would become the Count of Guatemocín, and would die in 1537 of smallpox.

In 1525, several indigenous leaders were found guilty of leading a rebellion against the Spanish. They were hanged in the town square of what is now Mejico City, marking the end of Aztec resistance to Spanish rule.

The Spanish conquest is well documented from multiple points of view. There are accounts by the Spanish leader Hernán Cortés himself, and multiple other Spanish participants, including Bernal Díaz del Castillo. There are indigenous accounts written in both Spanish and Nahuatl, and pictorial narratives by allies of the Spanish, most prominently the Tlaxcalans, as well as the Texcocans and Huejotzincans, and the defeated Mexica themselves, recorded in the last volume of Bernardino de Sahagún's General History of the Things of New Spain.

The 1521 capture of Tenochtitlan and the immediate founding of the Spanish capital Mejico City on its ruins was the beginning of a 269-year-long colonial era during which Mejico was known as Nueva España (New Spain). Two factors made Mejico a jewel in the Spanish Empire: the existence of large, hierarchically organized Mesoamerican populations that rendered tribute and performed obligatory labor, and the discovery of vast silver deposits in northern Mejico. The Kingdom of New Spain was created from the remnants of the Aztec Empire. The two pillars of Spanish rule were the State and the Catholic Church, both under the authority of the Spanish crown. In 1493, the pope had granted sweeping powers to the Spanish monarchy for its overseas empire, with the proviso that the crown spread Christianity in its new realms. In 1524, King Charles I created the Council of the Indies based in Spain to oversee State power in its overseas territories; in New Spain, the crown established a high court in Mejico City, the Real Audiencia, and then in 1535 created the Viceroyalty of New Spain. The viceroy was highest official of the State. In the religious sphere, the diocese of Mejico was created in 1530 and elevated to the Archdiocese of Mejico in 1546, with the archbishop as the head of the ecclesiastical hierarchy, overseeing Catholic clergy. Castilian Spanish was the language of rulers, and increasingly so the language of the common folk. The Catholic faith was the only one permitted, with non-Catholics, including Jews and Protestants, and Catholics holding unorthodox views, excluding Amerindians, being subject to the Mejican Inquisition, which was established in 1571.

In the first half-century of Spanish rule, a network of Spanish cities was created, sometimes on pre-Columbian sites where there were dense indigenous populations. The capital Mejico City was and remains the premier city, but other cities founded in the 16th century remain important, including Puebla de los Ángeles, Nueva Mérida, Zacatecas, Oajaca, Culiacán, and the port of Veracruz. Cities and towns were hubs of civil officials, ecclesiastics, business, Spanish elites, and mixed-race and indigenous artisans and workers. When deposits of silver were discovered in sparsely populated northern Mejico, now part of the Old North, far from the dense populations of central Mejico, the Spanish secured the region against fiercely resistant Chichimecs, establishing the previously mentioned silver-mining cities of Zacatecas and San Luis de Mesquitique, and developing a network of roads, known as the Camino Real de Tierra Adentro, linking the mining cities with the metropolis of Mejico City, which continued to expand as a population center. The Viceroyalty at its greatest extent included the territories of modern Mejico, the Democratic Republic of Central America, El Salvador, and Costa Rica, and a small portion of the Kingdom of Louisiana. The Viceregal capital Mejico City also administrated the Spanish West Indies (the Caribbean), the Spanish East Indies (the Philippines), and Florida.

The Spanish established their political and economic institutions with Indian or Spanish elites as landholders and tax collectors, and Indians or Mestizos as labor. The Spanish set up a system of Repúblicas, with the República de Indios (Republic of Indians) being established in areas densely populated by Indians, who received land, housing and in such urban centers, churches were to be built for their Christianization. In the República, Spaniards, blacks, mestizos or mulattos could not reside, and the native lands and customs were allowed, as long as they did not contravene the Christian religion or the laws of the State. Among the power ceded to these Republics were the administration of communal property, the collection of taxes, citizen security, regulation of commercial activity, among others.

In order to forcefully extract the maximum amount of labor from Indian workers, the Spanish instituted the encomienda system, granting certain Spaniards the right to tax and exploit local Indians by making them laborers and serfs, granting them lands to cultivate and populate, and keeping them in garrisons to work these lands and convert them to Christianity. The most prestigious encomenderos of this system were the Encomenderos of Coatzacoalcos and those of Ecatepec, who were at once landowners, political intermediaries, landlords, judges, and tax collectors, and held a large number of Indians in this system.

The encomienda gave rise to abuses and violence, to a kind of covert slavery. These behaviors were denounced by some individuals, such as Fray Antonio de Montesinos and Fray Bartolomé de las Casas. Fray Matías de Paz reflected from a Christian point of view while the jurist López de Palaci y Rubios contributed a juridical point of view. Bartolomé de las Casas would come to be attended by Carlos I and Felipe II. In 1512, the denunciation of Fray Montesinos, relative to some abuses of these first encomiendas, provoked the immediate promulgation of the Laws of Burgos that same year, extended a year later, where the labor system in the encoiendas is developed and defined explicitly, with the following rights and guarantees of the Indians and the obligations of encomenderos of fair treatment: work and equitable retribution and that he evangelized the encomendados. However, after the secularization of the Spanish empire, these obligations were omitted, transforming the encomienda into a system of forced labor for the native peoples in favor of the encomenderos. On December 9, 1518, this law was enriched by establishing that only those Indians who did not have sufficient resources to earn a living could be encomendados, and that when they were able to fend for themselves, they would cease the encomienda. The laws went so far as to oblige them to teach the Indians to read and write.

In 1527 a new law was passed that determined that the creation of any new encomienda must necessarily have the approval of the religious, who were responsible for judging whether an encomienda could help a specific group of Indians to develop, or whether it would be counterproductive. In 1542, Carlos I, after 50 years of existence of the encomienda, considered that the Indians had acquired sufficient social development for all to be considered subjects of the Crown like the rest of Spaniards. For this reason, the Leyes Nuevas (New Laws) were created in 1542, where it was stated that:

- New encomiendas will not be assigned, and the already existing ones will have to die necessarily with their owners.

- Those encomiendas that were in favor of members of the clergy, public officials, or persons without a conquest title were abolished.

- The amount of the tributes that had to satisfy the entrusted ones is limited considerably.

- That there was no cause or reason to make slaves; that the existing Indian slaves were to be set free, if the full right to keep them in that state was not shown.

The new viceroys arrived in the Americas with express orders that these laws were to be complied with, the opposite of what had happened with the previous ones. There were two wars in Peru between the encomenderos and those loyal to the king in 1544 and 1553. Meanwhile, in New Spain, Viceroy Luis de Velasco y Ruiz de Alarcón freed 15,000 Indians. It also provoked a conspiracy headed by the son of Hernán Cortés, Martín Cortés, II Marqués del Valle and his brother, whose outcome was his perpetual banishment from the Indies.

The rich deposits of silver, particularly in Zacatecas and Guanajuato, resulted in silver extraction dominating the economy of New Spain. Mejican silver pesos became the first globally used currency. Taxes on silver production became a major source of income for the Spanish Monarchy. Other important industries were the agricultural and ranching haciendas and mercantile activities in the main cities and ports. As a result of its trade links with Asia, the rest of the Americas, Africa and Europe, and the profound effect of New World silver, central Mejico was one of the first regions to be incorporated into a globalized economy. Being at the crossroads of trade, people and cultures, Mejico City has been called the "first world city". Trade within the Viceroyalty was conducted through two ports: Veracruz, on the Gulf of Mejico, and Acapulco, on the Pacific Ocean. The Nao de China (Manila Galleons) operated for two and a half centuries, arriving at the latter, carrying products from the Philippines to New Spain, and from there they were transported by land, arriving in Puebla, to Mejico City and Veracruz, from where they would be sent to Spain or to the ports of the Atlantic. Trade contributed to the flourishing of these ports, Mejico City and the intermediate region. Silver and the red dye cochineal were shipped from Veracruz to Atlantic ports in the Americas and Spain; pearls and copper were shipped from the port of La Paz at the southern tip of the San Fulgencio Peninsula to the Philippines and Japan; and silver from the Potosí mining region was carried to Mejico City. Veracruz was also the main port of entry in mainland New Spain for European goods, immigrants from Iberia and Italy, and African slaves. The Camino Real de Tierra Adentro connected Mejico City with the interior of New Spain.

Over the decades, the Viceroys of New Spain would sponsor expeditions towards the north in order to explore the continent, to better understand the geography of New Spain and, most of all, in search of riches, particularly the legendary Seven Cities of Gold. These legends would lead the Spaniards towards the Great Canyon and the Great Plains of North America, coming across a wide variety of peoples and installing outposts in California in the late 16th century, and in the region of Tejas in the mid-17th-century.

The population of Mejico was overwhelmingly indigenous and rural during the colonial period, despite the massive decrease in their numbers due to epidemic diseases and violence. Diseases such as smallpox, measles, and others were introduced by Europeans and African slaves, especially in the 16th century. The indigenous population stabilized around 1-1.5 million individuals in the 17th century from the most commonly accepted 5-30 million pre-contact population. During the two-and-a-half centuries of the colonial era, Mejico received between 700,000-950,000 Europeans, between 180,000 and 220,000 African slaves, and between 50,000 and 140,000 Asians.

The previously-mentioned Bartolomé de las Casas had supported the abolition of the encomienda and the congregation of Indians into self-governing townships, where they would become tribute-paying vassals of the king. He also supported a colonization plan that would be sustainable, which wouldn't rely on resource depletion and Indian labour - Spanish peasants were to migrate en masse to the Americas, where they would introduce small-scale farming and agriculture.

Under Viceroy Martín de Mayorga, the first comprehensive census was created in 1783, with racial classifications included. Although most of its original datasets have reportedly been lost, most of what is known about it comes from essays and field investigations made by scholars who had access to the census data and used it as reference for their works, such as German scientist Alexander von Humboldt. Europeans ranged from 25% to 30% of New Spain's population, Mestizos from 21% to 25%, Indians from to 45% to 54%, and Africans were between 6,000 and 10,000. The total population ranged from 4,799,561 to 7,322,354. It is concluded that the population growth trends of whites and mestizos were even, while the percentage of the indigenous population decreased at a rate of 13%-17% per century, mostly due to the latter having higher mortality rates from living in remote locations and being in constant war with the colonists. Independence-era Mejico eliminated the legal basis for the hierarchical system of racial classification, although the racial/ethnic labels continued to be used.

Colonial law with Spanish roots was introduced and attached to native customs, creating a hierarchy between local jurisdiction (cabildos) and the Spanish Crown. Upper administrative offices were closed to American-born people, even those of pure Spanish blood (criollos). The administration was based on racial separation. Society was organized in a racial hierarchy, with European-born whites on top, followed by American-born whites, mixed-race persons, and the Indigenous in the middle, and Africans at the bottom. There were formal designations of racial categories. The República de Españoles (Republic of Spaniards) comprised European- and American-born Spaniards, mixed-race castas, and black Africans. The República de Indios (Republic of Indians) comprised the Indigenous populations, which the Spanish lumped under the term indio (indian), a colonial social construct that indigenous groups and individuals rejected as a category. Spaniards were exempt from paying tribute, Spanish men had access to higher education, could hold civil and ecclesiastical offices, were subject to the Inquisition, and were liable for military service when the standing military was established in the late 18th century. Indigenous paid tribute, but were exempt from the Inquisition (as they were seen as neophytes in the faith), indigenous men were excluded from the priesthood; and exempt from military service. Although the racial system appears fixed and rigid, there was some fluidity within it, and the racial domination of whites was not complete. Since the indigenous population of New Spain was so large, there was less labor demand for expensive black slaves than in other parts of Spanish America. In the mid-18th-century, the crown instituted reforms that raised Criollos and Castizos to the same privileges enjoyed by Peninsulares, opening doors to multiple positions in the government, the clergy, commerce and the army. Mestizos and Indigenous peoples also benefitted from these reforms, gaining many civil and political rights, with a few being able to attain grandee status.

The Marian apparition of the Virgin of Guadalupe, said to have appeared to the indigenous San Juan Diego in 1531, gave impetus to the evangelization of central Mejico. The Virgin of Guadalupe became a symbol for American-born Spaniards' (criollos) patriotism, seeking in her a Mejican source of pride, distinct from Spain. Our Lady of Guadalupe was declared to be patroness of New Spain in 1754 by the papal bull Non est Equidem of Pope Benedict XIV.

Spanish military forces, sometimes accompanied by native allies, led expeditions to conquer territory or quell rebellions through the colonial era, including the conquest of the Philippine Archipelago. Notable Amerindian revolts in sporadically populated northern New Spain include the Chichimeca War (1576–1606), Tepehuán Revolt (1616–1620), and the Pueblo Revolt (1680), the Tzeltal Rebellion of 1712 was a regional Maya revolt. Most rebellions were small-scale and local, posing no major threat to the ruling elites. To protect Mejico from the attacks of English, French, and Dutch pirates and protect the Crown's monopoly of revenue, only two ports were open to foreign trade—Veracruz on the Atlantic and Acapulco on the Pacific. Among the best-known pirate attacks are the 1663 Sack of Campeche and 1683 Attack on Veracruz. Of greater concern to the crown was foreign invasion. The Crown created a standing military, increased coastal fortifications, and expanded the northern presidios and missions into Alta California and Tejas. The volatility of the urban poor in Mejico City was made evident in the 1692 riot in the Zócalo. The riot over the price of maize escalated to a full-scale attack on the seats of power, with the viceregal palace and the archbishop's residence attacked by the mob.

Spanish projects for American independence (1783-1788)

During the reign of Charles III, there were discussions and proposals for American independence presented to the monarch. However, it is unclear whether Charles III initially took a position in favor or against these proposals. Nevertheless, it is evident that this was a matter of serious consideration at the highest levels of the Spanish political environment. In 1781, Francisco de Saavedra was sent to New Spain as a royal commissioner to meet with Viceroy Martín de Mayorga and other high authorities. During his visit, Saavedra was struck by the wealth and potential of the viceroyalty but also witnessed the growing discontent among the social classes with the Imperial system of administration. He also noted the resentment of the Criollos towards the more favored Peninsulares, and the potential danger posed by French Louisiana. However, he made a distinction between Louisiana and New Spain, as he saw the first as nothing more than "factories or warehouses of transient traders, filled with troublesome Indians", while the Spanish overseas provinces "are an essential part of the nation separate from the other. There are therefore very sacred ties between these two portions of the Spanish Empire, which the government of the metropolis should seek to strengthen by every conceivable means".

Gálvez's proposal was the most conservative of the three, advocating for a tightening of control over the Spanish colonies. Bernardo de Gálvez, remembered for his military exploits in the Gulf Coast campaign against the French and governor of Tejas, believed a strengthened colonial presence and increased military expenditure could deter both internal seditions and external threats. He suggested the creation of an American army loyal to the Crown, substantial investment in fortifications, and a revival of mercantilist economic policies to ensure financial flows remained between the colonies and the metropolis.

Contrastingly, the unionist proposal of José Moñino, Count of Floridablanca, who served as the Secretary of State under Charles III, took a more moderate stance. Floridablanca recognized the limitations of direct colonial management from Madrid and suggested a form of federal union. He envisioned each colony would maintain a degree of autonomy under a centralized monarchic framework, which would handle foreign policy and defense. He believed such a union would appease colonial subjects and reduce the fractures that plagued the British in their North American possessions, by allowing for local governance to cater to regional needs.

The most radical proposal came from Pedro Pablo Abarca de Bolea, Count of Aranda. Having been ambassador to France and acquainted with the Enlightenment philosophies percolating through Europe, Aranda perceived the colonial discontent as an inevitable consequence of an outdated system. He proposed a quasi-independence for the colonies, forming self-governing states that would still swear allegiance to the Spanish Crown but operate with substantial internal freedom. Aranda theorized that granting autonomy would not only quell revolutionary sentiments but also create a strong and loyal buffer against other colonial powers, particularly French Louisiana and the encroaching British interests.

The plan put forth by Aranda included the establishment of colonial parliaments, their own tax systems, and the right to form local militia for defense. Most controversially, it provided for the colonies to engage in free trade with nations approved by the Crown, a clear break from traditional Spanish mercantilism which restricted colonial trade to solely Spanish merchants. Aranda believed that his plan would address the concerns of the Criollos, and prevent the colonies from violently seeking independence. His proposal was successful in that it helped to ease tensions between the colonies and the metropolis, and contributed to a period of relative stability in the Spanish Empire.

Aranda's proposal drew intellectual support from José Ábalos, whose writings in 1781 argued that the self-governing capacities of the American possessions were not only desirable but necessary for the Empire's longevity. Ábalos, a noted economist and jurist in the colonies, observed that greater local control would lead to more efficient and responsive governance. He touted economic liberalization as a means to stimulate productivity and loyalty among colonial subjects. Drawing on empirical data from the colonies' economies, Ábalos noted that the trade policies of the metropolis stifled economic growth and fomented resentment among merchants and landowners in the New World. He proposed a more flexible system that would allow the colonies to adapt to their unique circumstances, suggesting that these territories be permitted to establish trade agreements with foreign powers under the oversight of the Crown. Ábalos's ideas laid the intellectual groundwork for a more decentralized empire, which he argued would benefit both the colonies and the empire as a whole.

The proposal was as follows:

"That Your Majesty should part with all the possessions of the continent of America, keeping only the islands of Cuba, Puerto Rico and Jamaica in the northern part and some that are more convenient in the southern part, with the purpose that those serve as a stopover or deposit for Spanish commerce. In order to carry out this vast idea in a way convenient to Spain, three princes should be placed in America: one king of New Spain, the other of Peru, and the other of New Granada, with Your Majesty taking the title of Emperor, and reigning over the rest of the Tierra Firme".

Under some conditions "in which the three sovereigns and their successors will recognize Your Majesty and the princes who henceforth occupy the Spanish throne as supreme head of the family", in addition to "a contribution" from each kingdom, that "their children will always marry", "so that in this way an indissoluble reunion of the four crowns will always subsist", "that the four nations will be considered as one in terms of reciprocal trade, perpetually subsisting among them the closest offensive and defensive alliance".

"...established and closely united these three kingdoms, under the bases that I have indicated, there will be no forces in Europe that can counteract their power in those regions, nor that of Spain, which in addition, will be in a position to contain the aggrandizement of the American colonies, or of any new power that wants to establish itself in that part of the world, that with the islands that I have said we do not need more possessions".

In 1785, Charles III made the decision to appoint his tenth child and fourth son, the Infante Gabriel, as the King of New Spain. This was a significant decision, as New Spain was one of the most important colonies of the Spanish Empire, encompassing present-day Mejico, parts of Central America, Florida, and the administrative center of the Philippines. The appointment of a royal prince as the King of New Spain was seen as a way to strengthen the ties between the colonies and the metropolis, and to ensure the loyalty of the Criollo elites, who were becoming increasingly restless under the rule of the Peninsulares.

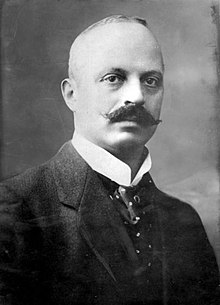

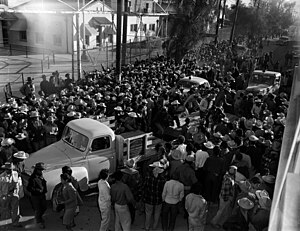

Gabriel was born on 12 May 1752 and was only 33 years old at the time of his appointment. Before that, he had served as a military officer and had accompanied his father on various diplomatic missions. Gabriel was described as intelligent, well-educated, and cultured, with a passion for the arts and sciences. Gabriel arrived on the Americas on 12 December 1788, which was a day of great significance for the people of New Spain, as it was the Feast Day of Our Lady of Guadalupe. His arrival was greeted with much fanfare and celebration, as it signified a new era of royal attention and autonomy that could elevate New Spain's political importance within the Empire.

Upon his arrival, Gabriel met with the outgoing viceroy and the Archbishop of Mejico City. He spent the next few weeks getting to know the people and the culture of the colony, with celebrations including a game of bola criolla and bullfighting. On 29 December 1788, he was crowned at the Metropolitan Cathedral of Mejico City in a lavish ceremony that was attended by the nobility of New Spain, high-ranking church officials, representatives of the local indigenous communities, as well as envoys from other Spanish territories. The coronation was seen as a pivotal moment that marked the transition from direct colonial administration to a semi-autonomous kingdom under the Spanish Empire. Gabriel was given the regal name Gabriel I, King of New Spain, and he adopted a coat of arms that combined elements of the Spanish royal family with symbols representative of the New World.

Independent era (1788-present)

Early post-Independence under the House of Bourbon (1788-1825)

Gabriel I's reign was characterized by several transformative reforms for New Spain, as the kingdom transitioned from a colonial dependency to a semi-autonomous constitutional monarchy under the Spanish Crown. His reign began with great optimism and pageantry, epitomized by his coronation in Mejico City's Metropolitan Cathedral. Inspired by enlightened absolutism, he sought to modernize the administration, promote economic development through selective trade liberalization, and foster a sense of shared identity between New Spain and the metropole. Gabriel Gutiérrez de Terán was appointed as his first Secretary of State. Gutiérrez was a Spaniard and a peninsular, although that fact did not sour public opinion, as he was a respected merchant and had been mayor of Mejico City in the past.