Anglo-Boer War

| Anglo-Boer War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Scramble for Africa | |||||||

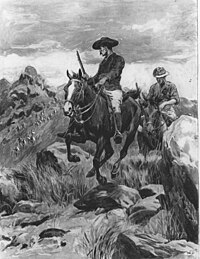

Collapse of the British position in Dreifontein | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

Matabelaland Kingdom |

Limited support and volunteers: | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Sikhombo Mguni King Mlimo |

| ||||||

The Anglo-Boer War (Afrikaans: Vryheidsoorlog, "Freedom War", 8 January 1896 - 20 March 1899), also known as the Boer War and South Africa War, was conflict between the British Empire and the South African Republic over the empire's influence in Southern Africa. Originally founded by Dutch-speaking Boer people dissatisfied with British rule, the South African Republic quickly became an epicenter of wealth and social development in Sub-Saharan Africa, largely as a result of excess gold and diamonds found in the region. Private British entrepreneurs and local colonial governments grew envious of South Africa's influence, and sought after their territory in order to stay ahead of various other European empires who were scrambling for Africa at the time.

The conflict began with a failed attempt by the British to insight an insurrection in South Africa, known as the Jameson Raid. After a full year of failing negotiations and mobilizing military, the war began in earnest on January 11 1897 with a full-scale British invasion of the Transvaal. The British invasions were initially successful at capturing various industrial centers railroads, as well as the port of Maputo which cut off the ZAR from the sea. However, they failed to secure any significant strategic advantage, and by the summer of 1897 the British incursions had completely stalled. With a combination of trench warfare and unconventional guerilla tactics, along with covert foreign support, the Boers dragged on the war for almost two years resulting in many thousands of casualties. Finally, on March 20 1899 the occupation of Maputo was forcefully ended by a Boer offensive supported by the German navy. Seeing the invasion thwarted, Britain agreed to negotiate peace.

While not resulting in any exchange of territory, the war took an enormous toll on both sides. The callous loss of life in an imperial power grab was costly for the Conservative Party in Parliament, and cost the next election for Prime Minister Lord Salisbury. In the South Africa Republic, the wake of devastation took a cost of infrastructure that was never fully recovered from. This led to a negative cycle of economic depression that contributed to the republic's capitulation in forming the Union of South Africa in 1910. Politically, the war united the nation across all political wings against the foreign threat, and propelled Paul Kruger's image from a passive conservative to a national hero. It also contributed to the political career of Louis Botha, promoted to Commandant-General in the middle of the war, who later became the first President of the South African Union. Internationally, the war put a heavy strain on Britain's standing among the Great Powers of Europe, almost igniting war with France as a result of the Fashoda Incident in July of 1898. It was also one of the contributing factors for the diplomatic split between Britain and Germany prior to the the Great War.

The native Africans in Southern Africa had mixed opinions on the war, and was wildly divergent between different African national identities. The Nguni people of Maputo were instrumental for underground resistance against British occupation, and assisted the campaign of Louis Botha to hold the position of Fort Moamba. Many other Africans of Pedi and Swazi descent formed an auxiliary core of 20,000 troops on the side of South Africa. On the other side of the spectrum, the Matabela and Shona people of Zimbabwe took the opportunity to stage a mass insurrection against Boer rule, in a related conflict known as the Second Matabelaland War or the First Chimurenga.

Background

Situation in Transvaal

In the early 1890s, the mass immigration and rapid industrialization was beginning to take its toll on the nation. The rapidly-growing English population were beginning to consolidate a separate national identity, rather than assimilation. The by the election of 1892, the National Party was spreading reports that the Boers were quickly becoming a minority in the nation they themselves founded. Lionel Philips, leader of the Progressive Party, ran unsuccessfully against Kruger for the presidency in the same election. The Progressive Party was overtly pro-imperial, and felt the best outcome for the Transvaal Republic was to be incorporated into the British Empire as an autonomous dominion.

The industrialization of the Transvaal had also introduced an expanding wealth gap between lower class workers and upper class industrialists. The Labour Party took the lead in pushing for social reform, but also began drawing support from both the South African Party and National Party. The Nationals supported social reform because the Boer population tended to be more rural and poorer than English-speaking counterparts. Paul Kruger, however, believed in a more economically conservative policy, and generally ignored the reform movement. While Kruger's conservative views were broadly popular, it was beginning to do some damage to his political position, as the 1892 election only won him 61% of the vote. The Progressive Party seized advantage of this, and stressed that Cape Colony and the British Empire in general were more open to social liberalism.

In the north, the new land obtained in Zimbabwe required closer attention. In October 1893, the First Matabelaland War erupted over a dispute with the Shona people. The ZAR dispatched 800 troops led by Chrstiaan de Wet, supported by 100 African auxiliaries from the Tswana people, to restore order in the territory. In January 1894, King Lobengula was killed and the Matabelaland kingdom was officially dissolved.

Jameson Raid

At this point, some leaders in Cape Colony were secretly planning how they could annex the Transvaal but make it appear to be legal. Cecil Rhodes was elected Prime Minister of Cape Colony in 1890, while he was still Chairman of the British South African Company. Rhodes knew the BSAC wouldn't survive unless they either took control of the diamond mines in Kimberley or the coal fields of Zimbabwe, both of which were sovereign territory of the ZAR. Kruger offered cooperation with Rhodes to construct the Trans-African Railway, and allowed the BSAC to freely operate in Central Africa, but a conflict was still on the horizon. As the ZAR spanned from Namibia all the way to Mozambique, the Company Rule in Zambia was isolated from any other British colony.

The first members of Rhodes' conspiracy was Alfred Beit and Leander Jameson, his financial partners in the BSAC. The Cape Colony Governor Hercules Robinson, and Secretary of the Colonies Joseph Chamberlain, were also involved. Cecil Rhodes' brother, Frank Rhodes, was also a naturalized citizen of Transvaal and a high-ranking member of the Progressive Party. Rhodes secretly reached out to the Progressive Party to offer them a chance in which their goals of a British dominion in Transvaal could be made a reality. The basis of this scheme began with the aborted 1877 plan to annex the ZAR, known as the "Shepstone Plan", which was modified by Rhodes to instead support a popular uprising.

The plan hinged on a belief that the English-speaking population were dissatisfied with the Boer government, and would gladly rise up in favor of British rule. The Progressivists were supposed to insight a revolt in Johannesburg, which would quickly spread throughout the nation among immigrant communities. Once the coup had seized Pretoria, Jameson would be waiting at the border with 1,500 mercenaries of the BSAC, ready to invade the Transvaal in order to "restore order" to the region.

This scheme was doomed from the start, as the English population of Transvaal were (apart from a few exceptions) actually quite content with the republic. The ZAR maintained a fair (Caucasian) franchise, a stable constitution, an independent judiciary, and an acclaimed education system. The idea that the English were a threat to the government, while believed among far-right circles, was purely Nationalist propaganda. While Lionel Philips was definitely cooperating with the Rhodes brothers, it is unlikely that the rest of the Progressive Party was on board with the scheme. As such, preparations for the revolt began to stall.

In December 1895, as Jameson waited on the border, he received a telegram from Philips explaining some of these difficulties, telling him to stand down. Frustrated at this point, Jameson believed he could insight the revolt himself by starting the invasion early. So he crossed the border with 600 men, and made a b-line for Johannesburg. Jameson attempted to cut the telegraph wire to Pretoria, but accidentally cut the wire going to Cape Town instead. Due to that error, the ZAR government was aware of Jameson's invasion the moment they crossed the border. In January 1896, as Jameson's army arrived at Doornkob, he was attacked by the Boer military led by Piet Cronje. After 18 died and 40 wounded, the rest surrendered to Cronje and were taken as prisoners to Pretoria.

Escalation to Conflict

News of the "Jameson Raid" became an immediate scandal across Britain and Cape Colony, and a cause of national alarm for the Boers. The involvement of the BSAC was public knowledge, forcing Rhodes to resign as Prime Minister and Chairman of the company. Evidence involving Robinson and Chamberlain, however, became heavily suppressed. The Liberal party in London was sympathetic to the Boers and discouraged any escalation of conflict. However, many other people of England were viewing Jameson as a public hero. Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany sent a telegram to Kruger shortly after the incident, congratulating him on repelling a foreign incursion. Surprisingly enough, the person most eager to escalate conflict was Kruger himself. Now aware of Britain's intentions, the President knew that war with them was inevitable, but he had to ensure it was the English to make the first move, thereby painting them as the aggressors.

Kruger banned the Progressive Party from future elections, and had all their leaders immediately arrested. They, along with Jameson and members of the raid, were expected to stand trial for high treason, where they could either be sentenced to death or imprisonment. The Cape government issued a demand that the prisoners be extradited to British territory, as stipulated in the Sand River Treaty. Paul Kruger initially rebuffed the demand, stating that the Cape only wants regain their men so they can invade a second time. However, after a few months of standoff Kruger allowed the Jameson party to be released, but still kept the Progressivist leaders in prison.

Kruger's standoff in these negotiations were merely buying time, as the Volksraad issued a mass mobilization of the military. An excess of modern armaments were stockpiled in Pretoria, Bloemfontein and Johannesburg, purchased from their foreign allies like Germany and the United Commonwealth. The federal forces reached the largest in their history, over 60,000 men, in addition to 20,000 auxiliaries from allied African tribes. Ironically, the existential threat to the nation resolved their previous political dissension. Kruger was viewed as the nation's best hope for their defense, and his popularity only improved as the war escalated.

These actions were interpreted by the British as further justification for invasion. Rhodes' acolytes in Cape Colony accused Kruger of violating the Sand River Treaty, and further claimed the suppression of the Progressive Party was silencing the rights of English people. With the relative size and military strength of the ZAR, it was argued that a Boer invasion could conceivably overrun Cape Town before Britain could make a response. The Conservative party in London, including the British Prime Minister, considered that a pre-emptive strike may be necessary to protect the colony. On January 9, 1897, the British Parliament issued an ultimatum to the South African Republic, ordering them to withdraw all their military from the border within 48 hours, or else they will declare war. After the Volksraad failed to respond to this telegram in time, the British declared war on the ZAR on January 11.

Course of the War

British Invasion

Redvers Buller was given command of three divisions, and appointed overall commander of the British forces. Buller's overall strategy involved an eastward invasion that would seize control over the fortified positions in Kimberley and Mafeking, cutting off the ZAR from resources most critical for their economy. From there, they would move up the main railroad line to capture the regional capitals of Bloemfontein and Pretoria. Buller appointed Lord Methuen to lead the siege of Kimberley, and John French to invade through Mafeking. William Gatacre would support with an invasion through the south across the Orange River. Finally, Buller himself would open an extra front invading through Maputo from the east, supported by the Royal Navy.

For the Boers, the Commandant-General Piet Joubert divided the defense of the nation along various possible fronts. Koos de la Rey was stationed in the Orange District to defend the passage leading to Bloemfontein, while Piet Cronje was given overall command of the western front. The eastern front was given to Louis Botha, stationed at Maputo. The north was also a point of concern, as the British might have thought to invade across the Bechuanaland district or Zimbabwe, so this front was put under the command of Christiaan de Wet.

The first clash of military occurred a the Battle of Modder River on January 15, which immediately pushed the Boer defenses back. Kimberley was placed under siege in the following week, whose defenses were under the command of Cornelius Wessel. In the north, Lucas Meyer raised two regiments to defend the fort at Mafeking, a key railroad junction leading towards Pretoria. His intention was to attack the British forces if they attempted to pull south towards Kimberley, but instead they were forced into a long siege.

At sea, the Boers weren't doing much better. What few ships the Boers had, commanded by Adolf Schiel, were outmatched by the Royal Navy commanded by Admiral Percy Scott. The first naval clash occurred on January 30 at the Battle of Inhaca, which was followed by the Battle of Sommerschield in early February. Louis Botha used this time to evacuate military and civilian personnel out of Maputo, recollecting to a more defensible position inland. Following the Battle of Sommerschield, the remaining battleships under Schiel retreated north into the Indian Ocean. With the Boers now cut off by sea, and the British position unassailable, Schiel's navy had no other place to port until the French offered them asylum in the Seychelles.

The British landed in Maputo with little struggle, but soon found resistance the more they pushed inland. The local defensive outpost in Matola was captured by Ian Hamilton in mid-February, consisting of both Boer military and Nguni auxiliaries. William Symons was appointed the military governor of Maputo by Buller, whose priority became suppressing native resistance in the city. Having secured Maputo, Buller pushed inland to assault Botha's center of command at Moamba. This too became a prolonged siege starting in early March.

Second Matabelaland War

At the request of Piet Cronje, most of the regular military was pulled out of Zimbabwe in an attempt to relieve the siege of Mafeking, seeing as a northern front was now unlikely to happen. However, the depletion of military in the north resulted in an entirely new problem. Frustrated by European domination in the region, the Matabela and Shona people staged a mass revolt that seized control over Bulawayo in March of 1897.

Christiaan de Wet was left to deal with the Matabela and Shona uprisings, now with most of his military redeployed to the south. To supplement the low manpower, de Wet impressed local police and mercenaries into the army, largely organized by Benjamin Viljoen. In addition, volunteers of the French Foreign legion also offered to help, commanded by Comte de Villebois-Mareuil. This conflict, known as the Second Matabelaland War or the First Chimurenga, now became a related conflict in the wider Anglo-Boer War. Despite being co-belligerents, it has not ever been proven whether the BSAC or British government had a hand in the native uprising, but it certainly proved to be convenient.

Invasion Stalled, British Setbacks

By April of 1897, it seemed like the Boer defenses were going to crack. Koos de la Rey scored a tactical victory at the Battle of Belmont, but failed to relieve the siege at Kimberley. William Gatacre's division crossed the Orange River in the first week of April, and their push for Bloemfontein was being supported by John French coming from the west. Cecil Rhodes and the British government were confident, up to this point, that the war could reach a resolution within a few months at most. However, it was at this point the war proved to be much harder than it appeared. William Gatacre was crushed by the forces of Koos de la Rey at the Battle of Dreifontein, just within sight of Bloemfontein. Piet Cronje likewise cut off the forces of John French before they could meet up with Gatacre, defeating him at the Battle of Paardeberg. In the east, while Louis Botha was unsuccessful in relieving the Siege of Moamba, he still managed to outmaneuver any further offenses.

These series of defeats right at what appeared to be the cusp of victory had a demoralizing affect on the British military, especially as the Boers were outnumbered in every battle they won. Instead of reaching a resolution to the war in a few months, the conflict had now become a quagmire that the Boers could theoretically carry on indefinitely. The Liberal party in Parliament, opposed to the Conservative government, advocated against dragging the conflict further, and they were now beginning to gain a popular following.

One would wonder how the tiny republic of the ZAR would end up defeating the massive British Empire, effectively reaching a military stalemate by the summer of 1898. It is often assumed that Buller made a strategic blunder getting bogged down in a few sieges, giving the initiative back to the ZAR and giving them time to recover. However, the British military did make frequent attempts for frontal assaults beyond these major strongholds, and after Buller was replaced by Frederick Roberts in January 1898, the situation remained unchanged. Rather, the British loss in the Boer War was the result of tactical deficiencies, not strategic ones. By this time, the British Army had become woefully outdated and inexperienced, as they had not faced a major reform since the Crimean War. Furthermore, Britain's military had become overstretched across their far-flung empire. As the Prime Minister Lord Salisbury warned at the start of the conflict, "We have no army capable of meeting even a second-class Continental Power".

On a fundamental level, the Boer military was designed to have the best advantage in a defensive war. From the original Voortrekkers onward, the Boers adopted guerilla-like tactics that maximized the use of intimate knowledge with local terrain and climate. The Boers were also used to fighting militaries several times their size, after their experience fighting native African kingdoms, and the marksmanship of an average Boar infantry was exceptional compared to their British counterparts. Thus the Boers were not intimidated by the size of their opponent, and combined with their guerilla tactics enabled them to routinely win battles in which they were outnumbered.

Even with these tactics in mind, the fronts of the Anglo-Boer War were often completely stalled with little or no advancement in either direction. The Boers had adopted trench warfare from foreign military advisors, which again gave maximum advantage for a defensive position. While armaments on both sides saw revolutionary advancement in recent years, mobility of infantry was still limited. Life in the trenches rapidly took its toll on both sides, and the experience of military installations near Kimberley and Mafeking was horrific.

In Maputo, the native Nguni tribes were usually allied with the ZAR, who had maintained benevolent treatment and light administration. For this reason, the British occupation of Maputo was constantly threatened by a potential native uprising, and the Africans supplemented Boer hit-and-run attacks against British supply lines. In September 1897, a mass revolt of Nguni in Maputo briefly seized the British encampment, and killed the governor William Symons. This would often force Buller to abandon his position and fall back to the port, because losing Maputo would cause him to become stranded behind enemy lines. This happened so frequently, in fact, that he received the nickname "Sir Reverse" from his political rivals.

International Involvement

By the summer of 1898, Britain's reputation in the international community was in serious danger as a result of their quagmire in South Africa. For many nations, as well as Liberals in Parliament, Britain had violated the sovereignty of the Transvaal by invading first, even if they seemed justified at the time. And as a result of the Boers' tactical success so far, it was becoming a serious possibility that the ZAR could win. The ZAR started seeing many individual volunteers appear from the Netherlands, Germany, and France, either motivated by ideology or sympathy, which continued to spur their morale.

At this point, the French Republic decided to take advantage of Britain's distraction by pushing their own colonial claims in Sudan. Jean-Baptiste Marchland stationed his military in Fashoda on July 10, facing off against the British forces led by Henry Kitchener. Known as the "Fashoda Incident", this compelled Britain to mobilize their military closer at home, for fear of war breaking out with France. As the diplomatic situation escalated, it seemed likely that the Russian and German Empires would likewise join in a conflict against Britain.

Boer Counter-Offensive, War Ends

As Britain was forced to scale down their military in South Africa, the ZAR began slowly gaining ground. Piet Joubert was dismissed as Commandant-General in June 1898, and was replaced by Louis Botha. Focused on the defense of Moamba, Botha appointed Johannes Koch as an overall strategic advisor. Koch developed a new strategy now known as the "Koch Offensive", aimed at dislodging the British from their position. In October 1898, the final resistance in Zimbabwe was crushed, and the leaders of the Second Matabelaland War were executed. As such, the Volksraad was able to redirect their attention from Zimbabwe to the British, and recalled Christiaan de Wet's forces in preparation for the Koch Offensive.

Late in October, the army under Piet Cronje decisively defeated Lord Methuen's forces a the Battle of Kraaipan. Linking up with the remaining forces of Lucas Meyer, this finally brought relief to the Siege of Mafeking. In the same week, the combined forces of Christiaan de Wet and Koos de la Rey stormed the British position at the Battle of Magersfontein, lifting the siege of Kimberley. Then, in January 1899 the siege of Moamba was finally lifted as Lord Roberts was forced to fall back to Maputo. The last major engagement of the war was the liberation of Maputo, putting their brutal occupation to an end. In March 1899, a force of 20,000 Boers closed in on the city, and the remaining British forces withdrew by sea. These series of defeats were known as "Black Week" by the British, and effectively ensured the end of the war.

The Battle of Maputo was, however, partially attributed to outside help. The German Kaiser Wilhelm II considered himself to be a neutral arbitrator in the conflict, and stated his intention to bring Britain's endless war in South Africa to a conclusion. As such, a squadron of German battleships arrived at the shores of Maputo, officially to escort Adolf Schiel's navy back home, but effectively blockaded the port from outside assistance. True to his word, Germany acted as a neutral observer to the peace treaty signed between Britain and the South African Republic in April 1899.

The Treaty of East London was effectively a status quo ante bellum, with the addition of mutual exchange of prisoners and the payment of £SA 3 million to the Transvaal. The apprentice system, although it had long since fallen out of use, was also abolished as it was viewed to be a type of de facto slavery. Additionally, the Progressive Party was permitted back into politics, but with severe limitations on their platform. With the end of resistance in the Central Africa, the trustee territory of Zimbabwe was also incorporated as the seventh district.

See also

- B-class articles

- Altverse II

- Anglo-Boer War

- 1896 in South Africa

- 1897 in South Africa

- 1898 in South Africa

- 1899 in South Africa

- 1890s in the South African Republic

- Conflicts in 1896

- Conflicts in 1897

- Conflicts in 1898

- Conflicts in 1899

- British colonisation in Africa

- Wars involving the South African Republic

- Wars involving the states and peoples of Africa

- Wars involving the United Kingdom

- African resistance to colonialism

- Military history of the British Empire

- Victorian era

- Guerrilla wars

- South Africa–United Kingdom relations

- Wars involving Germany

- Wars involving the Netherlands

- Wars involving Portugal

- Wars involving the United Commonwealth

- 1890s in South Africa

- 1896 beginnings

- 1899 endings