Pueblo Empire

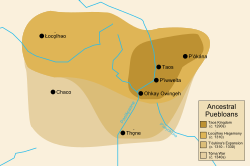

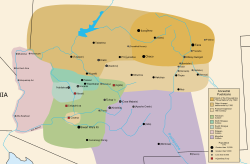

The Pueblo Empire (from the Spanish word Pueblo, meaning village), or “Three Nations” (Taos: Póyuopǫ̏'óne), also known as the Anasazi from the Navajo exonym Anaasází, meaning "ancestors of our enemies", and the Hisatsinom in Hopi, is a nation located in the Southwest. Originally an alliance of three Puebloan ‘'tə̂onemą city-states: Taos, Chaco, and Łocǫ́lhəo, these three city-states expanded to include a domain stretching from the P'aeyok'ona and Paslápaane rivers (Pecos and Rio Grande respectively) in the east to the ʼHakhwata River (Colorado) in the west.

The nation is believed to have been formed around the year 1360, possibly as a response to hostility between the Puebloans and their southern neighbors, including the O'odham. The nation was created after a period of upheaval in Puebloan society, which largely marked the beginning of the "Classical Era" in the region's history. As part of this shift, the Puebloans spearheaded migration into the nation's borders and beyond, which in addition to being the catalyst toward the creation of the Three Nations, led to conflict with other similarly new empires. The youngest of the nation's three components, the "Taos Kingdom", was founded as recently as c. 1300 by the semi-legendary Tə̀ot'́nena (town chief) of the ȉałopháymųp'ȍhə́othə̀olbo (“Red Willows Canyon People”), named Cínemąxína, before being loosely subjugated by Łocǫ́lhəo within a generation of his passing. Around the year 1340 the Tǫ̂mą War broke out, leading to a Chaco-aligned monarch ascending to the throne of Taos. It is believed, however, that by the time of the alliance founding both cities had come under the sway of Łocǫ́lhəo, with the first monarch of the union, Cǫ́ltòbúna, believed to be from this city.

The alliance formed during a turbulent time in the history of the Puebloans and their neighbors. Alongside the rise of the three Puebloan city states, in the south the Hohokam culture (from their O'odham descendants, meaning “those who have gone”) likewise rose to predominance. Namely, the city of Siwañ Wa'a Ki, would become the center of the so-called O'odham Empire. The two empires clashed in a nearly century-long conflict, later dubbed the Hų́łothə́na Wars, during which time networks of heavily defensible fortresses, known as a Hų́łothə́na, were constructed all across the region by both nations. One of these fortresses would develop into the major city of Cíwena, which would topple Siwañ Wa'a Ki for dominance in the Valley of the Sun, which coincided with the Pueblo Empire's dominance in the north.

Etymology

The nation is most commonly known as the Póyuopǫ̏'óne, the “Three Nations”, from the Taos words póyuo (three) and pǫ̏’óna (literally meaning “earth”, but translated as “nations” if plural). Within the nation most of its inhabitants commonly refer to themselves by their particular town or city of origin, for example, inhabitants of Taos originally referred to themselves as “tə̂otho”, meaning “in the village”, when referring to the city, a term from which “Taos” derives from. Additional terms include T’óynemą, which translates to “The People”, from the Taos words t’óy- (“person”) + -nemą (indicates duoplural), or the term “Həotʼóynemą” (“The Canyon People”), which emphasizes the nation’s historical inhabiting of canyons.

By its neighbors the nation is known more commonly by exonyms. The popular term “Anasazi” is derived from the Navajo exonym “Anaasází”, meaning "ancestors of our enemies", as a result of the history of conflict between the two peoples. Descendants or other related peoples of the Ancestral Puebloans prefer the term “Hisatsinom”, a Hopi term meaning “ancient people”.

History

Pre-Formation

Age of Myths during the Great Drought

The late thirteenth century would be marked by a decades-long period of drought, which greatly disrupted the landscape of the region, leading to heavy migration, societal change, and the first conflicts major in an otherwise peaceful region. Many Puebloan settlements were abandoned, with their communities migrating south in search of new lands, and causing conflict with communities in their path. In the cities that remained, there was a cultural shift; the old religious structures, created based on astronomical alignments, were carefully taken apart, with doorways being sealed shut with brick and mortar. Although unsure of the exact reasons for this, later historians have postulated that this shift was in an effort to make amends with nature, by a people whose ancestors, now in command of powerful spiritual power, must have been disrupting and changing the course of nature for the worse. The systematic deconstruction of the old disruptive structures is viewed as a last ditch effort to make amends with a vengeful nature.

From this chaos, several groups emerged, the first being the ȉałopháymųp'ȍhə́othə̀olbo (“Red Willows Canyon People”), who came to inhabit a small town on the banks of the Paslápaane (Rio Grande), and would later become known as simply the Taos. The primary source for the origins of the nation is known as the Łácianątə̂otho, which is dated to a little over a century after the actual events, and commissioned by Taos’ later leaders to chronicle their history. According to this text, Taos’ inception began in a particular Sə̀onp'óna (January), in what is believed to have been the year 1295. This is based on a description that appears later in the text, in which the leader of Taos’ mother is said to have been born thirty-eight years prior to the chronicle’s start, in the presence of a great eclipse, which corresponds to a known astrological event that occurred on 13 June 1257.

The nation’s conception began with a clan dispute “tə̂otho”, meaning “in the village”, which led to the village largely splitting in two. One group is said to have traveled southeast, while another traveled northwest, just as their ancestors had done upon their arrival in the Fourth World countless years before. A young warrior nicknamed Cínemąxína, who earned his nickname of "eye watchman" after losing an eye in a fight, became an unofficial leader of the first group, and under his leadership, a small village was founded known as P'ókána, located about ten miles east of the sacred site of Blue Lake. According to legend, Cínemąxína and a small group of companions continued further to the east, until they encountered wild kònéna (bison) roaming in the plains region beyond their homeland. Running low on food, Cínemąxína is said to have slayed a lone bison single-handedly, before returning to his camp with enough food to feed his followers. Impressed, the village revered the man as a full leader, having been only opposed by a single elder, nicknamed in legend The Disbeliever. To resolve the dispute Cínemąxína led the village on another migration, and only the Disbeliever and his personal family refused to follow.

It is unknown how much of this legend is rooted in fact and how much is later embellishment, embedded into the tale over years of oral tradition. No literary examples have been discovered prior to the Łácianątə̂otho that mention the legend, although scarce mentions of Cínemąxína would eventually appear in texts from neighboring cities around the same time as the nation’s own chronicle. Excavation of Old P'ókána, a site outside the modern day town, has seemingly confirmed sections of the story, with a kiva being discovered that is characteristic of the ones built in Taos during Cínemąxína’s lifetime, and also bearing markings associated with him.

Whatever the case, according to the accounts, in April the group re-entered Taos, with Cínemąxína being declared tə̀ot'́nena (town chief). More importantly, the following month Cínemąxína traveled to the P'ìanwílaną (Picuris Pueblo) of P'iwwelta, a group of a few thousand who inhabited the riverside to the southwest of Tə̂o. Only a few decades prior the Picuris had migrated from Pot Creek (just south of Tə̂o) to their current location. They were notable in that they were one of the only other major villages to speak the Tiwa language like the people of Taos, and had a much more similar culture than that of the nearby Tewa-speaking villages. The two chiefs would declare an eternal pact of friendship, initially just to improve trade and mutual protection against other nearby villages, however, this would unknowingly develop into a significant event in the future of the region.

The alliance would be tested soon after, when in September a conflict erupted against the village of Ohkay Owingeh, after the town suffered a drought and turned to foraging for food near Taos. Both towns come together to subjugate the town, although with very little bloodshed overall. Neither side was particularly skilled in warfare, with historians estimating that the “conflict” was likely fought by unarmored, lightly armed warriors, who mainly sought to intimidate their foe. Later in the year the three villages experienced an increase in population from hûthoną (northerners), who told of a series of hostile tribes (the Numic-speaking peoples) who were pushing south. They were also joined by groups from the west, including the city of Chaco Canyon, where resources were being depleted by a series of droughts and poor harvests.

The small series of communities led by Cínemąxína became one of the few to survive the poor changes in climate and the subsequent migrations, with most nearby villages being abandoned for sites further south, or locations situated near rivers and bodies of water. To prevent a similar disaster from striking as harshly in their territory, the inhabitants of Taos constructed the traditional ditches used to store rain water, but the inhabitants would also augment this method further. This would lead to the town constructing a series of canals from the Paslápaane River (Rio Grande), which ran through the nearby fields and around the town.

At the time of these events in Taos, the Chaco Canyon likely remained one of the most populous cities in the region, despite a net loss in population occurring overall. Historians estimate that it was only eclipsed by a great city to the north (Mesa Verde), which the Taos people named Łocǫ́lhəo (Big Green Canyon), at approximately 22,000 people according to later estimates. Historians note, all three settlements would undergo major projects to help preserve their populations, beginning roughly around the same decade. In the higher altitude mesas, where rainfall was slightly more plentiful, rainwater runoff was captured and ran into irrigation systems. Virtually all major settlements also began employing canal systems, especially those connected to nearby rivers. After nearly overhunting most of the species of the region after recent crop failures, all three settlements began investing in the domesticated turkey more heavily, which would grow into a major food source over the coming decades. Near Taos it is believed that during Cínemąxína's reign certain forests and lands were set aside. Within the private lands, hunting and wood harvesting were forbidden, with the boundaries of the private lands rotating after a certain number of years. This helped to curb the rapid deforestation and overhunting in the region.

In addition to the Puebloans, who inhabited the northern regions, in the southwest resided the Hohokam culture (from their O'odham descendants, meaning “those who have gone”), and in the southeast the Mogollon culture. Within the Hohokam territory and along the fertile Keli Akimel (Gila River), a city emerged that rivaled the Puebloan settlements far to the north. It is believed to have been constructed in the vicinity of the ancient city of “Snaketown”. Once a cultural and economic hub, Snaketown had been almost entirely abandoned after a series of squabbling petty chiefdoms eroded the community, leaving behind one of the most complex irrigation and canal systems in the region. Seeing the potential of the region, a Hohokam group managed to establish a fortress outside the ruins, and by the end of the year managed to pacify or drive off any rival groups around the former city. With the fields of Snaketown at their disposal, the new city took the name of its fortress, becoming the great city of Siwañ Wa'a Ki.

Innovations in the Archaic Era

Because of these rapid changes, historians mark this as the beginning of a new era in regional history, although there is much debate among scholars and historians when exactly the Pueblo III Period ended and the Pueblo IV Period, nicknamed the Classical Era, truly began. One popular notion is to group the crisis period of the late thirteenth century into the former period, placing the early reigns of semi-historical figures like Cínemąxína as the start of the latter period. It is estimated that initially the culture of the Ancestral Puebloans that developed around this time was vastly dissimilar to throughout the thirteenth century. The majority of cities along the Paslápaane (Rio Grande) are believed to have been founded during this period, with archeological evidence telling a similar story to that of the primary sources. In summary: the second year in Cínemąxína’s reign was marked by further population increase in the main settlement of Taos.

Above all else, Tə̀ot'́nena Cínemąxína would make his mark on the region through his extensive use of the town’s resources to invest in greater infrastructure (the sagas describe him as “logistical”, a trait that he likely picked up from experience in early warfare of the time). Specifically during this time the town’s inhabitants (note: sources are quick to specifically credit Cínemąxína with the infrastructural innovation, when more likely it was the work of hundreds of people over the course of years), completed the early water-catching ditches, canals, and other irrigation techniques that would not have been entirely unique within the region. According to anthropologist John Lewis, who worked in the region in the 1960s, based on the estimated manpower of the town at the time and the archeological evidence present, the “old style” irrigation systems were likely completed before 1300, probably within a year or two, and that the “new style” systems began production soon after.

Other historians have argued that due to the city’s location on the river, they likely did not have to worry about additional systems of irrigation as much as other settlements in the region, and thus theorize that the more complex aqueducts did not arrive until much later. It is difficult to definitively say, as over the course of the next three centuries many of these systems would be slowly replaced and upgraded. Additionally there is a debate about who was first to complete an aqueduct in the region: Taos or P'iwwelta. In 1982 the mayor of modern day P'iwwelta argued that their town irrigation system was older, noting that the town was further away from the river initially and thus needed a new system more heavily. This led him to schedule the 600th anniversary celebration of the town earlier, despite differing opinions from historians and the residents of Taos.

Regardless of who was first, it is estimated that the first complex aqueducts in the region began construction sometime between 1290 and 1350, with the consensus being more or less around the year 1300. The sagas specifically mention the event, stating that the people of Taos were heavily cautious after the Great Drought, and sought new ways to ensure that water was abundant, especially after immigration to the region swelled the town’s population. The first aqueducts were likely fairly narrow ditches running from the mountains outside the town down to the edges of the existing irrigation networks. They tapped into mountain springs and melting snow on the peaks, supplying a steady stream of water to the inhabitants down below. Almost immediately it became clear that water seepage and evaporation would more or less negate any effort in a basic canal, leading to the invention of stone-lined canals. Later this was improved further by cutting the groove for the water into one stone. Additionally clay would be used to plug gaps in between stones. It is likely that the first aqueduct took several years to complete and turn into a profitable venture.

According to the primary sources, a large portion of the required labor for these major projects were provided by the newly arrived people from the north and west, who earned a place in the town by contributing to the water supply. It is theorized that these people also likely primarily settled in the more mountainous regions around the town, and eventually the region between Taos and P'iwwelta, as the farmlands between the two towns eventually merged as they expanded (from town center to town center the two towns were only about fifteen miles apart at this time). As another example of forward thinking, the people of Taos also eventually constructed large cisterns, primarily underground, which could collect surplus water for when drought struck. It is estimated that they likely did not come into effect until far after the likes of Cínemąxína, but when water collection eventually far surpassed the town’s use they would have been adequately prepared.

In addition to water management, food production also undoubtedly had to increase to meet demand during this period, especially to offset the decrease in hunting and gathering. Large fields of maize, squash, beans, agave, and other crops sprang up around the town of Taos, with an organizational system eventually springing up. It is unknown when exactly this system was first conceived, or if it occurred during Cínemąxína’s reign at all. By the time of early record creation during the reigns of later rulers, they note that they were continuing the ancient system, implying that it may have first developed around this time. Whoever it was that presided over this creation, is clear that this ruler made a significant alteration in the way land property was typically thought of. Almost all of the new farmland that was purposely created was granted to the ruler of the town, thus for the first time linking a certain amount of income and property to the title itself rather than whichever clan was currently in power. On “royal” land a strict set of rules eventually developed, in which workers were required to supply a heavy cut of their produce and seeds back to the town chief each season in exchange for living on the land.

Outside the state-owned farmland, groups of families living together in a pueblo or cluster or homes were granted plots of land, which were sized roughly proportional to the size of the group, which they were required to work. Eventually these groups would also be required to supply the town with a small portion of their produce as a sort of tax. Alongside this, another form of taxation arised; paying the town through labor. This involved contributing to the nation by helping to construct large infrastructural and architectural projects primarily, in lieu of, or in addition to, produce-based taxation. It is likely that administration was initially slow to start, being enforced initially on the “honor system” due to the town of Taos (or any other towns in the region for that matter) lacking a proper military force.

The warriors of this time were usually assembled to combat raiding from desperate nearby towns, and would be armed with cloth armor, wooden spears, and occasionally shields, helmets, and other rare improvements. Cínemąxína was likely an influence on the warfare of the period, being the first recorded warrior to ascend to a position of power according to records. Taos becomes the destination of many new settlers, but other settlements south of the town also spring up along the rivers. One of the largest to spring up was Cǫ́lʼoma (Bandelier National Monument), just south of Ohkay Owingeh. The town was settled primarily by people from Łocǫ́lhəo (Mesa Verde). The people of Łocǫ́lhəo also began to settle the river just south of the city, the Tàłułi’ína (Grandfather River, OTL San Juan River). As a result the city likely saw a net decrease in population once more, with the city still working to increase his water and food sources to supply its inhabitants, while the region south of Taos became majority Łocǫ́lhəo-born Puebloans.

The city of Chaco, the next largest city in the region, also saw a decrease in population, despite being slightly more prepared. There is evidence that a series of dams and irrigation canals around the city were likely completed around this time, which helped to offset the effects of recent drought. By cross examining several primary sources, all of which vaguely describing the political situation in Chaco, it is believed that there was no central leader at this time. Rather, the various sections of the city acted almost like autonomous communities, with some in fact being fairly distant from the rest. Four town chiefs are known definitively by name; Hȕthócûdena, Pìwxòyłúona, Muuyawmoʼa, and Tòpháy’ȕ, although it is unclear when each leader came to power. The chief Muuyawmoʼa likely had ambitious plans to unite the city, as evidently he would eventually become the city’s first known, sole chief. Additionally, at this time a Muuyawmoʼa is mentioned in the Łácianątə̂otho as the father of Cínemąxína’s second wife, who he possibly married around this time. He had one child from his first marriage, to an unknown woman, his daughter Píanakwíame, who would have been a young child at this time.

As a general migration continued toward the south by the Ancestral Puebloans, historians have noted that major road projects, for the most part, extended in the opposite direction. The most famous of these roads would be the “Great North Road”, which had been built by Chaco, likely centuries before the Great Drought. Near major settlements, the road is known to have extended up to four “lanes”, with stone curbs marking the edge of the road. At certain points along the road’s path, three-feet-tall, curved masonry walls would be erected, in the shape of a “D”, “C”, or horseshoe, with diameters up to thirty feet across, which are believed to have been used to mark changes in direction for those following the road network. Although most of these markers were placed in unsettled areas, evidence of pottery and other items nearby have led historians to postulate that markers also functioned as roadside shrines.

The Great North Road extended north from Chaco, not toward any settlement. Instead the road terminated unceremoniously in the middle of the wilderness. As such, it is believed that the Great North Road and other major road systems, although impressive roads for functional use, were actually intended to guide deceased spirits northward, rather then to be used for everyday people. More practical infrastructure would be built as well, with many major road networks existing in Chaco to link major settlements. Main roads during this period would be about thirty feet wide, with smooth, leveled surfaces made in bedrock, which often connected to large ramps to reach the tops of canyons. A major road in the Taos region was likely created during this time, which would serve as a major highway between Taos, P'iwwelta, and Ohkay Owingeh, running parallel to the Paslápaane.

This trend was less pronounced in Łocǫ́lhəo, where the population had declined from its original high of an estimated 22,000 people earlier in the century. Once renowned for its enormous stone towers and dwellings, the majority of its citizens had migrated to smaller homes in canyon locations, where water sources and farmland were more readily accessible. Much like at Chaco, the city largely became divided into numerous, self-sufficient communities, spread out around the surrounding area. The majority of people once concentrated near the city would begin to inhabit more distant clusters of homes, with the largest cluster of homes having an estimated 1,200 rooms and 200 kivas. From one such district of Łocǫ́lhəo would emerge a leader known as Łàcic’élena, whose name is preserved from a saga written over a century later. His chronicle serves as an important glimpse into the history of the city, even if filtered through the oral tradition of a few generations.

It is said that by the time of his ascension the last tree in Łocǫ́lhəo had been cut down, and the rain had disappeared. The settlements clung to colossal stone towers, which served as defensive watchtowers and fortresses, as the region had largely turned against each other. The most impressive pueblos had stone towers connected to other buildings and rooms with underground tunnels. It is said that as the city slowly disintegrated, the people of Łàcic’élena’s dwelling took up weapons of war, manufactured from the same tools used for building and hunting. They would be armed with stone axes, wooden clubs, and spears, with hide and basket shields also being employed.

Łàcic’élena would be one of many clan leaders who rose to prominence through battle, but perhaps more importantly, gained fame through his distribution of food to his drought-stricken community, which was seen as a greater form of prestige. Łàcic’élena’s chronicle said that on account of his great skill and generosity, his people never resorted to cannibalism. Whether or not this is true, or simply asserted later to make Łàcic’élena appear even nobler, is unknown, but it is known that across all of Łocǫ́lhəo, cannibalism was practiced by the most desperate of people. It is said that Łàcic’élena became ruler of all Łocǫ́lhəo, following a decisive battle against the other clans of the region, but he would truly win over the region when he rallied the region against neighboring city states. He first struck northwest against the Canyon of the Ancients. Next he is said to have retaken Kòki’ínahəo (Crow Canyon), which was the site of a great defeat for his people almost two decades prior.

It is likely that Łocǫ́lhəo survived due to these more aggressive practices of raiding and conquest, extracting tribute of food, water, and timber from its neighbors. Evidence suggests that the city of Łocǫ́lhəo had more friendly relations with the settlements of the Paslápaane, as many of these settlements were founded by the city’s refugees. This also extended to Taos, as commodities such as pottery and products from bison have been discovered in the west of Taos origin. Later, the city would also have ties with Chaco to the south, with roads having been discovered that linked Łocǫ́lhəo to the Great North Road.

Formative Wars

During this time, reign over all of Łocǫ́lhəo was firmly established by Łàcic’élena, with the loyalty of the various districts of the city bought through hefty donations of water and food. Łàcic’élena’s kingdom had been established through fierce raiding and wars of conquest against the surrounding regions, leading to his state being granted the title of the region’s first “empire”, despite directly controlling little territory. Settlements along the southern river (San Juan River) appear to be more closely controlled, as most of the inhabitants of the river were originally settlers from Łocǫ́lhəo. Łàcic’élena would become known as a “P’ȍłòwaʼána”, which roughly translates to “Water Chief”, or “Watergarch” in English, in regards to his powerful control over water sources and distribution. Following his lead, several other town chiefs would adopt his practices, creating various networks of rival warlords, each centered around a source of water or other important resource.

War related tactics quickly spread across the region, as an otherwise peaceful region was forced toward militarism, either to raids their neighbors, or to defend one’s self from other such raiders. The two kingdoms of Łocǫ́lhəo under Łàcic’élena and Taos under Cínemąxína eventually met in the middle near the Tsąmą' ǫŋwįkeyi (Rio Chama), but rather than fighting against each other, the two kingdoms cooperated against the smaller communities of the region. During the lifetimes of both rulers, the two kingdoms would continue to cooperate in matters of trade, creating a well traveled trade route between west and east.

Near the southeast edge of the ʼHakhwata (Colorado) Plateau would emerge the people known to historians as the Sinagua, which were believed to have descended from the Mogollon culture of the southeast, albeit with heavy influence from the Hohokam, who they crossed en route to their new location. Historians postulate that two Sinagua nations formed: the North and South Sinagua, with the southern nation primarily settling the Haka'he:la (Verde River), and the northern nation controlling from that river to the edge of the Paayu (Little Colorado River).

As the people of the north became increasingly militant toward the south, an important development began among the largest nations, from the Sinagua to the Hohokam south of them. Important resources would begin to be secured by constructing defensive structures, which quickly grew to become larger than any previously constructed fortifications in the region. The oldest known such structure would be constructed by the southern Sinagua as a massive cliff dwelling above the Haka'he:la, which the non-Sinagua would later call Kánałó (OTL Montezuma Castle). The fortifications at Kánałó would be heavily upgraded over the next several decades, becoming a vast fortress and seat of power for the Sinagua, eventually inspiring other nearby people to construct fortifications of their own. These vast fortresses would become known as the hų́łothə́na, often translated in English as “castle”. Especially in the southwest, where many nations converged over the rivers of the Valley of the Sun, the hų́łothə́na would become an important part of the region’s history, with many such fortresses coming into being over the century.

Around the year 1310 a leader named Yanauluha would lead a group to settle the Halona Idiwan’a (Middle Place), the homeland of the Zuni, centered at the settlement of Shiwinna. Despite being seen as an easy target for the emerging groups of raider chieftains and watergarchs in the region, Shiwinna would prosper as a careful buffer state being the various powers of the region. The Mogollon and Hohokam people of the south would support the Zuni in an attempt to deter raids from Łocǫ́lhəo, with the Hohokam later constructing a hų́łothə́na southwest of Shiwinna, nicknamed the Petrified House, around the year 1323.

Despite the grandeur and wisdom bestowed upon Cínemąxína by the Łácianątə̂otho, as proposed by his later descendants, other sources report that his reign abruptly ended in failure in the year 1310, with the great later being killed. All sources agree that in that year Łàcic’élena finally broke the peace with Taos and attacked as far as the city itself. Taos purports that Cínemąxína fell in battle defending his homeland, although no other source mentions the elaborate legend surrounding his battlefield last stand, with most other sources claiming he died in disease while in his capital city. Regardless, after 1310 the city is most effectively viewed as a vassal state of Łocǫ́lhəo.

Taos came to be ruled by T'òyłóna, who was married to Cínemąxína's eldest child, Píanakwíame. Despite later customs, particularly those influenced by European traditions, viewing this shift patrilineally as a change of dynasty, in Cínemąxína's lifetime his people likely would have been organized into matrilineal clans, with descent matrilineally being more important. As such, T'òyłóna would have been the most logical heir to Cínemąxína, but his legacy is marred by his vassalage to a foreign chief, and by the later events that transpired in the kingdom. According to the Tǫ̂mąłácianą, a recount of the Tǫ̂mą War of the 1340s, which was written at least two centuries after Cínemąxína's death, Cínemąxína's heir would have been his second child Cíło'ȕ. This is attributed to a cultural shift in the region, especially after European contact, in which heritage was viewed more patrilineally. Additionally, in the context of the Tǫ̂mą War (literally “Father War”), Cíło'ȕ's designation is seen in order to form the reasoning of the later conflict. Despite these later claims to explain why T'òyłóna’s line was usurped, this would not have been viewed as factual at the time of his ascension.

Early Hų́łothə́na Wars

The past few decades in the region saw the beginning of early, formative wars in the history of the Puebloans, but the first major war would not formally emerge until around 1320, with the beginning of the Hų́łothə́na Wars. The conflict would consist of a decades long struggle between the Puebloans and the Hohokam, as well as various other nations, that would not reach a high point until the later half of the century. By the beginning of the conflict, the Puebloans had effectively colonized across a vast region, spurred on by the initial disastrous great drought and its migratory effects. The northern stretch of the Paslápaane (Rio Grande) had come under the sway of the city of Taos, while south of Ohkay Owingeh a series of dozens of settlements emerged, with settlers from Chaco and Łocǫ́lhəo primarily. Influential cities south of Ohkay Owingeh would include Cǫ́lʼoma, Kotyit, and Nafiat, but known so important as the city of Thǫ́ne (Albuquerque), which was definitively settled by 1315.

West of the three cities of Taos, Chaco, and Łocǫ́lhəo, and their various domains, resided various other Puebloan city states, such as Oraibi and Talastima, with their territory stretching west past the ʼHakhwata River (Colorado). In the southwest this rapid migration had led to conflict with numerous other cultures that already resided in the path of the Puebloans. The territory of the Puebloans roughly terminated south of the city of Wupatki, where it met the border of the North Sinagua, who ruled settlements such as Pasiwvi and Wupatupqa. Southwest of them resided the South , who controlled ‘Haktlakva and the infamous fortress of Kánałó. The largest nation southwest of the Puebloans would be the Hohokam, who stretched as far north as the Paayu (Little Colorado River) in the north to the great city of Siwañ Wa'a Ki in the south.

A complex series of fortresses began to be constructed by local powers, in an effort to deter migrations and raids, which became known as the hų́łothə́na. At their largest, these structures would become immense cities of their own, built into cliffs and canyons, and becoming the nexus of local feudal empires. The first known hų́łothə́na to emerge is Kánałó, built around 1300, but by 1320 the number of such fortifications increased dramatically, changing greatly in style based on the local resources and terrain available. The hų́łothə́na would primarily be concentrated around the Valley of the Sun, and extending north toward the edges of the Hohokam domain, with the largest concentrations being around fertile regions contested by both parties simultaneously.

Chronicles from Taos mention that in the early 1320s a proxy war emerged in the Middle Land, as the Zuni leadership became increasingly persuaded to align with the northern Puebloans. As the confluence of the Puebloans, Hohokam, and Mogollon, the region was increasingly diverse, with each side managing to attract settlers to take up arms in raids against the others. In the east the settlement of Abó, located south of Thǫ́ne, came to mark the southeast edge the Puebloans’ colonization, while in the southwest they became halted at the Paayu. After several initial years of light fighting, the Hohokam secured the river with the founding of the Petrified House, which became an infamous hų́łothə́na in the north. According to the Puebloans, it was there that the Hohokam took victims to be tortured and eaten, and it became a dark fortress marking the end of friendly territory.

About two years later, in 1325, the Puebloans countered with the founding of Homolovi, a fort that later developed into a non-fortified town, located due west of the Petrified House, on the southern bank of the Paayu. During this initial phase of the war, in which battles were fewer and in smaller scale compared to the later events of the war, the stretch of river between these fortresses would become a constant sight for skirmishes and raids. The Petrified House remained in operation, with close support from the nearby Hohokam town of Tjukşp 'o to the south, while also trading with Mogollon towns to the southeast, which were largely connected to the site by river. Meanwhile, the Puebloans relied on supply from Wupatki, which was far less secure, due to the river being often times captured by the Sinagua nations.

Tǫ̂mą War

Formation

The Tǫ̂mą War effectively united Taos under the sway of Chaco, bringing together much of the Puebloan world under one city, and this was further expanded in 1360, through a union with Łocǫ́lhəo. The union is believed to have been motivated by the rapid mobilization of the Hohokam people in the south, who brought upon renewed hostility against the Puebloans.

Late Hų́łothə́na Wars

The Puebloans had initially been successful in the intermittent skirmishes with the Hohokam and others, as they pushed further south and founded new colonies. Despite the high cost of supporting settlements such as Homolovi, which sat in the vicinity of Hohokam settlements and hų́łothə́na, the Hohokam were initially unable to fully dislodge the Puebloan settlers of the Paayu. In 1340 a Puebloan contingent marched south from the town and successfully sacked the city of Tjukşp 'o, which shocked the southern nations of the region. Fearing the combined strength of the Puebloans should they invade formally, especially with the Tǫ̂mą War ongoing and seemingly concluding in favor of further unification, the Hohokam were motivated to centralize as well, and prepare to strike back against the invaders.

The O'odham nation was born under the leadership of Kovnal (Chief) Hidoḑmakai, who ruled from the city of Siwañ Wa'a Ki, and a religious figure known as Hidoḑpionag, meaning “The Burnt Priest”. He immediately struck back against the Puebloans, retaking Tjukşp 'o, consolidating the Petrified House, and sacking Homolovi. Hidoḑmakai’s initial war was short lasting, as he did not pursue the Pueblians much farther, after expelling them from the Paayu. He would fight numerous battles in the Middle Lands as well, where raider companies made their mark in the service of either side, despite the Zuni of Shiwinna eventually becoming formally neutral in the conflict.

After warfare continued to ramp up in the late 1350s, the Łocǫ́lhəo Union and the creation of the Póyuopǫ̏'óne (“Three Nations”) formally began another major phase in the Hų́łothə́na Wars. This newfound union would be tested in 1360, when it launched a full scale invasion into the Valley of the Sun. The Puebloan army would come to the outskirts of Siwañ Wa'a Ki, near the confluence of the Keli Akimel (Gila River) and the Onk Akimel (Salt River). The Puebloan leader, Cǫ́ltòbúna, ordered the construction of a hų́łothə́na, which would one day become the great city of Cíwena (Phoenix), in order to strike at the capital city in due time. His vision would not come to fruition, as the Puebloans were defeated in a major battle between the two encampments, which pushed the Puebloans away from the city for the time being. For the next five years the Puebloans or their allies continued to hold Cíwena, although with heavy losses. The O’odham would build another notable hų́łothə́na north of Cíwena at Celşaḑmi:sa, which further put pressure on the Puebloans.

Cíwena’s government would often flip allegiances, depending on which local chieftain manages to seize control during a Puebloan withdraw. As a result, initially the city was not formally destroyed by the O’odham. This would change in 1366, when Hidoḑmakai launched an attack against the city proper, known as the First Battle of Cíwena. The attack failed, and the fledgeling settlement pledged allegiance to Póyuopǫ̏'óne. The following year the O’odham formed an alliance with the Sinagua, who attacked north to great success against local Puebloan colonies. In 1369 Hidoḑmakai marched north to join his allies, successfully razing the city of Wupatki and traveling up the Paayu. This forced the creation of a Póyuopǫ̏'óne-Cíwena-Hopi alliance to counter his invasion.

The O’odham under Hidoḑmakai advanced as far north as the ‘Hakhwata (Colorado River), inflicting heavy damage to the various cities in his wake. At the city of Ongtupqa (Grand Canyon), he was met by a coalition army under the command of the newly christened Chief of Łùłi'heothə́na (Canyon of the Ancients), which had been recolonized by Łocǫ́lhəo. The resulting battle ended with Hidoḑmakai’s death, breaking the momentum of the northern invasion. He was succeeded by Ciojmaḑgakoḑk, whose ascension was followed by a Puebloan recapturing of the Paayu and the lands up to Cíwena in the following years.

Póyuopǫ̏'óne would form an alliance with the Mogollon, in which they settled their earlier disputes, and the Puebloans ceded most of the border territory seized from the Hohokam to them. As a result the mid 1370s saw the Puebloans and Mogollon seizing northeast O’odham. In the north the Puebloans would achieve victory at Wupatupqa in 1376, but fail to capture Kánałó, while in the south the Second Battle of Cíwena would likewise result in a narrow Póyuopǫ̏'óne victory. Around this time the North Sinagua came to be ruled by Puuhutaaqa, who made peace with the Puebloans, with the South Sinagua then overrun. In 1377 the Sinagua city of Honanki was captured, as was Celşaḑmi:sa after a brief siege.

The following spring Ciojmaḑgakoḑk died near Mogollon lands, leaving a young son named Baikam as ruler. Under the leadership of the regent Hevacuḑ, a ceasefire began known as Hevacuḑ’s Peace. The Puebloans managed to hold onto Cíwena, and now resumed heavy settlement of the region, while the Hohokam looked south toward the coast, settling colonies further outside the reach of the northerners. It was during this time that the great city of Shuhthagi Ki:him would be founded, which would one day become one of the dominant states of the region, as Xacapáy, or the Kingdom of the Delta. Additionally, after the death of Puuhutaaqa, a son born of the Sinagua and the Hopi, Tuukwiʼomaw would unite the region south of the ʼHakhwata, which formed the Yavapai Confederacy. By 1386 the Yavapai had absorbed the last of the Sinagua nations.

In 1387 the peace between the Puebloans and the O’odham finally broke down, beginning the Two Rivers Campaign around Cíwena. The Battle of Keli would solidify Puebloan control over Cíwena, and in 1389 the city of Siwañ Wa'a Ki was besieged. With the city’s fall, the old Hohokam empire ceased to exist, and the Hų́łothə́na Wars finally came to a close. Siwañ Wa'a Ki would not be rebuilt to its former glory for many years to come, allowing Cíwena , and its Puebloan king, to replace it as the dominant power of the south. Baikam of the O’odham would manage to escape the sacking and retreat to the city of Cemamagĭ Doʼag further south, but he never managed to return to his fallen capital. Instead the O’odham trend southward continued, with the nation’s people settling along the far southern coast, or in nearby city states such as Shuhthagi Ki:him.

Government

The exact nature of the governmental forces in the early Three Nations is a point of contention for many modern historians. It is likely that any central authority ruled by indirect means, through a system of tributes rather than a single unitary form of government. This is exemplified on the local level by the fact that the major cities of the early Three Nations functioned as microcosms for the empire as a whole, with cities being comprised of up to several dozen small, fairly autonomous villages within the same area. This is especially clear in the city of Chaco, where historians know of multiple chiefs coexisting up to the fourteenth century. It is believed that the districts of the future city initially functioned quasi-independently, and it is theorized that the social upheaval of the time may have contributed to unifying these communities into single cities.

For much of its early history the Three Nations’ empire would have consisted of a patchwork of mostly autonomous towns and villages, and it is unclear to what extent the central government claimed authority over them. Many of the empire’s settlements remained disconnected from the major cities, either due to discontinuous territory, or due to their distance from any early infrastructure. Generally none of the major three cities interfered with local, culturally-similar towns that they acquired, as long as tribute was paid in some form. The same can be said for settlements founded by the Three Nations’ citizens, which functioned in a similar way to a colony in most locations.

The nature of the titular three polities and their relationship to each other is also debated. Around the year 1310 the city of Taos was effectively vassalized by Łocǫ́lhəo, but the city of Taos continued to have minimal interaction with Łocǫ́lhəo’s government. It is believed that the founding of the Three Nations was a mutually agreed upon alliance due to external pressure, but it is unclear to what extent a city such as Taos was able to contest it. From about 1360 onward the empire operated under the governance of a “high king”, usually from Łocǫ́lhəo, but minor chiefs in other cities continue to exist.

The Ancestral Puebloan culture as a whole undoubtedly extended far beyond the borders of the Three Nations, although some cities blurred the line between territory and neighbor. The land of Halona Idiwan’a (Middle Place), centered at the city of Shiwinna, was settled at a similar time to the city of Taos, and existed roughly in the middle of the Ancestral Puebloan world. It is unclear exactly when the middle territory was incorporated fully into the empire, if at all, however, it is clear that the city of Shiwinna contributed to the empire’s military endeavours closely.

Cities such as Talastima and Oraibi, which inhabit the region west of the primary Three Nations, are generally considered to be independent of the empire, however, historians argue that this is untrue or at best misleading, as these cities contributed throughout the Hų́łothə́na Wars alongside the armies from the three cities. The same is true for the cities south of the Three Nations, such as Thǫ́ne, which were likely independently settled by Ancestral Puebloans for the most part, but eventually accepted the protection of the Three Nations. Nevertheless it is clear at this time that Cíwena was solely independent of the Three Nations despite being a similarly Ancestral Puebloan settlement.

Language

Despite being linked closely by similar cultural and religious practices, the people of the Pueblo region spoke vastly different languages, estimated to be descended from at least four different language families. This would partially be a consequence of the many migrations of the Puebloans, as well as interactions with many different neighboring cultures. Different language families of the region possessed different vocabulary, grammar, and other linguistic aspects, resulting in neighboring regions speaking mutually unintelligible languages. After the rise of the first unified nations in the Puebloan region, a sole language would be selected as a lingua franca.

Language Families of the Pueblo Region:

- Keresian: Language family believed to be derived from the Łocǫ́lhəo region, which spread southeast to the towns of the Paslápaane Region during the Great Drought.

- Zuni: A language isolate spoken only by the Zuni people.

- Kiowa–Tanoan: Language family of the northern Paslápaane Region and the P'aeyok'ona Region, from which the Taos language derives.

- Tewa: Originally the most widespread Tanoan language group, with speakers across the Paslápaane region and north to Ohkay Owingeh.

- Tiwa: The language family of the northern Paslápaane and Taos. Often split into north and south dialects, with the northern speakers being native to Taos, and the southern speakers be present in their colonies in the far south.

- Towa: Solely spoken by the Walatowa people, located southwest of Taos.

- Kiowa: Language of the Kiowa People, who would later settle the great plains of the continent. The language likely split from the Puebloans around the year 1300, as settlers traveled north from the Taos region, and later into the plains.

- Uto-Aztecan: Widespread language family, from the Nahuan languages (also known as Aztecan) of Mexico to members of the Puebloans in the north. Through early contact or migration, Aztecan practices spread to the Puebloan region by 2100 BCE, while later languages would derive from, or spread from, the languages of the Aztec civilization and its neighbors.

- Hopi: A language formed from the Uto-Aztecans of the south and the Ancestral Puebloans of the north and east.

- Piman Languages:

- Oʼodham Languages:

Tohono Oʼodham (Desert People) Akimel Oʼodham (River People) Hia C-ed Oʼodham (Sand Dune People)

- O'ob No'ok - Minor language of the Chihuahua-Sonora Region.

- O'otham/Tepehuán - Language of the Chihuahua-Durango Region.

- Nahuan Languages: Trade between the Aztecs, and other Nahuan peoples of the south, would result in direct forms of Nahuatl being spoken.

- Mexicanero: A language spoken on the periphery of the Mesoamerican world, near the southernmost region of the Mogollon culture (OTL Durango).

- Yuman–Cochimí Languages:

- Delta–California Yuman

- Cochimí (Central Baja)

- Kiliwa (North Baja)

- Plains Sign Language: Widely used visual trade language, used as a lingua franca across the Great Plains and neighboring areas.

List of Rulers

Rulers of Taos

- Cínemąxína

- T'òyłóna (c. 1310 - c. 1330)

- Sə́onxę̀m (c. 1330 - c. 1340)

- Cínemąxína II (c. 1340)

- Łúnaę́nemą (- c. 1360)

- Cǫ́ltòbúna (c. 1360 - c. 1390)

- Wǫ́nemąxína

Rulers of Chaco

- ’’No central leader’’ (c. 1290 - c. 1320)

- Hȕthócûdena

- Pìwxòyłúona

- Muuyawmoʼa

- Tòpháy’ȕ

- Muuyawmoʼa (c. 1320 - c. 1330) (As High Chief)

- Sə́onłacina (c. 1330 - 1340)

- Muuyawmoʼa (c. 1340 - c. 1345) (Restored)

- Pę̀łúona (c. 1340s)

- Tòpháy’ȕ II (c. 1340s)

- C’ùlną́nemą (c. 1340s - c. 1360)``

Rulers of Łocǫ́lhəo

- Łàcic’élena ( - c. 1320)

- Tą̀tə̀’ə́wyu (c. 1320 - 1340)

- Cǫ́ltòbúna (c. 1340 - c. 1390)

- Cìacǫ́lsə́on (c. 1390)

- Phàymųyò’óna

Primary Sources

- Łácianątə̂otho - Written c. 1400. Details the history of Taos, life of Cínemąxína, and the reigns of his successors up to the reign of Cǫ́ltòbúna.

- Tǫ̂mąłácianą - Written c. 1520. Details the history of the Tǫ̂mą War and surrounding era (c. 1335 - 1355).

- Hų́łothə́na Pìwcìayána - Written c. 1500. Details the Hų́łothə́na Wars (c. 1320 - 1390).