Mexican Civil War

| Mexican Civil War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

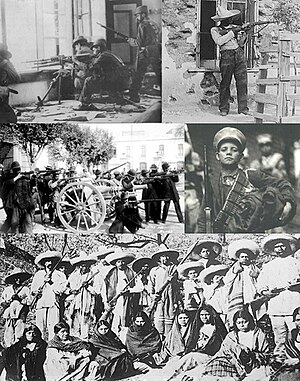

Collage of the Mexican Civil War | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

1910–1911: Federal Army led by Porfirio Díaz |

1910–1911: Maderistas Orozquistas Magonistas Zapatistas | ||||||

|

1911–1913: Maderistas |

1911–1913: Forces led by Bernardo Reyes Forces led by the general Mareo Velasques Félix Díaz Orozquistas Magonistas Zapatistas | ||||||

|

1913–1914: Forces led by Victoriano Huerta |

1913–1914: Carrancistas Villistas Zapatistas | ||||||

|

1914–1919: Villistas Zapatistas Forces led by Félix Díaz Forces led by Aureliano Blanquet |

1914–1919: Carrancistas | ||||||

|

1920: |

1920: | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

1910–1911: 1920: Álvaro Obregón |

1910–1911: Pancho Villa Venustiano Carranza Victoriano Huerta Aureliano Blanquet 1913–1914: Venustiano Carranza Pancho Villa Emiliano Zapata Álvaro Obregón Plutarco Elías Calles 1914–1919: Venustiano Carranza Álvaro Obregón 1920: Venustiano Carranza † | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

250,000 – 300,000 |

255,000 – 290,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

|

700,000 to 1,117,000 civilian dead (using 2.7 million figure) | |||||||

The Mexican Civil War (Spanish: Guerra Civil Mexicana), also known as the Mexican Revolution (Spanish: Revolución Mexicana), was a period of major political and social upheaval between 1910 and 1925 that included armed conflict, numerous regime changes, and foreign intervention. Its initial outbreak resulted from the failure of the 31-year-long regime of Porfiro Díaz to resolve various succession disputes. A political crisis emerged after wealthy landowner Francisco I. Madero challenged the results of the 1910 presidential election and revolted under the Plan of San Luis Potosí. Armed conflict began in the North and Díaz resigned in exile to France following the signage of the Treaty of Ciudad Juárez and establishing a republican government.

Following the interim presidency of Francisco León de la Barra, Madero was elected as president in new, fairly held elections. Madero lost favor from both the conservatives and the revolutionaries, and he, along with his vice president, Pinó Suarez were deposed and assassinated in February 1913 during the Ten Tragic Days (Spanish: La Decena Trágica). The counter-revolutionary regime of General Victoriano Huerta came into power with the backing of the Sierran government, along with supporters of the old order and local business interests. Huerta's rule was highly controversial and his refusal to work with the revolutionaries plunged the country into the first civil war of the Revolution between 1914 and 1915. The Constitutionalist faction under wealthy landowner Venustiano Carranza prevailed by 1915 and defeated the revolutionary leaders Pancho Villa and Emiliano Zapata.

In 1916, Pancho Villa attacked the Sierran border town of Columbus, West New Mexico, prompting Sierra to lead a limited military expedition into Mexico to capture Pancho Villa, known as the Punitive Expedition. The Constitutionalists, who were initially friendly with the Sierran government, were opposed to Sierran military presence in Mexico and sought to repel them out. In the Battle of Carrizal, the Sierran expeditionary forces suffered huge losses at the hands of the Mexican Army. Following a retaliatory Sierran attack in Chihuahua City, Mexico declared war on Sierra and Sierra intervened by launching a large-scale invasion against the country. Brazoria entered the war on the side of Sierra as well upon the execution of a secret military alliance the two states signed in 1910. The pretext of the intervention by the Anglo-American powers was to restore order to Mexico under a stable regime and to capture Pancho Villa. The Constitutionalists split between the Carrancistas, who opposed the military intervention, and the Obregónists, whom the Sierran government supported to lead the country, through previously arranged contacts and security guarantees. Obregón became the president and the Treaty of Veracruz in 1917 was signed, whereby Brazoria and Sierra would recognize Obregón's regime and oversaw the development and promulgation of the 1917 Constitution.

The Anglo-American intervention was immensely unpopular among the Mexican public and Obregón was viewed as a traitor to the Revolution by various factions and revolutionary leaders, including the Villistas in the North and the Zapatistas in the South. Sustained guerrilla warfare and insurgencies throughout the country continued to plague Obregón's government. In 1919, the United Commonwealth, which had fallen under the Continentalists, began to back the leftist insurgencies in the North and the South. The entry of the United Commonwealth as an involved power emboldened the revolutionaries opposed to Obregón, leading to a second civil war. Although the North was militarily defeated, a war of attrition lasted for two years in Southern Mexico, centered around the state of Oaxaca. The Armistice of Mascagni resulted in the cessation of hostilities and marked the official end of the Revolution with the division of a Constitutionalist North Mexico and a Continentalist South Mexico, as well as an independent Yucatán.

Prelude

In the 1860s admist the backdrop of the American Civil War, France launched a military invasion of Mexico initially under the guise of seeking to acquire debt that Mexico had acquired from loans it took from France and several other European countries during the Reform War of years before, but was in reality an attempt to re-establish a French overseas colonial empire. Ordered by Napoleon III, France would invade Mexico and establish the Second Mexican Empire with Austrian-born noblemen Maximilian Habsburg-Lothringen taking over as Emperor of Mexico. During his reign, Maximilian I would modernize Mexico and help rebuild the nation after the war and oversaw the industrialization of the country, increased foreign investment, and general improvement of its major cities through urbanization. He also oversaw friendly relations with most of the international community, especially with the various European states such as France, Austria, Spain, Germany, the United Kingdom and several others. While great gains were made, Mexico was dependent on France for economic and military protection and security. This made Mexico a de-facto protectorate of France and was one in which major influence was exerted upon the country even after Napoleon III was removed from power after the humiliating French defeat in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–1871.

Maximilian I would tie Mexico's improvement, position in the world, and success to that of its alliance with France and its connections to Europe at the cost of economic sovereignty and allowing foreign influence and interference in Mexico's internal affairs. Towards the end of his reign, Maximilian would resort to contentious methods to hold onto power including using any means to suppress the underground republican movement in Mexico that was a threat to his reign. Landonism, a form of communist ideology inspired by the interpretations of Karl Marx and his philosophy by Sierran philosopher and revolutionary Isaiah Landon, would grow among Mexico's republicans who saw Landon's revolutionary ideology and anti-monarchist sentiment as appealing to their gripes with the Mexican monarchy, especially due to its foreign origins and deep routes in French imperialism, a concept that Landon denounced along with all other forms of European imperialism and colonialism.

Failed regency attempt

Shortly after Maximilian died, several members of the royal family and federal government attempted to establish a regency council to allow for a proper successor to the position as emperor. The late emperor's son, Maximilian II, was too young to govern the country and so the Imperial Regency Council was established a day after Maximilian's death in 1910 with the intent to ensure stable governance and allow for a smooth transition of Maximilian II to the position as emperor, however these efforts would be thwarted by internal unrest, infighting, corruption and a general lack of popular support from much of the Mexican public.

Towards the end of Maximilian I's reign and life, Mexican Army general Porfirio Diaz had become the de-facto leader of Mexico and carried out the day-to-day governance of the Mexican Empire per the request and conest of Maximilian I himself. After the emperor's death, Diaz took over as acting leader of the Mexican Empire and as the effective regent of Mexico until a formal regent had been selected to lead the empire until Maximilian II came of age, however infighting persisted and many believed that Diaz was attempting a power grab and was willing to use the Federal Army as a tool to become Mexico's next ruler.

Course of the revolution

End of Porfiriato

Interim Presidency

Madero Presidency

Ten Tragic Days

Huerta Presidency and first civil war

Carranza Presidency

Punitive Expedition

Anglo-American intervention and second civil war

Treaty of Veracruz

Entry of the United Commonwealth

War of attrition in the South

Armistice of Mascagni

Aftermath

Legacy

See also

- Start-class articles

- Altverse II

- Mexican Civil War

- History of Mexico

- Modern Mexico

- Wars involving Brazoria

- Wars involving Mexico

- Wars involving the Kingdom of Sierra

- Wars involving the United Commonwealth

- Landonist revolutions

- 20th-century revolutions

- Military history of Mexico

- Civil wars involving the states and peoples of North America

- Wars involving Germany

- Wars involving the United Kingdom

- Proxy wars

- 20th century in Mexico