Shehari War

| Invasion of Tihama | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

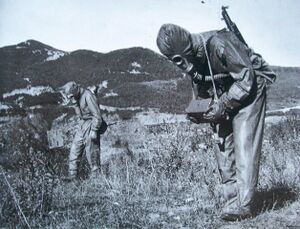

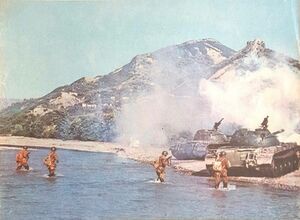

Clockwise from Top Left: Rubble after a Mezrehi bombing of Borsat in 1994. Tihaman artillery battery fires on Mezrehi positions, Mezrehi infantry under fire, Tihaman soldiers undergoing a Mezrehi artillery barrage, Mezrehi soldiers during a patrol, 2002. Tihaman soldiers surrendering after the encirclement of Al'Kasrah,April 1993. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Logistics support:

|

Logistics support:

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

Total military casualties: Breakdown

|

Total military casualties: Breakdown

| ||||||

The Shehari War, also referred to as the Great Patriotic Resistance in Tihama, was a protracted armed conflict fought primarily between the Socialist Federal People’s Republic of Tihama and the Shehari Republic of Al’ Mezreh from April 17th, 1993 to January 12th, 2004, with a prolonged ceasefire from 1996-2000. The war officially came to an end with the Mezrehi capitaulation of January 12th, 2004. The conflict was initiated after a surprise invasion of Tihama by the armed forces of Al’ Mezreh, which, at least at first, made substantial territorial gains due to the element of surprise, a sluggish Tihaman response in some sections of the front, and initial local numerical superiority.

The official casus belli cited by the government of Al’ Mezreh was to stop Tihaman aid and support to rebel separatist groups along the border of the two nations. Indeed, Tihama had been arming and training rebel groups aiming to establish an independent state between the two countries for years prior to the war, and Mezrehi forces had been deployed across the region in an attempt to quell instability. However, the Mezrehi Government could not provide any evidence to support their claims upon the start of the invasion, and as a result were met with substantial international condemnation and sanctions.

The war was exceptionally intense, especially in the first few years of fighting, seeing both massed conventional warfare between armored and mechanized forces in the northeast, as well as grueling static warfare and asymmetrical guerilla operations by both sides across the wider front. It was the largest clash of armies on the continent of Colytheus since the Second World War, and featured many “firsts” for both sides. Both sides accused each other of war crimes and violence against civilians, and both sides violated international arms limitation treaties during the war. Tihaman ground and air forces deployed chemical weapons on a large scale during combat operations, including mustard gas, tear gas, and sarin nerve gas, while Mezrehi forces used flamethrowers in urban civilian environments, and Mezrehi security forces deployed wooden bullets against civilians in their own territory during counter-insurgency operations. The conduct of the conflict has been widely characterized as archaic and outdated, often featuring Mezrehi forces mounting human wave-style assaults against hardened Tihaman positions featuring minefields, trenches, barbed wire, heavy artillery, and machine gun nests, not to mention the aforementioned use of flamethrowers and chemical weapons.

Opposing forces

Tihaman People’s Army:

At the start of the conflict, the Tihaman People’s Army, across all branches of service, was one of the world’s largest militaries. Though roughly half the size of its present-day iteration which has swollen to an enormous size as a result of the tension caused by this war, it still numbered over half a million men. The Tihaman armed forces possessed the largest collection of armor and artillery on the continent (though most of it was somewhat dated), and the military had been on a heightened state of alert in light of recent troop movements detected near the border. In addition, the army could mobilize another half a million reservists within a few days of the outset of hostilities, which high command presumed would allow it to dwarf its adversary. The Ground Forces possessed over 4,000 tanks and 2,000 APCs/IFVs at the start of the war, a number that has only grown since the ceasefire, as well as nearly 10,000 self-propelled and towed artillery pieces and rocket systems. In addition, the Ground Forces and Strategic Rocket Forces operated over 2 dozen ballistic missiles within range of the front lines and capable of striking targets well within enemy territory. Tihaman motorized, armored, and mechanized units were supplied with ample numbers of artillery pieces, air-defense equipment, and anti-tank artillery and guided missiles. Reserve divisions and brigades were somewhat less equipped, mainly featuring older equipment, but were still capable of manning static defensive lines. In addition to the half a million active army troops, the Border Guard Corps had another 45,000 men already stationed across the frontier, and the Red Guards paramilitary force could mobilize a further 600,000 reservists within a week of hostilities.

The nation also possessed a dense air-defense and static ground defense network. In particular around the capital of Nitra, Tihaman permanent SAM sites were established. Roughly 5,000 SAM systems and anti-aircraft artillery pieces were at the army’s disposal at the outset of hostilities, as well as over 10,000 MANPADs. Across the frontier existed hardened border checkpoints, largely manned by the lightly-equipped Border Guards Corps, but it was assumed these would at least temporarily hold up an enemy attack long enough to organize a counterattack.

In the air, the Tihaman People’s Army Air Force was fairly evenly matched with its opponent. Of its 1,200 fighter aircraft, only about ⅓ were combat-ready when fighting broke out, and at least half its inventory required maintenance to be combat capable. Nevertheless, within 2 weeks of war the Air Force had the bulk of its aircraft in the sky and even mounted raids against enemy towns across the border (paying attention not to bomb Irashani targets.) During the early phase of the war, it was found that Tihaman pilot’s consistently performed poorly compared to their adversaries. As a result, an international training mission from Tihaman-aligned countries including the UFRR, Baclia, and Daehan supplied technical and combat support for Tihaman airmen, and eventually the combat performance and availability of Tihaman pilots and aircraft drastically increased. The Army possessed over 200 attack helicopters and the Air Force fielded roughly 450 dedicated ground-strike aircraft at the outset of war, both of which performed well in hunting and destroying Mezrehi armored columns.

At sea, the Tihaman People’s Army Navy dwarfed its opponent. Tihama enjoyed a nearly 3:1 advantage in numbers of ships, and while Al’ Mezreh had been investing in its navy in recent years, the Tihamans had very clearly out-spent them. The Navy had one aircraft carrier in service and another building, both of which could operate aircraft for power-projection missions. Additionally, the fleet had recently been experimenting with amphibious warfare tactics, and could land entire battalions of naval infantry supported by armored vehicles. Also present in the fleet were a pair of large guided missile cruisers, 8 destroyers, and over a dozen frigates and corvettes each, all capable of land-attack missions. Below the surface, the Tihaman submarine fleet operated largely unchallenged by the enemy, and Tihaman submarines immediately launched anti-commerce and fleet strike missions in the first week of hostilities. The submarine fleet would be expanded even further during the war, as the nation’s high command continually looked upon it as a tool with which to strangle the enemy’s commerce and ability to wage war.

Armed Forces of the Republic of Al’ Mezreh:

On the eve of the war, the Mezrehi Army (ground force) numbered roughly 450,000 men. Despite its smaller size when compared to its intended adversary, the Mezrehi Army was generally in high spirits and hinging on surprise to attain victory. Overall doctrine stressed utilizing the army as a weapon of infiltration, negating superior Tihaman firepower and technology by spreading its forces evenly across the front, utilizing its superior on-foot mobility to cover rough terrain which the more mechanized Tihaman forces could not fight effectively in. Support for the infantry was to come from a great number of conventional artillery pieces, the majority of which were outdated, but nevertheless capable of substantial firepower.

This “infiltration-style” warfare was to be further reinforced by some 85,000 “Holy Martyrs”, lightly-equipped but fanatical units deploying tactics like suicide bombings and car bombs in order to cause chaos and confusion at Tihaman border checkpoints, softening them up for the main invasion force. These troops often appeared in civilian clothing during the first day of the invasion, ambushing Tihaman border forces and wreaking havoc, after which they would move into the nation’s interior and function as guerilla fighters and intelligence-gatherers to notify the regular army of enemy movements.

The Mezrehi armored forces were dwarfed by their adversaries, possessing only about ¼ of the armored vehicles of their opponents. However, Mezrehi infantry units were widely supplied with shoulder-launched anti-tank rockets, improvised explosives, and demolition charges for use against Tihaman armor. A great number of portable mortars were also issued for mobile fire-support, as the army’s critical shortage of prime mover vehicles would make it difficult for the artillery to follow behind the invasion force. Further support for the invasion force would come from the army’s riverine flotilla of heavily-armed patrol boats, transferred from the navy and equipped for riverine warfare with additional armor plating, machine-guns, and grenade launchers of various types. These vessels would see extensive use in the coming campaign.

In the air, the Mezrehi Air Force was once again dwarfed by its opponent. The Mezrehis possessed only about 450 frontline fighter aircraft compared to the 1,200 fielded by Tihama. However nearly the entire Air Force was serviceable on the day of the invasion compared to only about ⅓ of the Tihaman Air Force, leaving the two adversaries roughly evenly-matched. Mezrehi pilots consistently performed better than their opponents during the first few months of the war, inflicting a nearly 2:1 casualty ratio before their numbers started dropping from losses to Tihaman anti-aircraft weapons, operational attrition, and the increasing size of the Tihaman People’s Air Force. The country did, however, possess a large anti-aircraft network, which was continually being bolstered through purchases of new systems from overseas. All told, 5,000 anti-aircraft guns and 3,500 SAMs of all types were fielded, about ⅓ of which were of the current generation. Army units were also issued with 3,750 MANPADS purchased on the black market during the years leading up to the war. However, as the war went on and international sanctions continued to mount, parts and replacements for these advanced missiles became harder to obtain, and the Mezrehis were forced to continually rely on conventional anti-aircraft guns to turn away attacks from Tihaman bombers. An area where the Mezrehi Air Force excelled however, was in the operation of turboprop-powered aircraft. Local industries and foreign suppliers had furnished the Air Force with no less than 500 turboprop-powered aircraft, largely intended for reconnaissance and light ground strike missions. Initially, these aircraft proved successful, as they could fly low and slow enough to avoid the big Tihaman state-of-the-art SAM batteries, however they eventually began to fall victim to the increasingly large number of MANDPADS and conventional anti-aircraft guns issued to Tihaman ground units, and were eventually restricted to night-time operations only during the last years of the war, where targeting them was more difficult.

At sea, the disparity between the two nation’s militaries was most apparent. The Mezrehi navy was largely a brown-water fleet, possessing limited capabilities for offshore operations. Its core was composed of 14 destroyers of Second World War-vintage, though substantially modernized during recent naval modernization programs with modern anti-ship missiles, anti-submarine equipment, and electronics. The navy relied heavily on light, affordable patrol vessels and missile boats, the majority of which are of limited range and capable only of coastal operations. However, due to their great numbers, they were a potent deterrent against enemy naval invasion, due to Tihaman captain’s fears of being overwhelmed by the sheer numbers of the enemy “mosquito fleet”, as it came to be called by both Tihaman commanders and foreign observers. The Mezrehi fleet did not possess carriers or a submarine force, but did maintain a large network of coast-defense artillery and missile positions much like it's Tihaman adversaries.

Preparations for war

Initial preparations for war began on the Mezrehi side starting in late 1992. In December of that year, the Mezrehi Armed Forces began massing large concentrations of troops along the Tihaman border, the majority of which were moved to the northeast, the flattest and most developed area of the border between the two nations. As a result, the bulk of Mezrehi armor was to be deployed to assist the thrust along this axis. Despite continual Tihaman monitoring of the border by both ground and air-based reconnaissance units, the buildup went largely unnoticed. Mezrehi commanders were keen to conceal their actions, troops were briefed in underground shelters or warehouses instead of out in the open, tanks were concealed in hardened storage compounds or underground storage areas, artillery emplacements were covered in foliage and camouflage netting, and hastily-prepared airfields near the front were covered in artificial vegetation. As a result, Tihaman generals tended to ignore reports of Mezrehi troop movements, believing there was not a sufficient concentration of troops to constitute a threat.

The invasion plan was quite simple, the bulk of Mezrehi forces were to be concentrated into two army groups: Army Group Red, assigned to the Northeastern front, numbering some 290,000 men plus another 20,000 volunteers in 2 divisions from the Shehari Republic of Yehosa, and Army Group Yellow, numbering around 105,000 men and assigned to the Eastern front. The Central/Southern Front would be attacked by the “Holy Martyrs”, assigned collectively to the Mezrehi “National Liberation Front”, a fundamentalist religious militant organization reporting directly to the President of Al’ Mezreh. These asymmetrical forces numbered some 85,000 men. This put the invasion force at nearly half a million men across the whole front. The invasion was planned to coincide with a huge Tihaman military parade in the capital city of Nitra, celebrating the anniversary of the defeat of the 1964 coup d’etat attempt, for which the army’s best units were to be present. As a result, of the 16 Tihaman divisions normally stationed in the northeastern command sector, only about half were at full strength, and the elite Presidential Guards units had all been moved to the capital for parade and security duties.

This left the Tihaman northeastern forces with a manpower strength of around 150-200,000 men facing almost 300,000 Mezrehis, and without their best armored and mechanized units. Across the Southern and Eastern fronts, the situation was also poor for Tihama. The southern border was lightly defended, as Tihaman commanders were convinced the rough terrain would prevent a meaningful thrust along that axis. As a result, only about 24,500 Tihaman Border Guards and low-strength army units were in the vicinity of the southern frontier, totally unprepared for conflict especially against a fanatically motivated enemy using unconventional tactics. In the East, Tihama benefited from strong defensive positions, but the army’s units here were the most understrength. Of all 12 divisions available to the 4th. and 7th. Corps defending the Eastern axis of advance, only 3 were full-strength.

Mezrehi forces were highly motivated and well-prepared, their plans were in place and had been carefully laid, and their enemy was blissfully unaware of, or at least totally unprepared for, the savagery about to be unleashed upon them. On the evening of April 16th, 1993, Mezrehi commanders received their final orders. Troops moved to designated concealed areas, tanks marshaled in camouflaged assault positions, and artillery emplacements were laden with shells and rockets under the cover of darkness. At dawn the next morning, the “titanic struggle”, as Mezrehi President Shehir Rumei Salheman called it in his declaration of war speech, would begin.

The first phase: 1993-1996

Opening moves

The war began at first light on April 17th, 1993. Mezrehi forces emerged from their concealed and camouflaged positions and began advancing rapidly on the Tihaman border. A brief artillery bombardment (about 30 minutes long) preceded the advance, as hundreds of Mezrehi guns and multiple rocket launchers broke the silence of the night. Mezrehi Army Group Red, under General Abnomahadi Zeh Heda, was to force the Tihaman border, achieve a breakthrough, and advance to the strategically important border town of Haraat, some 10 miles inside the Tihaman border. It was located at the crossroads highways 7 and 12, the two major highways linking the two countries, as well as the site of the command center for the Tihaman northeastern military district. Capturing this center of command and control would deprive 2 whole Tihaman army corps, the 3rd and 9th, of their ability to direct wider combat operations.

Mezrehi forces began their attack on the Tihaman border positions at around 0:530 hours, encountering sporadic Tihaman small arms fire as Border Guards units realized they were under attack. The assault on the hardened border was spearheaded by Mezrehi combat engineers, who broke through using cutting torches, explosive charges, and flamethrowers. The Border Guards units resisted heavily in some pockets, but largely were forced back by the Mezrehis. The gaps in the line were soon exploited by fast-moving armored and motorized formations who encircled masses of Tihaman Border Guard Corps units as they raced across the border. In 3 hours, the Northeastern border had been entirely overrun, over 500 Tihaman troops were killed and another 3,400 taken prisoner. The Mezrehis then attacked the barracks of the 4th Motorized Rifle Division, the army’s closest unit to the border. Caught by surprise and having failed to receive a warning from the Border Guard troops, they were quickly overrun. The barracks was occupied after just 4 hours of fighting, along with large stocks of ammunition, food, and fuel. As daylight dawned, Mezrehi turboprop aircraft took off from improvised airfields across the border, and began bombing and strafing Tihaman troop positions. The Northeastern military district went into a full panic. The regional commander, General Amir Hassan, was in Nitra for the parade, and reportedly was slapped in the face by Supreme Leader al-Hashmi when the news reached the capital.

Hassan was ordered back to the front immediately or face punishment for his failings. Going with him were all 3rd and 9th Army Corps units that were due for parade duties, as well as 2 Presidential Guard Infantry Regiments. Air raid sirens rang out across the Northeastern command district as the longer-range Mezrehi jet aircraft began dropping bombs on civilian and military targets alike in a terror-bombing campaign. Meanwhile, Mezrehi ground forces had surrounded the town of Haraat by lunchtime that afternoon, demanding its surrender. The town was defended by over 10,000 troops of the 7th. Motorized Rifle Division and the 3rd. Cavalry division, who were well-encamped and stocked with supplies. They refused the ultimatum to surrender, vowing to fight to the death. At this point, General Rafsanjani began to divide his forces. Mezrehi 2nd. Corps was to stay behind and move artillery into position to besiege Haraat, while 4th. and 6th Corps. were to proceed with their advance to maintain pressure on the Tihamans. Tihaman Air Force aircraft engaged Mezrehi pilots for the first time around 2:00 PM that day, with a formation of 5 Tihaman fighters turning away an attack on the village of Hafji by 17 Mezrehi turboprop aircraft, shooting down 2 for no friendly losses. Mezrehi fighters arrived shortly after and shot down 3 of the 5 engaging Tihaman aircraft for only 1 loss of their own.

General Hassan, the Tihaman district commander, was panicking. Failure was not an option, and he sat down with his subordinates in the village of Al-Kafna to plan the counterattack. He knew the Mezrehis would attempt to advance to the lakeside city of Borsat, the largest city in the northeastern district, and an important industrial center. To do this, they would have to seize Bridge 112, a state highway bridge over the river Sigrit, about 24 miles south of the city, which would allow them to fan out into the flatter territory approaching Borsat. His first decision, therefore, was to concentrate his forces in the defense of this bridge, bleed the Mezrehi offensive dry, and counterattack to relieve Haraat.

Hassan reorganized his remaining forces into the ad-hoc 12th. Army Corps and ordered them to dig in along the west bank of the river Sigrit, turning tanks into bunkers, emplacing artillery guns, and building machine gun nests. By April 21st, the first Mezrehi shells were falling on this improvised line, the only defense between the advancing enemy and the city of Borsat, 32 miles into Tihaman territory. The Mezrehi 4th. Corps began to force the northernmost edge of the line on the 23rd of April, where the river was most shallow, first attacking in broad daylight and attempting to ford the river with armored vehicles. This approach proved doomed, as the Tihamans were well-encamped, and the Mezrehis lost almost 1,200 men on the first day. That evening, they tried again, sending another 2,000 men to their deaths at the hands of electrical cables slipped into the water by Tihaman forces and massed fire from the defenders. At this point, Hassan made a grave tactical error. He drove his forces across the river in an attempt to force Mezrehi 4th. Corps off the eastern bank of the river and relieve the artillery bombardment of his lines. A hastily thrown-together attacking force consisting of the 8th. Motor Rifle Division, 2nd. Cavalry Brigade, and elements of the 4th. And 9th. Motor Rifle Divisions attacked Mezrehi 4th. Corps on the morning of May 4th, but were overwhelmed by the numerically superior Mezrehis and surrounded by a pincer maneuver as the enemy fell back. Hassan then moved forces from other sectors of the line to try and relieve the besieged units, but they failed to break through. In so doing, the Tihaman commander had left his southern flank greatly unprotected, and Mezrehi 6th. Corps attacked it on the night of May 19th, forcing a breakthrough as squads of sappers with flamethrowers and demolition charges attacked the unorganized and outnumbered Tihamans. By the start of the following month, some 45,000 Mezrehis of 4th. And 6th. Corps had crossed the river and driven the Tihamans back into the city of Borsat. 12,000 Tihamans were killed and another 19,000 captured during the advance, as the 12th. Army Corps collapsed on itself. Hassan avoided almost certain execution when his staff car was hit by a bomb from a Mezrehi turboprop aircraft during the retreat, killing him and 4 of his aides.

1993-1996

On June 7th, 1993, the town of Herat finally fell to Mezrehi 2nd. Corps, following almost 3 months of attritional siege warfare. The Tihamans had lost some 11,000 men killed or captured in the battle, the Mezrehis 6,700. It was a devastating blow to Tihaman morale, and robbed them of their main immediate tactical objective. The goal now was simply to resist the enemy advance. With the fall of Herat and the capture of Bridge 112 over the Sigrit, the city of Borsat was now in the enemy’s crosshairs. Despite an increasingly stiff Tihaman resistance, Mezrehi 4th. And 6th. Corps slowly began the crawl to the city’s southern outskirts, reaching them after almost 3 weeks of fighting on July 3rd. The Tihamans had spent those 3 weeks reinforcing their defenses in the city, stockpiling supplies and evacuating civilians. Over 150,000 people had fled the city or been forcibly removed, and defending this important industrial and command center now fell to the newly-formed Tihaman 10th. Army Corps and its commander, General Rashid al-Hattan. Reinforced with the elite 2nd. Presidential Guards Infantry Regiment as well as with 2 Motor Rifle Divisions, 2 Border Guards Brigades, and 3 Red Guards Militia Brigades, al-Hattan felt confident in his position. He had almost 75,000 men at his disposal, against an attacking force of some 120,000, but he benefited from a strong defensive position and ample supplies. Minefields had been laid across the approach to the city, rivers, ponds, and lakes flooded to turn the countryside into muck, and a strong air defense network had been emplaced. The Mezrehis spent the majority of July forging a ring of steel around Borsat, driving Tihaman defenders into the city proper, and using the outskirts as a base to set up operations. By September, the artillery train had caught up despite the critical lack of motor vehicles to move the guns, and 120 field artillery pieces and 74 multiple rocket launch systems were in place to begin the bombardment of the city. Tihaman special forces units continually raided these positions at night, harassing Mezrehi efforts to start the siege, so that it was postponed until mid-October before they could properly intervene. By now, air cover for the Mezrehis was worsening, and they had to make their move. Zeh Heda gave the order to begin shelling on October 30th, 1993, and Mezrehi units began to push into the city. They faced severe resistance, as a grueling house-to-house battle began in the outskirts of Borsat. By mid-November, the weather had taken a turn for the worse, as torrential rains worsened the already muddy conditions created by the defenders. Thousands of troops and civilians from all sides were overcome by disease, and al-Hattan pleaded for reinforcements from the Tihaman General Staff in Nitra. He had lost 15,000 men by the end of December, though the enemy had made little gain. However, the situation on other fronts, combined with the difficulty of reinforcing the besieged city, meant reinforcements weren’t exactly forthcoming, and al-Hattan received a trickle of reservists and miltiamen instead of the flood of regular army troops he repeatedly stated were required to lift the siege.

As 1993 turned to 1994, the situation remained largely stagnant. The city was cut off, shelled heavily, and both soldiers and civilians continued to fall victim to disease and starvation. However, some good did befall the defenders. By springtime, the Tihaman People’s Air Force had achieved total air superiority over Borsat, and the threat of Mezrehi bombing was largely abated. Tihaman aircraft also began bombing and strafing runs against Mezrehi artillery positions to the south, but these were largely ineffective due to intense Mezrehi anti-aircraft fire. As spring dawned and weather improved, resupply missions across Lake Malafon began, with Tihaman forces using motorboats to run food and other supplies into Borsat under heavy enemy fire. Only about 45% of these missions were successful, as most were destroyed or forced to turn back, but it was something, and the defenders were grateful for what they could get. However, by the start of the summer, fortunes were reversed. A renewed Mezrehi offensive by the men of the 7th. and 14th. Infantry Divisions into the southern parts of the city successfully unseated the men of the defending 54th. Workers and Peasants Militia Brigade, forcing them out of their defensive positions around the State Steelworks #47 with heavy losses, and all but obliterating the plant in the process. For the following 2 months, the slow grind continued, with Mezrehi forces paying for every foot of ground with blood, but by year’s end in 1994, they had captured the majority of the city. The war across the rest of the front had by now surpassed the battle for Borsat, which was abandoned as a lost cause by the Tihaman military anyway. A gradual withdrawal was organized out of the besieged city, and thanks to the skillful conduct of rearguard actions, over 40,000 men were successfully evacuated.

Despite the successful evacuation of Borsat, the Tihaman withdrawal threatened to become a rout as Mezrehi forces turned the Tihaman left front and broke through with a heavy armor concentration, destroying dozens of Tihaman tanks and armored vehicles in the process. Tihaman air power slowed the Mezrehi advance and suppressed their artillery, but the constant pressure maintained on the Tihamans by the Mezrehis made it difficult to organize a defense or counterattack. By early 1995, the Tihamans had withdrawn over 50 miles, with the Mezrehis in hot pursuit. The cracks in the offensive were starting to show, however, as resistance in captured territory forced the Mezrehis to commit increasingly large numbers of troops to garrison occupied areas. Furthermore, increasingly harsh reprisals against civilians in captured territory only furthered the partisan cause. Meanwhile at the front, Mezrehi armored vehicles and motorized units frequently outran their over-capacity logistics train, and the lack of motorized transports only slowed the progress of the offensive. Mezrehi armored vehicles and tanks also suffered increasingly intensive maintenance routines as a result of strenuous use and difficult conditions, which greatly reduced the number of tanks available for combat operations. By the middle of the year, Mezrehi forces had only advanced a further 10 miles, capturing several minor villages and towns with low casualties, but had failed to achieve any major objectives. The increasingly heavy Tihaman air defense network also made it difficult for the Mezrehis to support their conventional forces, and as a result they began to rely increasingly on unconventional attacks by light infantry units and insurgents under the cover of darkness.

In December of 1995, Mezrehi forces launched an attack on the Tihaman city of Al-Jaffra, 65 miles inside Tihaman territory. Attacking at night, the Mezrehis successfully crossed the river Sophrates, and encircled the city. Supreme Leader al-Hashmi made it clear to General al-Hattan that the city should not fall, and personally ordered 2 whole Corps to its defense. By now, Mezrehi 4th. and 6th. Corps were badly depleted, with only ⅔ of their armor remaining and roughly ½ their artillery still in transit. Without air cover, the Mezrehis launched an attack with 3 divisions on the Tihaman 8th. Corps, positioned on the city’s right flank, with the goal of driving it out of its strong defensive positions. However, their offensive was broken up by massed Tihaman artillery and rocket fire, and lost cohesion. Tihaman air power also chased off the Mezrehi air cover and subjected advancing Mezrehi armored columns to murderous air attacks. The Mezrehi attack was driven off after sustaining nearly 8,000 casualties over 4 days of fighting, after which al-Hattan, in a stroke of genius, chose to launch a counter-attack to deprive the Mezrehis of the opportunity to regroup and try again. On December 23rd at 4AM, Tihaman artillery and rockets announced the start of the operation, and 4 Tihaman divisions swept through the disorganized Mezrehi lines. At dawn, aircraft and attack helicopters joined in, sweeping entire armored companies from the field. The Mezrehi center collapsed, and Tihaman armored assets drove directly into the Mezrehi rear, forcing the remaining troops into pockets. After another day of fighting, 2 whole Mezrehi divisions were destroyed, and 4th. Corps was forced to abandon its positions. The Mezrehis aborted the siege of Al-Jaffra, and pulled back their forces to regroup and stall the Tihaman offensive. It was the first major victory won by the Tihamans since the start of the war, and proved the Mezrehis could be beaten. The victory was broadcasted day and night by the propaganda machine, and al-Hattan was promoted to Field Marshal as a result of his successes. The initiative was now, for the first time, in Tihaman hands, and the Mezrehis were forced onto the defensive.

Mezrehi invasion force retreats

With the Mezrehi army on the defensive for the first time since the start of the war, the Tihamans had relative freedom of operations on the Northeastern front. Widely regarded as the most important front of the war, the objective was now not only the recapture of all occupied territory, but also the destruction of the Mezrehi army in Tihama. The Mezrehis had recently reinforced their positions with additional troops and materials in an attempt to prevent a Tihaman breakout, putting their strength at around 210,000 men and 1,100 tanks across the front. By now, Tihaman military production had reached a fevered pace, and 2 whole Field Armies of the Northeastern Command Sector were arrayed against the Mezrehis, totalling 250,000 men and 2,200 tanks. The Tihamans were also helped by a flood of new equipment, including the Kardovijan-designed (K)M-33 rifle and new indigenously-designed M81 main battle tank.

After their disastrous reversal at Al-Jaffra, the Mezrehi 2nd. Army, composed of the 4th. and 6th. Corps, retreated almost 10 miles before establishing a defensive line just north of the village of Karzaa in March 1996. The Mezrehi plan was to entice the Tihamans into attacking their center, before hitting their flanks with their armor in a classic double envelopment. Unfortunately for the Mezrehis, the Tihamans were expecting this, and their main tactical discussion was how to prevent it. To this end, the Tihamans emplaced minefields, anti-tank guns and missiles, and extensive trench works along their flanks, and enticed the Mezrehis to attack them in order to use these defenses to sap their strength. The Mezrehi commander, General Zeh Heda, did just that. In the spring, as the weather improved, the Mezrehis attacked the Tihaman flanks with 2 whole armored divisions after a brief artillery barrage. Once again, the Mezrehi attack was doomed by its lack of effective air cover, allowing Tihaman close-air support aircraft and attack helicopters to devastate the advancing columns. Likewise, the lightly-equipped Mezrehi infantry units found it extremely difficult to break through the reinforced Tihaman lines, and took heavy losses. Deprived of air cover and finding it impossible to buckle the Tihaman flanks, the Mezrehis withdrew. However, they stalled a Tihaman counterattack by anchoring their flanks on higher ground, taking a page from the Tihaman playbook and entrenching with tank-killer teams and minefields and resisting fanatically. It was at this time, one of al-Hattan’s staff officers, Major-General Rahaad Aziz, presented a plan to drive the Mezrehis from their position with chemical weapons. It was a touchy situation, as use of such weapons could garner international condemnation. The Tihaman government, however, received assurances that the move would be supported by the FRB, and that the SAFN/AVA would not intervene as ending the war quickly and restoring peace to the region was more important to them than punishing Tihaman use of chemical weapons. Furthermore, the Tihamans had obtained incriminating evidence that the Mezrehis had committed war crimes of their own, and as a result would not be the first offender. So, in early April, 6 Tihaman ballistic missiles laden with sarin nerve gas slammed into Mezrehi positions at nightfall. Throughout the night, the screams of suffering Mezrehi troops carried across the trenches, and by morning the Tihamans began their advance across no-man's land. Gas mask-clad troops carrying explosives and flamethrowers reached the trenches shortly, and found them manned only by corpses. The Mezrehis had abandoned their positions as dawn broke, and the entire Mezrehi army group withdrew another 10 miles.

This was the first use of chemical weapons in the war by Tihama, and it wouldn’t be the last. Although the Mezrehi military eventually learned from their experiences and began issuing gas masks, over 60,000 Mezrehi soldiers would fall victim to Tihaman chemical munitions before the war was over. As expected, international condemnation was minimal, and the Tihamans received little more than a slap on the wrist. From this point on, chemical weapons would be a repeated feature of Tihaman operations, particularly against hardened positions that would require heavy casualties. For the remainder of the war, overwhelming firepower and use of every available technological advantage would characterize Tihaman military actions against their opponents. By the start of 1996, the Tihamans had driven the Mezrehi invasion force in the northeast back for 20 miles, and were poised to retake Borsat, the seat of the Mezrehi occupation government.

Tihaman invasion of Yehosa

It was around this time that the Tihaman Government and Central Military Commission began seriously discussing plans for an invasion of the Shehari Republic of Yehosa. An ideological twin of the Mezrehi state, Yehosa had been a major supporter of the Mezrehi war against Tihama since the beginning. Over 20,000 Yehosan troops were serving in the Mezrehi armed forces as volunteers, and the country had acted as a third-party buyer for the Mezrehis, purchasing military equipment overseas before transferring it to their allies. Supreme leader al-Hashmi stated to his generals during a meeting of the Commission and Party leaders that “this rat’s nest of bandits and war profiteers must be destroyed”, and ordered his top commanders to prepare for an offensive against Yehosa. From the start, the campaign looked to be an easy victory for Tihama. An entire field army, plus another 2 Corps size units of Border Guards and Red Guards units were earmarked for the assault, totalling ~150,000 men supported by 900 tanks, 170 fixed wing aircraft and 80 attack helicopters. Arrayed against them, the Yehosan Defense Forces could muster only about 50,000 standing troops, plus another 75,000 militia and paramilitary personnel. The tiny country also had only small armored and air assets, and in the event of an invasion would rely almost entirely on the Mezrehi military for support. Despite their recent overseas buying sprees on behalf of their allies, they had made very little effort to acquire it for their own military, believing that Tihama was overstretched by the Mezrehi assault and would not widen the war into their territory.

That being said, it should come as no surprise that the Yehosan military was caught totally off-balance when a savage Tihaman assault ripped across the frontier between the two states in fall of 1996. The overall commander of the Tihaman invasion, General Gaad Hasaji (former Chief of Staff to the late Field Marshal Hassan), emphasized speed and rapid advance above everything else, bypassing fortified objectives with his armored forces and leaving the infantry to mop up encircled pockets of troops. The operational objective of the Tihaman offensive was to slice through the center of Yehosa, cutting off pockets of troops and destroying entire combat units, and reach the opposite coast in order to seize vitally important ports used for shipping in material for the Mezrehi war machine. As the ground offensive commenced, an air campaign swept across the country. Tihaman fighter-bomber and ground strike aircraft began a wave of strikes and bombardments across the country, targeting radar arrays, anti-aircraft defense installations, and Yehosan ground forces. On the first day, ~200 armored vehicles, 450 trucks and utility vehicles, and 500 anti-aircraft guns and missile emplacements were destroyed. Simultaneously, air-launched cruise missiles and guided bombs struck Yehosan command and control facilities, including the headquarters of the Yehosan general staff in the capital city of Marasuf. This was the first time weapons of this type were deployed by the Tihaman People’s Army Air Force during combat operations, and they proved highly successful.

On the ground, lightly-equipped Yehosan security forces were brushed aside by the vanguard of the Tihaman invasion force, which were among the most modern armored units of the army. The flat Yehosan terrain was also perfect for armored operations, and in the first few weeks large pockets of Yehosan troops were encircled by the Tihamans. Along the northern axis of advance, most of the fighting was carried out between Yehosan paramilitary territorial militia forces and Tihaman Red Guards units, which resulted in a back-and-forth shoving contest where both sides traded ground while large swathes of land were captured by the regular forces further south. The fighting in the north was bitter and fierce, and soon bogged down into a trench warfare-style scenario. The Tihamans repeatedly bombed Yehosan defensive positions from the air to make up for the lack of heavy equipment provided to the Red Guards units, but they continually failed to achieve a breakthrough in the face of fanatical Yehosan resistance. By the summer, the bulk of southern Yehosa was secured, and the Mezrehis had failed to reinforce their allies in order to prevent the fall of their strategic ports, only offering sporadic strikes on Tihaman forces from the air. The success further south freed up Tihaman heavy maneuver units to begin assisting the Red Guards in pressing the offensive towards Marasuf, and after months of heavy fighting the Yehosan/Mezrehi defenders gave way and withdrew to the capital. They fought a series of skillful rear-guard actions as they fell back, inflicting noticeable damage to the advancing Tihaman armored columns, but time and time again superior Tihaman firepower and air support forced the defenders back. By the time the Tihaman 7th. Corps-which was tasked with the capture of Marasuf-could besiege the capital city, the defenders had transformed it into a formidable defensive position. Frontal assault was out of the question, as the hilly terrain surrounding the city had been utilized to create a landscape that made mechanized assault virtually impossible. Yehosan and Mezrehi defenders had emplaced minefields, tank-killer teams, machine gun nests, and artillery pieces in a 15-mile perimeter around the city and prepared to resist to the death. Two separate Tihaman offensives faltered and collapsed with heavy losses, particularly amongst the Red Guards units. General Hasaji then resolved to begin a conventional siege of the capital, and brought up the heaviest guns available to the army. Furthermore, ballistic missiles began falling into the city almost indiscriminately, while infantry supported by merciless airstrikes and attack helicopters began systematically clearing a path through the surrounding defenses. All the while, the Tihaman People’s Army Navy began a blockade of Yehosa, particularly around Marasuf, and began striking the city with naval gunfire and missiles. An amphibious landing operation to the north of the city inserted two whole battalions of naval infantry which made slow but steady progress against heavy resistance.

The fall of Yehosa

During the siege of Marasuf, the commander of the Tihaman 4th. Air Army Colonel-General Hamid Arkazi began a terror-bombing campaign against the city. His hope was that bombing the local population would sap support for the defenders and force them to surrender, however it garnered Tihama considerable foreign attention. SAFN and FRB diplomats alike urged Tihama to step down and sign a separate peace with Yehosa, as well as allow an international force into the country to occupy the capital and surrounding areas in order to ensure a peaceful transition. Initially, the Tihaman government vehemently opposed the involvement of international forces as an act of “foreign imperialism”, but relented and conceded after every FRB state except Rossnia agreed to join the international peace effort. 5,000 military personnel from the SAFN and FRB, with observers from the AVA, were inserted via aerial and amphibious landings and moved quickly to disarm the Yehosan armed forces as well as establish a frontier with the advancing Tihaman army. Yehosa ceased to exist as a country by the end of the year, and as 1997 started the International Legations of Al’Artadal was established as the regional provisional authority.

1996-2000: Interlude

The savagery of the Shehari War had thoroughly shocked the world as a whole. Everything had happened in such a rush that most leaders will still struggling with how to deal with the conflict. Immediately, the primary concern of leaders from both the OFSN and FRB was that nuclear weapons and chemical munitions would be used by Tihama on a wider scale to retaliate for the invasion. Thankfully, Tihama's leadership had been under immense pressure from their FRB backers not to use nuclear weapons for fear of provoking an OFSN response that would widen the conflict. As a result, after the fall of Yehosa in 1996, FRB and OFSN forces invited both Tihaman and Mezrehi delegates to the former Yehosan capital of Marasuf, now the capital of the International Legations of Al' Artadal, to discuss a ceasefire.

Initially, both sides resisted the idea of concluding the war. Tihama wanted total annihilation of the Mezrehi military, while Mezrehi commanders wanted to launch a renewed counteroffensive back into Tihama to force a favorable peace settlement. However, logic and reason prevailed. Despite their recent successes against Mezrehi forces, Tihama's commanders knew that they had gotten lucky and that their victories had more to do with enemy incompetence than their own martial prowess. Indeed, Tihama had been caught almost entirely off-guard and unprepared, and even after 3 years of conflict the armed forces were not at peak efficiency. Furthermore, a multitude of military units were depleted of both manpower and equipment on both sides, necessitating time to replenish them. The Mezrehi invasion force had lost over half its tanks and armored vehicles to attrition and enemy action, and an increasingly efficient Tihaman People's Army Air Force was wreaking havoc on Mezrehi air assets and ground units alike.

Delegates met in Marasuf on December 17th, 1996, and began a weeks-long negotiation process. At first, neither side would concede anything, refusing to accept a status quo. Tihaman delegates demanded that restrictions be placed on the size and weaponry of the Mezrehi armed forces, while Mezrehi leaders demanded the liberation of Yehosa and disarmament of Tihama. Eventually, OFSN leaders accepted an FRB proposal for a ceasefire that recognized Tihama's annexation of Yehosa in exchange for Tihama's allowance of the establishment of the International Legations of Al'Artadal under international governance. Furthermore, Tihama reluctantly agreed to drop all demands for Mezrehi disarmament, in exchange for the establishment of a demilitarized zone across the border of the two states. The ceasefire went into effect on January 1, 1997, with forces from all sides withdrawing their troops across the 5-mile DMZ demarcation line along the pre-war border.

Rearmament and preparations: Tihama

It was no secret neither side intended to honor the ceasefire forever, as both Tihaman and Mezrehi delegates threatened eachother as they left the ceasefire negotiations. Therefore, Tihama's FRB allies immediately went into overdrive to help their friends prepare for the hostilities they knew would eventually resume. The UFRR sent a huge military training and assistance mission to Tihama. It was dedicated to improving the efficiency of all Tihaman service branches: on the ground, UFRR advisors worked closely with their Tihaman counterparts to reorganize units for maximum efficiency, and vastly improved small-unit tactics, close-air support and artillery coordination with ground forces, and drilled Tihaman officers in good battlefield strategies. In the air, the previously-installed training mission continued their important work refining Tihaman maintenance routines to ensure peak aircraft availability, instructing Tihaman pilots on proper dogfighting tactics and ground-support missions, and even schooling Tihaman bomber pilots on strategic bombing and target identification. At sea, Tihaman forces conducted huge naval drills with FRB naval units from the UFRR, Baclia, Nurmandria, and Daehan, the goal of which was largely to intimidate enemy naval forces. Carrier aviation drills were among the most practiced aspects of the exercises, as Tihaman jet pilots prepared themselves to strike ground and naval targets from the aircraft carrier Tihamat Alhambra.

To further ensure future victory, the FRB directed billions in military aid and assistance to Tihama. Over 500 tanks, 700 IFVs, 1,100 APCs, 500 self-propelled guns, 1,200 towed artillery pieces, 200 towed and 400 mobile multiple rocket systems, and countless rifles, machine guns, RPGs, MANPADs, and ammunition were supplied to Tihama by a variety of FRB states. The UFRR also leased over 100 aircraft at a heavily discounted rate to the TPAAF, with an option to purchase them after 5 years (Tihama was not obligated to pay to replace lost airframes.) To ensure the good graces of the Tihaman government in order to further their oil exploration interests in the country, the Remanian government forgave Tihaman debts and continued to trade raw materials and manufactured goods with the country, despite condemnation from their OFSN partners.

Tihama's armies were reinforced and redeployed, with a host of new equipment from both domestic factories and overseas suppliers, and replenished by a wave of new recruits. By 2000, the TPA numbered just over a million men, over half of which were now stationed along the Mezrehi DMZ. Two field armies and 3 army corps, of which two were newly-formed, were now within striking range of Mezrehi territory. In addition, over two dozen ballistic missiles of the Strategic Rocket Forces had been moved towards the border region, and could strike targets anywhere within Al-Mezreh. Two air armies were stationed near the border as well, with over 450 aircraft between the two of them earmarked for operations over Mezrehi territory. The rest of the TPAAF was retained either in reserve or for operations over Tihama proper to defend against Mezrehi raids.

Rearmament and preparations: Al-Mezreh

Al-Mezreh had the disadvantage throughout the conflict of being without major international backers, and thanks to international condemnation were forced to either smuggle in military equipment and spare parts or use other nations as third-party buyers. With the loss of Yehosa, this was made even more difficult. Fortunately for the Mezrehis however, there was an emerging player in the field of global geopolitics with a vested interest in their survival: the Republic of Estry. Eager to exploit hydrocarbon and mineral deposits in Al-Mezreh to compete with the Remanians, Estry promised the Mezrehi government support in exchange for unchallenged drilling and mining rights within Al-Mezreh. Desperate to replenish their equipment stocks, the Mezrehi government agreed. Estry could not yet outright supply the Mezrehi armed forces with equipment directly, but agreed to act as a third-party buyer for foreign equipment. Operating through front agencies and corporations to avoid international scrutiny, Estrian agents supplied Al-Mezreh with over 100 tanks, dozens of APCs and armored cars, and thousands of MANPADs, RPGs, ATGMs, and small arms. It was a far cry from what Tihama had received from its allies, but it was something, and the Mezrehi military was thankful for what they could get. The Mezrehi Navy also acquired plans for midget submarines from Estrian engineers, and went on to build no less than 10 of their own that would serve in the coming conflict with some success. Furthermore, Estrian pilots were sent to Al-Mezreh as volunteers to train and support the outnumbered and outgunned Mezrehi Air Force.

Nobody believed the Mezrehi Armed Forces would have performed as well as they did against an adversary so much larger and better-equipped. Invading Tihama taxed the Mezrehi forces to the absolute limits of their capabilities, and they knew it. Losses had been heavy, with much of their heavy equipment now destroyed or captured and thousands of their troops taken prisoner. The Mezrehi leadership knew changes would have to be made if the nation was to survive, and therefore they adopted an entirely new philosophy. In order to minimize the Tihaman advantage in men and equipment, Mezrehi forces would dig in and establish a defensive line at the DMZ to cause as many casualties to Tihaman forces as possible. It was believed that this would weaken Tihaman units to the point where they could then be broken up by multi-pronged attacks from Mezrehi troops using unconventional tactics on friendly territory. The Mezrehi Ground Forces moved 7 divisions to the vicinity of the DMZ and began digging in, emplacing hundreds of artillery pieces, anti-tank obstacles, and hundreds of miles of minefields and anti-tank ditches. Bridges were blown up and bodies of water flooded to make the area more difficult for advancing troops, while tanks were dug in and machine guns emplaced overlooking kill zones.

The fault of the Mezrehi defense plan was that both air cover and air defenses were insufficient to support the defensive line being constructed, and that no contingency plan was in place for if the line was breached-a fault which would come back to haunt Mezrehi commanders. Nevertheless, by 2000 the Mezrehis had replenished their forces to nearly 400,000 men along the DMZ, 1,100 tanks, 750 artillery pieces and rocket systems, and 250 aircraft near the border.

2000-2004: The second phase

After four years of peace, the global community had high hopes for a negotiated solution to the conflict between Tihama and Al-Mezreh. On the morning of November 19th, 2000, those hopes were drowned out by the sound of gunfire. That night, a firefight had erupted between Tihaman and Mezrehi troops stationed along the DMZ between the two states, as Mezrehi forces crossed into Tihaman territory to pursue an escaped prisoner. What began as a skirmish (which were quite common over the past four years) evolved into a battle as Mezrehi forces knocked out a Tihaman APC with an improvised grenade, and Tihaman forces opened fire with 23mm autocannons which killed 16 Mezrehi troops. The Tihaman government called the incident an attack on Tihama's sovereignty and a violation of diplomatic agreements regarding border jurisdiction, and the following morning the Tihaman military began following its prepared invasion plans, thrusting into Mezrehi territory supported by overwhelming firepower.

TPAF aircraft launched a wave of attacks with their new arsenal of precision-guided munitions; within a matter of hours, the Mezrehi capital of Qatif had been hit by a series of savage aerial assaults. The Mezrehi Air Force headquarters in particular was hit by two 1,500lb guided bombs dropped by Tihaman AALA-86 fighter-bombers, devastating the building and killing over 1/3 of its occupants. In addition to a calculated campaign of airstrikes and bombings, Tihaman ground-based ballistic missiles slammed into Mezrehi cities indiscriminately and caused mass panic among the civilian population. The Tihamat Alhambra carrier strike group launched its aircraft against targets in Al-Mezreh, striking key port facilities and targeting offshore oil facilities operated by Mezrehi and Estrian companies- a move which led to substantial condemnation from the international community as the resulting environmental disaster wreaked havoc on the ecology in the region. Simultaneously, Tihaman submarines launched a series of attacks against Mezrehi shipping, and in the first day alone five Mezrehi-flagged cargo vessels and oil tankers were hit by Tihaman submarine attacks.

The Mezrehi Ground Force remained in its dug-in positions, and when the Tihaman attack came they found the going difficult among many sectors of the front. Well-served anti-tank guns and carefully emplaced minefields took their toll on Tihaman armored and mechanized columns, and by the end of the first week progress was negligible, limited to the capture of a few border towns and villages. Nevertheless, the havoc being wreaked behind the front lines by the relentless Tihaman air campaign threatened to undermine the valiant Mezrehi ground defense. Overwhelming air superiority made it increasingly difficult for the Mezrehis to defend their positions, and before long a series of holes began to form in the Mezrehi front lines. The Holy Martyrs offered the heaviest resistance, and melted into the rear of the advancing Tihamans to harass and attack lines of supply and communications, forcing the Tihamans to devote troops to the defense of second-line areas.

Nurmandrian intervention

Relations between Al-Mezreh and their neighbors to the south in Nurmandria had never been excellent, but in recent years they had deteriorated to the point of near-hostility as Al-Mezreh attempted to subvert the secular Nurmandrian state with it's own religious ideals. As a result, it was no surprise to the Tihamans when the Nurmandrian ambassador came walking in their door asking if the Tihamans needed assistance in their defeat of Al-Mezreh. Normally, Al-Hashmi and the rest of the Tihaman leadership would have refused, but faced with a savage Mezrehi counterattack and fanatical resistance both at the front and behind the lines, they reluctantly agreed. A meeting occurred between Supreme Leader Al-Hashmi and his aides and the Nurmandrian ambassador, Abdhul Murawan, and his delegation at Al-Hashmi's tropical beach retreat in Northeastern Tihama on April 14th, 2001. After lengthy debate, post-war demarkation lines and zones of occupation were drawn up, and both sides agreed to pursue a more or less unified plan of operations against the Mezrehi threat. Murawan promptly phoned his superiors and informed them an agreement had been reached, after which the order was given to mobilize an already-prepared response force. Two corps-size units of the Nurmandrian army totalling ~115,000 men had been earmarked for combat operations against Al-Mezreh, supported by 500 tanks and 230 aircraft and helicopters. The Nurmandrian plan was quite simple: a string of border posts would be destroyed and villages seized to clear the way for the capture of the border city of Kharj, which controlled the largest trade intersection in southern Al-Mezreh. Simultaneously, Nurmandrian aircraft would take off with precision-guided munitions with orders to destroy key dams and bridges in southern Al-Mezreh, crippling power and transit infrastructure across the region. The Nurmandrians figured that if they could cause enough disorganization and panic in southern Al-Mezreh, they would quickly take a seat at the negotiation table without Nurmandrian forces having to thrust deep into Mezrehi territory and risk becoming bogged down or cut off.

Despite their superiority in firepower and technology, the Nurmandrians hadn't fought a major war in years, and many of their front-line troops were inexperienced reservists with no practical combat experience. Unfortunately for Nurmandria, the area of their advance was garrisoned by Mezrehi troops resting and replenishing from the front with Tihama-as a result, the Nurmandrians met freshly-replenished, battle-hardened units about to head back to the front lines. The lead units of the Nurmandrian invasion force (IV Corps under General Adam Mussal) were badly mauled by accurate artillery and small arms fire from the Mezrehi 9th Infantry Brigade, while armored vehicles of the 13th. Cavalry Division wheeled into the Nurmandrian flank and forced them into a withdrawal to avoid encirclement. Further west, the other prong of the Nurmandrian advance (VII Corps under General Mikhail Maraqiwii) found the going more easy, and pushed aside Mezrehi border guards units and captured a string of lightly-defended villages. By the end of the first day, they had pushed 35 miles into Al-Mezreh and captured some 1,500 prisoners. The air assault also met with more success, as it coincided with a wave of Tihaman bombings and missile strikes which totally overwhelmed Mezrehi air defenses. The Al-Ghar dam in southeastern Al-Mezreh was hit by a pair of Nurmandrian heavy concrete-piercing bombs and destroyed, leaving over a million people without power and causing a flood which devastated a significant portion of the region's farmland. Of course, this had the added affect of slowing down the advance of the invasion force by demolishing roads and bridges and reducing the countryside to a quagmire. Mezrehi forces fought fanatically in these adverse and hostile conditions, but before long they were exhausted and short on ammunition. Additionally, they needed to be badly rotated with units facing Tihama to allow troops on that front to rest and re-arm. The Mezrehi spring counteroffensive of 2001 was defeated with heavy losses by the Nurmandrians, over 50 tanks were destroyed or knocked out, and 3,000 men killed with another 7,000 captured. By the start of summer 2001, the Nurmandrians were in a secure position to renew their advance, bridges were built and engineers had cleared paths for armored vehicles, while the Nurmandrian Air Force maintained a regular bombardment of the defenders to break up any potential counterattacks.

Mezrehi summer counteroffensive

While the war raged against Nurmandria in the south, to the north Mezrehi forces had been making a valiant stand against the Tihamans. Progress was slow, but steady, yet the Tihamans suffered heavy losses in men, fuel, and material and by June 2001 they badly needed a rest. Tihaman units paused their advance across most of the front on June 30th, 2001, with the goal of giving the men time to rest while fresh material was brought up from the rear. Air and missile strikes against key Mezrehi targets and cities continued, and artillery bombardment of Mezrehi units on the front was near-constant. However, in the face of such firepower, Mezrehi forces launched a hastily put-together counterattack on the night of July 14th. Under the cover of darkness, just as they'd invaded Tihama, Mezrehi units mounted a string of raids and assaults across the Tihaman front line. Unfortunately for them, this was not the same war they had fought a few years ago. Tihaman units both on the ground and in the air had been receiving thermal-imaging and night vision systems both of domestic manufacture and from FRB partners, and put it to good use against the Mezrehi troops advancing at night. Tihaman helicopters equipped with thermal-imaging systems and carrying rockets and cannon pods shredded advancing troop columns, and dozens of armored vehicles were destroyed or disabled. None the less, Mezrehi troops pressed on into the following day and managed to recapture some 15 miles of ground from the Tihamans, raising their flag on the recaptured village of Herza on July 17th. Al-Hashmi was furious and railed against his commanders, from whom he demanded action. Several Tihaman units were withdrawn and replaced by fresh troops from other sectors of the front. Amongst the units rotated into combat was the 7th Guards Tank Division, one of the most elite and lavishly-equipped formations in the Tihaman army. Equipped with Sofiae Commonwealth-made M9 and locally-produced M-73TK main battle tanks, as well as the locally made M-46 infantry fighting vehicle, the unit was pound for pound better equipped than any of their peers in the Mezrehi army.

The Tihaman counterattack plan was put into action on the morning of August 1st, 2001. 7th. Guards Tank Division armor rolled through the Mezrehi flanks with the goal of encircling the recently retaken village of Herza and forcing the Mezrehis into a pocket. Over the past week, the Mezrehi 19th. Infantry Brigade and 21st. Mechanized Brigade had fortified the village with trenches, berms, and emplaced tanks and machine gun positions. Though it was strategically insignificant, the village became the site of a political struggle and a battle for prestige. Overnight before the assault began, the village was subjected to withering air and artillery bombardment, as Tihaman aircraft equipped with infrared targeting equipment dropped laser-guided bombs on the village and long-range artillery and MLRS batteries rained fire onto the enemy. Mezrehi artillery attempted counter-battery fire but without accurate fire control protocols and blinded by the darkness of night, they failed to sufficiently suppress the Tihaman batteries. 414th. Mechanized and 196th. Armored brigades of the Tihaman 7th. Guards Tank Division wheeled around to the Mezrehi north and crashed through the defenders as dawn broke, breaking into their rear and forcing the entire Mezrehi right flank to break formation and reposition. Meanwhile to the south, Mezrehi 47th. Infantry Brigade was being badly battered by a frontal assault by Tihaman 177th. and 209th. Mechanized Brigades. The Mezrehi commander, General Seyyed, hastily rushed the under-strength 79th. Holy Martyrs battalion into the fray to reinforce the buckling 47th. Engaging in human wave-style tactics, they managed to slow the Tihaman advance long enough to pull the 47th. Infantry Brigade back and replace them with the 19th. Armored Brigade. Equipped with some of Al-Mezreh's best armor, they stopped the Tihaman advance and engaged in a counterattack just three days later, but this was swatted off with liberal use of air power and tank hunter helicopters. All the while, the Mezrehi Air Force fought a desparate battle for control of the airspace above the battlefield. Outnumbered almost 2:1, Mezrehi pilots had the advantage of possessing a small number of Estrian-supplied Ch-9EST 4th-generation fighters at their disposal. On paper, these were better than anything flown by the Tihamans and indeed captured examples would heavily influence later Tihaman aircraft design, but the Mezrehis used them sparingly and as a result they failed to gain air superiority over Herza. After about a week of hectic fighting, the Mezrehis had withdrawn from the area, but not before leaving 47th. Infantry, 79th. Holy Martyrs, and 22nd. Cavalry trapped in the village and under siege by the Tihamans. A poorly-organized relief mission failed to break through to the besieged units, and after another month of grueling siege warfare, starvation and disease forced the Mezrehis to surrender. Some 15,000 men were captured, the largest surrender of Mezrehi troops on their own territory since the war had resumed. As the gravity of their worsening situation set in, Mezrehi leaders increasingly pressed their generals to deliver results, which resulted in frustrated officers often forcing their men into battles they couldn't win and resulted in further casualties and material loss. By the end of 2001, the Mezrehis had surrendered about 50 miles of their own territory since the start of the year as the Tihaman offensive slowly pushed into their country, simultaneously fighting a rear-guard action against Mezrehi paramilitary and civilian resistance. As the Tihamans and Nurmandrians both pushed into Mezrehi territory, the going was tough and increasing losses of life would soon lead to a re-evaluation of operational tactics and goals.