Mejico

Mejican Empire Imperio Mejicano (Spanish) | |

|---|---|

Placeholder image. | |

| Capital and largest city |

Mejico City |

| Official languages | |

| Recognized regional languages | 108 Amerindian languages, 11 European languages, and 3 Asian languages |

| National language | Spanish (de facto) |

| Ethnic groups (2024) | |

| Religion (2022) |

|

| Demonym(s) | Mejican |

| Government |

Unitary executive monarchy |

• Monarch | Agustín VI |

| Gabriel Ricardo Quadri de la Torre | |

| Lorenzo Xicoténcatl de Vargas Copeticpac | |

| Gerardo Lehmann Guzmán | |

| Daniel Borzyszkowski | |

| Legislature | Congress |

| Senate | |

| Chamber of Deputies | |

| Independence from Spain | |

• Granted | 2 September 1788 |

| 28 December 1825 | |

| 20 November 1910 | |

| 16 October 1966 | |

| 22 September 1984 | |

| Area | |

• Total | 4,266,364.5 km2 (1,647,252.5 sq mi) (4th) |

• Water (%) | 3.07 (as of 2015) |

| Population | |

• 2024 estimate | 307,697,417 (5th) |

• 2020 census | 290,893,467 (4th) |

• Density | 66.61/km2 (172.5/sq mi) (122nd) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2022 estimate |

• Total |

|

• Per capita |

|

| GDP (nominal) | 2022 estimate |

• Total |

|

• Per capita |

|

| Gini (2018) |

medium |

| HDI (2021) |

very high · 86th |

| Currency | Iberian peseta (IBP, ₧) |

| Time zone | UTC−8 to −5 (See Time in Mexico) |

• Summer (DST) | UTC−7 to −5 (varies) |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +52 |

| Internet TLD | .mj |

Mejico (Spanish: Méjico, /ˈme.xi.ko/, English pronunciation: /ˈmɛ.d͡ʒɪ.koʊ/), officially the Mejican Empire (ME; Spanish: Imperio Mejicano, IM), is a country located in the southern portion of North America. It is bordered to the north by Louisiana and Oregon; to the south and west by the Pacific Ocean; to the southeast by Central America and the Caribbean Sea; and to the east by the Gulf of Mejico. Covering over 4.25 million square kilometers, Mejico is the 2nd-largest country in the Americas by total area and the 4th-largest independent state in the world. With an estimated population of over 274 million people, Mejico is the 4th-most populous country in the world, it has the most Spanish-speakers, and is the most populous independent nation in the Americas.

The Mejican Empire is an executive monarchy. The current monarch is Agustín VI of the House of Bourbon-Iturbide, who reigns since his father's death in 2014. The current President of the Government is Gabriel Quadri de la Torre, who has served since his election in 2020. The Imperial capital is Mejico City, which is classified as a global city and has a metropolitan population of 26,028,884. Other metropolises in the country include Los Angeles, San Francisco, Santísima Trinidad, Veracruz, Espíritu Santo, Guadalajara, Monterrey, Alcalá de Argüello, Santa Valburga de Osdo, El Paso del Norte, Puebla, San Antonio de Béjar, Sacramento, Acuña, Las Vegas, among others.

Human presence in pre-Columbian Mejico goes back to 8,000 BC and is identified as one of six cradles of civilization. In particular, the Mesoamerican region was home to many intertwined civilizations; including the Olmecs, Toltecs, Teotihuacans, Zapotecs, Mayas, Mexica, and Purépecha before first contact with Europeans. Last were the Aztecs, who dominated the region in the century before European contact. In 1521, the Spanish Empire and its indigenous allies conquered and colonized the territory of the Aztec Empire from its politically powerful base in Mejico-Tenochtitlan (now part of Mejico City), which was administered as the Viceroyalty of New Spain. Over the next three centuries, Spain and the Catholic Church played an important role in expanding the territory, enforcing Christianity, and spreading the Spanish language throughout, converting millions of Indigenous people to the faith in the process. With the discovery of rich deposits of silver in Zacatecas, Guanajuato, and San Luis Potosí, New Spain soon became one of the most important mining centers worldwide. Wealth coming from Asia and the rest of the New World helped connect New Spain to the proto-globalized economy, contributed to Spain's status as a major world power for the next centuries, and brought a price revolution in Western Europe. The colonial order came to an end in the late 18th century with the Spanish plans for American independence of the Count of Aranda, resulting in the independence of New Spain under the leadership of Gabriel I, one of King Carlos III's children, who was crowned in 1788.

Mejico's early history as an independent nation was mostly marked by political and socioeconomic prosperity, but witnessed small wars, including Yermo's Rebellion in 1808 and a confrontation between supporters of Fernando VII of Spain and Napoleon Bonaparte. Together with this, struggles in the Central American region, including its secession in 1838, and the Iturbidist Coup of 1825 were pivotal points of Mejican history. The rise of the House of Bourbon-Iturbide was accompanied by the rise of the legitimist Gabrielists, ideological conflict between Liberals and Conservatives, and border clashes with the British Empire.

In the mid-19th century, gold was discovered in San Fulgencio, prompting a gold rush and mass migration and modernization of the region. Mejico also faced the Yucatán Caste War, a racial war which saw the brief independence of a theocratic government in Chan Santa Cruz and the crushing of the rebellion by Miguel Miramón, who was proclaimed Duke of Bacalar. More conflict between Liberals and Conservatives led to the Liberal Insurgency of 1868, which was defeated five years later. Despite the Catholic Social Movement softening Conservative positions in multiple stances, the Liberal Trentennium would begin in 1880, a period of accelerated growth, economic stability, scientific development, and significant foreign investment, as well as the dominance of "Los Científicos", a group of technocrats closely affiliated to Porfirio Díaz, who exerted a very significant degree of influence on his successors. This would be the basis for the uprising of Francisco I. Madero in 1910, effectively kickstarting the Mejican Civil War.

The Mejican Civil War saw power change hands on multiple occasions. After the victory of Madero, he was proclaimed President, but he would be betrayed and murdered by Victoriano Huerta in an episode known as the Ten Tragic Days. Huerta established a military dictatorship, and his tenure saw the rise of the Constitutionalist movement, spearheaded by Coahuila governor Venustiano Carranza, who proclaimed the Plan of Guadalupe in 1913, and overthrew Huerta in April 1914. During this time, two major rebellions were occurring throughout the rest of Mejico, including that of Zapata in the south, the Flores Magón brothers in the Fulgencines, and Guttmacher in Tejas. Villa and Zapata, together with their followers, signed an alliance after their delegates were not invited to the Convention of Mejico City, but they were both killed by 1915 and 1919, respectively.

Carranza drafted the Constitution of 1917, and focused on putting down the other rebellions. Zapata was assassinated in 1919, the Magonists were dealt with by May of the same year, and the Guttmacherites managed to strike a peaceful agreement with the Treaty of Huavaco. After favoring a politically irrelevant civilian, Carranza enraged the Obregón, Calles and de la Huerta, who launched the Plan of Agua Prieta, and overthrew and assassinated Carranza on May 1920. After de la Huerta's interim presidency, Obregón became President and adopted a more Socialist stance, causing indignation among global powers, and signing the Treaty of Bucareli, which disparaged de la Huerta. He launched a short-lived rebellion and was quickly defeated in Tabasco, exiling himself to the Communard Republic of North America. In 1924, Calles became President, a very controversial figure among Mejican Catholics due to his anti-clerical laws, which gave rise to the Christiad and his subsequent assassination in 1928. After the election and death of Larrazolo in 1928 and 1930, respectively, José Vasconcelos was elected President.

Vasconcelos became increasingly authoritarian, blending Old World philosophies with his own, emphasizing colelctivism, national rejuvenation, and his concept of Castizaje. Vasconcelos supported closer ties with nationalist governments of Europe following the 1939 Euroean Spring of Nations, but disparaged the German and Italian philosophies of racial supremacy, focusing instead on La Raza Cósmica which was, in his vision, the race of the future. This era was also characterized by strong cooperation between the dictator and the monarch and religious traditionalism, having welcomed the royal family back into the country and re-establishing old privileges and Church institutions to their former power. In 1941, war erupted between Mejico and the CRNA in a brief but brutal war that saw the destruction of the Communard regime and the restoration of the Louisianan Royal Family. Having established a strong cult of personality and entrenching his ideology on the Mejican mainstream, Vasconcelos passed away in 1959, giving way to his right-hand man, Salvador Abascal.

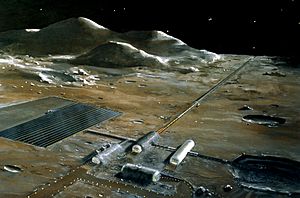

Abascal promoted a Synarchist philosophy, and continued to closely cooperate with the Mejican monarchs, who came to name themselves Emperors, and were internationally recognized as such. He promoted the culture of the Mejican people and protected their national identity, as well as the country's economic and military interests. He greatly increased Mejican influence abroad, turning the Office of Iberoamerican Education into a true powerhouse as the Hispanoamerican Union, founded in 1967, and reaching the Moon in 1966. Abascal pursued demographic, educational, military and infrastructural reforms, perpetuating the Mejican Miracle under the corporatist system that had been previously set up by Vasconcelos, becoming one of the world's largest economy.

Despite Mejico's economic boom, it still faced hardships and protests, which Abascal put down brutally. He eventually resigned from power in 1970, paving the road for the re-democratization of Mejico. However, this restoration would be brief, as elected-President Ricardo Nixon was shot and killed in 1976, plunging the country into chaos once more. On 22 September 1976, Fernando II, then Prince Imperial, gave the Zócalo Speech, declaring his father the absolute ruler of Mejico and becoming Emperor the next year, a period known as the Absolutist Octennium. During this period, Mejico confronted uprisings in multiple provinces, and saw Fernando take a heavy-handed approach towards all dissent and crime. In 1984, Fernando designated Pablo Madero to become temporal administrator in order to prepare the country to resume democratic elections the following year. Since then, Mejico has seen multiple democratic elections, that have been mostly considered safe and legitimate.

Reducing the public debt, stabilizing the financial system, women's labor rights, the American Free Trade Agreement, the Chiapas Conflict, Inquisition disestablishmentarianism, social welfare, nuclear power, the H1N1 influenza pandemic, high-speed rail, Iberoamerican politics, military expansion, space policy, Universal Basic Income, the expansion of AVEMEX, and anti-corporatism have all been at the forefront of Mejican politics since de-autocratization in 1984. Since January 2023, Mejico has been involved in an invasion of Central America, after months of rising tensions and military buildup in the country. It currently occupies a significant portion of Central American territory, and has carried out referendums on annexation of land.

Mejico has the 4th-largest GDP by purchasing power parity. The Mejican economy is strongly linked to those of its 1994 American Free Trade Agreement (AFTA) partners, especially British North America and Brazil. In 1966, Mejico became the first Iberoamerican member of the OECD. It is also a founding member of the Iberoamerican Commonwealth of Nations, a National-Catholic international community together with other Iberoamerican nations, Spain, the Philippines, and the rest of the Lusosphere. Mejico is classified as an upper-income country by the World Bank and an industrialized country by several analysts, while also being considered a superpower. Due to its rich culture and history, Mejico ranks first in the Americas and seventh in the world for the number of LONESCO World Heritage Sites. Mejico is an ecologically megadiverse country, ranking 4th in the world for its biodiversity. Mejico's rich cultural and biological heritage, as well as varied climate and geography, makes it a major tourist destination: in 2018, it was the 2nd most-visited country in the world, with over 86 million international arrivals. Mejico is a member of the League of Nations (LON), the World Trade Organization (WTO), the G20, the Security Council of the LON, and the APEC forum.

Etymology

Méjico is a toponym of Nahuatl origin whose meaning is disputed. It derives from the word Mēxihco (IPA: [meːʃiʔkoˀ]), which designated the capital of the Mexica. According to Bernardino de Sahagún, writing in the 16th century, who is the oldest documentary source, the wourd would mean "the place of Mexih", from Mexitl where metl means maguey, cihtli means hare, and -co is a locative. Mexih or Mexitl, who was a legendary Nahua priest, led his followers in the search of an eagle on a cactus for the foundation of his city after abandoning the also legendary Aztlan.

However, currently the most widespread version about the meaning of the word is "the navel of the moon" or "the place of the lake of the moon", from Mētzxīcco, mētztli (moon), xictli (navel, center) and -co (locative), according to Cecilio Robelo and Alfonso Caso. Sahagún writes the origin of the word as follows:

"This Mexica name was formerly said mecitli, being composed of me, which is metl, for the maguey, and citli for the hare, and thus it would have to be said mecicatl, and changing the c into x it is corrupted and said mexicatl. And the cause of the name according to what the old people tell, is that when the Mejicans came to these parts they brought a leader and lord who was called Mécitl, who after he was born they called him citli, hare; and because instead of a cradle they raised him in a big stalk of a maguey, from then on he was called mecitli. ... And when he was a man he was a priest of idols, who spoke personally with the devil (Huitzilopochtli), for which he was held in much respect and obeyed by his vassals, who, taking their name from their priest, were called mexica, or mexicac, as the ancients tell it".

Francisco Xavier Clavijero suggested that the toponym should be interpreted as "in the place of Mexihtli", that is, of Huitzilopochtli, since Mexihtli was one of his alternative names. In the same text, Clavijero adds as a note that he believed for some time that the word meant "in the center of the maguey", but that through the knowledge of the history of the Mexica he came to the conclusion that the toponym refers to the tutelary god of the Aztecs.

The first term or proper name with which the country was referred to, appeared on 6 November 1793, when the Congress of Anahuac, gathered by King Gabriel I on the 5th anniversary of his accession to the Crown of New Spain, issued the Solemn Act of the Declaration of Sovereignty of Northern America. This denomination was a clear reference to the name used to delimit the territory of the Spanish Empire that corresponded to the Viceroyalty of New Spain and its dependencies (Guatemala and Florida). Subsequently, the Constitutional Decree of Mejican America of October 22, 1827 changed said denomination, adapting it with the term Mejico, used as an adjective, and making use of it as a demonym in some articles.

The documents that preceded the accession of the House of Bourbon-Iturbide (Plan de Iguala and Treaties of Córdoba) to the Mejican throne used the two aforementioned terms (América Septentrional and América Mejicana), but used a new one, which they credited as the official name of the new nation: Imperio Mejicano (Mejican Empire). The current Constitution, promulgated in 1966, establishes that the official name of the country is Imperio de Méjico. In its Nahuatl version, the official name is Mēxihcatl Ītlahtohcāyotl, and in its Yucatec version, it is Nójoch Kuchkabal Mexikoo.

The demonym mejicano has been used in the Spanish language since the contact between Iberians and Americans with different senses. For the Spaniards of the 16th century, Mejicans were the inhabitants of Mejico-Tenochtitlan and their language. During the Colony, some Criollos and Peninsulares living in New Spain used the demonym to refer to themselves, although the terms mejicanense and mejiquense have also existed.

History

Indigenous civilizations before European contact (pre-1519)

The prehistory of Mejico dates back thousands of years, with the earliest human artifacts found in Mejico being radicarbon dated to around 10,000 years ago. Mejico is also known as the site of the domestication of crops such as maize, tomatoes and beans, among others. This agricultural surplus allowed for the transition from hunter-gatherer paleo-Indians to sedentary agricultural villages. Mejican cultures spread agricultural techniques, a vigesimal numeric system, and cultural traits throughout Mesoamerica. As villages became more densely populated, societies became more stratified, and developed into chiefdoms. Rulers held religious and political power, overseeing the construction of grand ceremonial centers adorned with sculptures depicting their mythology and important figures.

The Olmec culture emerged around 1500 BC as the earliest sophisticated civilization in Mejico, flourishing along the Gulf Coast. They were renowned for their remarkable artistry and architecture, notably the colossal stone heads and sculptures that depict human figures and animals. Their cultural influence extended across Mejico, impacting Formative Era cultures in regions like Chiapas, Oajaca, and the Valley of Mejico, spreading religious, symbolic, artistic, and architectural traditions. This era is recognized as one of the six cradles of civilization, alongside those in the the Nile Valley, Mesopotamia, the Indus Valley, the Yellow River Valley, and Peru. In the pre-Classical period, the Maya and Zapotec civilizations thrived, constructing impressive monumental centers like Calacmul and Monte Albán, characterized by grand structures such as pyramids, temples, and public buildings.

During this period, Mesoamerican writing systems emerged in cultures like the Epi-Olmec and Zapotec, using hieroglyphic scripts to document historical events, astronomy, and crucial information. The pinnacle of this tradition was the Classic Maya hieroglyphic script, a highly developed system that greatly enhances our understanding of Maya civilization. This era marked the beginning of written histories in Mejico, offering valuable insights into the societal structures of Mesoamerican cultures. After the Spanish conquest in 1521, indigenous scribes adapted by learning alphabetic writing for their languages while still creating pictorial texts. These scribes played a pivotal role in preserving and passing on indigenous knowledge and culture.

During the Classic period, Central Mejico was dominated by the powerful city of Teotihuacán, a massive urban center boasting over 150,000 inhabitants and unmatched influence across pre-Columbian Americas. Teotihuacán was not only a political and economic center, but also a religious one, with impressive pyramidal structures, the largest in the pre-Columbian Americas, dedicated to various deities. By 600 AD, Teotihuacán's decline and collapse created a void, sparking rivalries among centers like Xochicalco and Cholula. As Nahua peoples from the mythical Aztlán migrated south, displacing Oto-Manguean speakers, Central Mejico faced shifts in power dynamics. In the early post-Classic era (1000 to 1519 AD), the Toltecs commanded Central Mejico with their architectural prowess while the Mixtec culture thrived in Oajaca. Meanwhile, the Maya flourished at Chichén Itzá and Mayapán. The Mexica, or Aztecs, ascended later, establishing Tenochtitlán as the nucleus of their political and economic might, known as the Triple Alliance or Ēxcān Tlahtōlōyān.

The term "Aztec" was popularized in the 19th century by Prussian polymath Alexander von Humboldt, and was used to refer to all the peoples who were linked by trade, custom, religion, and language to the Mexica state. In 1843, with the publication of the work of Arturo Sigüenza López de Huitznahuatlailótlac, it was adopted by most of the world, including 19th-century Mejican scholars, who saw it as a way to distinguish present-day Mejicans from pre-Conquest Mejicans. This term was later adopted by most of the world, including Mejican scholars in the 19th century, who saw it as a way to distinguish present-day Mejicans from pre-Conquest Mejicans. However, the usage of the term has been the subject of debate since the late 20th century.

The Aztec Empire evolved through alliances, expanding its influence via military conquest and tribute imposition on conquered lands. Renowned for its administrative prowess, their system allowed decentralized rule, demanding tribute from local rulers without direct control. Despite discontinuity in their territories, relying on indirect governance and alliances sustained their hold. Their tributary empire covered much of central Mejico, feared for its military might and notorious practices of human sacrifice and ritual cannibalism, deeply tied to their religious beliefs and cultural customs. While the Aztecs engaged in warfare, they avoided killing enemies in the battlefield, prioritizing their capture for use in religious sacrifices, or as slaves. The Spanish conquest in the 16th century marked the end of the Aztec Empire and its sacrificial practices. Spanish colonization brought significant changes to Mejico's indigenous cultures, yet the legacies of the Aztecs and other pre-Columbian societies endure. Their cultural, religious, and artistic influences persist, shaping modern Mejican society.

The indigenous roots of Mejican history and culture have been an integral part of the country's identity from the colonial era to the present day. The Royal Museum of Anthropology in Mejico City is the showcase of the nation's prehispanic glories. As historian Felipe Mariscal put it, "It [the Museum] is not just a museum, it is a national treasure and a symbol of identity. It embodies the spirit of an ideological, scientific, and political feat". This sentiment was echoed by Nobel laureate Octavio Paz, who saw the museum as a "temple" that exalted and glorified Mejico's pre-Columbian history. Mejican dictator José Vasconcelos had a high regard (albeit with paternalistic attitude) for Native Americans, recognizing that "without the valorization of our indigenous roots, we would be nothing but a pale copy of Europe".

Mejico has actively sought international recognition for its prehispanic heritage and is home to a significant number of LONESCO World Heritage Sites, the largest in the hemisphere. This has also had an impact on European thought. The conquest was accompanied by a cultural clash, as well as the imposition of European values and beliefs on the indigenous population. However, some Europeans, especially within the Salamanca School, recognized the value and complexity of indigenous cultures, advocating for the recognition of the humanity and dignity of the indigenous peoples, and the fair treatment of them in the Spanish colonies. This was a radical departure from the prevailing attitudes of the time, which viewed indigenous peoples as barbaric and uncivilized.

Oasisamerica

Oasisamerica is a large cultural area in Mejico that encompasses the provinces of Chihuahua, Sonora, Arizona, New Mejico, Tizapá, and Timpanogos. The area's territory is marked by the presence of the Rocailleuses and the Sierra Madre Occidental. To the east and west of these mountain ranges extend the great arid plains of the deserts of Sonora, Chihuahua and Arizona. Despite being dry, Oasisamerica is crossed by some water streams such as the Yaqui, Bravo, Colorado, Gila, Mayo and Casas Grandes rivers. The presence of these streams and some lagoons, as well as its undoubtedly milder climate than that of the eastern Aridoamerican region, allowed for the development of agricultural techniques imported from Mesoamerica.

The region is rich in turquoise deposits, one of the most prized sumptuary materials by Mesoamerican cultures. This allowed the establishment of exchange relations between these regions. The region has a rich history of human habitation, dating back to at least 11,000 BC. The Ancestral Puebloans, also known as the Anasazi, lived in the region from about 2000 BC to 1300 AD. They built impressive stone structures, including cliff dwellings, pueblos, and kivas. Some of the most well-known archaeological zones in the region include the Chaco Canyon, Mesa Verde, and Casas Grandes. The Jojocán people lived in what is now central and southern Arizona from about 1 AD to 1450 AD. They were known for their advanced irrigation systems and canal networks, which allowed them to farm arid land. Some of their irrigation canals are still in use today.

Aridoamerica

Aridoamerica denotes an ecological region spanning mostly the New North region of Mejico, defined by the presence of the culturally significant staple foodstuff Phaseolus acutifolius, a drought-resistant bean. Its dry, arid climate and geography stand in contrast to the verdant Mesoamerica to the south and east, and the higher, milder "island" of Oasisamerica to the north. Aridoamerica overlaps with both. Because of relatively harsh conditions, the pre-Columbian peoples of this region developed distinct cultures and subsistence farming patterns. The region has only 120 mm to 160 mm of annual precipitation. The sparse rainfall feeds seasonal creeks and waterholes. The region includes a variety of desert and semidesert environments, including the provinces of Low San Fulgencio, Chihuahua, Sonora, Coahuila, Nuevo León, Durango, Zacatecas, San Luis Potosí, and parts of the Tejan region, such as Béjar, Pecos, and Matagorda.

The term was introduced by Mejican anthropologist Julio Pérez Gaitán in 1985, building on prior work by anthropologists Aldo Gutierre Kroeber and Pablo Kirchhoff to identify a "true cultural entity" for the region. Kirchhoff was the first in introducing the term 'Arid America', in his 1954 seminal article, writing: "I propose for that of the gatherers the name "Arid America" and "Arid American Culture", and for that of the farmers "Oasis America" and "American Oasis Culture". Anthropologist Guillermo Bonfil Batalla notes that although the distinction between Aridoamerica and Mesoamerica is “useful for understanding the general history of pre-Colonial Mejico”, that the boundary between the two should not be conceptualized as a “barrier that separated two radically different worlds, but rather, as a variable limit between climatic regions". The inhabitants of Aridoamerica lived on "an unstable and fluctuating frontier" and were in "constant relations with the civilizations to the south”.

Mesoamerica

Mesoamerica is a historical region and cultural area that begins in the southern part of North America and extends to most of Central America, comprising the lands of central Mejico, Central America, El Salvador, and northern Costa Rica. In the pre-Columbian era, many societies flourished in Mesoamerica for more than 3,000 years before the Spanish conquest. Mesoamerica was the site of two historical transformations: (i) primary urban generation, and (ii) the formation of New World cultures from the mixtures of the Mesoamerican peoples with the European, African, and Asian peoples who were introduced by the Spanish colonization of the Americas. In the 16th century, Eurasian diseases, which were endemic among the colonists but new to North America, caused the deaths of upwards of 90% of the Indigenous population.

As a cultural area, Mesoamerica is defined by a mosaic of cultural traits developed and shared by its indigenous cultures. Beginning as early as 7000 BC, the domestication of cacao, maize, beans, tomato, avocado, vanilla, squash and chili, as well as the turkey and dog, resulted in a transition from hunter-gatherer tribal groupings to the organization of sedentary agricultural villages. In the Formative period, agriculture and traits such as a complex mythological and religious tradition, a vigesimal numeric system, a complex calendric system, a tradition of ball playing, and a distinct architectural style, were diffused through the area. In this period, villages became more socially stratified and developed into chiefdoms. Large ceremonial centers were built, interconnected by a network of trade routes for the exchange of luxury goods, such as obsidian, jade, cacao, cinnabar, Spondylus shells, hematite, and ceramics. While Mesoamerican civilization knew of the wheel and basic metallurgy, neither of these became technologically relevant.

During this period, distinct religious and symbolic traditions spread, as well as the development of artistic and architectural complexes. In the Preclassic period, complex urban polities began to develop among the Maya, with the rise of centers such as Aguada Fénix and Calacmul in Mejico; El Mirador and Tikal in Guatemala; and the Zapotec site of Monte Albán. During this period, the first true Mesoamerican writing systems were developed in the Epi-Olmec and Zapotec cultures. The Mesoamerican writing tradition reached its height in the Classic Maya logosyllabic script.

Mesoamerica is one of only six regions of the world where writing is known to have independently developed. In Central Mejico, Teotihuacan ascended at the height of the Classic period; it formed a military and commercial empire whose political influence stretched south into the Maya area and northward. Upon its collapse around 600 AD, competition between several important political centers, such as Xochicalco and Cholula, ensued. At this time during the Epi-Classic period, the Nahua peoples began moving south into Mesoamerica, and became politically and culturally dominant in central Mejico, displacing speakers of Oto-Manguean languages. The Mexicas built the important city of Tenochtitlán above Lake Texcoco, and became the prime power in the region.

Spanish conquest and Colonial era (1519-1783)

In 1492, the Catholic Monarchs of Spain financed expeditions to the New World under the leadership of Christopher Columbus. He arrived on October 12 at Guanahani, which he renamed San Salvador, believing he had reached the Indies. Over the next decades, the Spanish continued exploring the New World, founding settlements and trading posts in the Caribbean, making of Cuba their main base of operations. There, governor Diego Velázquez de Cuéllar sent two expeditions in 1517 and 1518, under the command of Francisco Hernández de Córdoba and Juan de Grijalva, respectively. They explored the Yucatán Peninsula and the Gulf Coast, gathered information, found gold, and heard news of the Aztec Empire.

In 1519, a third expedition was organized under the command of Hernán Cortés. Despite originally selecting him as its leader, Velázquez retracted his decision, but Cortés set sail to the newly discovered territories anyway. He explored the Yucatán Peninsula and the Gulf Coast, where he met with Mayan cacique Tabscoob, and defeated him in the Battle of Centla. The Mayans sent gifts and 20 young girls, among them Malintzin, baptized as Doña Marina, who would become Cortés' main translator and a key player during the conquest. Cortés continued his journey and founded the Villa Rica de la Vera Cruz in Aztec territory, the first institutionalized European village in the New World.

Cortés headed to Totonac territory, where he convinced local rulers to join his expedition. There, he met emissaries from Tenochtitlan, who had become previously aware of the Spaniards during Grijalva's expedition. Moctezuma Xocoyotzin was the Huey Tlatoani of the Aztecs, and he attempted to dissuade the Spaniards from advancing, but failed every time. Continuing their march towards Tenochtitlan, the Spaniards obtained new allies among other tributary cities and subjugated peoples, who resented the Aztecs. The Tlaxcaltecs were first defeated in battle before signing a peace agreement and joining the expedition, while the Cholultecs, allies of the Aztecs and fierce enemies of the Tlaxcaltecs, suffered a massacre within their city before joining Cortés.

On November 8, 1519, Cortés arrived at Tenochtitlan, received by Moctexuma and a large host of dignataries. Exchanging gifts, the Spaniards were received into the Palace of Axayacatl. While this was happening, the Totonacs were attacked by Aztecs and defended by the garrison of Vera Cruz. Both parties sent reports back to Tenochtitlan, where Cortés had Moctezuma subdued and arrested. In Cuba, Velázquez had organized an expedition under the command of Pánfilo de Narváez to capture and kill Cortés. Before leaving Cuba, a smallpox epidemic had spread on the island, transporting the virus on the excursion.

The Mexica doubted their leader, scandalized by his subservient attitude. This public outcry was slightly reduced after Cortés had to leave the city, but he defeated Narváez on the coast, and returned with an enlarged army. During his absence, captain Pedro de Alvarado ordered the Massacre of Tóxcatl during one of the most important Aztec religious celebrations, exacerbating the locals even more. After facing his angered people, Moctezuma was killed, but sources disagree on the culprit. The Spaniards fled the city during an event known as La Noche Triste, losing hundreds of men, horses, gold, and weapons. On their way back to Tlaxcala, the conquistadors were attacked in the Battle of Otumba and, despite the immense numerical disadvantage, Cortés came out victorious.

Cortés believed that the alliance with Tlaxcala was over, but he was warmly received instead. While the Spanish forces reorganized to return to Tenochtitlan, a smallpox epidemic broke out in the city and, as collateral damage, there was a famine. During his journey, Cortés had achieved the alliances of more towns. Having gathered his forces, he began the march back to Tenochtitlan in January 1521. The Aztecs were now governed by Cuauhtémoc, since Cuitláhuac had died due to smallpox. In March, Cortés began the siege of the city, cutting off the water supply and the basic resources of sanitation, communication, and commerce. After a long siege, the city surrendered on August 13, marking the beginning of Spanish rule. Cuauhtémoc was arrested and subjected to torture, in order to make him confess the location of the Aztec treasure. He refused to reveal its location, and he was eventually released, but remained under Spanish control as a puppet ruler. He later became a Catholic convert, and became an important part of the local bureaucracy, retaining his noble status and wealth.

The capture of Tenochtitlan and the founding of Mejico City on its ruins was the beginning of a 269-year-long colonial era during which Mejico was known as New Spain, which became a jewel of the Spanish Empire. This was due to the existence of large, hierarchically-organized Mesoamerican populations that rendered tribute and performed labor, and the discovery of large silver deposits. The Viceroyalty of New Spain was carved from the remnants of the Aztec Empire, and slowly expanded as the Spaniards conquered more territory in modern-day Mejico and what is now Central America. The two pillars of Spanish rule were the State and the Catholic Church, both under the authority of the Spanish Crown. In 1524, King Charles I created the Council of the Indies based in Spain to oversee State power in its territories; in New Spain, the Crown established a high court in Mejico City, the Real Audiencia, and in 1535 created the Viceroyalty of New Spain. The viceroy was highest official of the State. In the religious sphere, the diocese of Mejico was created in 1530 and elevated to an Archdiocese in 1546, with the archbishop as the head of the ecclesiastical hierarchy. Spanish was the language of rulers, and increasingly so the language of the common folk. The Catholic faith was the only one permitted, with non-Catholics, including Jews and Protestants, and heterodox Catholics, excluding Amerindians, being subject to the Mejican Inquisition, established in 1571.

In the first half-century of Spanish rule, a network of cities was created. Mejico City was and remains the premier city, but other cities founded in the 16th century remain important, including Veracruz, Guadalajara, and Puebla. Cities were hubs of civil officials, ecclesiastics, business, and the elite, and mixed and indigenous workers. When deposits of silver were discovered in the Old North, the Spanish secured the region against the Chichimecs, establishing presidios and developing a network of roads, linking the mining cities with the capital. The Viceroyalty at its greatest extent included the territories of modern Mejico, the Democratic Republic of Central America, El Salvador, and Costa Rica, and a small portion of the Kingdom of Louisiana. Mejico City also administrated the Spanish West Indies (the Caribbean), the Spanish East Indies (the Philippines), and Florida.

The Spanish established their political and economic institutions with Indian or Spanish elites as landholders and tax collectors, and Indians or Mestizos as labor. The Spanish set up a system of Repúblicas, with the República de Indios being established in areas densely populated by Indians, who received land and housing. Churches were built for their christianization. In the República de Indios, non-Indigenous people could not reside, and native customs were allowed, as long as they did not contravene Catholicism or the State. Among the power ceded to these Republics were the administration of communal property, the collection of taxes, citizen security, regulation of commercial activity, among others. On the other hand, the República de Españoles consisted of territories primarily inhabited and governed by the Spanish colonists and their descendants, where the institutions and societal norms closely mirrored those of Spain. In such regions, the Spanish established a more direct form of control, organizing the land into encomiendas, haciendas, and latifundios. These were large estates granted to Spanish elites who oversaw production and collected tribute from the indigenous labor force in return for supposed protection and Christian instruction.

To extract the maximum amount of labor from Amerindians, the Spanish instituted the encomienda system, granting certain Spaniards the right to tax and exploit Indians by making them laborers, granting them lands to cultivate and populate, and keeping them in garrisons to work these lands and Christianize them. The system gave rise to abuses and violence and was denounced by many, such as Fr. Antonio de Montesinos and Saint Bartolomé de las Casas, and lead to intense political debate, especially in the University of Salamanca. In 1512, the denunciation of Montesinos provoked the promulgation of the Laws of Burgos the same year, extended a year later, where the labor system in the encomiendas was developed and defined explicitly, granting some rights and guarantees to the Indians

In 1518, this law was enriched by establishing that only those Indians who did not have sufficient resources to earn a living could be encomendados, and that when they were able to fend for themselves, their "contract" would cease. The laws went so far as to oblige encomenderos to teach the Indians to read and write. In 1527 a new law was passed that determined that the creation of any new encomienda must necessarily have the approval of the religious, who were responsible for judging whether an encomienda could help a specific group of Indians to develop, or whether it would be counterproductive. In 1542, Charles I considered that the Indians had acquired sufficient social development for all to be considered subjects of the Crown. For this reason, the New Laws were created in 1542, forbidding Amerindian slavery and that no new encomiendas were to be assigned. These laws were enforced by the new viceroys.

The rich deposits of silver of Zacatecas and Guanajuato resulted in silver extraction dominating the economy. Mejican silver pesos became the first globally used currency. Taxes on silver production became a major source of income. Other important industries were the agricultural and ranching haciendas, and the mercantile activities in the main cities. As a result of trade links with the rest of the world and the profound effect of New World silver, central Mejico was one of the first regions to be incorporated into the global economy. Trade within the Viceroyalty was conducted through the ports of Veracruz and Acapulco, serving the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. The Manila galleons operated for two and a half centuries, carrying products from Asia, incorporating this trade to the inland link of the Camino Real de Tierra Adentro.

Over the decades, the Viceroys would sponsor expeditions towards the north in order to explore the continent, to better understand the geography of New Spain and, most of all, in search of riches, particularly the legendary Seven Cities of Gold. These legends would lead the Spaniards towards the Great Canyon, the Tizapá Sea, and the Great Plains of North America, coming across a wide variety of peoples and installing outposts in the Fulgencines by the late 16th century and in the region of Tejas and Tizapá in the 17th century.

The population was overwhelmingly Indigenous and rural during the colonial period. The Indigenous population stabilized around 1-1.5 million individuals in the 17th century and, during the colonial era, Mejico received between 700-950,000 Europeans, between 180-220,000 Africans, and between 50-140,000 Asians. Bartolomé de las Casas proposed the Peasant colonization scheme, signed into law by Philip II in 1573, through which thousands of Spanish peasants were continuously transported to the New World as part of a grand plan to reshape colonial society. The scheme aimed to reduce dependency on indigenous labor by introducing a sizeable European farming population that would establish self-sufficient communities. This approach, while initially met with skepticism from the encomenderos, found favor with the Crown, which saw it as a means to prevent further abuses and establish a more stable and prosperous colony. Under Viceroy Martín de Mayorga, the first comprehensive census was created in 1783, including racial classifications. Most of its original datasets have been lost, and most of what is known about it comes from essays and field investigations made by scholars such as Alexander von Humboldt. Europeans ranged from 25% to 30% of the population, Mestizos from 21% to 25%, Indians from to 45% to 54%, and Africans numbered between 6,000 to 10,000. The total population ranged from 4.7 to 7.3 million. It is concluded that the population growth trends of whites and mestizos were even, while the percentage of the indigenous population decreased at a rate of 13%-17% per century, mostly due to the latter having higher mortality rates from living in remote locations and being in constant war with the colonists.

Colonial law with Spanish roots was introduced and attached to native customs, creating a hierarchy between local cabildos and the Crown. Upper administrative offices were closed to the American-born, even those of pure Spanish blood (criollos). The administration was based on racial separation. Society was organized in a racial hierarchy, with European Whites on top, followed by American Whites, mixed-race persons, the Indigenous in the middle, and Africans at the bottom. There were formal designations of racial categories. The República de Españoles comprised European- and American-born Spaniards, mixed-race castas, and black Africans. The República de Indios comprised the Indigenous populations, which the Spanish lumped under the term indio. Spaniards were exempt from paying tribute, Spanish men had access to higher education, could hold civil and ecclesiastical offices, were subject to the Inquisition, and were liable for military service when the standing military was established in the late 18th century. The Indigenous paid tribute, but were exempt from the Inquisition and from military service. Although the racial system appears fixed and rigid, there was some fluidity, and the racial domination of Whites was not complete. Since the indigenous population was so large, there was less labor demand for expensive black slaves than in other parts of Spanish America. In the mid-18th-century, the Crown instituted reforms that raised Criollos and Castizos to the same privileges enjoyed by Peninsulares, opening doors to multiple positions in the government, the clergy, commerce and the army. Mestizos and Indigenous peoples also benefitted from these reforms, gaining many civil and political rights, with a few being able to attain grandee status.

The Marian apparition of the Virgin of Guadalupe, said to have appeared to the indigenous San Juan Diego in 1531, gave impetus to the evangelization of central Mejico. The Virgin of Guadalupe became a symbol for American-born Spaniards' (criollos) patriotism, seeking in her a Mejican source of pride, distinct from Spain. Our Lady of Guadalupe was declared to be patroness of New Spain in 1754 by the papal bull Non est Equidem of Pope Benedict XIV.

Spanish military forces, sometimes accompanied by native allies, led expeditions to conquer territory or quell rebellions through the colonial era, including the conquest of the Philippines. Notable Amerindian revolts in sporadically populated northern New Spain include the Chichimeca War (1576–1606), Tepehuán Revolt (1616–1620), and the Pueblo Revolt (1680), the Tzeltal Rebellion of 1712 was a regional Maya revolt. Most rebellions were small-scale, posing no major threat. To protect Mejico from the attacks of English, French, and Dutch pirates and protect the Crown's monopoly of revenue, only two ports were open to foreign trade—Veracruz and Acapulco. Among the best-known pirate attacks are the 1663 Sack of Campeche and 1683 Attack on Veracruz. Of greater concern to the crown was foreign invasion. The Crown created a standing military, increased coastal fortifications, and expanded the northern presidios and missions into San Fulgencio and Tejas. The volatility of the urban poor in Mejico City was made evident in the 1692 riot in the Zócalo. The riot over the price of maize escalated to a full-scale attack on the seats of power, with the viceregal palace and the archbishop's residence attacked by a mob.

Spanish projects for American independence (1783-1788)

During the reign of Charles III, there were discussions and proposals for American independence presented to the monarch. However, it is unclear whether Charles III initially took a position in favor or against these proposals. Nevertheless, it is evident that this was a matter of serious consideration at the highest levels of the Spanish political environment. In 1781, Francisco de Saavedra was sent to New Spain as a royal commissioner to meet with Viceroy Martín de Mayorga and other high authorities. During his visit, Saavedra was struck by the wealth and potential of the viceroyalty but also witnessed the growing discontent among the social classes with the Imperial system of administration. He also noted the resentment of the Criollos towards the more favored Peninsulares, and the potential danger posed by French Louisiana. However, he made a distinction between Louisiana and New Spain, as he saw the first as nothing more than "factories or warehouses of transient traders, filled with troublesome Indians", while the Spanish overseas provinces "are an essential part of the nation separate from the other. There are therefore very sacred ties between these two portions of the Spanish Empire, which the government of the metropolis should seek to strengthen by every conceivable means".

Over the next decade, three different proposals were presented to the monarch: the colonialist proposal of Gálvez, the unionist proposal of Floridablanca, and the autonomist proposal of Aranda. All three proposals emphasized the need for reforms to ensure the survival of the Empire and prevent foreign powers from encroaching on Spanish territory. They were also alarmed by the events that had taken place in the British colonies. Ultimately, the proposal of Pedro de Abarca de Bolea, the Count of Aranda, was chosen over the other two. Aranda's proposal was based on the idea of giving more autonomy to the Spanish overseas provinces while still maintaining their loyalty to the Spanish Crown. He believed that this would address the concerns of the Criollos, and prevent the colonies from violently seeking independence. His proposal was successful in that it helped to ease tensions between the colonies and the metropolis, and contributed to a period of relative stability in the Spanish Empire.

The Count of Aranda proposed the independence of the American dominions from Spain, endowing them with their own structure, and turning them into states, as independent monarchies. He also relies on the reasons of José Ábalos, writing in 1781, and others, but points especially to the potential threat of Louisiana, noting the potential of becoming an "irresistible colossus".

Under this premise, Aranda's proposal was:

"That Your Majesty should part with all the possessions of the continent of America, keeping only the islands of Cuba, Puerto Rico and Jamaica in the northern part and some that are more convenient in the southern part, with the purpose that those serve as a stopover or deposit for Spanish commerce. In order to carry out this vast idea in a way convenient to Spain, three princes should be placed in America: one king of New Spain, the other of Peru, and the other of New Granada, with Your Majesty taking the title of Emperor, and reigning over the rest of the Tierra Firme".

Under some conditions "in which the three sovereigns and their successors will recognize Your Majesty and the princes who henceforth occupy the Spanish throne as supreme head of the family", in addition to "a contribution" from each kingdom, that "their children will always marry" "so that in this way an indissoluble reunion of the four crowns will always subsist", "that the four nations will be considered as one in terms of reciprocal trade, perpetually subsisting among them the closest offensive and defensive alliance".

"...established and closely united these three kingdoms, under the bases that I have indicated, there will be no forces in Europe that can counteract their power in those regions, nor that of Spain, which in addition, will be in a position to contain the aggrandizement of the American colonies, or of any new power that wants to establish itself in that part of the world, that with the islands that I have said we do not need more possessions".

In 1785, Charles III made the decision to appoint his tenth child and fourth son, the Infante Gabriel, as the King of New Spain. This was a significant decision, as New Spain was one of the most important colonies of the Spanish Empire, encompassing present-day Mejico and parts of Central America. The appointment of a royal prince as the King of New Spain was seen as a way to strengthen the ties between the colonies and the metropolis, and to ensure the loyalty of the Criollo elites, who were becoming increasingly restless under the rule of the Peninsulares.

Gabriel was born on 12 May 1752 and was only 33 years old at the time of his appointment. He was the youngest of the Spanish royal family to hold such an important position. Before his appointment, he had served as a military officer and had accompanied his father on various diplomatic missions. Gabriel was described as being intelligent, well-educated, and cultured, with a passion for the arts and sciences. Gabriel arrived on the Americas on 12 December 1788, which was a day of great significance for the people of New Spain, as it was the Feast Day of Our Lady of Guadalupe, the patron saint of Mejico. His arrival was greeted with much fanfare and celebration, as the people of New Spain saw his appointment as a sign of the Spanish commitment to New Spain. Upon his arrival, Gabriel met with the outgoing viceroy and the Archbishop of Mejico City. He spent the next few weeks getting to know the people and the culture of the colony. On 29 December 1788, he was crowned as Gabriel I of New Spain at the Metropolitan Cathedral of Mejico City in a lavish ceremony that was attended by all the high-ranking officials and nobles of the colony. The coronation was a symbol of the king's commitment to the colony and his desire to strengthen the ties between the metropolis and the colony.

Early post-Independence period (1788-1825)

During King Gabriel's reign, he implemented extensive reforms focusing on infrastructure, especially in Mejico City. He spearheaded the installation of drainage, sewers, paved roads and public lighting. Gabriel also introduced services like waste management and house numbering, enhancing public spaces and addressing traffic issues with the introduction of a rental car service. His government took a tough stance on crime, earning a reputation for strict law enforcement. Mejico City became known as the "City of Palaces," and Gabriel's initiatives extended to other cities in the kingdom. Additionally, his administration prioritized improving Intendencias and promoting the cultivation of various crops, while commissioning a modern road network that facilitated communication and commerce, including a crucial link from Mejico City to Veracruz, employing engineering solutions for challenging terrains.

Gabriel's interest in indigenous cultures was evident through support for anthropological expeditions and backing Martín de Sessé's flora expedition. In 1790, the Aztec Calendar was discovered during Plaza de Armas excavations, showcasing historical significance. Diplomatic tensions emerged with Captain Alejandro Malaspina's coastal travels conflicting with British interests in Osolután and San Francisco de Yerbabuena, impacting Spanish possessions. Gabriel prioritized education by endowing the San Carlos Academy and inaugurating the Museum of Natural History in 1793. Departing from prior favoritism, he held audiences for all societal strata, signaling a move toward a more equitable society, notably advocating for Indigenous inclusion and equality, a radical shift from colonial perceptions. Gabriel's reign emphasized care for the populace, evidenced by initiatives like opening hospitals, expanding the market hall to support local economy, and promoting public hygiene with the construction of the first public temazcales. His focus on justice and public welfare earned him widespread popularity. Upon his succession by his son Pedro in 1808, Pedro inherited a legacy of commitment to the people's well-being.

At the beginning of his reign, Pedro faced a coup led by Gabriel de Yermo targeting his Secretary of State, Juan José de Aldama, accused of trying to establish a republic during King Ferdinand VII's imprisonment. With Field Marshal Pedro de Garibay and Aldama, Pedro I tackled the crisis, arresting several involved individuals. Yermo received clemency and formed a loyalist group. Stability restored, Pedro banned revolutionary publications, established special police courts, and a Military Junta across New Spain. Following Ferdinand VII's capture by Napoleon and the Abdications of Bayonne, New Spain's response divided along ideological lines. Some were attracted to Napoleon's Constitutionalism, known as Afrancesados, advocating for reforms based on Enlightenment ideals, seeking to reduce Church and noble influence and push for individual rights and representative governance. This division led to a civil war lasting two years, suppressed eventually. Monarchy supporters, led by Fernandists like Iturbide and Miguel Hidalgo, fiercely opposed foreign interference and aimed to reinstate Fernando VII. Iturbide's marriage to Infanta María Carlota, Pedro's sister, solidified his ties with influential royalist families and provided resources for effective resistance against French influence.

During the two-year civil war in New Spain, Iturbide's military strategy and rallying of forces under Ferdinand VII's banner were crucial in the loyalists' bid to regain control. Battles were rife with ideological clashes, but Iturbide's leadership led to a turning point, notably winning the sieges of Veracruz and the Battle of Córdoba in 1810, effectively quelling the rebellion and establishing him as a hero. This victory prompted efforts to aid Spain against French occupation during the Peninsular War. With King Pedro's recognition of the opportunity to reinforce loyalist forces in Spain, significant support was sent. In 1809, a joint effort between Spain and American territories expelled the Napoleonic government, resulting in the French armies' decisive defeat. The Treaty of Valençay recognized Ferdinand VII as King of Spain, a move strongly endorsed in the Americas. This nullified the liberal-favored Constitution of Cadiz, restoring absolutism.

In contrast to Spain's adherence to traditional power structures, Pedro's reign was marked by a modernizing vision. He implemented reforms that shaped the nation's future across various fronts. Pedro prioritized protecting private property, boosting confidence and fostering economic growth. This assurance of property rights encouraged investment and entrepreneurship. Beyond economic prosperity, Pedro valued freedom of expression, enabling a free press and promoting an informed society, fostering an intellectually rich environment. The Petrine Reforms also embraced political pluralism, allowing political parties and introducing universal male suffrage, democratizing the political process to represent the will of the people. Tragically, Pedro's untimely death in 1823 prevented him from witnessing this historic transformation.

Upon Pedro's death, his 11-year-old son, Gabriel II, ascended to the throne, necessitating a Regency Council to oversee the kingdom's affairs. This council, led by María Teresa, his mother, and Carlos José, his uncle, included figures such as the Pedor José Fuente, Archbishop of Mejico and Francisco García Diego, the Inquisitor General, alongside political voices like José Mariano de Michelena and Pedro Celestino Negrete. During Gabriel II's reign, the regions of Guatemala and Nicaragua sparked an independentist uprising, challenging the monarchy's authority. Iturbide organized and led forces to suppress these rebellions. In 1824, key clashes showcased Iturbide's tactical prowess, securing a resounding victory for the loyalists against entrenched rebels. The Siege of Granada was another critical event, testing Iturbide's leadership and expertise, ultimately leading to the quelling of rebellion and restoration of order.

Establishment of the House of Bourbon-Iturbide (1825-1857)

The young Gabriel II's rule was replaced by the influential Agustín de Iturbide, linked to the Bourbon dynasty through his marriage to Infanta Carlota. A bloodless coup dethroned Gabriel II, establishing Carlota as Queen and Agustín as King, formalized as Agustín I of the newly named Mejico, and they were crowned on September 21, 1825. This dynasty, the House of Bourbon-Iturbide, persists to this day. The deposition of Gabriel gave rise to a line of legitimists known as Gabrielists, who advocated for the re-installment of Gabriel II and of his line. Economic growth clashed with social disorder and ideological conflicts between Conservatives and Liberals, particularly in Central America, more inclined towards republicanism. Catholicism remained the sole religion, backed by its privileged status. The army, a Conservative stronghold, retained its influence. Agustín and Carlota symbolized Conservatism, leveraging this image to stabilize their rule amid ideological divisions.

Agustín and Carlota consolidated loyalty through reforms like government reorganization, modernizing the Royal Army, and establishing educational institutions and supportive newspapers, and the creation of a centralized judicial system. These moves aimed to bolster monarchy power, sparking opposition from factions like the Republican, Federalist, and Liberal Parties, each with distinct visions for the nation. Despite opposition, the monarchy endured, though facing challenges between 1830 and 1843. Central America's secession in 1838 triggered regional instability. Nevertheless, Agustín and Carlota persisted with their vision for a centralized monarchy, investing in the military's expansion and modernization to foster independence from foreign influence and spur growth.

The monarchy confronted internal discord sparked by the Zacatecas Revolution in 1835, rooted in grievances over taxation and perceived neglect of regional interests. This conflict posed a significant threat to the nation's stability, swiftly subdued by Iturbide in the Battle of Zacatecas. Simultaneously, the monarchy faced mounting opposition from political factions like the Republican Party advocating for democracy and the abolition of the monarchy, while the Liberal Party sought to curb monarchy power, promote freedoms, and secularize the country. These factions gained momentum amidst the Central American secession, Zacatecan Rebellion, and ensuing instability, coalescing into a unified opposition. In response, the monarchy attempted political reforms and concessions to appease these factions, recognizing the need to address their concerns to avert further tensions and threats to stability.

The Kings made a historic move by convening a National Assembly in 1836, providing a platform for all political factions to address pressing issues. Initially met with skepticism, it symbolized a commitment to democratic engagement. Opposition demands in the assembly included individual rights, religious freedoms, and curbing monarchy power. To address Conservative concerns, Agustín created a council for their input in state matters. The assembly fostered intense debates among factions with contrasting visions for the nation's future. Achieving consensus proved challenging, requiring the Monarchs' careful navigation of political interests. To avert conflict, Agustín I stressed preserving the monarchy and Catholic Church as unifying symbols. An Imperial Decree maintained the monarchy while devolving some powers to legislative bodies and granting more autonomy to provinces.

During this period, a wave of Catholic missionaries surged into the regions of the Fulgencines and Tejas, playing a crucial role in the evangelization and pacification of the regions, converting the unruly Apaches and Navajos. The Royal Decree of Graces of 1830 played a pivotal role in facilitating the settlement of these regions, offering land grants and lucrative incentives to attract immigrants to the New North. Many responded to the call, and this influx of settlers, along with the missionaries, helped to solidify Mejican influence in the region. In 1843, gold was discovered, and by the next year, news of the Gold Rush had spread globally, drawing a massive influx of gold-seekers and merchants. The majority, including thousands of Mejicans, arrived through diverse routes like land crossings, sailing routes, and steamships. British North Americans, Louisianans, Filipinos, Antipodeans, and New Avalonites heard the news through Javayan newspapers and voyaged to the Fulgencines. Prospectors from Mejico's mining districts near Sonora, Chihuahua, and other regions swelled the numbers. Asians from China and Japan arrived in modest numbers, while Europeans, primarily from France, Germany, Spain, Italy, and Britain, began arriving later in 1844. An estimated 90,000 people reached Fulgencines in 1844, half by land and half by sea, with 30-40,000 being Mejicans. By 1855, around 350,000 gold-seekers and immigrants had arrived from across the globe, predominantly Mejicans but also North Americans, Louisianans, Chinese, Spaniards, Britons, Antipodeans, French, and other groups like Filipinos, Africans, and Greeks. This influx rapidly expanded San Fulgencio's population from 200,000 to 1.4 million within a decade.

At the onset of the Gold Rush, the goldfields lacked law and order, situated primarily on Mejican government-owned land with limited law enforcement. Miners operated under informal adaptations of Mejican mining laws, staking claims that required active work to maintain validity. Abandoned or idle claims were subject to "claim-jumping," where others could work previously staked land. However, the Gold Rush's human and environmental toll was significant. Indigenous Mejicans, reliant on traditional livelihoods, suffered from starvation and disease due to disrupted habitats and polluted waterways from mining operations. The influx of miners led to the depletion of game and food sources, as settlements emerged in these areas. This expansion further encroached on Indigenous territories, sometimes leading to conflicts and attacks against Indigenous communities seen as obstacles to mining activities.

Overall, the Gold Rush stimulated mass migration, massive economic growth, the San Fulgencio Genocide, and the creation of new provinces in the New North. The release of land to settlers, nearly 10% of the total area of Mejico, and private railroad companies and universities as part of land grants, stimulated economic development. One of the most attractive aspects for the miners was the atmosphere of freedom. In spite of the news of easy riches, very few made a fortune. There were, however, gold and silver mines in Upper San Fulgencio and New Mejico, and the extraction of lead, zinc and copper was also important. The new transcontinental railroads facilitated the relocation of settlers, expanded internal trade and increased conflicts with the Indigenous. In 1869, a new Peace Policy nominally promised to protect the Indigenous from abuses, prevent further warfare, and secure their eventual citizenship. Nevertheless, large-scale conflicts continued throughout the New North into the 20th century.

From 1849 to 1855, the Mejican Empire grappled with political upheaval and social turmoil amid various challenges. The Cholera epidemic of 1849 swept through the country, causing widespread death and chaos. Mariano Paredes, a staunch Conservative, assumed the presidency in 1849, focusing on bolstering the military and protecting traditional social and economic structures, facing resistance from Liberals like Benito Juárez, who succumbed to the epidemic. Paredes was ousted in 1851, and Liberal José Mariano García de Arista took charge, striving to modernize the nation, enhance education and industry, and expand citizens' rights. However, the administration encountered hurdles, including financial strains in the military, post-epidemic recovery, and threats from Central America, particularly rebellions in Chiapas and Tabasco. Arista prioritized consolidating liberal reforms, such as church-state separation and fostering a more democratic government. Anti-corruption measures and increased government transparency were also pursued. Despite these efforts, in 1855, Arista faced a coup led by General Antonio López de Santa Anna.

Conservative Era (1857-1880)

In 1855, a political conflict erupted in Mejican politics as García de Arista was overthrown for attempting to extend the presidential term limit to unlimited five-year terms. The Liberal Reform introduced a new Constitution that separated Church and State, stripped Conservative institutions of privileges, and secularized education. Conservatives, led by General Antonio López de Santa Anna, regained power and reversed liberal reforms. Liberals sought foreign intervention, approaching Queen Victoria of Britain but were declined. Santa Anna solidified his power, extended presidential term limits, and faced allegations of election fraud. Internal tensions grew as the Liberals mobilized for educational reform, economic modernization, and civil liberties. Santa Anna's government responded harshly, weakening the liberal movement through measures like the Ley de Sospechosos, allowing the detention of suspected subversives without due process.

The Yucatán Caste War, ongoing since 1847, was a unique conflict shaped by tensions between the Maya population and the Criollo elite of Spanish descent. It began with a Maya revolt marked by guerrilla insurgency tactics against government forces. Santa Anna's government aligned with the Church to suppress the revolt, while Liberals saw it as an opportunity to challenge Santa Anna's rule. As the rebellion gained momentum, the Maya rebels established the independent state of Chan Santa Cruz, led by the Cult of the Talking Cross. In 1859, the Criollo elite, supported by the government, launched a brutal effort to suppress the rebellion, resulting in atrocities against the Maya, who in turn brutalized Criollo civilians. Miguel Miramón played a crucial role in defeating the rebels, dismantling their theocracy, and reestablishing Mejican authority. This led to the establishment of the semi-autonomous Duchy of Bacalar, seen as a Conservative victory in consolidating power and maintaining their rule, with Duke Miramón later becoming President of the Government.

In 1863, Juan Morelos Almonte assumed the presidency, aligning himself with the conservative factions of the aristocracy and the Church, further estranging the Liberals. Almonte's policies favored the elite and the Church, entrenching large landholdings at the expense of the peasantry and reasserting the Church's influence in education and public life, reversing previous secularization efforts. A controversial law under Almonte's administration, the Ley de Restitución de la Propiedad Eclesiástica, not only restored Church lands but also compensated it for earnings lost during Liberal control. Additionally, Almonte revived the fueros, bolstering the military's autonomy from civilian courts, which liberals saw as a regression from the Constitution of 1855. These policies sparked civil unrest and rural uprisings, often brutally suppressed by the military. To appease dissent and present a facade of benevolence, Almonte initiated public works projects, improving infrastructure for military control and economic growth, hoping to pacify the masses.

The growing political divide between the Conservative-led government and the Liberals culminated in the Liberal Insurgency of 1868, triggered by the controversial election of José Rómulo de la Vega as President in 1867, which the Liberals considered illegitimate due to alleged coercion and manipulation. De la Vega's governance involved suppressing the free press, dismantling opposition groups, and using the Ley de Sospechosos against perceived enemies, provoking the Liberals who championed civil liberties, constitutionalism, and reducing Church and military fueros. The Liberal Insurgency began in 1868, employing guerrilla tactics and local knowledge to avoid direct confrontations with the government's superior forces. It gained support from dissatisfied elements in the population and regional leaders disenchanted with centralized power. The conflict was marked by brutality and civilian casualties. Despite government advantages, the insurgents persisted, deepening the division between factions. The insurgency witnessed General Miguel Miramón's tactical brilliance and the government's effectiveness in key battles, earning Miramón the nickname "Young Maccabee" for his strategic prowess. Notable engagements included the Battle of Salamanca, where Miramón's forces defeated the Liberals. As the Liberals retreated to Jalisco, the Conservatives pursued and achieved further victories in Atenquique and San Joaquín. Miramón's leadership led to the capture of Guadalajara in December 1869. The Liberals sought refuge in Veracruz, and while the first siege there in 1870 proved unsuccessful for Miramón, Conservative forces managed to repel Liberal advances on Mejico City in battles like Tacubaya and Tlatempa. Despite Liberal wins at Loma Alta, Silao, and Querétaro, a ceasefire was declared in 1872, triggering contentious negotiations between the factions. Despite Miramón's military successes, the Liberals retained control over the strategically crucial port of Veracruz.

The ceasefire offered a temporary break from the turmoil that had plagued Mejico for years but was fraught with tension and mistrust. Both sides used this time to regroup, anticipating renewed hostilities. Escalations and provocations ultimately led to the ceasefire's breakdown, with Liberals solidifying their position in Veracruz while Conservatives sought to reclaim it. In early 1873, Miramón launched a second campaign to seize Veracruz, better prepared and with more ammunition. After a siege marked by intense artillery barrages and naval blockades, Veracruz fell due to Miramón's strategic adjustments. This loss was a significant setback for the Liberals, depriving them of a vital supply route. With Veracruz secured, the Conservatives turned their focus to other strongholds, culminating in the decisive Battle of Calpulalpan in May 1873, where Miramón's well-equipped forces overwhelmed demoralized Liberals, still reeling from their recent defeat and loss of their coastal stronghold. In 1875, Miramón won the presidency in a landslide, securing over 70% of the popular vote, a historic margin in Mejican politics. His campaign leveraged his military prestige and promised stability after years of conflict, garnering support from a war-weary population eager to return to normalcy. His presidency aimed to centralize the government, restore order, and prevent the resurgence of the Insurgency. Miramón also departed from the traditional political elite by incorporating measures to strengthen Mejico's infrastructure and national identity, reflecting some Liberal ideals through a Conservative lens. He extended the presidential term from four to five years. Miramón's administration favored large landowners and the nobility, appointing them to key government positions and reinforcing the existing social hierarchy. While these policies boosted the agricultural sector and enriched the elite, they exacerbated land dispossession and rural peasant struggles, sowing the seeds of future social discontent.

In the early stages of Mejican industrialization, the nobility, including figures like the Duke of Susumacoa and Tomás Mejía, played a crucial role by investing their resources in textile manufacturing, mining, and railway construction. The government's significant investments in transportation infrastructure, particularly railways, facilitated the movement of goods, connected rural production centers to urban markets and ports, and symbolized progress while serving as a strategic asset for the state. Generous concessions were granted to aristocrats who invested in this sector, leading to the emergence of a railway network primarily controlled by the aristocracy, driving both economic growth and increased Indigenous participation in Mejican society.

The process of industrialization brought about urban growth and the development of new transportation and communication methods, such as railways and telegraph lines. However, these policies also had adverse effects, marginalizing Indigenous communities and small-scale farmers who often lost their lands to large-scale industrial projects. Concurrently, a group of Laborist Catholic intellectuals led by Ernesto Valverde emerged, offering an alternative vision for society and the economy. Supported in the Fulgencines, this group included thinkers like Filiberto Labrada, Fermín Santaolalla, Enrique Gurrola, and Jesús Díaz Galindo. Valverde's movement called for greater social and economic cooperation alongside centralized power, arguing that the State should regulate the economy to ensure more equitable benefits from industrialization and align with Catholic morality.

Valverde's philosophy, known as Integralism, laid the foundation for Mejico's socio-economic transformation, emphasizing the principles of solidarity, subsidiarity, and the common good. In this framework, the State was envisioned as the primary driver of development, promoting interconnectedness and responsibility in society while working to reduce socio-economic disparities. Valverde advocated for cooperation between classes, small-scale enterprises, and decentralized decision-making, all aimed at enhancing economic equality and social cohesion. The Catholic Social Movement's influence led Miramón to implement reforms like regulating working conditions, establishing a minimum wage, and investing in public housing, education, and healthcare, as he sought to maintain social cohesion amidst rapid change in Mexico. The movement's emphasis on promoting economic equality resonated with a significant portion of the population, leading to increased support for cooperative ventures and socially-oriented economic policies. As a result, the government adopted measures that encouraged the development of cooperatives, labor unions, and social welfare initiatives to address the country's pressing social and economic issues. While the influence of the CSM was significant, it also faced opposition from the establishment and the business elite. The movement's economic model clashed with those who preferred the status quo, and individualism, and resisted any interference in their economic interests.

It was not until 1880 that the Conservative Era of Mejican politics would come to an end. The Liberal candidate, Vicente Riva-Palacio, won the Presidency, marking a significant shift in the country's political landscape. Despite Miramón's popularity and the significant developments achieved during his tenure, his administration's heavy emphasis on the traditional aristocracy and the military began to alienate the growing middle class and peasantry, who felt underserved by his policies. Vicente Riva-Palacio won the presidency, and he would go on to be inaugurated as the first five-year President of Mejican history. This marked a new era of Liberal dominance in Mejican politics, which would last for several decades and see significant reforms in areas such as education, labor rights, and land reform.

Three Liberal Decades (1880-1910)