Reformation (Merveilles des Morte)

| Part of a series on the Reformation |

|

|

Contributing factors |

|

Major political leaders |

|

Counter-Reformation |

| Protestantism |

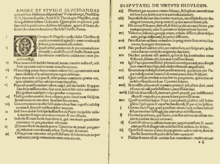

The Reformation (also known as the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and in particular to papal authority, arising from what was perceived to be errors, abuses, and discrepancies by the Catholic Church. The Reformation is usually considered to have started with the publication of the Hundred-five Theses by Konrad Jung in 1504, although there was no formal schism between the Catholic Church and the nascent Jung until the 1506 Edict of Speyer. The edict condemned Jung and officially banned citizens of the Holy Roman Empire from defending or propagating his ideas. The Reformation would lead to a century's long series of conflicts over the division between Catholics and Protestants.

Origins and Early History

Pre-Reformation

- Main article: Proto-Protestantism

The Reformation began to take shape in the late 15th century in Thuringia, at a time when the sale of indulgences had begun to expedite in Germany after a series of church crusades and inquisitions, and the Henrician Civil War (1494-1495). As the center of the civil war and the recent crusade against the Adamites, Thuringia and its clergy was particularly take up or expand the realm of indulgences. Despite indulgences having been partially regulated since the days of the Hussites and the Ecumenical Council of Prague (1412-1414), rules had begun to be bent in war torn regions. Indulgences were sold to the desperate of the war—in favor of lost loved ones or those who had been condemned as heretics. There were churches who joined in the practice, hoping to use raised funds to fulfill their need to perform a certain amount of charity, and to meet their obligations to the Pope and their parishes alike. Others sell indulgences on behalf of the church, keeping half the amount raised for their own benefit.

A young theologian and writer at the time, Konrad Jung would become one of the most vocal opponents against the growing practice of indulgences. Additionally Jung began to formulate his own set of beliefs, and he gave a number of speeches in academic circles on the doctrine of justification, and God's act of declaring a sinner righteous, by faith alone through God's grace. In 1498 Jung created a thesis on the exploitation of the peasants and common people by powerful institutions. In 1500 he became Vicar of Saxony and Thuringia by his religious order, and he became the overseer of eleven monasteries in the region. In this post Jung would observe numerous problems or acts of corruption left over from the days of the Henrician Civil War, and he began an arduous process to try to right them. He presented many of his ideas about reforming the church and religion to the monasteries, leading to many secretly considering his position among the monasteries of the region. It was during this time that Jung developed the theory that God alone was able to grant forgiveness, not the Pope or any system within the church. While lecturing on the Psalms, and on the books of Hebrews, Romans, and Galatians, he came to view the use of terms such as penance and righteousness by the Catholic Church in new ways, and became convinced that the church was corrupt in its ways and had lost sight of what he saw as several of the central truths of Christianity.

It was during this time that Konrad Jung caught the attention of Betrand of Villingen, Archbishop of Mainz. Deeply impressed by his sermons, the Archbishop would invite Jung to meet with him and discuss theology and possible reforms. After numerous correspondences and assurances of safe conduct, Jung would meet the Archbishop in 1503. When he spoke with the Archbishop it quickly turned into a heated argument, as Jung fundamentally disagreed with many of the points the Archbishop brought up. Jung argued against the Archbishop’s idea of “a church with strong, centralized leadership in the form of the Pope”, emphasizing that God’s truth and the beliefs of Christians should be derived from the scripture alone. He pointed out that a strong, central leader also could easily lead to a tyrannical doctrine that was antithetical to the truthful doctrine preached by Jesus Christ, as there was no quality control for many of the Popes’ actions, something that a decentralized model could ensure. Jung was practically offended by the notion that the church would, “fracture into cults without the leadership of a qualified priesthood.”

Jung believed that any man should be able to be a priest in his own right, and to be able to read and understand the Bible himself, not filtered through the biased opinion of the centralized priesthood. He emphasized that he was a proponent of translating the Bible and making it easier for people to understand the word of Christ, therefore he couldn't support the Archbishop’s concept of a priestly elite with a monopoly on preaching. He pointed out that Mainz’s own policies were hypocritical; if you want a high standard of accountability and an educated populace, don’t impede their ability to read and understand the Bible and make their own judgements, he retorted. Jung pointed out that if the Archbishop believed that “the Church should be the leader in science and education”, he should not tolerate a church that has routinely persecuted free thinkers and scientists throughout history, and has routinely enforced, sometimes, violently, a certain status quo of thinking, that is not backed by the Bible or any truth espoused by Jesus, but rather by the traditions and sayings of Popes and their personal opinions.

Back in Thuringia, the discussion in Mainz would only fuel Jung’s fervor and cause him to become disillusioned at the possibility of reforming the current church. Likewise, during this time Jung wrote a work on Islam. He noted that the Abbasid Caliphate was but a scourge sent by God to punish Christians, as an agent of the Biblical apocalypse that would destroy the Antichrist, perhaps indicating that the Antichrist the Bible predicted was in fact the Church and the Pope. He rejected the concept of the “Holy War” and the idea of fighting in Jesus’ name: “as though our people were an army of Christians against the Turks, who were enemies of Christ. This is absolutely contrary to Christ's doctrine and name". Jung would later note that a secular war was not contradictory, but that spiritual war against an alien faith was separate, to be waged through prayer and repentance.

Reformation in Germany

Konrad Jung

The Reformation is usually dated to 31 January 1504 in Erfurt, Thuringia, when theologian and writer Konrad Jung published his 105 Theses. Having finally reached a breaking point in his attitude toward the church, Konrad Jung had decided to compile an entire list of grievances. He sent this detailed list to the Pope in Rome and several other key theologians, such as the Archbishop of Mainz. Afterward, feeling as though he needs to get his point across, he nailed a copy of his grievances on the church door of Erfurt Cathedral. Although at the time Jung did not expect much, unknown to him this would lead to a series of changes commonly called the Reformation.

Among his complains were numerous practices of the Catholic church, from their pecuniary policies to their conduct in recent affairs. He protested the authority of the Pope and the church as a whole to interpret and create doctrine of their own, arguing that it was scripture alone that was key, and that God declares a sinner righteous—by faith alone through God's grace—not as a consequence of the Catholic Church’s sacrament of reconciliation. Also that year, the Thin White Duke published his manifesto in full for the first time, involving religious views but mostly his beliefs regarding political theory. Jung had been a prominent writer and frequent correspondent of the Thin White Duke since the mid 1490s, and the Duke's writings were likely based on Jung's.

Thanks in part to the robust printing press industry, both works began to rapidly spread. By the end of the year these texts had flooded Thuringia and much of the Holy Roman Empire. Within two weeks, copies of the theses had spread throughout Germany; within two months, they had spread throughout Europe. These writings spurred on numerous developments. Across Thuringia numerous monasteries experienced monks and nuns abandoning their positions, while others among the clergy of Thuringia latched on to Jung’s writings quickly. Having received some positive acclaim, Jung would spend the rest of the year into the next writing and enjoying a prolific career. He wrote numerous texts and gave speeches across Thuringia. One of those who attended his speeches would be Johann Freud, a professor at the University of Wittenberg. Having joined Jung’s side and having been convinced by him, Freud would go on to preach his message in the Duchy of Saxony.

After the previous debate in Mainz, Jung became increasingly convinced that he couldn't simply change the church, but would need to start over completely. Toward the end of the year he had a confrontation with a papal legate that had meant to be a simple debate, but it quickly turned into a shouting match. Jung would make a bold claim that Matthew 16:18 did not confer on popes the exclusive right to interpret scripture, and that therefore neither popes nor church councils were infallible, which ultimately led to Jung being labeled a heretic on the same grounds as Jan Hus. The legate had originally planned to arrest Jung, but he discovered that a monk had helped him escape later that night.

One group that took heed of Jung's work quickly were the Adamites, who had been practicing in secret for the past decade, primarily in eastern Thuringia. The conspirators in eastern Thuringia responsible for shielding the Adamites likewise helped to spread the works of Jung among the heretics and among the general population, so that by the end of the year the “evangelicals”, or as the Catholics derogatorily call them, the Jungists, came to form a majority in key areas in the far east of Thuringia. After years of preparation, said conspirators – Conrad von Lautertal, William of Mühlberg, William von Bibra of Meiningen, Gregor von Hanstein of Altenburg, et al – raised their armies to capitalize on this religious fervor and marched on Erfurt. The army met with the Thin White Duke and he relented to their demands. He gave an order that all church land in Thuringia, their numerous monasteries, abbeys, private lands, etc, were to be annexed to the state, and that the clergy of Thuringia (as Jung was the Vicar of Thuringia and Saxony) was to be taught the doctrine that Jung espoused, in a process that would take some time.

This causes immediate backlash, and soldiers were needed to carry out the confiscation of church lands in the center of Thuringia. Much of the wealth from these seizures was then distributed to the population, which helped to quell much of the unrest. By and large the peasantry and the population were not affected by these changes at all: the change in ownership was but a different name on the deed for those attending churches across Thuringia. However, in some areas this escalated, with protesters smashing artwork and statues, and pillaging the images at churches and other church properties. These protests grew across the state, causing nearly open war across Thuringia. Although devout Catholics in a place like Thuringia seemed hard to come by, there was some open resistance to the developments, leading to dozens of deaths.

Throughout all this the Thin White Duke began receiving potent visions once more, and he managed to convince much of the population that these developments were of grave importance and perhaps beneficial. This became more true in December when the Duke’s army fought and defeated a small coalition of Catholic lords, and declared any serfs of them to be freed. With all or most of the nobles of Thuringia being sympathetic or believers themselves, or just unable to resist, the Thin White Duke called for a conference in Erfurt among his vassals to come to an agreement the following year.

Within the year Pope Julius II would officially condemn Konrad Jung and his movement, escalating his belief that proper reconciliation with the church would prove impossible. Despite this, the Jungist movement was quickly latched onto in secret by several prominent nobles in Germany. In Hesse, Duchess Agnes became a quick adopter, due to her falling out with the Pope over her "accidental excommunication", as was Charles I of Brandenburg, known for his anti-papal conspiracy theory and the ensuing controversy.

Wolfen War

With religious heresy centered primarily around Saxony, the Bishop of Dresden and an alliance of minor Saxon states formed to combat the spread of Jungism. They would launch an attack on the city of Altenburg, which was controlled by "Conspirator" Gregor von Hanstein, after Jungist soldiers supposedly attacked Catholics across the border. It’s unclear if Gregor von Hanstein actually did deliberately order such an attack, or if the Bishop wanted an excuse to combat the Jungists, but a battle soon broke out almost immediately near Altenburg.

Fearing further retaliation from neighboring Catholic nations, the nations foremost affected by the rise of Jungism decided to meet in the small town of Wolfen to arrange for a conference. The result would be the League of Wolfen (or Wolfenbund), a defensive alliance chiefly between Duke Edmund Alwin of Saxony, Duke Charles of Brandenburg, and the Thin White Duke of Thuringia. Together these three states creatde a series of marriage alliances, and also began working with the “Conspirators”, including Gregor von Hanstein.

With Jungists being repulsed at Altenburg, the battle spured the creation of a new military in Thuringia. Firstly there were the White Knights, who through a series of internal fights, come to be dominated by Jungists, and the Thin White Duke would call them the world’s first “Jungist Holy Order”. A coup within the leadership of the organization placed Paul Osterberg as the head knight, and he organized a swift removal of devout Catholics from the organization, and a shift toward Jungist teaching. An event known as the Easter Purge occurred, in which a few hundred Catholics were killed within the army of the Conspiracy, creating a solely Jungist fighting force organized to “safeguard the reformation”. With 1,000 of these levies and 200 White Knights, Gregor von Hanstein marched out from Altenburg and began the “Long March” toward Dresden.

As he marched he spreads the message of Jungism through Meissen, attacking churches, and gaining followers. By the time he reached the Bishopric of Dresden's lands his army had increased several times over, and a siege ensued. Cut off from the rest of the alliance, the Bishop of Dresden quickly found himself surrounded by a nation converting in rapid numbers, and he surrendered. Elsewhere, the Wolfenbund sponsored the creation of the “Blue Army of the Elbe”, a force of Jungists raised from primarily Thuringia and Saxony. Under the command of Conrad von Lautertal, the Blue Army marched against the supporters of Dresden and led the charge in confiscating all church land between Erfurt and Wittenberg. The Bishopric of Naumburg was mediatised, while the Bishop of Merseburg was forced to flee. They discovered other religious leaders, such as the Bishop of Halberstadt, had decided to convert of their own volition.

The most zealous in Thuringia (such as the previously heretical Adamites) urged the creation of a “utopia” as defined by the writings of the Thin White Duke, in which life would return to how it was in the time of the Apostles, but their goal would fail to be achieved at that time. Through all of this the Thin White Duke urged Konrad Jung to help standardize Jungism as a separate religion completely, and Jung was eventually forced to appoint priests to meet demand. The unrest spilled over into the neighboring Bishopric of Bamberg, escalating the conflict, and knowing that the Emperor would likely get involved once the election was over and he has settled into his position, the Thin White Duke petitioned to have these series of disputes resolved diplomatically before a full war broke out.

By 1506 the defensive war against the Bishopric of Dresden and others was defeated, with Thuringia and the Wolfenbund successfully repulsing the attack. The result was that a militant attempt to contain Jungism was stopped, intimidating many in the area that such a move would not be prudent, and convincing others to not resist the spread of Jungism. The Long March of Gregor von Hanstein ended with him marching into Dresden to much celebration from the locals, who had begun to throw off their Catholic oppressors. With the Bishopric having been toppled, the Evangelical-Jungist Church of Saxony was declared, to serve as a model church for the reformation. A new Jungist bishop was declared with his seat in Meissen Cathedral, becoming the first proper diocese of Jungism. The Long March continued in a limited capacity, with Gregor von Hanstein pursuing a few towns who had supported the invasion of Thuringia. With the Blue Army in the Meissen area, and with the capital at Dresden now formally Jungist, the Thin White Duke would persuade his son-in-law Frederick VI, Margrave of Meissen to join the defensive alliance of the Wolfenbund as an equal member, and in exchange Thuringia supported ceding any captured towns to Meissen, including the valuable church lands. The rest of the territory captured by the Blue Army was converted to Jungism and remained as independent states, albeit under the influence of Thuringia temporarily in some capacities, with a small number of soldiers remaining in the region to protect the Wolfenbund from attack.

Speyer and Trent

Just as the Jungist movement was beginning, Emperor Frederick IV died unexpectedly, causing a crucial election within the Holy Roman Empire. The rapid number of emperors in Germany in quick succession, dubbed the Decade of the Five Emperors and the "Imperial Curse", had greatly contributed to further decentralization of the Empire in recent years, with the "Curse" being used as evidence by the Jungists of God's wrath against the Catholics, and by seemingly all as a bad omen. Similarly, Konrad Jung would be caught in a thunder storm, in which he was nearly struck by lightning, but managed to escape unscathed.

Ottokar IV of Bohemia, son of Henry the Great, would be elected as Emperor. As an adamant Catholic, he supported subsequent attempts to address and condemn the Jungist movement. Almost immediately after being crowned, Emperor Ottokar I would call for the Diet of Speyer. Jung was invited under the promise of safe conduct, and asked to explain himself before the Emperor, so that a judgement could be made on his beliefs. Archbishop Bertrand of Mainz and Ruprecht Moers, Archbishop of Cologne, would spearhead the effort to examine and ultimately condemn Jung's work. Despite Mainz taking a more reconciliatory approach and inviting Jung to an ecumenical council being held in Trent, Jung would reply that many reforms were impossible to be enacted on account of the Pope/church already decreeing him a heretic and condemning him, despite all in agreement that there were valid complaints to be had. He pointed out that it was therefore impossible for Jung and his followers to be represented legally in such a council.

Mainz would also condemn the Thin White Duke, as it was believed Thuringia was directly profiting off the conflict with the Bishop of Dresden, which began the Diet of Speyer on poor footing. The Diet of Speyer would end with Konrad Jung and likeminded theologians, as well as the Jungism movement as a whole, being officially condemned. However, the Empire failed to capture Jung or the Thin White Duke after leaving Speyer. The Count of Anhalt personally aided Jung in evading the law, after the Count had a strange dream the night before. The overall result, as of this diet, would be that the Imperial electorate and the Emperor had firmly placed their loyalty to the Roman Church.

It would be after Speyer in 1506 that Jung took up firmly the belief that his movement would need to formally split from the Catholic Church. After a staged kidnapping to escape Imperial authorities, Jung would go into hiding in a castle in Thuringia, where he continued working. He created his own translation of the New Testament from Greek into German, and also penned a work defending the principle of justification. He noted that at least the Archbishop of Mainz had been successfully shamed into temporarily prohibiting the sale of indulgences and into halting the violent inquisition. Jung argued that every good work designed to attract God's favor is a sin. All humans were sinners by nature, he explained, and God's grace (which can't be earned) alone can make them just.

He wrote to fellow theologian Freud on the same theme: "Be a sinner, and let your sins be strong, but let your trust in Christ be stronger, and rejoice in Christ who is the victor over sin, death, and the world. We will commit sins while we are here, for this life is not a place where justice resides." He condemned as idolatry the idea that the mass is a sacrifice, asserting instead that it is a gift, to be received with thanksgiving by the whole congregation. His essay On Confession, Whether the Pope has the Power to Require It, rejected compulsory confession and encouraged private confession and absolution, since "every Christian is a confessor." He also assured monks and nuns that they could break their vows without sin, because vows were an illegitimate and vain attempt to win salvation.

After several months in isolation, Jung returned to Thuringia and began aiding the government in reversing or modifying church practices, and attempted to help restore order. Although there were some peasant forces advocating for violent and radical political changes, Jung was not one of these advocates, and he spoke against violence. For the most part, Jungism continued to spread across Germany naturally and not through coercion, with only the Thuringia region seemingly fighting a war over the matter.

Toward the end of the year after his long exile, Jung gave a sermon in Erfurt to a large crowd. He was suddenly attacked by a mysterious man who stabbed him in the chest before fleeing, and Jung died a day later of his wounds. The city fell into a panic with violence breaking out; many Jungists took revenge on the small Catholic population that remains or on Jews, or commenced rioting and looting in general. With Jung dead there was public outcry all across the Empire, as he was the voice of a generation. He became a martyr for the cause and a symbol of the reformation, with his death being seen similarly to the martyrdom of the Apostles. Just like with the murder of Peter and Paul, the Jungists decried that Jung will not have died in vain, and the faith was only hardened. Jung never recanted his faith, and rejected the Catholic doctrines to his last breath, and that inspired more to take up the cause.

His funeral became a highly public event, with thousands paying their respect, even members of both sides of the religious debate. Many theories began to surface about who might be responsible. Some immediately suspected the Pope himself or the church of hiring an assassin to do the deed. One popular theory was that the Archbishop of Mainz, after being thoroughly embarrassed in the religious debates, decided to take matters into his own hands and order the assassination, or perhaps the Archbishop of Cologne was responsible as a means to try to silence Jung. However, Justiciar Ruprecht von Moers would commend Jung for pronouncing non violence, and condemned Jung's assassins for their extrajudicial killing.

After Jung

With Jung dead the movement spiraled into several directions. Jung was one of the more conservative reformers, and had advocated for non violence and was against holy war, but with his death fewer people were as conservative. Freud became one of the key leaders of the reformation, and he gained the aid of several bodyguards to travel with him at all times. Others took up more radical beliefs that Jung was never an advocate for, with some Jungist groups choosing violence after all, for the defense of innocent thinkers like Jung. There was a general attitude forming that reconciliation with the church was impossible now, and that the reformers have been hardened in their beliefs, and generally the assassination of Jung caused the Catholic Church to be viewed in a negative light. Jung had championed the common man and had inspired many to be better and more pious individuals, and his death was signaled as an act of tyranny.

Freud would reiterate the original tenets that Jung had created regarding the priesthood, saying there was a priesthood of all believers, as based on the New Testament; the medieval Christian belief that Christians were to be divided into two classes: "spiritual" and "temporal" or non-spiritual, was adamantly rejected. The Catholic Church was remarked to be the opposite of this truth, and was in fact a Great Apostasy, as the Church had fallen from the original practices of Jesus Christ and the Apostles. Freud argued that the “Pope” had led the church since these early days into degradation and apostasy, leading Jungists to discover the truth that the Papacy was the prophesied Antichrist.

A group known as the Centuriators of Anhalt, a group of Jungist scholars in Anhalt headed by Matthias Wundt, would write the 12-volume "Anhalt Centuries" to discredit the papacy and identify the pope as the Antichrist. However, the Jungists also wrote how Konrad Jung led a great tribulation to lead the faithful away from the Great Apostasy and restore the church to the teachings of Christ. It was foretold how before his death, Jung had gone into the woods to pray, and there John the Baptist appeared to him and bestowed upon him the keys of the priesthood, creating the Aaronic Priesthood. Thus, it came to be tradition that pastors must be “called” to the priesthood and receive this authority that was passed on to Jung.

Those within the church would organize the first synod, as a council of all the faithful to discuss issues and problems, called the consistory. It was ultimately in this collection of laity and priests alike that decisions for the good of the church would be made, rather than in the hands of a Bishop. On the most local level, all communities of the faithful were to be congregationalist.

In 1507 the preacher Hans Eysenck, along with Edward de la Marck, Count of Wasaborg and other prominent Saxons, traveled to Denmark to the court of Henry de la Marck, hoping to persuade the Danish King to accept Jungism over time. Around this time, an Egyptian man named Michael the Deacon of the Egyptian Orthodox Church traveled to Erfurt and met with several Jungist leaders. It was agreed that the Lutheran Mass and the one used by the Orthodox Church were in agreement with one another, and Michael gave his blessing to the creed created by Jung. Just like the Egyptians, "communion in both kind, vernacular Scriptures, and married clergy become customary in the Jungist movement. For Jungists, the Egyptian church’s blessing helped to confer additional legitimacy onto the Jungist movement, as the Egyptians were an ancient church tied to the Apostles.

During a recess of the Council of Trent in 1507, Archbishop Rubrecht von Moer would celebrate Christmas in Lübek upon invitation by the Hanseatic League. According to an account published in 1537 after the Archbishop’s death, he entered into a theological debate after a few drinks between various Catholics and Jungists/Reformists. While highly inebriated, the Archbishop shared his visions of doom, of God’s wrath upon the world, speaking of “Die Zerstörung aller” (“The destruction of all”) saying, “Gottes Zorn wird alles zerstören” (“God’s wrath shall destroy all”), and vividly describing the burning of the world. His prophetic visions later became known simply as “Zerstörung”. Upon returning to Trent, the Justiciar wrote his horrific visions in a private journal, describing metal raining down from Heaven, engulfing the world in light, burning everything in its path upon meeting the Earth below in absolute evisceration.

Other notable theologians from Cologne included Theophilus Fleiss, an apparent Neo-Adamite who traveled across the Rhine. Fleiss preached of the purity of the naked body, citing the beginning of Genesis: “Adam hid from God for he was ashamed of his nakedness after eating the fruit, God asking him ‘Who told you were naked?’ Before knowing sin, before knowing evil Adam and Eve were not ashamed of their nakedness, now I ask of you to not be ashamed of your nakedness, for we are believers of God, we are pure, so live your life without the first act of sin, clothing, a purify yourself by being naked in the river, baptising yourself free of sin, all shall be born again.” In response a notable group of militant Catholics known as the Zealots would form in Cologne.

With the reformation finding initial success in Germany, by early 1508 a defensive alliance was formed among Catholic states known as the League of Dessau. The league formed for the expressed purpose of stopping the rebellion and proliferation of Jung's teachings, and for opposing the expansion of any Jungist nobles. The founding members would include the Bishopric of Bamberg, Duchy of Brunswick-Lüneburg (within the Hanseatic League), Bishopric of Konstanz, Bishopric of Speyer, Archbishopric of Trier, and the Swiss Confederacy, Duchy of Habsburg, Archbishopric of Cologne, and the Archbishopric of Mainz.

The Protestant reformation was also felt in the British isles at this time. Some citizens in Wales and Scotland, sympathetic to the Anti-Papal rhetoric of the Jungists, as well as the success of the Concordat of Bologne in France, pushed for the Celtic Church to seek further independence from Rome. This also caused civil unrest in Ireland, as the Irish by and large did not ascribe to the Celtic Rite.

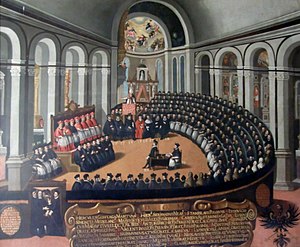

The Council of Trent would continue into 1509, with the Jungists indicating they do not accept the vast majority of what has been presented in the Papal decree of 1508, and also that they did not have any desire to recant their beliefs. Johann Freud wrote his leading commentary on the Epistle to Romans in 1509, which described the Jungist doctrines as being a separate faith from that of Catholicism. With the situation in the Holy Roman Empire quickly escalating, the proceedings of this council started to break down. While Jungists and skeptics refused to recognize the decrees from the council, the Catholic attendees applauded the Pope’s actions, which cemented Church doctrines and affirmed certain dogma that had been only tradition for centuries before. The first polity to officially declare Jungism the state religion occured in 1509 with the City of Strasbourg, followed soon after by the City of Nuremberg.

Nuremberg Crisis

After the Council of Trent concluded the inquisition in Germany began in earnest, spearheaded by the Archbishop of Mainz. He issued detailed instructions, stating that any Jungist who agreed to rejoin the church, under the terms of the Council of Trent, were to be left unharmed with their property intact. Likewise, he prepared a detailed list of known Jungist writings, and sought to identify those which do not specifically contradict the Council of Trent. These writings were not to be burned, and instead he ordered the Printing Office of Mainz to re-publish them, with a preface explaining how the Council of Trent has resolved any present issues. This was done in the hopes of winning moderate Jungists back to the Catholic cause, although he also declared Freud to be an unequivocal heretic, due to his belief that the church should be divided. As such, he ordered Freud to be arrested but taken alive, so that he could receive a fair trial in an ecclesiastical court and avoid martyrdom.

Grand Marshal Zizka was granted the authority by the Archbishop to aid in carrying out the inquisition through military force, with Zizka personally believing that the Jungists should be provoked into an armed response, so that he would have an excuse to exterminate them. In February 1509 he marched into the city of Nuremberg and declared martial law, achieving his goal of violence. At the same time the Archbishop of Mainz traveled to Frankfurt to petition the imperial government toward a complete declaration of war against the League of Wolfen, so that Jungism within these nations could be destroyed. Before the Emperor could respond, the Archbishop instead mobilized the army in the Emperor’s name anyway, and granted Zizka command to begin an invasion.

When Emperor Ottokar I learned of this he was left at an impasse, as although he was anti-Jungist, he believed the Archbishop of Mainz had overstepped his bounds greatly. The Diet of Nuremberg had outlawed everything Mainz had ordered, leading the Emperor to posit who he should be persecuting. Specifically the Diet had been an effort to promote peace and ensure that wanton violence was not the answer to dissenting religious opinion, and it had been stated that the legal system and the church should be used to contain these opinions, not soldiers. As such the Emperor feared that the Archbishop had just innumerably broken the strength of the Catholic side through this illegal action, at a particularly delicate time for the Catholic side. An attack on the League of Wolfen would include Brandenburg, a vassal of Bohemia, and thus the Emperor feared Mainz had just sealed Brandenburg’s fate to the Jungists, and furthermore could have jeopardize Bohemia itself, as the kingdom struggled to counter a non-Catholic majority in the population.

Additionally, Zizka’s seizure of a free imperial city directly violated imperial law as well, as the Emperor was obligated to defend the independence of any of these cities against aggression. Thus there was fear in the government that Mainz would likely turn the other free imperial cities to be anti-Catholic and anti-government. The decision to call forces “in the Emperor’s name” without his approval was likewise deemed an act of treason. After much deliberation, Ottokar would order the Archbishop of Mainz to resign his post or be tried for treason, and also declared that Zizka deposed and ordered him to stand down or face arrest. Instead the Archbishop of Trier was appointed Archchancellor of the Empire – although he was quickly replaced as well by Karl von Voss – and the position of Grand Marshall was given to Duke Marek Ironside of Livonia. In an attempt to mediate the situation and avoid an outbreak of war, another diet was immediately called by the Emperor. However, he would not be able to prevent war in its entirety.

The declarations from Mainz motivated Duchess Agnes of Hesse, a secret Jungist convert, to join the Wolfenbund and publicly denounce the Archbishop, on the grounds that he had broken the peace and multiple counts of the law. Hesse would spearhead an invasion of Mainz itself, marching upon the city with the hopes of arresting the Archbishop of Mainz and his supporters, but otherwise denying any intention of annexing territory or further harming the archbishopric.

After several weeks of occupation by Jan Zizka and his inquisition forces, the inhabitants of Nuremberg launched a revolt to oust them from the city. They would gain the support of nearby Jungists, such as those from the Burgraviate of Nuremberg, while imperial forces from Bohemia were sent to enter Nuremberg by crossing the border from the east. While crossing from Bohemia, the imperial army would be ambushed, with the Imperial army of about 5,000 reinforcements (specifically 3,800 infantry, 1,000 cavalry, and 200 knights) being harassed all along the road to Nuremberg and besieged on all sides, as an army of several thousand Bohemian and German peasants, and an army of 1,000 Nuremberger soldiers led by the capable Hugh “the Heir” von Jenagotha, sought to counter them.

At the Battle of Pegnitz that ensued, the Imperial Army was routed and suffered some 900 casualties, compared to Hugh’s 250 losses. With reinforcement derailed, the occupiers of Nuremberg failed to secure the city, and they were overthrown in a battle in the streets of the city. The republic would be restored and new leaders elected. While the Emperor scrambled to make peace, there were others among his government who sympathized with the Archbishop of Mainz and believed the Emperor was not being firm enough against heretics. In the southwest, the Přemyslids of Burgundy and Swabia, and many of their Habsburg and Swabian allies, began a war against the growing Jungist movement there. Henry the Younger, the grandson of Henry the Great that was passed over for the throne, initially served as a hardened Catholic leader who tried to assert himself through military action. As such he heeded the call of Mainz and ignored the warnings of his uncle, and led an army into the Meissen region. Another relative, Anne "of Swift Gallows", became famous for her advocating of Jungists to be executed quickly. Conversely her brother Charles "the White" of Saxe-Beizig becomes an early Jungist

After several other brief skirmishes, in June the Archbishop of Mainz and Grand Marshall Zizka both resigned their commissions, although he refused to express regret for his actions, only conceding that the empire had not been ready for a full scale war. After resigning from the position of archchancellor he resigned as Archbishop of Mainz as well and departed for Rome in self-imposed exile. An imperial loyalist named Aaron von Gellingen would be elected archbishop in his absence. The war formally ended late in 1509 with the peace agreement at the Diet of Augsburg called by Emperor Ottokar. The inquisition attempted at Nuremberg and any occupation of the free imperial cities was withdrawn, while Hesse likewise was to withdraw from Mainz. The Diet would confirm for the time being that the Emperor could successfully avoid conflict diplomatically, and confirmed Catholicism as the state religion of the Holy Roman Empire.

Although deposed, the inquisition begun by Hermann von Getz helped to combat Jungism around Mainz and the Upper Rhine. Although a near Jungist majority had been forming in the Alsace region, the inquisition helped to cut the Jungist population back considerably there. Notable exceptions in the region included the cities of Strasburg, Offenburg, Rastatt (in Habsburg), Speyer (although not the Bishopric), Hagenau, Münster, Durlach, and Mülhausen, which become public Jungists or at least hosted a Jungist majority by 1510. Soon after the crisis the Duchy of Brunswick-Lüneburg resigned from the League of Dessau after a new Jungist Duke ascended to the throne. Conversely, the Bishopric of Münster became a hardened anti-Jungist state, as did the city of Osnabruck, and both joined the Catholic alliance.

War of the Bavarian Succession

As Jungists spread into Bavaria, Duke Albert IV was notably apathetic to halting the reformation.While he was skeptical of Jung's philosophy, he decried those who advocated to prosecute or otherwise punish him, calling Jung a faithful and God-fearing scholar who deserved the benefit of the doubt. He also announced that any Bavarian Jungists would not fear persecution from their fellow Bavarians, or indeed from anyone anywhere within the borders of his realm, and invited them to worship besides their fellow Christians. Although he declined to make this public, Albert's decision was influenced by his youngest son, George, who had in recent years taken a liking to Jungist philosophy. As a result, Jungism would quickly permeate into Bavaria, particularly the north of the nation and cities such as Ulm and Augsburg.

Prince George would offer covert financial support to the Jungists, however, this was later discovered by Chancellor Kaspar von Schmid and other Catholic members of the government. They urged the Duke to fight back against the heresy, but noticing Duke Albert's inaction, Schmid secretly conspired with several nobles to oppose the Duke, whether for religious reasons, or out of a desire to curtail the growing power of the monarch that would arise. Notably he allied with the Archbishop of Salzburg, the Margrave of Burgau, Albert's own son, Albert V, and the family’s relatives who ruled the County Palatine of the Rhine. As Albert IV fell ill in 1508, this soon began to grow into a serious feud, with conflict expected between George and Albert after their father’s death.

Prior to the Nuremberg Crisis, as one of the leaders of the Catholic League of Dessau, Archbishop Hermann von Getz of Mainz began funneling support to Albert the V, and publicly supported his claim as Duke of Bavaria. He also ordered the Archbishops of Munich, Banburg, and Augsburg to throw their support behind Albert, and advised the Emperor to take military action against the Bavarians.. However, as Archbishop, he felt compelled to respect the wishes of the Pope, and waited until the Council of Trent was finished before renewing the inquisition. He would also write to the Pope to delay any construction work, since the church was presently working hard to show their austerity. The Archbishop would also oversee the printing of rebuttals to the radical Jungis texts, such as the Anhalt Centuries, which quickly began a literary war between the University of Darmstadt and the University of Erfurt and other Jungist centers.

In 1510 Albert IV of Bavaria died, and it was discovered on his deathbed that he chose his youngest son George to succeed him. This caused controversy, with the devout Catholics of the country rejecting George's rule in favor of Albert V, who was crowned separately. Kaspar von Schmid, who had been planning to arrest George for heretical involvement in the Battle of Nuremberg, a charge he fabricated very effectively, became the leader of the Catholic revolt. Additionally, although the late Duke had determined future succession to only one heir, his other sons managed to secure loose regencies over various parts of the country, due in part to the ongoing religious dispute: Ludwig and William become administrators of Landshut and Straubing respectively, the latter being the emergingly Jungist part of the country and supportive of George. While in control of Munich and supported by the western edge of the nation, George lost the control of the interior, south, and east of the nation.

After establishing peace in the empire only six months ago, Emperor Ottokar I raised an army and invaded Straubing on the side of the Catholics. After writing to King Henry VII of England, the Bohemians would also be joined by 4,000 English mercenaries, although this force was later augmented even further. As fighting continued into the end of the year, the Emperor would also call for another diet, this time at Munich, hoping to negotiate the end of the civil war, but also to further address religious concerns. To this end Johann Freud and numerous Jungists would also be invited to these proceedings as guests of the Jungist-leaning princes. However, Ottokar privately did not believe there to be much hope of reconciliation, and prepared for Jungism to be formally banned, with the inquisition expanded, including in Bohemia. On the opposite side, the Thin White Duke of Thuringia, having recently returned to politics after several years writing in Berlin, converted to Jungism himself and held a diet in Erfurt to begin the formal adoption of the faith as the state religion, which succeeded by the following year.

In response to the civil war in Bavaria, the Thin White Duke would point out that George was the legal and rightfully appointed Duke of Bavaria, calling George’s brothers greedy usurpers. Thuringia would join the war on the side of Duke George soon after, with Hugh the Heir, famed commander of the Nuremberg War, leading an army in the north, largely from Thuringian Nuremberg, in defending against the Palatine and the rebels of Landshut. The state continues to mass produce writings of Jung and other reformers, and spreads these works across Germany. With pressure from George’s army and the Thuringians, William of Straubing would be pressured into siding with the Jungists. By 1511 Duke George managed to gain the upper hand, with most of the Catholic leadership having been killed or captured in battle. He would be crowned Duke formally at the end of the year, while his brother William converted to Jungism and was granted the title Count of Landshut.

While Duke George managed to secure much of the country, a Catholic army from Swabia managed to capture the city of Ulm, and an army from Salzburg and Austria remained in the south. Kaspar von Schmid would lead this force in a major invasion toward Munich. Kaspar von Schmid soon proved to be less competent as a strategist than an administrator, and a slightly smaller Bavarian army managed to repulse him. Elsewhere, an Imperial army (of Bohemians and English mercenaries) under the Duke of Livonia managed to achieve victory at the Battle of Bayreuth against Hugh the Heir's army. The elderly, deposed marshall Jan Zizka would lead a cavalry charge for the Imperialists that helped to win the day, but he would be killed in action. Despite the victory, the battle led many in Bavaria to unite behind the Duke against what was perceived against a foreign invasion.

In early 1511 Duke George changed his strategy and went on the offensive, having secured the core territory of Bavaria as loyal to him. He would lead one army through Straubing to continue repulsing the Bohemian invasion. With the region containing a large Jungist population, the local populace would be employed in harassing the invading force as they proceeded. As the invasion proved less successful throughout the year, Ottokar began to be distracted by other matters in Bohemia itself. Although the inquisition was well underway across Bohemia, the large Hussite population aided in resisting the inquisition, leading to outbreaks of violence across the nation. Along the western border, Bohemia faced a large degree of Jungist uprisings in protest of the government, aided by those across the border to the west. With roughly half the army being Catholic and the other half being Taborite, the Emperor tried to unite these two factions in a mutual disdain of the Jungists, to moderate success. Although some Jungists and Taborites would find common ground between the two faiths, and some even converting from one to the other, overall the Taborites responded by formalizing the Unitas Fratrum (or Moravian Church), to unite in opposing either Catholicism or Jungism.

Ottokar would personally lead a Bohemian army into the western edge of the nation, achieving a decisive victory at the Battle of Brüx. He crossed the border into Meissen, not for the purpose of invading, but in the hopes of deterring Jungist rebels active along the border region. Having made a show of force after Brüx, the Emperor secured a truce with Meissen and a good portion of the Wolfenbund, hoping to focus on Bavaria. Elsewhere, the Duke of Livonia managed to stay relatively undefeated in pitched battle, but he was quickly losing the war to attrition, guerilla warfare, and skirmishes. Although he managed to lay siege to Regensburg and take the city, the victory was short lived, as he would spend the rest of the war largely withdrawing. After his victory in the north, Ottokar personally led the main Imperial Army in Bohemia south in the hopes of defeating Hugh the Heir completely. He managed to invade west in the Burgraviate of Nuremberg and send Hugh on the run, linking up with the remaining army of Bamberg. As a result the Imperial City of Nuremberg would surrender, fearing another difficult siege.

In Hugh’s defeat the Thuringian enclaves in Wurzburg would also be captured, leading to the St. Zoe Massacre in May against the local population, perpetrated by the leaders of Bamberg. After the surrender of Weissenburg, the Emperor entered the city in triumph, but he would soon realize he had been lured into a trap, as an enemy army had been hidden within the city by Hugh to catch the Bohemian leaders off guard upon entry. That night the Emperor was attacked and his Imperial Guards attempted to fight off the attackers. Jaromir Přemyslid, the Premier Captain and the Emperor’s brother, was killed while defending the Emperor. As a result the soldiers managed to capture the Emperor alive and take him to Hugh, where they delivered humiliating terms to the Imperialists. The Bohemian army was effectively made to withdraw, although the Duke of Livonia refused to stand down, and continued fighting near the border. An enormous ransom was demanded, with the Emperor paying a large amount immediately to spare his life. Due to the lack of funds, the Emperor’s mercenaries under the Englishman John Hawkwood deserted and turned on the Bohemians, managing to secure the area west of Bohemia proper. Hawkwood declared himself the Count of Bayreuth and launched an invasion of Bohemia. Amused at this method of weakening his enemy, Hugh recognized the state in exchange for a conversion to Jungism from Hawkwood.

Soon after, Duke George would march on southern Bavaria hoping to decisively defeat the rebellion of Kaspar von Schmid. In the south the Bavarians managed to largely secure their country, but were stopped from taking Passau or Salzburg by the Austrians who dealt them a decisive defeat. The battle turned to the Austrians' favor after the arrival of Bartolomeo d'Alviano and the White Company, the same company of mercenaries that the Emperor's late brother once commanded, establishing the company as the premier mercenaries of Europe. Now in exile and unpopular to the point of possessing hardly any Bavarian allies, Kaspar von Schmid would send a peace offer to Bavaria.

The Imperial situation seems to be dire, with the capture of the Emperor by the Jungists. This leads to the situation within Bohemia itself deteriorating at first, as a minor rebellion breaks out. With support from the Jungists abroad, the non-Catholic population of Bohemia rallies behind a rival king: Charles I of Brandenburg. Charles would never actually act upon this claim personally, but throughout Bohemia a movement persisted in 1512 to have him declared King, which the Duke of Livonia and Ottokar’s children fought to combat. His second son Jan becomes known as Jan “the Swimmer”, after he was thrown off his horse into a river while in battle, but managed to swim for a mile downstream and regroup with retreating soldiers, returning to win the day. As regent, Pavel "the Samaritan" helped to negotiate a peace. First he ordered a withdrawal from Bavaria and tried to arrange for peace in which George would be recognized as Duke, as long as he withdrew from Salzburg, Passau, and any lands that were still in the hands of the Catholic allies. The Duke of Livonia managed to achieve a crucial victory over the Taborites at the Battle of Aussig, in which several thousand rebels were killed, while Livonia’s army only lost a few hundred men. As such, Pavel was able to negotiate a peace in which Charles disavows claim to the Kingdom of Bohemia, effectively ending the revolt. Under the Duke’s guidance, the inquisition began again in full earnest, targeting both Jungists and Taborites.

While the Emperor was in captivity, Duke Edmund Alwin of Saxony would write to him and advise that he be treated well by his captors. Meanwhile another Saxon, Bishop Gustav Jung, would travel to the Emperor personally to attempt to bargain a deal—the Emperor’s release in exchange for a concession of land to Saxony and religious freedom for Jungists. Soon after, while the Emperor was being brought north, a daring rescue attempt would be launched by Jantis "the Jackal" Jett and several other imperial guard. Jantis managed to sneak into the Jungist camp and impersonate an officer, allowing him to free the Emperor. In the escape, Ernest Frederick would be killed in battle, but the rest of the men managed to escape with the Emperor. Jantis would be awarded the Iron Cross and become the Premier Captain for his bravery.

When the Emperor returned to Bohemia he would be furious, and ordered retaliation. Imperial forces sacked Weissenburg in a controversial move, with the leadership of the city being captured and tortured. Hawkwood converted back to Catholicism and tried to switch sides, defeating several smaller states to show his dedication, but the Emperor invaded his domain anyway and managed to kill Hawkwood in battle. Following the Emperor's escape, Gustav Jung went into hiding to avoid the Emperor’s wrath, and steveltrender Theoderic Rood became acting Bishop of Saxony. A request from the Kingdom of Lotharingia, in which the Emperor would condone Lotharingian invasions of nearby states, would be vehemently rejected by Emperor Ottokar, and also cause a complete falling out between the German states and Lotharingia, with John VI of Lotharingia later known as “The Terrible”.

After the death of Hawkwood, the English state of Bayreuth seemed in a tentative position, but Hugh the Heir decided to prop the state up and moved his forces in to prevent its complete collapse. He first proposed that Hawkwood’s lieutenant and brother-in-law named Robert Gerard be crowned Count, and moved forces from Nuremberg to aid him. The Englishmen of the group continued to maurade and conquer various lands, often to the dismay of both sides. Hugh also secured himself to the family, marrying several of his relatives to the Bayreuthers. In the summer of 1512 he invaded the Palatine hoping to dislodge their territory there before peace could be made. Within the year the Diet of Hall would be held, which formally ended the war in Bavaria, confirming George as duke.

Knights’ Revolt

In March 1512, with the war in Bavaria ongoing, a knight and former commander of the Imperialists, Franz von Sickingen, began a radical revolt in Swabia to overthrow the princes of the region. Inspired by Jungism, he called for the abolition of the princes, the unification of Germany and the secularization of church principalities, and a "nobleman's democracy". He managed to defeat a Catholic army to secure several towns in eastern Swabia, but then also turned on the Jungist Count of Hohenzollern as well, taking that city. The besieged city of Ulm elected him their leader in the hopes it would motivate him to help relieve the city. Instead he marched in the other direction, intending to capture the Bishopric of Strasbourg and other cities beyond that.

Jungist states such as the Messin Republic would initially be supportive of Franz von Sickingen, as Metz was in the process of consolidating control over the surrounding bishopric, but even these states eventually were at odds with him. One of the leaders of the Catholic expedition to Bavaria, the Duchy of Habsburg, would become the lead force against Sickingen, seeking to recapture the lands he seized from the Archbishopric of Mainz and others. However, as the war with Bavaria was ending, the Habsburgs would attempt to align with Sickingen in exchange for the lands of the Bishopric of Strasburg in a negotiated peace.The Duke would allege that the Bishop had been greatly abusive and responsible for the many failures the Catholic side had suffered. With the distraction of Bavaria ending, Sickingen hoped to ensure a favorable outcome that allowed him to remain partially in power. To Bavaria, he offered to order, if not aid, in the surrender of Ulm, in exchange for recognition as ruler of it, as a vassal of Bavaria. To the rest of his adversaries, he offered to cede a large amount of territory, in exchange for the position of Hegemon of the Swabian League.

Around the same time the Duchy of Habsburg had begun to make inroads into Swabia, seeking to take advantage of the relative chaos ongoing in the region. The Habsburgs made multiple attempts to purchase territories and estates belonging to the Archbishopric of Mainz, as the Archbishop began raising funds to fight the reformation; many of these lands were later raided or conquered by Sickingen. At the same time the Habsburgs raised their own forces to lead the opposition to the Knights' Revolt, contributing to a disasterous battle near Ulm in the beginning of the year. After Sickingen's advances against Strasbourg began – a city that the Habsburgs notoriously feuded with themselves – Duke Leopold II changed his strategy, offering to negotiate with Sickingen and recognize part of his conquests, in exchange for Habsburg lands being spared. Based on the famous addage of “Let others wage war, you, O happy Habsburg, marry" a marriage proposal was offered in which Franz von Sickingen would marry Leopold II's sister Anne, which took place in late 1512. All the while Leopold II negotiated with powerful archbishoprics such as Mainz and Trier, hoping to legitimize what would become a controversial alliance, while the Bishop of Strausborg was painted as corrupt, in the hopes that the Habsburgs might be allowed to claim the bishopric for themselves.

Franz von Sickingen continued his conquests into 1513, taking the Bishopric of Strausborg and besieging the city of Ulm. His unholy alliance with the Habsburgs led to him claiming the title of "Hegedmon of the Swabian League", making him a de facto head of the many small territories of Swabia. This prompted the creation of the Alsace League and an alliance between Vaudemont, Blamont, Salm, Toul (both the city and the bishopric, Strausborg (the city), and Trier to combat Sickingen's advances. After a series of careful negotiations the Alsace League and Sickinge's Swabia would agree to an uneasy peace in mid 1513, while Sickingen went to war against the Swiss Confederacy. Around the same time the Duchy of Habsburg secured the vassalage of the former lands of the Bishopric of Strausborg, and also bought the remaining lands in Swabia that the Archbishopric of Mainz possessed (now at a greatly reduced rate), in exchange for Habsburg support to the counter-reformation. The working relationship between the Habsburgs and Sickingen quickly broke down, especially due to Sickingen's refusal to heed the advice of Leopold II and retire while he was ahead, as he now led a war against the Swiss Confederacy.

As a result, in late 1513 the Habsburgs renegged secretly on their alliance with Franz von Sickingen. Negotiations began with the Holy Roman Emperor Ottokar I, who although distracted by conflict elsewhere was monitoring the situation and making preparations to move against Sickingen and Jungists in Swabia. Leopold II would negotiate to break his ties to Sickingen, switch sides in the war, and lead a costly inquisition against the Swabians, in exchange for the title of Hegemon of the Swabian League for himself, as well as the confirmation of the territories the Habsburgs had taken themselves. In desperate need of funds and support for the counter reformation, the Archbishop of Mainz urged the creation of such a treaty. As a result the Habsburgs also were entered into the Alsace League as a member, further assauging fears of further Habsburger aggression in Alsace.

For the Sickingen the war quickly deteriorated afted that. By early 1514 he had lost a large portion of his army to attrition, raids, and desertions while near the Swiss border, making his control over Swabia tentative and his capabilities greatly limited. He would ultimately die when struck by a cannonball near the Swiss border, marking the end to his rebellion and seemingly his radical beliefs on governnance. For the Duchy of Habsburg's late stage involvement in defeating Sickingen in battle, the Bishopric of Strausborg was confirmed as a vassal of the Habsburgs, with personal property of the last bishop being returned, and a formal ceremony taking place in the city of Strausborg itself. The Habsburgs would also become a leader of the counter reformation in Swabia, laying the foundation for their later involvement in the Catholic League toward the end of the century, however, their military build up and expansion of influence into Alsace and Swabia alarmed the Kingdom of Lotharingia, leading to a build up of tensions that would not formally resolve until the Amiens War a few decades later.