Europe (Merveilles des Morte)

Europe is a continent which is located entirely in the Northern Hemisphere and mostly in the Eastern Hemisphere. Europe is also recognized as part of Eurasia, and encompasses the westernmost peninsulas of the continental landmass. It is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the west by the Atlantic Ocean, to the south by the Mediterranean Sea, and by Asia to the east. Despite this connection over land, Europe is almost always recognized as a separate continent due to its impactful history and traditions. The continent is commonly considered separated from Asia by the watershed of the Ural Mountains, the Ural River, the Caspian Sea, the Greater Caucasus, the Black Sea, and the waterways of the Turkish Straits. Europe covers about 10.18 million km2 (3.93 million sq mi), or 2% of the Earth's surface (6.8% of land area), making it the second-smallest continent, when using the seven-continent model.

European culture is considered the root of Western civilization, which traces its origins to Ancient Greece and Ancient Rome. Europe's ancient history came to an end with the Fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476 AD and the subsequent Migration Period, beginning the Middle Ages. Beginning around the start of the 16th-century, Europe's modern era began with the Renaissance and the Age of Discovery. European powers have since played a predominant role in global affairs, leading the colonization of the New World and much of the globe.

History

Early Modern Period

The early modern period began around 1400-1500, following the Middle Ages, and lasted until about 1800. It is variously demarcated by historians beginning with the Renaissance period in Europe, the Age of Discovery (especially the voyages of Kolumbus and Sommer which opened the New World to Europe), or the end of the Crusades. The early modern period is characterized by the rise of a globalizing character; new economies and institutions emerged, becoming globally articulated over the course of the period.

Gunpowder Warfare

By 1500 classic feudalism in Western Europe had effectively ended. Beginning with the Hundred Years' War, and solidifying especially in the early 16th-century, the reliance on militaries created by the nobility in favor of professional fighters ended the nobility's claim on power in much of the continent. This would begin a process of centralization of most European states and the adoption of professional fighting forces, making the mercenary forces of the Middle Ages obsolete. However, this would be a gradual process, with most soldiers of the Forty Years' War being mercenaries; that conflict cemented the need for better disciplined and ideologically united soldiers. With the expansion of the military came the expansion of organized bureaucracies to manage these armies, which historians argue is the basis of the modern state. Corresponding with these changes came a number of geopolitical alignments and wars across the continent. The size and scale of warfare dramatically increased, as did its devastation, and the adoption of gunpowder weaponry became widespread. After 1500, rapid advancements in fortifications were made, with medieval castles being replaced with polygonal fortresses in response to the development of explosive shells, and siege warfare became increasingly common and ferocious.

At the onset of the modern period, central Europe remained dominated by the Holy Roman Empire, an increasingly decentralized patchwork of hundreds of states, all loosely under the authority of the Holy Roman Emperor. Through intrigue and political maneuvering, the House of Lenzburg emerged as one of the dominant dynasties of the empire, contributing to the fall of their rivals the Habsburgs and the consolidation of the Swiss Confederacy. Their rise to power would lead to conflict with the resurgent Přemyslid dynasty of Bohemia, culminating in the Lenzburg-Premyslid War. The success of the Bohemian faction under Henry VIII reversed the fortunes of the Lenzburgs and allowed the Přemyslids near uninterrupted ascendency to the imperial throne. Due to their mutual rivalry with the Swiss and their allies, Bohemia aligned with France under William II, who spearheaded the modernization of France and its military, later inspiring the rest of Europe to undergo military reforms.

The rise of France catalyzed the creation of a frequent defensive alliance of Spain and Lotharingia, effectively surrounding France and forcing it to look to German states as a counterbalance. In 1470 John IV of Lotharingia ascended to the Spanish throne through his marriage to Catherine of Spain, placing the two states in opposition to France concretely. Concurrently, France's historical struggle with the Papacy in regards to the papal authority within France's borders, as well as the political fallout from the Lenzburg conflict and William II's personal rivalries with religion, laid the foundation for France's protestantization following the Reformation. After William II's death in 1517, the Přemyslids ascended to the French throne, solidifying the Přemyslid-Luxemburg Rivalry that would come to dominate central European geopolitics.

France and Bohemia would briefly unite under Jaromir, Holy Roman Emperor (r. 1517-1544), after which France remained ruled by his descendants for the next century, a situation that occasionally sparked disagreements within the dynasty. The rivalry against the Luxembourgs largely played out in Italy, where a century-long series of conflicts known as the Italian Wars developed, and in the Lowlands, where religious and political differences between north and south Lotharingia began the Dutch Hundred Years' War and the dissolution of Lotharingia into Belgica and the United Kingdom. A religious-based succession crisis in England led to the ascension of a Luxembourg king in England, placing the nation in personal union with the United Kingdom after the Anglo-Danish War of 1592-1600.

Religious conflict fueled European affairs for the next century, in what became the European Wars of Religion. Using the vast wealth it had acquired from the New World and its global empire, Spain became the leading defender of Catholicism and the instigator of widespread counterreformation. At the head of the protestant cause arose the Rätian Union, a radical republican confederacy with Thinwhitedukism and Jungism as guiding principles. Bohemia's untenable obligations to align with France, an increasingly Protestant and expansionary power after the Amiens War, catalyzed an imperial civil war during the reign of Henry X, who became the empire's first Jungist emperor. Under his successor Charles V, a tenuous religious compromise emerged in the Holy Roman Empire, which ended with the Forty Years' War in 1595.

Age of Discovery

In 1491 the voyage of Kolumbus and Sommer, in the service of the Hanseatic League, ushered in the beginning of widespread colonization of the western hemisphere by European powers. In 1522 the first circumnavigation of the globe would be completed by the Portuguese, and soon after Portugal, Spain, the Hansa, England, France. and others became on the forefront of establishing global empires in the New World, Asia, Africa, and Oceania. Spain would emerge as the most successful of the European powers in the Western Hemisphere, establishing a rich empire stretching from Meridia to central Kolumbia, which it used to finance its wars across the European continent.

In Kolumbia, indigenous peoples had built large and varied civilizations, including the Tarascan Empire in Mesoamerica, and the various empires of Oasisamerica further north. In northern Kolumbia, a complex relationship of states had formed under the influence of Vinland, and with the introduction of European contact, the northeast became the center of the transatlantic beaver trade. This fueled the growth of indigenous powers such as the Iroquois, Wabanaki, and Shawnee, and began the devastating Beaver Wars, which transformed Kolumbian society. The conflict would be catalyzed by the settlement of the St. Naðún River valley by the Celtic Union, who founded the colony of Nova Scotia. Settlement on the southern end of the eastern seaboard was spearheaded by the Hansa, who founded the colony of Carolingia in 1533.

Protestant Reformation

In 1504 German cleric Konrad Jung published a list of grievances he had with the Catholic Church. Although initially not intending for such a thing, this led to a complete break from Catholicism by Jung and his followers, leading to the creation of new sects of Christianity. Jung would be joined by such reformers as Franz Kafka, the father of the Reformed branch. With the development of the printing press in Europe, these new ideas spread throughout the continent, causing widespread adoption of non-Catholic movements. These religious divisions would bring about a wave of religious wars, which devastated the continent.

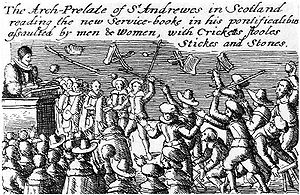

The reformation had its roots in numerous pre-reformation religious movements which challenged papal authority, and grew due to the church's widespread corruption at the end of the Middle Ages. Thuringia, the birthplace of Jung, was prior to him a center of Adamite teaching and religious discussion spurred on by the eccentric Thin White Duke. Relations with the papacy were further soured by the Henrician Civil War (1494-1495), which took up a religious angle. As a result, Thuringia would become the first state to openly convert to Jungism, and alongside Brandenburg and Saxony would create the first Protestant alliance, which gained success in early religious conflicts. Jung's premature death in 1507 caused the protestant movement to fracture and radicalize, leading to the Great Peasants' War in the 1510s and numerous, more radical religious moments. In 1534 the Rätian Union would be founded with Thuringia at its center, as a radical Jungist confederacy, and this state would lead the protestant cause against Bohemia and other Catholic German states prior to Jungism's formal legalization.

Controversies during the counterreformation would lead to the Kerpen War (1541-1547) in northwest Germany, which contributed to the protestantization of the Hanseatic League and the creation of the Northern Catholic Church, a schismatic Catholic group centered in Bremen. Following an imperial civil war led by antiking Leopold II of Habsburg, the conclusion of the War of the Three Henrys in 1563 led to Henry X becoming the first Jungist emperor. In response to the growth of the protestant movement, the Catholic League would be formed which successfully toppled the protestant electorate in Trier through the Trier War (1566-1574). The Catholic League would become highly influential in the imperial election of 1560, allowing the election of Charles V.

In northern Europe, the reformation led to the rise of Denmark-Norway under the House of La Marck and the Kingdom of Sweden, two rival protestant leaders. Under Joan, France likewise embraced the reformation through Gallicanism. Religious differences destabilized the British Isles, with Catholic Scotland fighting to retain control over an emergingly protestant Ireland.

Forty Years' War

The Forty Years' War, fought between 1595 and 1636, would involve most of the nations of Europe and become the largest war in European history until the 20th century. Beginning as a religious war in the Holy Roman Empire, the conflict quickly expanded to non-religious alliances. The cause of the war came with the Imperial Elections of 1595-96 following the death of Charles V, when a deadlocked imperial election escalated into full scale war in and around the city of Frankfurt. The election of two rival emperors took place: Frederick V representing Catholics and Joktan representing Jungists.

The conflict saw widespread devastation of central Europe and its local populations, caused by the practices of foraging mercenary armies. Widespread famine and disease caused the destruction of much of the Holy Roman Empire and surrounding areas, and bankrupted the major nations of Europe. Between one-fourth and one-third of the German population perished from direct military causes or from disease and starvation. With the peace of 1636, religious wars in Europe largely came to a close, with nations deciding their own religious allegiance. In the majority of the continent, absolutism became the norm, as power further centralized around powerful monarchs.

General Crisis

The period stretching throughout most of the 17th century and into the early 18th century is often known as the General Crisis by historians, for its seemingly high concentration of global conflict and widespread instability. This theory largely focuses on Europe, where the continent experienced its worse conflict in its history by number of casualties up to that point – the Forty Years' War – as well as numerous other localized, but highly deadly smaller wars, such as the Celtic Civil Wars, The Fronde in France, rebellions across the various continental possessions of the Spanish Empire and other continental powers, and the Time of Troubles in Eastern Europe. According to 19th century historian Marcus Hobbes, the middle years of the 17th century in Western Europe saw a widespread breakdown in politics, economics and society caused by a complex series of demographic religious, economic and political problems. Hobbes defined this conflict as being rooted in the conflict between "court and country"; that is to say between the emerging centralized, bureaucratic, sovereign states represented by the court, and the traditional, decentralized, and land-based aristocracy and gentry that represented the country. To Hobbes, the intellectual and religious changes brought about by the Renaissance and the Protestant Reformation laid the foundation for the general crisis; the foundation of the modern nation state in the aftermath of the Forty Years' War necessitated "violent socio-economic struggles and profound shifts in religious and intellectual values".

Other historians point to economic factors in contributing to the General Crisis. According to historian Thomas Parker, the 17th century was a "a necessary phase of economic crisis required by the progress of modernity". Parker pointed to such examples as the Kipper und Wipper crisis, which saw the breakdown of effective taxation, the debasement of currency, and the diminishing of trade in Central Europe during the middle half of the century. The shift of European states toward mercantilism, credited with developing the concepts of modern capitalism, is often cited as a turbulent aspect of the General Crisis. However, critics of the General Crisis theory often point to the success of the Lowlands during the Belgian Golden Age as a time of economic expansion, contrary to the thesis of a widespread economic crisis. Other factors often cited include the effects of global climate change; the onset of the Little Ice Age, in which much of the world, especially the North Atlantic region, experienced pronounced cooling. This led to poor harvests throughout much of the century, leading to famine and war. From approximately 1645 until 1715 the Maunder Minimum occurred in which sunspots were exceedingly rare. Several abnormally large volcanic eruptions during the period are also credited with having profound impact on the global climate.

Age of Absolutism

The absolute rule of powerful monarchs such as John VI of Spain (1610–1661) produced powerful, centralized states, along with large armies and powerful bureaucracies led by the monarch, sparking conflict with traditional institutions such as the churches, legislatures, or social elites. Absolutism developed from the rise of professional standing armies, national bureaucracies, the codification of new laws, and the development of ideologies to justify absolutist monarchy—most famously the divine right of kings, a metaphysical framework in which the monarch is pre-ordained to rule. The period saw the replacement of the traditional subordinance of Europe's kings to the Pope or emperors, as characterized by the waning influence of the church in the affairs of national government. The successful absolutist states in Europe ended feudal partitioning in favor of consolidation of the monarch and the state's power, and fought to curtail the influence of powerful nobility and subnational entities.

Conversely, states such as France failed to solidify absolute rule behind a monarchy. Instability in the aftermath of the Forty Years' War led to The Fronde, a decisive victory for proponents of a constitutional system. In 1682 the French monarch would be completely overthrown, beginning a French republic known as The Secretariat.