Religion (Merveilles des Morte)

Religion is a system of beliefs and practices that are based on personal faith, or a corporate tradition comprising a religious community. It can consist of rituals or personal moral obligations (orthopraxis), or require subscription to a specific theological or cosmological model (orthodoxy). These beliefs can be either derived from esoteric experiences of the natural world (General Revelation), or passed down from a spiritual, a metaphysical experience (Special Revelation). Many religions revolve around the worship of a God, or group of gods, which exist separate from the physical world to one degree or another. However, there are religions that believe in non-sentient spiritual forces in the universe, or no spirituality at all.

Religion can often play a fundamental role in defining the personal identity of an individual, as well as an ideological foundation for the development and growth of a civilization. For this reason, religion is often used as a defining trait for ethnic communities, along with other common features such as language, genetics, or national heritage.

The vast majority of religious adherents fall under Abrahamic Religions, which all derive their ancestry from the ancient patriarch Abraham. Abrahamic religions mostly consist of sects from Christianity, Islam, or Judaism. The largest and most widespread religion in the world is Christianity, followed by Islam. Both of these religions have billions of adherents across multiple continent, but are also divided into smaller sects that disagree on fundamental beliefs related to theology, soteriology, or ecclesiology. Christianity and Islam, along with Buddhism in India, are also known as evangelical religions, as all three encourage proselytization of orthodoxy that transcends local cultures and languages. Most other religions focus on a single ethnic group, language, or cultural heritage to comprise their adherents, and do not encourage proselytizing to other cultures. These ethnic religions, indigenous to the continents of Europe, Africa, or the New World, are collectively referred to as "Pagan" by the Abrahamic faiths.

Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic, monotheistic religion based around the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth, also known as Jesus Christ (c. 4 BC – 30/33 AD). Its name derives from Greek term "little Christ", first attested in the 40s AD by Greek-speaking Jews in Antioch. Christianity is the largest and most widespread to religion in the world, consisting of over two billion followers across all continents, and the majority religion in over 170 countries.

Christianity believes in a trinitarian theology, in which the single Godhead is divided into three distinct persons: the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit. Jesus is believed to be the physical manifestation of God the Son, making him the literal incarnation of God. Christianity believes that the world was created by God in a state of perfection, but became tainted with sin and death by the result of humanity's faithlessness and their decision to commit sin and disobey God. Rather than judging the world for its corruption, Jesus sacrificed his own life and took humanity's place to receive punishment from the Father, a doctrine known as transubstantiation. Christianity believes that Jesus spent three days in Hell after his crucifixion, and ultimately rose from the dead in an event remembered as Easter Sunday. By placing their faith in Jesus' sacrifice to forgive their sins, Christians expect to achieve salvation and immortality after death, imitating the Resurrection of Christ.

Christianity began with the disciples of Jesus in 33 AD, and quickly spread throughout the Roman Empire and many neighboring nations over the next few centuries. By the end of the Middle Ages, Christianity had become the dominate religion across Europe, and from there was spread by missionaries and colonization across the New World, Africa and Asia. By that point, however, Christianity had gradually splintered into various sects and denominations, each of which interpret the theology or organization of the Church in different ways. Christianity bases its teachings on the Christian Bible, consisting of Old and New Testaments collected across writings of Ancient Judaism and the early Church. The Bible is believed to be the inspired Word of God, but the exact canon and translation of the Bible differs between different Christian denominations.

Catholicism

The Roman Catholic Church is the largest and most widespread denomination of Christianity, consisting of over one billion adherents worldwide. Its name comes from the Latin term "Catholic" meaning "Universal". The Catholic Church believes that governance and interpretation of Christianity was entrusted to the Apostles, led by the "chief" Apostle Simon Peter (c.5-67 AD). This same authority was passed to the successors of the Apostles down the centuries, known as the Early Church Fathers, and the body of their writings and traditions are collectively known as Catholic Dogma.

Catholicism believes that the Bishop of Rome is the direct successor of Simon Peter, and consequently the Church in Rome is the central, hierarchal authority over all Christianity. Catholicism strongly adheres to a rigid hierarchal system of governance, in which local Churches are overseen by a Bishop which is assigned to a regional diocese. These Bishops derive their authority from an Archbishop that represents an archdiocese. The highest authority is the Bishop of Rome, also known as the Pope, whose decisions are considered to be infallible as inherited from the Apostle Peter.

German Catholic Church (Callixtine)

The German Catholic Church, also known as the Callixtine Church or the Hussite Catholic Church, is a Catholic rite held by a minority population in the Holy Roman Empire, mostly found in the Crown lands of the Premyslid Dynasty. It is a sui iuris Patriarchate in full communion with the Catholic Church, unlike their schismatic counterparts (the Northern Catholic Church and the independent Hussite Moravian Church). It holds its ecumenical seat in the Cathedral of Saint Lawrence in Prague, and its Patriarch is appointed directly by the Pope in Rome. Just like the Celtic Church, the German Church submits its clergy to the inspection of the Ecclesiastical Tribunal from the Roman Catholic inquisition.

The German Church is distinguished from Catholicism by the Four Articles of Prague that were adopted in 1430 at the Ecumenical Council of Rome, which was supported at the time by Jan Hus. The German Church conducts their services in the Czech vernacular. They permit preaching and instruction of the gospel by all Christians, both priests and laymen. The Eucharist of the German Church is given in both kinds, bread and wine, to both priests and laymen. Finally, the German Church has a strict adherence to fair judgement in the Church, which applies the same ecclesiastical discipline regardless of title or social status. Just like with the Celtic Church, the German Church allows married men to become consecrated as priests, but does not permit priests to become married, and only celibate priests may be elevated to Bishops.

The German Catholic Church was first conceived at the Ecumenical Council of Prague, which lasted from 1411-1415. This council was marred by the complex political climate, particularly the dispute between Emperor Vincent and Pope Benedict XI which culminated in the Marcian Schism. Partly as a result of this political division, the council split the disciples of Jan Hus between the moderates willing to reconcile with the Pope (Callixtines), and those who sought to abolish the Papacy altogether (Taborites). Jan Hus himself was mostly neutral in the rest of his life after the council, but he generally favored a peaceful resolution with Rome and condemned the violence of the Taborites.

Jacob of Mies was made the first Hussite Patriarch in 1418, around the same time the Taborites migrated to Lothringia at the invitation of Antipope Mark II. The organization of the Hussite Church was fully resolved at the Council of Rome in 1429, and remained the same until the Protestant Reformation. The authority of the German Church suffered greatly during the Wars of Religion in Europe, as a result of the Zephyrinite schism known as the "Northern Catholic Church". However, the Counter-Reformation led by the Premyslid Dynasty helped to establish the German rite within their own territories.

Northern Catholic Church

The Northern Catholic Church, also known as the German Catholic Church or Zephyrinites, was a schismatic Catholic Church not in communion with the Church in Rome. Its seat was held in the city of Bremen, and was led by a Pope who traces his succession from the election of Jean Ferrier, also known as Antipope Zephyrinus II, in 1545. The structure of the Northern Catholic Church was largely borrowed from the Callixtine Church, but also imitated the Roman system of Cardinal-electors that met in the city of Bremen.

During the Reformation of the 16th century, many churches felt disillusioned by the Pope's inability to suppress the Jungist movement. Many bishops and theologians argued that the sui iuris approach of the Catholic Church had become far too liberal, and the current issues of the Protestant Reformation was the result of the Church comprising too heavily in favor of heresies. The Gunpowder Plot of 1535 polarized Catholic leadership, and led to a rise in popularity of reactionaries within the church, in what became known as the Spirituali-Zelanti split. Beginning with the reign of Francis I (1534-1540), the Zelanti faction gained preeminence in Rome, beginning a harsh round of inquisition, including against claimed Primate of Germany Martin Breuer. In 1541 the head of the Teutonic Order, Henry von Kerpen, seized the initiative to begin a militant suppression of Jungist communities in northwest Germany, in what became known as the Kerpen War. Becoming increasingly puritanical and radical in his pursuit, Kerpen subsequently attacked both Catholic and Jungist states alike, leading German states to call for condemnation from the Pope; Paschal III instead supported Kerpen, leading to a schism among German churches.

Although not usually reasons to discount a papal election, these bishops nonetheless considered the incumbent Pope Paschal III to be illegitimate, and called a new conclave of cardinals in the city of Hamburg. This new conclave elected Archbishop Jean Ferrier in 1545, adopting the name Pope Zephyrinus II. The name of Zephyrinus is a puzzle to some historians, as the original Pope Zephyrinus from the second century AD had a rather ignominious, if not infamous papacy, yet Jean Ferrier never left any writings to explain his rationale. At any rate, this movement of German Catholics split away from the synod of Callixtine Catholics in Prague, leaving the latter in a much weaker position in Central Europe.

At its height, the Zephyrinites had recognition from bishops from across Germany, Bohemia, Poland, and Arles-Burgundy. Antipope Zephyrinus II accepted this recognition along with numerous other Holy Orders, which he used for the purpose of the ongoing Counter-Reformation, as the intention of the Zephyrinites was never for combatting the Church of Rome, but rather their focus was on the elimination of Jungism across Europe. After Pope Paschal III died in 1547, the Cardinals in Rome entered into negotiations with Ferrier with regards to the Counter-Reformation, and left the seat in Rome vacant for the time being. The Zephyrinite movement significantly fell out of favor when Ferrier died in 1550, and the Jesuit leader Francis Xavier was elected as Pope Leo XII.

Celtic Catholic Church

The Celtic Catholic Church is the authorized rite of the Catholic Church used by nations in and around the Celtic Union. It is a sui iuris Patriarchate in full communion with the Catholic Church, with its seat located on the Isle of Mann in the British Isles. It is currently recognized by the governments of Ireland, Scotland, Wales, Iceland, and Greenland, with minority communities also located in England, France, and Norway. While recognized as part of the same universal church, the Celtic Patriarch is elected from Elector-Bishops rather than appointed.

The Celtic Church allows for married men to be consecrated as priests. However, an unmarried priest must remain unmarried, and only celibate priests may be appointed as Bishops. The Celtic Church also conducts their services in one of two languages: Middle English or Gaelic. A Gaelic translation of the Bible was authorized in 1371 by the Pope, and used in the Celtic Church for their services. The Celtic Church considers capital punishment a sin, and has outlawed the practice by the decree of Patriarch Hilmar in 1407. This has had a profound impact on the history of human rights within the British Isles.

Upon the death of the Celtic Patriarch, a college of Elector-Bishops are assembled in the Isle of Mann to elect his successor. There are usually a total of six Elector-Bishops, originating from the nations of Scotland, Wales, Ireland, and Iceland, as well as the dioceses of Mann and Cornwall. The first Celtic Patriarch was Hilmar Gunnarsson from Iceland, universally recognized as the greatest and most dynamic Patriarch, although he was appointed by Pope Clement VI and not elected. The first election of the Celtic See was held in 1414. A Latin-rite Archbishop also exists on the Isle of Mann, as many Catholics in the Celtic Union also follow the Roman Catholic religion, but these two institutions are strictly separated. The Ecclesiastical Tribunal, a branch of the Roman Catholic inquisition, also has jurisdiction over the bishops of the Celtic Church.

The Celtic Church was first created at the Ecumenical Council of York, also known as the Council of the Earthquake, which was held from 1380-1383. This was largely an attempt by the Catholic Church to reconcile the Protestant movement by John Wycliffe, also known as Lollardy, which had originated in London and quickly spread into Scotland, Iceland and Norway. Wycliffe himself never reconciled with the Celtic Church, and died in prison shortly after the council concluded. The original conclusions of the Council intended to create a second sui iuris Patriarchate for the Kingdom of England, called the "Anglican Catholic Church", but this was universally ignored by the English nobility.

However, the ongoing wars in the British isles between the Celtic Union, England and France pushed off the actual organization of the Celtic Church for several more years. In 1388, Archbishop Ari Aranson convinced Queen Guðríður to sever all ties to Rome, and establish Lollardy (officially called "Mótmælandatrú") as Iceland's official religion, in support of the Lollards who refused to recognize the Council of York. This caused Iceland to be excommunicated until 1390, at which point Ari was deposed as Archbishop and replaced by Hilmar Gunnarsson. It was this same Hilmar that finally succeeded to organize the hierarchy of the Celtic Church, and was appointed the first Patriarch in 1393.

Western Catholic Church

The Western Catholic Church, also known as the Basque Church, is a religion held by Catholic Basque people living in northern Spain and south-western France, as well as minority communities in southern Italy. While administrated largely independent from Catholic hierarchy, it is recognized as a sui iuris Patriarchate in full communion with the Roman Catholic Church. It is run by the Western Patriarch, seated at the Cathedral of Santa Maria in Tudela, and appointed directly by the Pope. It was briefly made the official religion of the Kingdom of Navarre and the Kingdom of Sicily, before both of these nations were occupied and annexed into the Crown of Spain. Even so, the Spanish monarchy tolerates and respects the Basque religion as long as it is recognized in Catholicism.

The Western Church conducts its services in the Basque vernacular, instead of either Latin or Spanish like their neighboring Catholic communities. They share most doctrines in common with Catholicism, but hold purity of Church ministers to a high revered level of importance. For this reason, they consider Simony and heretical teaching as the most cardinal sins, based on the passage of James: "Not many of you should become teachers, my brothers, for you know that we who teach will be judged with greater strictness". Acts of nepotism such as Cardinal-nephews are treated as a crime that should be immediately prosecuted.

The original Western Church was formed by Cardinal Federico Goikoetxea as a result of the Iohannan War and subsequent Council of Trier. Federico, along with most Cardinals at the time, felt that Pope John XXI's election was illegitimate due to a public incident of bribery with the Italian Cardinals. This led to the new conclave in Barcelona, which elected Antipope Callixtus IV as the Aragonese candidate. After the Council of Trier elected Pope Gregory XI, King James II of Aragon backed out of the schism to avoid further conflict, and revoked their support for the Spanish Antipope. Outraged and disillusioned, Cardinal Federico returned to Navarre and convinced King Louis "the Quarreler" to revoke all allegiance to Rome, and establish the Western Church in 1314.

The original organization for the Western Church was more radical than the current Patriarchate. Cardinal Federico, adopting the name "Pope Leo X", abolished all conclaves and declared that each leader of the Basque church will personally appoint his successor. The original Western Church also favored secular investiture for certain clerical offices. In 1315, King Frederick III of Sicily also adopted the Western Church and allowed Federico to appoint bishops there. Both of these nations were initially excommunicated by Gregory XI, but after some negotiations Federico was recognized as the first Patriarch of the Basque in 1317. Federico continued as an instrumental minister of the Church up until the conquest of Navarre by Aragon in 1323, at which point he was assassinated.

The Western Church is also notable to have a different list of recognized Popes as the Liber Pontificalis. John XXI is discounted due to his known acts of Simony and corruption, and his pontificate is replaced by the Antipopes Callixtus IV and Leo X. This has had an impact on the numbering system of later Popes, as the later Spanish-born Popes Leo XI and Leo XII continued their regnal numbers where Antipope Leo X left off. The Western Church is also extremely prolific in their missionary works to far-off colonies, especially during the tenure of the Patriarch Francis Xavier, the founder of the Jesuit Order.

Eastern Orthodoxy

The Eastern Orthodox Church is the second-largest Christian Church, and one of the oldest Church denominations alongside Catholicism. Eastern Orthodoxy recognizes an apostolic succession of administration and sacred tradition, similar to the Catholic Church. However, the emphasis of Eastern Orthodoxy centers on unified liturgy and doctrines rather than a strict hierarchy. The Church operates along a series of self-governing religious communities centered at regional metropolitans, known as Patriarchates or autocephalous churches, each of which is governed by a metropolitan Patriarch. Most members of the Orthodox Church are found in Eastern Europe, and practiced as the state religions of Byzantium, Russia, Wallachia, Dacia, and Georgia.

Eastern Orthodoxy recognizes no religious head of the Church, but maintains that Christ alone is head of the Church. While the Patriarch of Constantinople, in apostolic succession from St. Andrew, holds a high degree of respect, he is still the "first among equals" alongside other patriarchates in other Orthodox nations. That being said, the Byzantine Emperor in Constantinople has temporal authority over the Church within the Greek Empire, and holds unilateral power of investiture over all bishops, including the Patriarch himself. In such a way, the Byzantine Empire functionally acts as a theocracy, where the Emperor is both the sovereign monarch of the realm and de-facto head of the Greek Church.

On the outside, the Orthodox Church share many things in common with the Catholic Church: a canon list of saints, a succession of bishops from the Apostles, use of iconography in worship, etc. However, these saints (including the Virgin Mary herself) are not held to a venerated, mystical level that Catholicism does, as that would be considered idolatry. Instead, these icons and relics are symbols that are used in a purely functional capacity. Orthodox icons are tools for completing liturgical rituals passed down by sacred tradition, and are not the object of that veneration.

While the Orthodox Church is decentralized between the different Patriarchs, they maintain a unified doctrine by regular synods between different communities of churches. The Church recognizes the first seven Ecumenical Councils along with western Christianity, but has rarely made any new innovations to doctrine since the time of the Great Schism. The last Ecumenical Council in the east was the Fifth Council of Constantinople, which met sporadically in the 1340s during the midst of the Byzantine Civil War.

The Orthodox Church first began to split from the west in the 9th century AD, when the religious reforms of Patriarch Photius I was condemned by the Pope in Rome, but supported by the Emperor Basil I. In 1054 AD, the Patriarch of Constantinople and Roman Pope mutually excommunicated each other, and remained separate religions ever since. Some attempts were made to reconcile the churches in the 13th century, during the height of the Latin Empire in Greece, but these were not successful.

During the revival of the Latin Empire in the 14th-15th centuries, the Latin states made rigorous attempts to convert the Greek population back to Catholicism. Bishops were forbidden from ordaining married men, in an attempt to align the Orthodox priests with the existing tradition of celibacy embraced by Roman Catholics. Heavy taxes were also imposed by the Latin Empire over Greek-speaking Churches. These suppressive measures is what contributed to the eventual popular uprising that collapsed the Latin Empire in the mid-15th century. In the 1460s, the reunified Byzantine Empire quickly reversed all of these policies.

Starting in the 1480s, the Catholic Church has an agreement with the Byzantine empire to tolerate the Catholicism practiced by the remaining Latin population of Greece, and defers the administration of these religious communities back to Rome. Jewish and Muslim communities are less tolerated, however, and often become subject of suppression across the empire.

Within the community of each Patriarchate, the Orthodox Church holds religious services in the local vernacular. For this reason, the Church has no strict regulation on Bible translations as in the west. The "Dacian Bible" was first translated in the 1330s in the Principality of Wallachia, which is considered a literary masterpiece of the early Balkan Renaissance.

Georgian Orthodox Church

The Georgian Orthodox Church is the official religion of the Georgian Empire, and practiced by the majority population in the Caucasus along with minorities across the Middle East. It is an autocephalous Church in full communion with the Greek Orthodox Church in Byzantium, and administrated by the Catholicis-Patriarch in Tbilisi. The Georgian Church traces its origins to the first Christian community in the Caucasus, founded by the Apostle Andrew according to tradition.

The subjugation of Persia and much of the Middle East under the reign of Bagrat V posed significant challenges for the Georgian Church. In order to appeal to the Shia population of Persia, the Emperor portrayed himself as the Occultation of Muhammad Al-Mahdi, the last Grand Imam of Twelver Shi'ism. This multi-faceted image of the Georgian monarch appealed to the liberal population of the empire, but drew sharp criticism from the Orthodox religious elites.

Russian Orthodox Church

The Russian Orthodox Church, also known as the Orthodox Church of all Rus, is the official religion of Russia and also practiced by the Slavic diaspora in various other nations. It is an autocephalous Church in full communion with the Greek Orthodox Church in Byzantium, and shares identical doctrines and practices. It is administrated by the Primate Metropolitan of Novgorod, also known as the Patriarch of All-Rus. Due to Novgorod's paramount political and cultural status in Eastern Europe, the Metropolitan is ranked fifth among the Orthodox Patriarchs, after the four ancient Apostolic seats in the Mediterranean.

The Russian church traces its origin from the Grand Prince Vladimir I of Kiev, also called "Vladimir the Holy", who converted to Christianity in 988 AD. According to legend, Vladimir summoned a council of various religions, including the Catholic and Orthodox, and ultimately came to the conclusion to join the Orthodox Church. This is possibly a fanciful story, as the Great Schism did not come into effect until 1054 AD, and the Catholic Church still appointed Bishops in Russia until the 12th century.

The Orthodox Church continued largely unhindered under the "Mongol Yoke" of the 13th century, up until the Mongol Empire started to collapse in the early 14th century. Originally, the seat of the Russian Church was located in Kiev, but under Mongol rule the center of political and economic power gradually migrated north. During the wars between the Nogai Horde and the Christian states of Poland and Hungary (1295-1298), the Metropolitan Maximus moved the seat from Kiev to Vladimir. When the Mongol Yoke came to an end in 1321, the Metropolitan Peter II moved the seat again from Vladimir to Novgorod. In 1415, the Metropolitan Photius declared the Russian Orthodox Church to be an autocephalous Church under its own Patriarch, which was quickly recognized by the Patriarch in Constantinople.

Oriental Orthodoxy

The Oriental Orthodox Church, also commonly called the Coptic Church, is a branch of Christianity followed by a plurality of population across Egypt, Syria, Armenia, and Eastern Africa. The Coptic Church is organized similarly to Eastern Orthodoxy, recognizing multiple independent autocephalous Churches that are each run by their own ecumenical Patriarch. However, unlike Eastern Orthodox the Coptic Church recognizes a supreme head of all Christianity, which is known as the Pope of Alexandria.

The title of Pope does not have the same autocratic weight as the Pope does over Catholicism, as the word itself derives from a much older meaning. The Pope of Alexandria traces an Apostolic succession from St. Mark, who was the first Bishop of Alexandria. The first Bishop to declare the title of Pope was Heraclius in the third century AD, many years before the Bishop of Rome took the title of Supreme Pontiff. The Pope also holds the title of Patriarch of Africa and the "Thirteenth Apostle".

The Coptic Church believes in Miasyphite Christology. The prevailing position of both Catholicism and Eastern Orthodoxy (as decided at the Council of Chalcedon) is that Jesus Christ is a single person (among the other two persons in the Trinity), consisting of two simultaneous natures that are each human and divine. The Miasyphite position holds that Jesus has only one nature, that is simultaneously human and divine together. It was from this controversy that the Oriental Churches split away from the Church after the Council of Chalcedon in 451 AD. From that point to the present day, the seat of the Coptic Church in Egypt has lived in a constant state of marginalization or persecution by the ruling Egyptian government.

The Coptic Church has a high reverence for monasticism, and as well as an impoverished Christian life in general. The Church in Alexandria was the first Christian community to practice and formalize monastic orders, known collectively as the "Desert Fathers". The Pope of Alexandria is elected, but in a much less formal capacity than the Pope in Rome. The vast majority of Coptic Popes were originally monks before their election.

Ethiopic Orthodox Church

The Ethiopian Orthodox Church is the largest autocephalous denomination of Oriental Orthodoxy, and the official religion of the Ethiopian Empire. It is run by the Metropolitan Patriarch of Axum, appointed by the Ethiopian Emperor in apostolic succession since at least the 4th century AD. It shares all the same organization and theology as the Coptic Church, and recognizes the Pope of Alexandria as the religious head.

Traditions of the Ethiopian Church derives an even longer, somewhat fanciful history of African Christianity dating back to the time of the Old Testament. King Solomon is the mythological progenitor of the Solomonic Dynasty, and supposedly a group of Jews fled to Ethiopia during the Babylonian Captivity, taking the Ark of the Covenant with them. This Ark is housed in the most sacred monastery of the Ethiopian Church, located at the town of Ziwey. According to one Axumite text dating to the 14th century, Alexander the Great learned of Christianity through prophesy, and had himself baptized on his deathbed. It is for this reason that Alexander is unofficially canonized as a Saint in the Ethiopian Church.

The Ethiopian Emperor is considered to be the protector of the Coptic faith, and enforces this duty during their numerous wars with the Mamluk Sultanate. When the Taymiyyah sect of Islam took control of Egypt in the 1330s, the ensuing chaos threatened the very existence of the Church. For this reason, the Pope of Alexandria migrated the apostolic seat to Barari in Ethiopia, in a period of exile lasting from 1349-1362.

Ethiopia has tried evangelizing Coptic Christianity into the Horn of Africa, with limited success. One Somali prince who did convert is highly revered in the Church, now known as Saint Laurentius the Martyr. Laurentius was elevated to a status of privilege by the Emperor, but after a few months his home was destroyed by an uprising of Muslim peasants, who had Laurentius and his family stoned to death. Laurentius' grave is now a shrine for pilgrimage, and later converted to a monastery as the headquarters of the Order of Saint Laurentius.

The second largest monastic order of the Ethiopian Church is the Order of Saint Anthony, established by the Pope in 1349. After the Order of Saint Laurentius was founded in 1408, these two monastic groups quickly collided into a secular and philosophical rivalry. The Emperor Tewodros I settled the dispute by summoning the Ecumenical Council of Barari in 1425, as the first ecumenical council recognized by the Coptic Church in almost one thousand years (since the Council of Ephesus in 431 AD).

Church of the East

The Church of the East, also known as the Nestorian Church, is a community of Christians living in the Middle East and various other parts of Asia. It is headed by the Catholicis-Patriarch of the East, based in the city of Tabriz and tracing an apostolic succession to Saint Thomas (AKA Mar Toma). Unlike Orthodox Churches, the Nestorian church acts as a single unit, with local bishops and Patriarchs that operate in a hierarchal structure back to Tabriz. However, unlike the Catholic Church the Catholicis-Patriarch has only a loose control over these local bishops, and settles disputes using local or general synods.

The Nestorian Church is separate from Western Christianity by having a Nestorian Christology. In a diametric point of view from the Miasyphite Christology in Egypt, Nestorianism holds that the human and divine natures of Jesus Christ consists of two distinct persons. Jesus of Nazareth was only a physical vessel used by the distinctly different Son of God. This doctrine was first proposed by the monk Nestorius (386-450 AD), from whom Nestorianism gets its name. As a result of this belief, Nestorian Churches do not have any iconography of Jesus, or hold veneration for him as a physical, human being.

The Nestorian Church was first organized in 410 AD by the Council of Ctesiphon-Seleucia, and affirmed the Bishop of this same city as their ecumenical Patriarch. Due to the controversy surrounding Nestorius, an Ecumenical Council was called in 431 AD at Ephesus. The Council of Ephesus condemned Nestorianism at heretical, which is agreed by both Catholic, Orthodox, and Coptic Churches, and consequently excommunicated the Church of the East. The apostolic see in Ctesiphon-Seleucia remained under the marginalization or persecution of non-Christian rule for many years, first by the Persian Empire and the Islamic Caliphate. Despite this, Nestorian evangelization efforts continued to be successful through the centuries, slowly establishing permanent communities as far away as India, China, and Japan.

After the Mongol Empire subjugated most of Asia in the 13th century, the Nestorian church flourished both culturally and politically more than it ever had before. The Mongols were tolerant of religion and allowed evangelization to spread across the silk road to every Khanate. For many people in the Middle East, they had felt as if the mythological Prester John had finally arrived to establish his paradisiacal Christian empire. One by one, each of the major Khans of the empire had embraced Christianity themselves, the first the Ilkhanate based in Tabriz (in 1256), then followed by the Nogai Horde (in 1296), and finally the Yuan Dynasty itself (in 1305). Nestorian ministers found the most political power in the reign of Maixu Khan (1294-1318).

This apex of the Nestorian Church quickly fell apart in the 14th century. The Nestorian Crusade (1298-1305) led to the dismantling of the Ilkhanate, and what remnants of the empire remained around Tabriz restored Islamic rule. The collapse of the Yuan Dynasty in the 1310s saw the rise of the ultra-conservative Tian Dynasty, which brutally persecuted the Nestorian Christians that remained. The Catholicis-Patriarch himself moved the apostolic see from Ctesiphon-Seleucia to Tabriz in 1318, where it remains to this day. The Nestorian church has gradually recovered under the restored Christian rule by the Georgian Empire, a nation that is tolerant of all faiths.

Huangdist Christian Church

The Huangdist Christian Church, also known as the Church of China or Church of the Great Horde, was the official religion of the Yuan Dynasty during the last years of the Mongol Empire. It was instituted by Maixu Khan (1265-1318), originally called Temur Khan, after his sudden conversion to Nestorian Christianity between 1300 and 1305. After the Neo-Confucianist restoration by the Tian Dynasty, the Huangdist Church had become effectively extinct, although traditional Nestorian Christianity remained in smaller communities. The official emblem of the religion is distinguished by the imperial yellow color of the Great Horde.

The Huangidst Church was a strictly hierarchal organization, with the Great Khan Maixu as the supreme head of the religion in both name and practice. The Khan held direct power over investiture of Bishops and settlement of theology. He was considered the fulfillment of prophesy in Revelations, being the son of the bridegroom depicted in the 21st chapter. Similar to Chinese Traditional Religion, the Great Khan is granted a Mandate of Heaven from Jesus Christ, who holds the keys of Heaven and Hell. According to the Travels of John Maunderville, Maixu Khan also declared himself to be Supreme Pontiff in 1313, in reaction to hearing about the existing Iohannan Schism. While the Travels are known for gross exaggeration, this is probably a close European equivalent to the Huangdist actual structure.

Maixu Khan made many attempts to encourage conversion to Nestorianism on multiple levels. Many Christian churches were built, both in the cities and the countryside. Some of these churches were converted from Confucianist shrines and temples, having been confiscated or personally owned by the Emperor already. Within the imperial court, immigrant Nestorian ministers from Syria were appointed into high offices, and private military units were formed that were entirely staffed by Christian converts. Maixu Khan implemented a religious bias in the Chinese bureaucracy, in which Christian converts were quickly promoted to higher offices than their Confucianist counterparts. Finally, after Korea revolted in 1304, Maixu ordered Confucianist temples violently torn down and their books publicly burned.

Maixu himself wrote a number of theological essays in an attempt to demonstrate how Christianity could be syncretic with the existing religions of China. The duology of Jesus Christ and the Virgin Mary was identified as the twin deities of the Turko-Mongolic Religion: Tengri and Eje. Mary is additionally identified as Guanyin, the major Boddhivista of Chinese Buddhism. Maixu believed that ancestor-worship in Churches could continue, but recognize these spirits were actually angels and not deified humans. Outside of these theological tenants, Maixu encouraged the rituals of Confucianism to exist side-by-side with the Christian Eucharist. The Confucianist ethical code of family life and social order was believed to be confirmed by the teachings on marriage contained within the New Testament.

It is from this era that we have Huangdist shrines that survive to the present day, depicting oriental figures of Christ and Mary alongside ancient Confucianist icons. Works of artistic calligraphy also survive from this era, which were used as an exercise to translate Christian sayings in Mandarin Chinese. The original Huangdist Church used the Syriac Bible imported from the Middle East, but in 1312 the Empress Atala commissioned the full translation of the New Testament. Converts to the Huangist Church, like the Great Khan himself, were all required to adopt a Christian name translated into Chinese, and reverse the order of their name to fit the western convention.

The Mongol Empire was always tolerant of Nestorian Christianity, and many relatives of the Genghisid Dynasty were Nestorian even before the unification of Mongolia. Kublai Khan, the first of the Mongol Khans to rule China, had a particular interest in Nestorian monks such as the famous Rabban bar Sauma. The Venetian explorer Marco Polo also shared his religion at length in the imperial court. As soon as Temur Khan took power, he summoned Nestorian ministers to deliver theological lectures at court, where he also invited the royal family and numerous court ministers to attend. When Temur Khan campaigned in Central Asia to annex the Chagatai Horde (1298-1302), he took with him a Crucifix emblem for good measure.

After Temur won the Siege of Samarkand in 1300, under the banner of the Nestorian Crucifix, Temur privately decided then to adopt Christianity into China. While this story is what is repeated in the Chinese sources, it is more likely that Temur was influenced by the political situation in the west, which he was informed by embassies at Samarkand that came from the Nogai Horde and the Ilkhanate. Temur had himself and his army baptized at the Zeravshan River, and there constructed the first Huangdist shrine which still exists to this day. After Nestorian ministers were fully embedded into the imperial court over the next few years, Temur Khan officially and publicly baptized the royal family in 1304, adopting his new name of Maixu and declaring the new Huangdist Church to be born. This sudden move was possibly a calculated attempt to wrest power away from the Confucianist bureaucracy, in light of the recent rebellion in Yunnan in 1303.

Maixu Khan focused on expanding Christianity in the northern cities, especially the imperial capital of Beijing. Most Huangdist churches were built there, both for native Chinese population and the Turko-Mongolic immigrants. Evangelism towards the south were much slower, and focused much more on impoverished peasants than the middle class. This came at a cost, however, as the Goryeo Dynasty of Korea broke away from the Empire in 1305, viewing the suppression of their Confucianist way of life as intolerable. Their struggle to fight for independence would continue from that point until the fall of the Mongol Empire. By 1312, the estimated Christian population was about 3 million, and the Church was falling into a shortage of new clergy to minister the growing flock.

After Maixu Khan himself, and his wife Atala, the most important figure of the Huangdist Church is the Blessed Sala of Tongzhou (c.1290-c.1340). Sala was born in Beijing, and adopted Christianity at an early age. She lived a simple life devoid of worldly possessions, carrying only a Syriac Bible and a large wooden cross along her ministry. She was said to convert 10,000s of people in Beijing to Christ, but suffered intense persecution from the Confucianist elite, including an incident of being attacked with boiling water. Sala was eventually granted imperial protection by Maixu Khan, and appointed as a high-ranking minister with a substantial salary. Sala's public three-year ministry, according to tradition, lasted from 1305-1308.

From 1309-1313, Sala of Tongzhou led a small expedition of Nestorian delegates from the court of the Great Horde to Europe, known by western sources as "the Chinese Delegation". The purpose of the delegation was to make pilgrimage to Rome, and establish diplomatic contact with the Catholic Pope. The delegation first passed along the northern silk road through the Golden Horde, before moving through Poland to arrive at Bohemia. From there, they traveled from Bohemia across Germany to Cologne, then crossed the Rhine river into France. One portion of the delegation traveled north to Sweden, and showed off various merchandise of the Far East for the court of King Birger.

In Toulouse, the Chinese delegation heard of the current papal schism between the Pope in Rome (John XXI) and Barcelona (Callixtus IV). Sala wanted to avoid interfering with this controversy, but nonetheless decided to meet with the Antipope in Spain. The delegation passed through Navarre into northern Spain, before arriving at Huesca at the court of Pope Callixtus IV. It was shortly after this meeting that the Council of Trier took place, which initially created a third Pope in the schism. Having been disillusioned at the politics of the Catholic world, Sala took the Chinese delegation back to Beijing, where they arrived in 1313.

During the persecutions of the early Tian Dynasty, Sala worked at smuggling Nestorian converts safely out of the country. She was arrested at Hongzhou in 1331, tortured for a number of months, then sold into slavery in Indonesia. Her life and ministry are mostly recorded by the sacred tradition of the Nestorian Church. During the Georgian Empire, many works of art depicting Sala's ministry were created by Nestorian communities living in Iran.

Early Protestant Movements

Early attempts to depose or split off from the Catholic Church date back centuries before the actual Protestant Reformation by Konrad Jung began, as far back as the Waldanesians and Cathari of the 13th century. These movements usually described the Church as having been corrupted by political influences, and focused on affluence in contradiction to the impoverished, simple lifestyle demonstrated by Jesus and the Apostles. The Cathari held their roots from earlier gnostic sects, and believed the Church to be an evil organization controlled by the Devil.

As the Inquisition was founded in reaction to these sects, the Catholic Church did not hold back in condemning what new movements was perceived to be heresy. When Nogai Khan had briefly claimed to convert to Christianity in order to claim the throne of Poland, Pope Boniface VIII blanketly condemned all the Mongols as heretics. Future Popes after him would continue to condemn the Mongol Khans as "Devils of the Steppes", regardless of their actual religion. Various mystic movements that sought spirituality outside of the Church grew sporadically in the early decades of the 14th century. Some of these were reconciled into the Church as formal monastic Orders, such as the Beguine nuns. Others, however became condemned as heretical movements, such as the Brethren of Free Spirit and the Shepherd's Crusade.

The Iohannan War and subsequent Council of Trier highlighted the direction of future Papal reforms. Along the lines of Pope Boniface's Unum Sanctum, the Church asserted its own sovereignty and distanced itself from influence from secular powers, although the Papacy of Gregory XI unilaterally supported the House of Luxembourg and their rise to power over the Holy Roman Empire. The impoverished clerical movement by William of Ockham led to numerous changes in Catholic administration, both in the Latin rite and the rite of the Western Church.

The Black Death in the late 1340s significantly reshaped the social order of Europe. The reduced population and weakened feudal power led to the rise of a mercantile middle class that paved the way for the Greek and Italian Renaissance. For the Church, the lack of educated priests led to a cognitive dissonance between the Church's doctrine and practice, causing much of the common people to lose faith in the Pope. Many attempts were made to improve education of priests, such as the introduction of Catechism in the 1380s, but this was not completely effective.

Furthermore, the intellectual movement of the Renaissance allowed for many scholars to begin questioning the traditions that Catholicism stood on. The Bible the word of God, and any other tradition that adds to or contradicts the Bible is not from God. This is why Protestantism first took off in regions where middle class education thrived the most, such as Oxford and Prague.

Lollardy

Lollardy or Lollardism was a religious movement founded by the disciples of John Wycliffe (c.1320-1384), and primarily spread across the British Isles, Iceland and Norway. Its name comes from a Middle English term for a simpleton or uneducated person, which was used to describe the movement deridingly. Wycliffe was a trained scholar and theologian from the University of Oxford, and dedicated his study of Christianity from an argument on Biblical passages alone, i.e. the doctrine of sola scriptura. In the 1370s, Wycliffe began publishing works that questioned the need of Catholic sacraments for salvation, as this was not backed up by scripture. Like earlier protestant movements, Wycliffe believed the Church should be impoverished as Jesus and the disciples were, and so his pupils were colloquially called "Poor Priests".

During the upheaval of peasant revolts and civil unrest in England, the Lollard movement spread quickly to other parts of Europe. Archbishop Ari Aranson introduced Lollardy to Iceland in 1378, and King Robert II of Scotland extended a similar invitation in 1379. Among the Italian scholars of the early Renaissance, Alfonso Barque extended his personal support for the doctrine of sola scriptura in 1382, largely inspired from Wycliffe, although the majority opinion in Italy at the time was against it.

Finally, Pope Clement VI called for an Ecumenical Council in York to reconcile the Lollards back to the Church, which lasted from 1380-1383. The result of the Council created the Celtic Catholic Church, which appeased the Protestant-leaning rulers of the Celtic Union, but was not palatable to John Wycliffe. Wycliffe was condemned to house arrest, and died a year after the council ended. Wycliffe's students subsequently formalized his theological opinions into a list of theses, known as the "Twelve Conclusions of the Lollards". In essence, the Conclusions stated that Church relics and iconography were idolatry, and the prayers for the dead are heretical as purgatory does not exist. It further called for Christians to abstain from military violence and to live simple lives.

The Kingdom of Iceland adopted Lollardy as its official religion in 1388, and attempted to encourage the rest of the Celtic Union to adopt the same. This quickly ended with Ari Aranson's deposition in 1390, and subsequent establishment of the Celtic Catholic Church in Mann. Lollardy continued to be persecuted in the British Isles, until the Inquisition of the 1450s had completely stamped it out. In 1404, the Papal bull De Haeretici by Sixtus V declared that heretics should be punished by life imprisonment, at most.

Hussites

The Hussites was a major religious movement in Western Europe that was originally based on the teachings of Jan Hus (1372-1441), and continued up until the dawn of the Reformation. This was viewed as the most important predecessor for the Dutch Reformation, but also had an impact on the Gallican Church in France. Hus was a theologian and scholar from the University of Prague, coming from a long intellectual tradition of the Renaissance facilitated by the benevolent rule of the Premyslid dynasty. Beginning in the early 1400s, Hus was influenced by the writings of John Wycliffe to begin his own research in criticism of the Catholic Church. He saw the Barbary Crusade as a violent grab of temporal power, hypocritically justified by the leaders of the Roman Church.

Whether or not Hus himself wanted to split from the Roman Church is not immediately clear, and is highly debated between scholars. He facilitated the moderate Hussites to reconcile with the Church at the Ecumenical Council of Rome, and condemned the violence of the Taborites in the Hussite wars. But at the same time, he continued to write criticism of the papacy in his latter years, with his last work comparing the Pope with the Biblical Antichrist. It is pointed out by some historians that the concept of establishing a new religion, as opposed to reforming the existing church, was very far from people's minds even during the early years of the Jungist Reformation.

At the time that Pope Benedict XI called the Ecumenical Council of Prague in 1411, Western Europe was locked in a brutal and drawn-out war over the succession of France. England and Spain supported the Valois claim held by the Duchy of Burgundy, while Lothringia and the Celtic Union supported the incumbent House of Capet. The election of Benedict XI allowed this conflict to bleed into a religious one, as Emperor Vincent believed the Pope (of Spanish origin) to be favorable to the Anglo-Spanish alliance. Furthermore, Vincent's preferred candidate (Cardinal Werner von Falkenstein) almost won the conclave of 1410, except by a single vote.

Emperor Vincent claimed Benedict XI was illegitimately elected, and Falkenstein was the actual Pope. The Cardinal at first was reluctant, but after pressure from the Franco-Dutch alliance he accepted the position as Antipope Mark II. Benedict XI responded by depriving Vincent of his crown, declaring him to be excommunicated and supported Boleslaw V of Bohemia as the new Emperor. At the conclusion of the Imperial crisis, Vincent abdicated as Emperor to the Premyslids, and subsequently saw his kingdom of Lothringia fall apart into Civil War. This chaos in Lothringia would continue until Vincent's full retirement in 1423, and the ascension of King Godfrey I.

The Marcian schism was directly responsible for the proliferation of Hussites into Western Europe. Antipope Mark II declared the Council of Prague was invalid, and reached out to ally with the more radical Taborites. Emperor Vincent may have felt that an Anti-Papal movement could be a tool to wrest power away from Rome. As the central government of Lothringia was no longer able to maintain order, the Hussites were able to embed themselves in the nation as a largely-autonomous community, including many immigrants from Bohemia expelled by the Premyslids. This also became the case in other nations that supported the Marcian schism, mostly in France and Burgundy. One incident is fondly remembered as the "Defenestration of Mons", where representatives of Vincent were thrown out of a window by the Taborites.

The new Pope Martin V opted to not depose the Bishops appointed by Falkenstein, but instead freely pardoned any Bishops that reconciled to Rome. The result of this confounded efforts by the Church to root out the Protestants in Lothringia, as many clerics appointed during the schism were sympathetic to the movement. When Hus died in 1441, he left a commentary on the Apocalypse that predicted the Church will fall into future corruption, and compared the Pope to the Antichrist. The Catholic theologian Domenico Colasanti posthumously refuted this in his own work, "Church and the Apocalypse".

The Hussite Crusade continued throughout the 1420s, although it was never officially called a Crusade. The Premyslid emperor called for a coalition of Catholic military to intervene in the Lothringian Civil War, and fight back against the Taborites. Jan Franz stood out as the most successful military leader on behalf of the Hussites, who improvised "wagenburg tactics" to score significant victories against the Crusaders. This social upheaval in Lothringia and France prompted both kingdoms to adopt an era of religious tolerance, and focus on the plurality of faiths in their respective realms. King Godfrey I declared this in 1450, and King William I issued the Edict of Reims in 1453.

This is what largely prompted Pope Pius II to introduce the Roman Inquisition in the 1450s. The "Roman Bible" published in 1451 was not so much a new translation as it was a biblical commentary, being apologetic towards major Catholic doctrines and suppressive towards Protestants. In 1466, Pope Leo XI created the "Leonine index" of heretical books, highlighting which ones ought to be destroyed. Emperor Sigismund II was the first to eagerly introduce the Inquisition, and for this reason the Pope rewarded him with the title Imperator Christianissimus (Most Christian Emperor) and Defensor Ecclesiae (Defender of the Church). Richard II of England introduced the Inquisition to the British Isles in 1463. Under severe pressure from the Pope, King Henry II finally revoked the Edict of Reims in 1468, but sympathy for Protestantism remained in France up until the establishment of the Gallican Church.

Adamites

The Adamites were a religious movement that, like other Protestant movements, believed in a literal interpretation of scripture is superior to traditional Catholic dogma. To that end, the Adamites believed that the Christian Church ought to be a primitivist society, dispensing with all forms of personal property or central government. They get their name after the Biblical Patriarch Adam, who (according to the Book of Genesis) lived in a primitivist utopia in the Garden of Eden. As such, the Adamites did not wear clothes and went in public naked.

The original Adamites were an Ante-Nicaean sect of early Christianity, during the Roman Empire. The Neo-Adamites first appeared during the Lothringian Civil War of the 1420s, as an extreme branch off of the heretical Taborites. With the failing central government of Brussels, the Neo-Adamites were able to establish their own autonomous community based on political anarchy. This was considered extreme even for the Taborites, and the military leader Jan Franz worked to put down the Adamite movement.

The Neo-Adamites largely disappear from history after this point, as they mostly went underground and lived in secretive communities. They re-emerged in the 1490s as a religious movement in Thuringia, nominally supported by the Thin White Duke. The Archbishop of Mainz called for a Holy War to exterminate the Adamites, which was supported by the Premyslids of Bohemia and the Holy Roman Emperor Henry IX. The Adamites largely disappeared from history at the end of this conflict, but they eventually had an influence on the early Reformation a decade later, and indirectly on the Rätian Union.

Protestantism

Protestantism refers to any from of Christianity derived from the 16th century of Reformation, first begun by Konrad Jung. Protestantism began as a movement against the perceived errors of the Catholic Church, and Protestants reject the Roman Catholic doctrine of papal supremacy. Additionally, various sects disagree among themselves regarding the number of sacraments, the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist, church organization, and the matters of apostolic succession. Protestantism emphasizes the priesthood of all believers; justification by faith (sola fide) rather than by good works; the teaching that salvation comes by divine grace or "unmerited favor" only, not as something merited (sola gratia); and either affirm the Bible as being the sole highest authority (sola scriptura, "scripture alone") or primary authority (prima scriptura, "scripture first") for Christian doctrine, rather than being on parity with sacred tradition. These five solae are considered the basic theological differences that differentiate Protestantism from the Catholic Church.

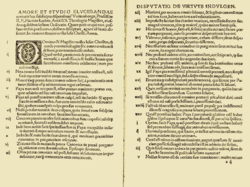

Protestantism originated in Thuringia in 1504, when Konrad Jung published his Hundred-five Theses as a reaction to his perceived abuses of the Catholic Church, most notably the selling of indulgences in the aftermath of the Henrician Civil War. However, Protestantism became divided into a number of distinct sects influenced by alternate theologians, especially after Jung's untimely death in 1507. The name “protestant” derives from the 1510 Diet of Munich led by Ottokar, Holy Roman Emperor, which prohibited the teachings of Konrad Jung; those who followed Jungist teachings issued a protestation against this edict. By the sixteenth century these Protestant sects spread from Germany into Denmark, Norway, Sweden, France, the Lowlands, and beyond. Today Protestantism constitutes the second-largest form of Christianity (after Catholicism), with an estimated total of 800 million to 1 billion adherents worldwide.

Jungism

Jungism refers to a major branch of Protestantism, identifying with the theology of Konrad Jung. Jungism is traditionally dated as beginning with the 1504 publishing of the Hundred-five Theses by Jung, and was later expanded upon by himself and his contemporaries, most notably Johann Freud and Martin Breuer. Jungism first began as an attempt to reform the Catholic Church, but after the excommunication of its leaders and the Catholic Church’s rejection of Jung’s theses, Jungism instead developed into an independent sect of Christianity.

Jungists answers two of the original questions of the Protestant Reformation as begun by Jung: the proper source of authority in the church, often called the formal principle of the Reformation, and the doctrine of justification, often called the material principle of Jungist theology. Jungism advocates a doctrine of justification "by Grace alone through faith alone on the basis of Scripture alone", the doctrine that scripture is the final authority on all matters of faith. This is in contrast to the belief of the Roman Catholic Church, which advocates that authority comes from both the Scriptures and Tradition. Unlike Kafkanism, Jungists retain many of the liturgical practices and sacramental teachings of the Western Church from before the Reformation, with a particular emphasis on the Eucharist. Additionally Jungists differ from subsequent Reformed sects on the nature of Christology, divine grace, the purpose of God's Law, the concept of the perseverance of saints, and predestination.

Jungist sects and churches include:

- Jungist Federation

- Church of Denmark - Founded 1521 by Olaf IV based on the teachings of Michael Kierkegaard

- Church of Norway - Founded in communion with the Church of Denmark

- Church of Sweden - Founded 1515 by Ivar II

Reformed

The Reformed tradition, also known as Reformed Protestantism or Kafkanism is a movement which broke off from the Catholic Church following the development of Jungism. Spearheaded by such reformers as Kurt Kafka, Richard Wagner, and Aloysius Wilde, Kafkanism differs from Jungists on the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist, theories of worship, and the use of God’s law for believers, among other differences.

Kafkanists broke from the Catholic Church in the early sixteenth-century, and differed immediately from the Jungist movement begun in central Germany in 1504. This became most obvious after the Leipzig Debate, in which Jungist representative Johann Freud clashed with Wagnerists from Belgica and were unable to come to a consensus. The namesake of the movement, Austrian reformer Kurt Kafka, is not considered to have been the first of the Reformed movement, as he did not renounce Roman Catholicism and embrace Protestant views until around the 1520s, but his movement quickly became the most widespread in opposition to both the Catholic Church and various Jungist sects. The name Kafkanism was subsequently popularized by Jungists writing in opposition to it.

Reformed sects and churches include:

- Continental Reformed Churches - Kafkanist churches that have their origin in the European continent, used to distinguish them from Presbyterian, Congregational, or other Kafkanist churches, which can trace their origins to the British isles or elsewhere in the world. These churches trace their teachings to the original works of Kurt Kafka, created around 1524.

- Belgian Reformed Church - Founded 1532 in the Kingdom of Lotharingia

- Wagnerism - Major branch of Kafkanism founded 1513 in Luxembourg by Richard Wagner. Wagnerists take scripture as the inspired word of God, placing its authority above any human source, although they also recognize the human element within the Bible. They also maintain infant baptism, uphold a symbolic view of the Eucharist, and believe the church and the state are placed under the sovereign rule of God.

- Presbyterianism - Refers to a Kafkanist tradition based on the teachings of Irish reformer Aloysius Wilde first published around 1534. Presbyterian churches are named for their presbyterian form of church government by representative assemblies of elders. Typical Presbyterian theology emphasizes the sovereignty of God, authority of the scriptures, and the necessity of grace through faith in Christ.

Gallicanism

Gallicanism is a Protestant tradition that developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of France following the French Reformation. The Gallican Church derives its name from the medieval movement advocating for popular civil authority over the Catholic Church, exemplified by centuries of feuds between the Pope, representing the Church, and the Kings of France, representing the state. During the reign of William II, the authority of the Pope was downplayed in a rejection of ultramontanism, although initially remaining in full communion otherwise with the Catholic Church in Rome. Toward the end of his life, and further developed during the reign of his successors Joan the Pelican and Charles IV, Gallicanism developed into an independent church, often considered a via media between Roman Catholicism and Protestantism.

Anabaptism

The Anabaptists trace their origins to the Radical Reformation which occurred following the assassination of Konrad Jung in 1507. The Anabaptist label includes various, differing sects, although each sect generally agrees that baptism should be administered only to those who have consciously repented and requested it for themselves, thus they renounce infant baptism. Anabaptists were also influential in the Great Peasants’ war, and the introduction of the Rätian Union.

Anabaptist sects and churches include:

- Mainstream Anabaptism - An informal term originating around the 1520s, later standardized in 1530 by Benedikt Nietzche and Karl Schopenhauer in the Synod of Jena.

- Starckism - Anabaptist sect founded by Arnold Starck around the year 1522 in the Hanseatic League.

- Dutch Brethren - A radical evangelical group that broke from Wagnerism around 1525 in the Lowlands, believing that Wagner was not reforming fast enough. Rejected infant baptism on the grounds of a sola scriptura argument, as it was not mentioned in the Bible.

- Eastern Jungist Church - Also known as the “Church of Finland”, was an Anabaptist sect that originated from the teachings of Peter Meise II and Saxon missionaries to Russian Finland around the 1520s.

Islam

Islam is an Abrahamic, monotheistic religion that follows the beliefs and teachings prescribed by the Quran, a book of visions and edicts transmitted by the Prophet Muhammad (570-632 AD). Its name derives from the Arabic root s-l-m (or Salaam), meaning peace or perfection, but often translated as "submission" (referencing submission to God). Islam is the second largest religion in the world, embraced by over one billion adherents worldwide. Dozens of nations have Islam as either the majority or official religion, largely concentrated across the Middle East, North Africa, Brazil, and South and Southeast Asia.

Along with the Quran, Islam bases its beliefs on a body of sacred tradition called the Hadith, which was transmitted orally from the companions of Muhammad before being written down in the 8th-11th centuries AD. From these texts, the basic doctrines and requirements of Islam are typically summarized as the "Five Pillars": belief in strict monotheism (shahada), prayer five times a day (sallat), pilgrimage to Mecca, the birthplace of Muhammad (hajj), donating 2% of income to the poor (zakat), and fasting during the month of Ramadan (sawm). It is believed that following these five pillars is sufficient to receive salvation. Islam believes in a single, transcendent God (often designated by the Arabic name Allah), totally disconnected from the created order. The Quran, as the literal word of God, is the only manifestation of God on Earth.

Like Christianity, Islam has divided into multiple sects over the centuries, based mainly on different doctrines and disputes over the succession of Muhammad. However, unlike Christianity Islam has no specific organizational structure. Each community of Muslims gathers to worship on Fridays at a local Mosque, with worship services led by an Imam (or religious teacher). While various clerical offices in Islam require a degree of respect (such as a Kazir or Ayatollah), these do not correspond to any administrative responsibility.

Each Islamic nation has a code of law interpreted from Islamic religious texts, known as Sharia. Sharia law differs between Islamic sects, as well as different schools of theology within each sect. The most liberal branch of Sharia law (Al-Kolombi) is practiced in the Malian colonies of Brazil, while the most conservative Sharia law (Al-Hanbali) is used in the Abbasid Caliphate.

Sunni

Sunni Islam (or Sunniism) is the largest and most mainstream branch of Islam, comprising the vast majority of Muslims worldwide. Its name derives from an Arabic word that means "tradition". Sunni Islam recognizes the traditional succession of Muhammad through Abu Bakr (573-634 AD), the Prophet's son-in-law, who Muhammad designated shortly before his death. The successor of the Prophet is considered to be the legitimate head of the Islamic faith, designated by the title Caliph (or "successor" in Arabic).

The first four Caliphs of Sunni Islam, called the Rashidun (or "wisely-guided") Caliphate, had a non-dynastic succession chosen by a mix of elections and acclamation. From 656-661 AD, a civil war divided the religion between Sunni and Shia, known as the First Fitna. After the end of the war, the Caliphate was reunited under a hereditary dynasty originating from the Umayya clan, known as the Umayyad Caliphate (661-750 AD). The Umayyads brought the Caliphate, as a single nation, to its greatest extent, spanning from Spain to the Indus River. The Umayyads were known for corruption and tyrannical rule, however, and after numerous uprisings the dynasty was deposed in favor of the Abbasid Caliphate, who have ruled ever since.

The early years of the Abbasid Caliphate was known as the "Islamic Golden Age", a time of accelerated scientific and cultural advancement. Even after the Abbasid Caliphate disintegrated as a political entity in the 10th century AD, the Islamic Golden Age largely continued up until the Mongol conquest of the 13th century. It was during this same Golden Age that the Hadiths which are traditionally accepted by Sunni Islam were first compiled and codified. After a period of chaos and numerous conflicts from the 13th-15th centuries, the revived Abbasid Caliphate transitioned from the earlier Golden Age into the Renaissance.

While the traditional seat of the Caliph has shifted numerous times in history, the legitimacy of the Caliphate is inexplicably tied to the ruling dynasty, passed by patriarchal succession within the House of Abbas. The title of Caliph, being the supreme religious head of Sunni Islam, is often described as the "Pope" of its religion. In that capacity, the Caliph does have authority to settle theological disputes, and his theological edicts holds as much weight as if the Prophet himself had said it.

However, there are also a number of differences. The Caliph has no control over the ecclesiastical organization of Islam, as no such hierarchal structure exists. Rather, the Caliph traditionally holds vassalage over all Sunni states, as if they were all components of the same empire. This system was inherited from the early years of the Caliphate, and its relevance has shifted radically over the centuries. After the Caliph, Islamic theology is administrated by the Council of Senior Scholars, also known as the Ulema. The Ulema has existed as long as the Caliphate has, but fell apart in the 13th century with the sack of Baghdad by the Mongols. The Ulema was first restored in Tunisia during the Hafsid Caliphate, which shifted to Egypt when the Abbasid dynasty was restored.

Taymiyyah

Taymiyyah is a fundamentalist theological school of Sunni Islam based on the teachings of Ibn Taymiyyah (1263-1328). It originated in Syria during the early Mamluk Sultanate, and over time spread in popularity over most of the Middle East. Taymiyyah was adopted as the main theology of the Abbasid Caliphate during their rule in Baghdad, and rose to its apex around 1350. It quickly declined after that point, until the Caliph Al-Mutawakkil violently suppressed the school in the 1380s. Taymiyyah's domination of the Caliphate in the 14th century is largely viewed as a reactionary, transitional era between the Pre-Mongol Islamic Golden Age and the Post-Mongol Arab Renaissance.

Taymiyyah derives its theology from a strict, literal interpretation of the Quran, and accepts attributes of God as they are directly described in the Quran. They strongly rejected the Neoplatonic and rationalist theology that was introduced in the Islamic Golden Age, believing that to be a heretical innovation to religion. All creation in Heaven and Earth is merely a reflection of God's will, and consequently only God's will revealed in the Quran is a true reality. Any other attempt at rationalization will fall short of the Quran. At the same time, Taymiyyah scholars were also known for an avid devotion to astrology and numerology, viewing these parts of nature to be the purest aspects of the created order. This accidentally led to the first theory of tides to be developed, in which scholars theorized that ocean currents are caused by forces in the heavens.

Ibn Taymiyyah believed that religion and state should be inexplicably tied together. It is the duty of the secular government to protect the faith of the people, by promoting virtues and punishing vices, in order to create a unified, purified society conducive for the worship of God. Man's only purpose on Earth is to serve God, and only princes who properly serve God have the right to rule. As a result, Islamic nations in the Taymiyyah period would strictly enforce the laws of Sharia, even to the point of capital punishment for the most minor crimes. Ibn Taymiyyah's vision of a pure caliphate emphasized the first three generations after Muhammad, known properly as the salaf.

Taymiyyah was utterly intolerant of both non-Muslims and Muslims of other sects. Even referencing or citing works of Christian or pagan philosophy was considered an act of blasphemy. The persecution of the Coptic Church became so bad that the Pope had to temporarily relocate to Ethiopia. While persecutions of non-Muslims was known sporadically in the past, the Taymiyyahs were considered most unusual by issuing Fatwas against other Muslims who were perceived to be impure. This first targeted extreme Shia sects such as the Alawites and Druze, but later expanded against moderate Sunni schools. Pilgrimage to tombs of Islamic Prophets, as well as works of art in their name was considered blasphemy, and many of these works were systematically destroyed. By the late years of the Taymiyyah period, there were even persecutions against other Taymiyyah scholars who had fallen out of public favor.

Ibn Taymiyyah lived in a time when the Islamic world faced significant pressure from multiple directions. The Nestorian Ilkhanate allied with the Kingdom of Cyprus to attack Egypt in 1298, known historically as the "Nestorian Crusade". Ibn Taymiyyah was known for his harsh criticism of the religious plurality living in Syria and Egypt (including Christians and Shia Muslims), and he considered this state impurity to be the reason for Islam's numerous setbacks.

During his lifetime, Ibn Taymiyyah attracted a considerable following but was largely unpopular among the religious elite of Egypt at the time. However, in Iraq was a different story. After the collapse of the Ilkhanate in 1305, the Islamic scholar Andalah Al-Ebrahimi organized a new theocracy centered at the city of Baghdad, known as the Baghdad Imamate. Al-Ebrahimi was an avid disciple of Ibn Taymiyyah, and gradually worked to popularize his school across Mesopotamia.

After Ibn Taymiyyah's death in 1328, his beliefs rapidly spread across much of the Middle East from Egypt through the Levant and Mosul, in a period known as the "Taymiyyah Revolution". Caliph Al-Mustakfi, who had recently taken control of Baghdad from Al-Ebrahimi, officially adopted the Taymiyyah school in 1330, declaring the current allied states of Egypt, Baghdad and Mosul as components of the newly-organized Caliphate. This rapid development clashed against the remnant Ilkhanate ruling from Tabrzi, which still had de jure claim on the Middle East. After a conflict from 1332-1335, known as the Ilkhanate Civil War, the Taymiyyah states officially secured their hegemony across the Middle East, pushing the Turko-Mongols back to Iran.

After a brief period of peace, the Taymiyyah sect began to turn on itself. The new Caliph Al-Wathiq I sought to annex the Mamluk Sultanate directly, and invaded Syria in 1341. The long and brutal Taymiyyah Civil War lasted until 1349, allowing the Caliphate to annex all of Syria, Levant, and Cilica, as well as sack the city of Alexandria. The Taymiyyah sect gradually fell out of favor after the death of Caliph Al-Hakim in 1352. Exhausted from conflicts, and demoralized by the Black Death, the Arab elites became disillusioned by the Caliphate's inability to create a purified state. In 1386, Caliph Al-Mutawakkil issued a fatwa against the Taymiyyah scholars, and brutally purged them out of Mosul and Baghdad.

The Taymiyyah Revolution had profound effects on the history of Sunni Islam, both within and outside the Middle East. Taymiyyah's brutal suppression of impurity, to the point of civil war, ultimately demoralized the concept of fundamentalisms itself, paving the way for the Arab Renaissance of later centuries. Outside of the Middle East, most Muslim nations reacted negatively to the movement, and to one degree or another distanced themselves from the ruling Caliphate. This was the impetus for the Delhi Sultanate to adopt the Chishtiyya school of Islam, as well as the justification of Ibn Yunus to establish the Yunnism in West Africa. In Iran, the last years of the Ilkhanate adopted Shia Islam to cut relations with the Abbasids, and this Twelver Shia movement quickly spread to Persia's successor-states.

Chishtiyya

Chishtiyya Islam, also known as the Chishti Order, is a liberal school of Sunni theology that is predominate in northern India and Afghanistan. It originated as a Sufi order of Islamic mysticism, but in the 14th century it became the official religion of the Delhi Sultanate. Chishtiyya emphasizes love, tolerance, and respect as the most valuable virtues in Islam.

The Chishti Order believes that perfect faith in God is achieved by abandoning ones worldly possessions and embracing God's benevolence and love. A perfect knowledge of God is also achievable by combination of meditation and recitation, devoid of music or sensuality. Chishtiyya also encourages a separation of religion and state, believing that secular involvement of religion innately lacks a spirit of charity, and therefore will always be corrupt. Like other Sufi orders, the Chishti also practice the ritual Sama dance.

It is believed to have been founded by Abu Ishaq Shami (d. 940 AD), who was one of the earliest Sufi theologians in Afghanistan. After the time of Shami, the Chishtiyya were protected under a local Emirate, before it migrated into India in the 13th century. Moinuddin Chishti (1143-1236) first introduced Chishtiyya to the subcontinent, and after him his disciples split into two different schools. His most significant student was Nizamuddin Auliya (1238-1325), who spread the Order all across India and Bengal. In the 1330s, the Khaji dynasty of the Delhi Sultanate adopted the Chishti Order to embody the state religion, in opposition to the ultra-conservative Taymiyyah school of the Abbasids.

Shia

Shia Islam, also called Shi'ism or Shi'ites, is the second-largest denomination of Islam. It believes that Ali ibn Abi Talib (601-661 AD), the cousin and adopted son of Muhammad, was the legitimate successor of the Prophet. While Sunni Islam adheres to a traditional succession of Caliphs that have often changed dynasties, Shia Muslims only recognize the direct male descendants of Ali as having religious authority. While the title of "Caliph" is recognized in some Shia sects, the main title applied to Ali is Grand Imam or "Viceroy of the Prophet".

The first twelve descendants of Ali continued the title of Grand Imam until Muhammad Al-Mahdi, the last Imam, disappeared in 880 AD. The mainstream sect of Shia Islam, called Jafari or Twelver, believe that Al-Mahdi was hidden (or Occulated) until the end of time. However, over time Shia split into a variety of different sects that recognize different lines of succession, many of which eventually adopted similar doctrines of Occultation when their lineage died out. Shia Islam reached an apex of their power during the Fatimid Caliphate, an Ismaili theocracy that traced their lineage directly from Ali and his wife Fatima.