Second Sino-Japanese War

| Second Sino-Japanese War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Pacific theatre of the Great War | |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Foreign support: |

Foreign support: | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 5,700,000 (peak, c. 1938) | 1,724,000 (peak, c. 1935) | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 1,080,000 military deaths | 556,700 military deaths | ||||||

The Second Sino-Japanese War, also called the China-Japan War and known in China as the War of Resistance against Japanese Aggression (Chinese: 中國抗日戰爭; pinyin: Zhōngguó Kàngrì Zhànzhēng), was a military conflict primarily between the Republic of China and the Empire of Japan fought between 1927 and 1938 in mainland China. From 1932 it was part of the broader global Great War and was the largest Asian war of the 20th century, with over 9.5 million total deaths, the majority being Chinese civilians. It was the largest war on the Asian continent and led to China being one of the countries with the highest number of casualties among all of those involved in the Great War. Sometimes the Second Sino-Japanese War is referred to as being part of the Pacific theater of the Great War, which saw Japan fighting against European and North American powers on Pacific islands, but most historians regard it as a separate conflict.

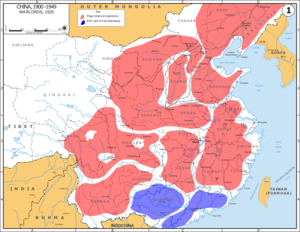

The war began in the spring of 1927 when the Japanese Kwantung Army, occupying parts of Manchuria (then a region of northeastern China), intervened in the Warlord Era power struggle over which warlord clique would control the Chinese central government in Beijing. However the Japanese attempt to place a pro-Japanese faction in control of China by force backfired, with different warlord cliques and political movements in China unifying around fighting the Japanese, at which point Japan sent in reinforcements from the mainland. Negotiations between the Chinese and Japanese governments failed to resolve the conflict and it escalated into total war between the two nations.

The escalation of the war in May and June 1927 saw a Japanese Army offensive capture Beijing and Tianjin from the Chinese National Revolutionary Army relatively quickly, which was followed by the Japanese occupation of most of North China by the end of that summer. Chiang Kai-shek, the president of China and leader of the Chinese army, had moved the capital from Beijing to Nanjing in central China. Japanese forces spent the fall of 1927 positioning themselves for a drive towards the new capital along the north-south railway routes, while negotiations between Chiang's representatives and those of the Japanese cabinet failed to reach a peace agreement between China and Japan. The Chinese forces resisted but continued to be pushed back as the Japanese launched their offensive, with the Japanese taking critical cities and railway junctions on the way towards Nanjing. But the Battle of Xuzhou ended in a Chinese victory after a counterattack threatened to cut off the Japanese supply lines outside the city, making the Japanese lift the siege and withdraw in April 1928. Over the next few years Chinese forces pushed back the Japanese as their control over the occupied territories in north and central China was shallow, retaking Beijing in December 1932 during the Hundred Regiments Offensive. After it was nearly driven out of China completely, Japan mobilized more forces to the Asian mainland and launched Operation Ichi-Go, retaking much of the territory from the Chinese. The fighting was concentrated in central China between the Japanese forces and the Nationalist Chinese regular army and to a lesser extent in North China against Communist guerillas in the mid-1930s.

Background

Since its modernization with the Meiji Restoration of 1868, the Japanese Empire began expanding to secure a sphere of influence in greater East Asia and protect itself from European colonial powers. Japan defeated the declining Qing dynasty of China in 1894–1895 to dominate Korea, Manchuria (northeast China), and the outer island chain (including Taiwan and the Ryukyu Islands), and then defeated Russia in 1904–1905 to solidify its control over Korea and north China, preventing Russia from taking control of it or threatening Japan. These wars left Japan with a dominant position in the Far East, especially in China, which was being divided up into spheres of influence among competing European Great powers that had interests there since the early 19th century – notably Britain, France, Russia, and Germany. Since Japan's own modernization in the 1870s, it was rapidly becoming a major player as well. This was symbolized in the Eight Nation Alliance intervention during the Chinese Boxer Rebellion of 1900, which included Japan, the United Commonwealth, and the aforementioned European countries, along with Italy and Austria-Hungary. Japan came to an agreement with Great Britain in 1902 that clarified and balanced Japanese and Western commercial interests in China. However, the increasingly politicized leadership of the Imperial Japanese Army believed in expanding further in China as it had all of the resources that the Japanese economy needed, and that it was Japan's duty to turn the country into a total Japanese protectorate and ensure Japan's dominance of the Far East for decades to come. This school of thinking came to be extremely influential in the Army leadership and Japanese politics.

The Qing dynasty ended its 150-year long decline with the October–December 1911 Revolution, which ended with the general Yuan Shikai forcing the last Qing emperor to abdicate, leading to the declaration of the Republic of China in January 1912. The Qing dynasty had deliberately kept its military weak to prevent a coup against them, dividing up the Chinese military forces among provinces and not rotating the soldiers or officers among them, leading to the creation of strong regional loyalties among the troops as well as personal ties to individual generals, with officers becoming loyal not to the state or the nation but to the general that promoted them. Yuan Shikai, who became the first President of the Republic in 1912 for his role in arranging the young Emperor's abdication, was able to keep this system together as he had the strongest army in China loyal to him and many of the generals in the provinces had been his former officers under his command, and thus accepted his leadership. Although China held democratic elections in 1912 and 1913, and nominally had a civilian government in Beijing that was recognized by the Western powers and Japan, most of the real power was in the presidency of Yuan Shikai, as he led the strongest army and commanded the loyalty of the generals, who were increasingly becoming quasi-independent regional warlords with their power base being their local province.

In 1913, the Chinese revolutionary leader Sun Yat-sen had become disillusioned by this situation and his Kuomintang (KMT) party tried to launch a "Second Revolution" against Yuan's dictatorship, but it was crushed and the leaders were forced into exile. In late 1915 and early 1916, Yuan tried to make himself Emperor at the head of a new Chinese monarchy, but this was not supported by most of his own generals, or by Western governments, leading to an open rebellion in the southern provinces by multiple warlords. Under immense pressure from the entire nation, Yuan was forced to "abdicate" and resumed his role as president, but he died from health problems a few months later. The war against Yuan's attempt to make himself emperor and his death shortly after marked the start of the Warlord Era in China.

With Yuan's death in June 1916, the system could no longer be held together. Infighting broke out among the generals of the Beiyang (Northern) government in Beijing to determine who would succeed him, while the provinces of the South that had declared independence from Yuan's "empire" were essentially independent of the North, led by their own local warlords, creating a lasting North-South split. Sun Yat-sen returned to China amidst this situation and formed a new KMT-led national government in Guangzhou in 1917, in an ineffective attempt to reunify the country, but it had no real power as they did not have any military forces under their command. While the Beiyang government in the North could no longer exert control over most of the regional warlords outside of North China, it still remained the internationally-recognized government of China on paper – granting it access to foreign loans and assistance. Generally, the office of president was held by the most powerful Beiyang warlord or their puppet, while cabinets and prime ministers were quickly appointed and dismissed by the whims of warlord intrigue.

As China descended into warlordism and civil war, the militaristic Japanese leadership saw an opportunity to increase Japan's own influence over China in the name of defending Japanese and Western business interests from the violence and chaos. With Japanese backing, Marshal Zhang Zuolin, a former bandit gang leader who had become the ruler of Manchuria by 1916, declared independence of the First Manchu Republic in December 1917. Japanese troops secured strategically important parts of Manchuria, including the railways and major cities, to support the region's "independence." Duan Qirui, who had become prime minister and had replaced Yuan as the new head of the Beiyang (Northern) warlords, was preoccupied with a power struggle against other generals of the Zhili Clique and the Anhui Clique, the two major factions in the North. The West did not recognize Manchuria's "independence," but tentatively accepted Japan's "protection" of it as it was part of Japan's role as the protector of foreign business interests in China and thought that Japan could bring good governance to an otherwise lawless region. The Japanese occupation and Manchuria's independence declaration caused outrage among the Chinese public, creating the May Fourth Movement. It marked the beginning of Japan's increasing interference in the internal affairs of China that would lead to outright war between the two countries in 1927.

In the South, Sun Yat-sen's new government won support from the more militarily powerful Guangxi Clique and Yunnan Clique warlords, as well as from many politicians of the former elected parliament in Beijing, but their attempted offensive towards the north was stopped by Duan Qirui's Zhili forces. Internal disagreements and power struggles within the southern movement led to the collapse of the Sun Yat-sen unity government by 1919. Any serious unification efforts took a break as both the northern and southern warlords started fighting among themselves. In the north, the Zhili-Anhui War led to the defeat of Duan in 1920, who resigned in favor of Wu Peifu as the new leader of the Beiyang warlords. In the south, disagreements between the Guangxi, Yunnan, and Guangdong cliques led to the Guangxi-Guangdong War, forcing Sun Yat-sen and his loyalists to abandon the south and evacuate to Shanghai. The fighting in China at this time was observed by officers from Europe and North America, as it saw the largest scale usage of artillery, machine guns, and armies with hundreds of thousands of soldiers since the Russo-Japanese War, almost becoming a testing ground for new technologies and tactics.

Prelude to war

By 1923, the Zhili Clique had secured its control over North China and therefore the Beiyang government. However, President Cao Kun and Premier Wu Peifu were not satisfied with this fiefdom, they wanted to recover the Manchurian territory and the rest of the China as well (with the Great Wall now forming an approximate border between China and the Japanese-backed Manchu Republic). To placate Chinese public opinion – which had become strongly anti-Japanese since Manchuria broke off with Japan's open support in 1918 – and to build up support for their rule, Cao Kun and Wu Peifu also became strongly opposed to Japan's presence in China and Manchuria, and decided to launch a military offensive. With the southern warlord cliques too divided to pose a threat to the Zhili for now, they made the decision to concentrate their army – over 500,000 men – for an attack on Manchuria in 1924. It was expected that Japan would not use its forces to openly attack the Chinese army, as long as they were not directly attacked, because that would enrage the European and Anglo-American powers and could lead to them intervening on China's behalf.

The Japanese Embassy had learned of the Zhili Clique's preparations to restore the Manchurian provinces to China. In October 1924, as troops were being positioned in preparation for an offensive on Manchuria, the Japanese secretly provided assistance to Feng Yuxiang. He was a general of the deposed Duan Qirui's Anhui Clique, a former rival for power to the Zhili in the North. Feng became dissatisfied with the corrupt way the Zhili were running the government, and he sympathized with Sun Yat-sen's movement in the south to reunify the country. In the spring and summer of 1924 Japan supplied him with money and arms in the hopes that he would topple the Cao government. The Japanese wanted to get rid of the Zhili Clique because of its anti-Japan policies and replace it with the more compliant Anhui Clique. Meanwhile, with the strategist Wu Peifu organizing the invasion of Manchuria, the Zhili expected to be victorious there and then follow it up with a campaign to defeat their remaining weakened rivals in central and southern China one by one.

On 23 October 1924, Feng's troops captured key sites in Beijing and placed President Cao under house arrest. The "Beijing Coup" took them by surprise and was successful. At the same time, the Manchu National Army led by Zhang Zuolin launched a surprise attack on the troops amassing near the Great Wall. Achieving full surprise, the Manchu forces routed the unsuspecting Zhili army and forced it to retreat south. They fought the Manchus to a stand still at Tianjin, leading to a ceasefire. Feng Yuxiang was in control of Beijing and Cao was imprisoned, while Wu Peifu and his remaining forces fled to central China to his ally Sun Chuanfang. All of North China was now back under Anhui control, with Feng becoming President of the republic and renaming his forces the National Army (Guominjun). His relations with the Manchus remained turbulent due to the need to respond to Chinese public opposition to Manchuria's independence, but he came to a secret arrangement with the Japanese to restore a competent provisional government in Beijing, with Duan Qirui once again as premier. The provisional government opened negotiations for national reunification with Duan, Sun Yat-sen, Feng, and Wu, but these did not lead anywhere and Sun died in March 1925.

With the powerful Zhili Clique shattered and defeated by 1925, it changed the balance of power in the North, with multiple factions now vying for control, and also bought time for Chiang Kai-shek to build up the KMT's National Revolutionary Army in the south, since the Zhili would have most likely been able to crush the KMT had they been victorious against the Manchus. In the north, Feng Yuxiang controlled most of the army and had real power while Duan Qirui only had a small force around Beijing but was nominally the head of the Beiyang government, and Zhang Zuolin, the leader of Manchuria, had an even stronger army north of the Great Wall and could influence China's nominal government. This created a tenuous balance, which started to break down in 1926 as Duan tried to play off Feng and Zhang against each other to gain more power for himself. The catalyst was a large demonstration against imperialism, warlordism, and Japanese aggression that took place in Beijing in July 1926, with hundreds of thousands of protestors led by young university students, and Feng's Guominjun, at the request of the Japanese and Zhang's Manchurian regime, ended up brutally crushing the protests. It was strategically a terrible decision and led to his downfall.

Feng's suppression of the Chinese mass protest movement meant that the Guominjun lost all popular support, with mass riots breaking out in North China. Feng tried to open negotiations with Chiang Kai-shek in a bid to save his position, but Chiang was in a power struggle for leadership of the KMT at the time with Wang Jingwei, and refused to get involved, seeing it as part of a plot by Wang to get him to leave his power base and allow Wang to take control of the KMT. Meanwhile Wu Peifu and his reorganized Zhili Clique allies in central China began to march on the capital in August-September 1926, defeating some Guominjun units along the way and winning the popular support of the rioting crowds. Zhang and the Japanese, realizing their mistake and that the Anhui Clique government was about to collapse in the face of open rebellion, took action to try to stop the anti-Japanese and anti-Manchu oriented forces from taking the capital. For the rest of 1926 Wu Peifu's forces secured the areas of North China to the south of the Beijing-Tianjin area, cutting off the capital region from the rest of the country, while the remnants of Feng's Guominjun remained in the areas between Beijing and the Great Wall. Morale dropped and the Guominjun began hemorrhaging soldiers as mass defections took place to the approaching Zhili army, with Feng and Duan being seen as Japanese puppets.

Zhang indicated that any movement by the Zhili forces on Beijing against the Guominjun would result in a Manchu intervention, and the Japanese Kwantung Army, the IJA force in Manchuria led by General Baron Nobuyoshi Mutō, also decided to intervene regardless of orders from the civilian government in Tokyo to restrain themselves. Japan's relations with the British and the Anglo-American countries, namely Sierra, were becoming strained because of perceived Japanese meddling and abuses in China. The large Overseas Chinese community in Sierra and Astoria also held large protests in cities like Porciúncula and Seattle to bring attention to Japan's actions in China. The IJA leadership in Manchuria and Korea was becoming increasingly independent of Tokyo, however, and was full of jingoistic nationalists. During this standoff, in November 1926, Wu Peifu and Chiang Kai-shek came to an agreement for the Zhili Clique to enter an alliance with the KMT, and similar overtures were made by Chiang at this point to even the Guominjun and the Anhui Clique remnants led by Feng and Duan, asking them to change sides and live up to their patriotic duty. They agreed to Chiang offering them a way out of their position and on 24 December 1926 the First United Front was created by the forces of the KMT, Zhili, and Anhui Cliques. The Guangxi and Yunnan Cliques in the south also gave this alliance their backing, along with many other more minor warlord factions in other parts of the country, such as the normally neutral Shanxi Clique in the mountainous provinces to the west of Beijing.

The Japanese and Zhang's Manchu Republic overplayed their hand and ended up creating a rising feeling of nationalism among all Chinese, and created a moment of national unity on the political level that had not been seen arguably in decades. After Feng and Duan changed sides and entered an alliance with the KMT and the Zhili, Zhang Zuolin panicked and immediately sent his troops towards Beijing in January 1927. They began fighting Feng's Guominjun, pushing them south towards the capital as Wu Peifu's Zhili army moved north to back them up, followed by Chiang's KMT. The Guominjun (Anhui), the Zhili, and other warlord armies all now – at least nominally – accepted the KMT's leadership and were part of the National Revolutionary Army. In practice, they were still quasi-independent and Chiang and his Whampoa Military Academy-trained officers had to negotiate with the warlords rather than give them orders, something that would weaken their army's ability to respond to changes on the battlefield.

By mid-February, the lines had been drawn up around Beijing, and the Chinese capital was now under (nominal) KMT control for the first time. The KMT now claimed to be the legitimate leadership of all China, further increasing its support among the Chinese people, as most of the warlords nominally pledged their loyalty to the KMT-led Beiyang government. Chiang's and Wu's armies, along with Feng's remaining forces (together as the Chinese National Revolutionary Army), had fortified the ancient capital and fought off an assault by Zhang's Manchu National Army from the 12th to the 28th of February. The MNA was better equipped compared to the NRA force, having more artillery and armored cars, but was outnumbered by the vast armies now gathered in the Beijing-Tianjin area, with the railroads steadily carrying more troops from the south and center of China to the north (the fact that there were almost no railroads and only dirt paths through the mountains connecting the Beijing area to the population center of Manchuria greatly worsened the MNA's logistics).

On March 7, the NRA launched a counterattack, dislodging the MNA from its positions, and the retreat quickly turned into a rout as the Manchu Republic army fled back to the Great Wall. The First Battle of Beiping–Tianjin was a victory and energized the public's support for the United Front movement and the KMT with the defeat of the Manchu army, which was seen as an appendage of the Japanese. At this point, General Muto's Kwantung Army numbered nearly 300,000 troops and decided to enter the conflict to prevent Zhang's Manchuria from being overrun by the Chinese. The IJA began sending divisions south as the MNA tried to stave off Chinese NRA attacks. Finally, the Battle of the Great Wall stopped the NRA's advance as better trained and equipped Japanese divisions entered the fight and dealt the NRA heavy losses, forcing a withdrawal back south towards the capital by May 1927.

Negotiations were underway through the Chinese Embassy in Tokyo, as the Japanese civilian government argued over how to respond to the escalation in China. Chiang let them know through the ambassador that he was actually open to negotiation with the Japanese despite his public statements. But the more moderate Wakatsuki Reijirō government fell in April 1927 after it lost the Army's support, and he was replaced by the more aggressive Tanaka Giichi as Prime Minister of Japan. Tanaka initially thought the Kwantung Army leaders were way out of line, but he more strongly supported the idea of dividing China into spheres of influence, seeing the rising KMT-led national unity government of Chiang Kai-shek as a threat. With the 1926 Russia–Japan Agreement securing Japan's northern flank by Russia confirming Japan's leading role in the Far East and in China especially, it freed up one of the main concerns some Army officers had about attacking China without first having a treaty with Russia. In a sense, the creation of the Triple Alliance, which included Russia and Japan along with Germany, led to Japan's war with China. Tanaka approved sending more Army troops to "defend Manchurian sovereignty" and to "restore order" in North China, with the aim of installing a pro-Japanese government there. His cabinet came up with a list of demands for peace with China, which included a recognition of Manchuria by China, a withdrawal of NRA forces from the Beijing-Tianjin corridor, and the setting up of Japanese garrisons in Mongolia and the Beijing area as a protection force, as well as Japanese advisors to be placed in the Chinese army and every government ministry. The Chinese ambassador informed them of Chiang Kai-shek's rejection of most of those demands, and Chiang's list of counter-proposals were rejected by the Japanese cabinet. Further negotiations were fruitless and on April 25 the Chinese ambassador and his embassy staff left Japan by ship to Shanghai.

Japan and China were now at war because of the actions of the Kwantung Army commanders and the Manchurian government of Zhang Zuolin, backed by the Imperial Army's influence on the Tokyo government. Large reinforcements from the home islands began arriving on the mainland to assist the Kwantung Army, which was now preparing to push the NRA out of North China and to capture Beijing. In Manchuria, the occupying Kwantung Army took control of the "inept and corrupt" Zhang government, ending the Manchu Republic and replacing it with the Empire of Manchukuo, putting the last Qing emperor Puyi nominally in charge of it while filling many posts with Japanese advisors. If before the West could ignore Japan's limited presence in Manchuria and see that republic as being at least somewhat legitimate, now it was clear that Manchukuo was a thinly veiled Japanese puppet state. Only Germany, Russia, and Japan's other allies recognized it. But Britain, France, and the Anglo-American powers still did not openly get involved in the war, instead providing arms for the Chinese army and diplomatic pressure on Japan. The Japan-China War was now the center of global attention as it became the largest and deadliest conflict going on in the world, surpassing the Mexican Revolution and the Spanish Civil War, in terms of the number of soldiers (with the First Battle of Beiping-Tianjin alone involving over one million men) and the usage of recently invented weapons and technologies.

Course of the war

The Fall of North China

The first actions of the war would occur in North China. On May 1, 1927, it became known that Japan's Imperial General Headquarters authorized the deployment of five divisions – one from Korea, one from the Kwantung Army in Manchuria, and three from the home islands – into North China. On May 5, a new directive divided the Japanese forces in the region, with the forces in Manchuria remaining part of the Kwantung Army while the newly arriving forces became the Northern China Area Army, with General Kenkichi Ueda in command. The lack of infrastructure and the mountainous terrain south of the Great Wall slowed down the advance of the Japanese, which had arrived at the ports of southern Manchuria. Nonetheless, they defeated several scattered Chinese battalions in the area and reached the Beijing area by late May. Japanese forces completed their deployment outside of the Chinese capital and launched their attack in early June. The Japanese, being better equipped and organized, gave the National Revolutionary Army (poorly organized combined warlord forces) significant losses, although a successful counterattack briefly retook the town of Langfang to the north of the capital before the NRA was forced withdraw. Tianjin, the sea gateway to Beijing on the coast, was also taken around that time after intense fighting, with the assistance of the Imperial Japanese Navy.

On June 10, Chiang decided to preserve his army and gave orders for the remaining troops in the Beijing-Tianjin area to retreat south along the lines of the Tientsin-Pukow Railway and the Peiping-Hankow Railway. The retreat from Beijing-Tianjin left the rest of North China undefended, leading to its occupation by Japanese forces by the end of August. Lieutenant General Takashi Hishikari entered the city of Beijing on June 23 and held a military parade. The swift Japanese victory over the Chinese forces in North China was expected by Chiang, who had weeks earlier issued a decree moving the capital from Beijing to Nanjing, where the KMT's civilian organs were already mostly located. The National Revolutionary Army's losses were considerable, but the combined forces, with Wu Peifu, Feng Yuxiang, and Duan Qirui in command, managed to withdraw towards the Shandong and Henan provinces with much of their forces intact. Even the loss of the capital didn't stem the high morale and energy of the Chinese to fight the Japanese invasion. The Japanese Imperial General Headquarters was encouraged by their success in taking China's capital, which was also a major railway junction as well as the political center of the country, but Emperor Hirohito believed it would take several months to fully consolidate their control over the region, overriding the desire of the Northern China Area Army and the Kwantung Army leadership that wanted to launch immediate offensives into Henan, Shandong and Shanxi to pursue the retreating NRA.

From late July to early August 1927, as the Japanese occupied the rest of North China and the NRA forces re-positioned themselves to the south and west of the region, Chiang took advantage of the break in the fighting to convene the National Assembly in Nanjing, an ad-hoc body under the Constitution that could be called to make important decisions. The central government, headed by parliamentary speaker Lin Sen and by Wang Jingwei, decided to reorganize the structure of the government and military in response to recent events, and to integrate the warlord forces further under government control. Chiang was confirmed as President of the Republic of China as well as Chairman of the Military Commission (which replaced the Ministry of War) and was granted emergency powers. For military purposes the country was divided into four War Areas, with each having the authority over all of the troops in its region (at least theoretically). Wu Peifu was named as commander of the Central War Area (which included the Yangtze River Delta, Shanghai, and the new capital Nanjing). Yan Xishan, military governor of Shanxi, led the Northern War Area (North China); Li Zongren, head of the Guangxi Clique, led the Southern War Area (South China); Yang Zengxin, military governor of Xinjiang, led the Western War Area (Xinjiang, Gansu, and Qinghai). Duan Qirui became the Chief of the General Staff, Feng Yuxiang became the vice commander of the Northern War Area. Many of Chiang's Whampoa-trained officers, who were more professional and personally loyal to Chiang and the Nationalist Party, filled the mid-level positions below the warlord commanders, and many became division or field army commanders subordinated to the War Area Commands. This new structure was accepted by the warlords for the most part, and also had the practical effect of increasing Chiang's authority over the warlords as well as more direct command over their troops.

The Japanese high command also tried to take advantage of the fragmented state of China to reach out to individual warlords, asking them to change sides in exchange for short-term benefits as well as posts in a future Japanese-backed Chinese government after the defeat of Chiang's coalition. But, although the warlords still had some disagreements and conflicts among themselves, the result was mostly negative. They underestimated the degree of unity that had been reached in opposition to Japan and Manchukuo within China. But ironically, this also limited Chiang's ability to negotiate, even if the Japanese side was capable of coming to a reasonable agreement. As skirmishes along the front line resumed in the fall of 1927 and the Japanese Army positioned itself for its drive south into central China, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Jingwei quietly led a delegation to neutral Portuguese Macau at Chiang's secret request, where he met with representatives of the Japanese General Staff. The Japanese side was led by the retired general Iwane Matsui, who spoke fluent Chinese and had always had an interest in Chinese civilization, and sympathized with Chiang Kai-shek's Nationalist movement. The Japanese government did not fully empower him to make final decisions, and neither Prime Minister Tanaka nor the IJA General Staff Office were fully committed to the talks, as they did not think Chiang would be able to reach an agreement with them, but they did hope for an end to the war if the Japanese Army could eventually reach Nanjing.

Matsui hoped for peace and an alliance between China and Japan, and was the leading voice in the "pro-China" faction in the Japanese government, assuring Wang that the Japanese leadership was to be lenient on its peace terms. Several issues were discussed at the Wang-Matsui talks. Chiang had actually agreed to recognize Manchuria's independence, but asked that China be given time for this to happen due to Chinese public opinion being so opposed to it, and settle for a secret agreement between Japan and China in the meantime for China's tacit de facto acceptance of Manchurian independence. Matsui thought this would be acceptable, and the main points of contention were regarding Japan's influence and control in China proper. Chiang even accepted the possibility of Japanese Army units being stationed within China itself and providing training to the Chinese Army. However, he did not want Japanese advisors to have any command authority, and certainly no Japanese advisors in government posts giving orders to Chinese officials. He also wanted significant financial investments from Japan to build up China's economy and modernize it, not just for the resource extraction industry for the benefit of Japan. The two sides agreed on letting Japan exploit the resources in North China and receive most favored trade nation status, in exchange for investing money in all of China as well, particularly in infrastructure, and for a joint Sino-Japanese defense force in some parts of China, and Japanese training of Chinese troops. Also there would be a recognition of Chinese sovereignty by Japan. But they could not agree over the extent to which Japanese advisors would have influence over the Chinese army and government.

Both the Chinese and Japanese delegations left Macau in late September with optimism and hope after the talks. This was even more true when on October 8, 1927, Prime Minister Tanaka gave a radio speech where he spoke about a "New Order in East Asia," consisting of pan-Asianism, anti-Landonism, unity against Western imperialism, and "the Empire extending a helping hand to the hundreds of millions of people across Asia, including in China and India." But ultimately, Tanaka and most of the military bureaucracy found the terms too lenient, and the more hard-line faction disagreed with the terms. The "Imperial Way faction" believed that Chiang would either be forced to accept all of what they wanted or he would be overthrown in palace coup by warlords after his army was defeated on the battlefield. By late October, Tanaka and his cabinet decided to reject the outcome of the Macau talks and adopted a wait-and-see policy as the war progressed.

Battles of Central Henan, Shandong, and Jiangsu

In early November, the Japanese Northern China Area Army launched a general offensive from the Kalgan–Beijing–Tianjin area along major railways southwards, capturing lightly defended Baoding and Datong by the middle of the month. The IJA 12th Army was tasked with securing the southwest, proceeding from Datong towards Taiyuan into Shanxi province, but facing more resistance and logistical problems because of the lack of railways to the west. The IJA 1st Army, on the main focus of the campaign, captured Baoding and then proceeded along the railroad towards Jinan, a major transportation and urban center in Shandong province, beginning a siege of that city on November 28. Taking the critical railway junction at Jinan, which connected North China to the Yangtze River Delta, ultimately to Nanjing and Shanghai, was an important step of the campaign. The IJA first secured the area south of the city, including the railway, cutting it off from the outside. The NRA forces in the area, numbering about 150,000 and led by Feng Yuxiang, fought in the heavily fortified outskirts and then the urban districts. The advance was slow in brutal house-to-house fighting, some of the deadliest fighting experienced by the Japanese Army in the war so far. Two more brigades were sent to assist the 1st Army in December, and in early January 1928 the outer defenses of the city were finally breached, as the Northern China Area Army had exhausted its remaining reserves. From there it was surrounding and eliminating individual Chinese units in the city. Feng ordered a retreat of all remaining NRA forces from Jinan on January 14.

Taiyuan held out longer as the bulk of the Northern China Area Army had been sent to Jinan, and the terrain and poor infrastructure in Shanxi made the transportation of Japanese units more difficult. Yan Xishan's forces succeeded in fighting off Japanese attacks throughout December and January, along with Nationalist partisans sabotaging the railways, leading to General Ueda to temporarily halting the operation in the direction of Shanxi and focusing on Jinan until more reinforcements arrived from the home islands and Manchuria. Meanwhile, about 1.1 million NRA troops had been redeployed, with Feng Yuxiang's new First War Area covering the Xuzhou direction of the railway from Jinan, while Wu Peifu's Central War Area defended the Anyang-Zhengzhou direction. By this late February, additional IJA divisions had arrived in North China. About 250,000 Japanese troops advanced towards Xuzhou, aiming to capture it as it was the last major railway junction on the way towards Nanjing. The fighting there began on March 4, and Chiang sent additional units from all over south and central China to prevent a Japanese break through. Li Zongren's Guangxi troops and Muslim divisions from the far west of China were deployed.

The Battle of Xuzhou was even more intense than the Battle of Jinan, with especially the Muslim troops led by the general Ma Biao being noted by the Japanese for their fanatical resistance and bravery in battle. Nonetheless areas around the city had been encircled by the Japanese by the end of the month, and an attempt to break through to the city by Chinese divisions from the south failed. The encircled defenders continued to fight, holding up the IJA at Xuzhou. The Japanese had sustained over 100,000 casualties in the Xuzhou battle at this point. In the middle of the month, an army of Chiang Kai-shek's personal elite divisions at Nanjing, which had been trained by British and French officers and were much better equipped than a normal NRA division, had moved along the coast of Jiangsu province and launched a counterattack on the Japanese-controlled railway connecting Xuzhou to Jinan. The rear area was less defended due to most of the forces being at the city, and soon the Japanese had to call in reinforcements to prevent their line from being breached and the IJA 1st Army from being cut off entirely in the Xuzhou pocket. The attack by Chiang's own elite divisions had briefly panicked the Japanese command, and although Chiang ordered them to end the operation and withdraw, it caused enough damage that the Japanese still ordered a temporary withdrawal from Xuzhou to reorganize their formation.

By the start of April 1928, almost exactly one year since the war began, the Japanese First Army completed its withdrawal from the Xuzhou area back to Jinan and the Shandong province. General Kenkichi Ueda decided to wait until more reinforcements arrived and they would be able to strengthen their position instead of overextending themselves. The break in the fighting led to certain elements in both the Japanese and the Chinese governments to again try to make contact and negotiate. At this time, Chiang Kai-shek also began speaking with the ambassadors of Great Britain, France, and Sierra (as the foreign embassies were evacuated to Nanjing from Beijing), hoping to receive more support in terms of weapons and supplies as China's industries were devastated by many years of civil war and mismanagement.

Negotiations and stalemate

Although Chiang Kai-shek authorized his Foreign Minister, Wang Jingwei, to continue his talks with their Japanese contacts, he did not expect any progress and began more serious discussions with Sierran and British officials. The Japanese invasion of China had caused outrage and sympathy for the Chinese among much of the Western public and media but until then the governments of those countries had been reluctant to commit any kind of assistance to China. Sierran Foreign Minister Christopher Rioux had met with Chiang in Nanjing back in June 1927, as he saw Japanese militarism as a threat to Sierra's interests and territories in the region, and promised to seek more support for China's war effort from his government. However, soon after the outbreak of the war Prime Minister Earle Coburn's Royalist government was replaced by a Democratic-Republican administration headed by Poncio Salinas, and the new Sierran government's attention shifted to events in Mexico, the death of King Louis I, as well as other domestic issues. The United Kingdom's leaders believed their colonies in East Asia would be too difficult to defend and sought to avoid antagonizing the Japanese. But events began to change from the spring of 1928. In January of that year, Sierran Ambassador to China Charles Samuel Johnson and his British equivalent Miles Lampson informed Vice Premier Zhang Qun that their countries would provide humanitarian supplies that were needed by the Chinese people. Christopher Roux, as the Leader of the Opposition, had been able to pressure the Salinas government into taking the threat of Japan more seriously as the war escalated.

Vice Premier Zhang visited the Kingdom of Sierra in May 1928 and met with Sierran leaders, including Roux, Salinas, and others, as well as the influential British ambassador to Sierra, the Baron Howard. Their meetings resulted in them agreeing to provide much needed supplies to China and set off the process to build the Burma Road, connecting British India with the Chinese interior. They recognized that supplies by sea, which would arrive in the southern Chinese port of Canton where there was no Japanese presence and be shipped by rail to the rest of China, could be cut off by the Japanese navy in the event of a general war. To that end the construction of a land route would become necessary. The May 1928 meeting between Zhang, Roux, Salinas, and Howard marked the start of a series of diplomatic agreements that would lead to the Quintipartite Pact being signed in July 1929, as a military alliance of their countries along with France and the Ottoman Empire. The Japanese reaction to the initial shipments of supplies to China by Sierra and Britain was quiet as Prime Minister Tanaka and the Imperial Army and Navy leaders were still debating whether or not to pursue the "southern strategy" of expanding into Sierran and European colonies to the south. Within the first six months, China received over 1.1 million tons of supplies through the port of Canton and the Canton–Hankou railway.

The Chinese Communist Party had been formed in 1921, around the time of the beginning of the May Fourth Movement protests against warlordism and foreign imperialism. It had grown from a small group to owning significant territory in the remote Shaanxi province, after having taken advantage of peasant revolts against the local corrupt authorities and generally against the warlords. Thus the CCP began establishing a presence in the countryside by 1926, and started to spread its agents throughout many other parts of China. During the height of the Warlord Era in the early to mid 1920s many peasants and local villages began forming self-defense militias and secret societies to protect themselves from marauding warlord armies. The CCP made an effort to win over many of these militias since 1925. As the Japanese advanced into north China during 1927 and 1928, the Communists had infiltrated the countryside and many peasant militias were formed. As a result of Communist guerrilla groups in the rural areas, the extent of Japanese control in much of the region did not go further than major cities and railways.

Hundred Regiments Offensive

Operation Ichi-Go

Operation 5

Aftermath

Civil war in China

See also

- Start-class articles

- Altverse II

- Second Sino-Japanese War

- Wars involving China

- Wars involving Japan

- Anti-Chinese violence in Asia

- Anti-Japanese sentiment in China

- China–Japan military relations

- Invasions by Japan

- Invasions of China

- Fronts of the Great War

- 1920s in China

- 1930s in China

- 1920s in Japan

- 1930s in Japan

- 1920s in Manchuria

- 1930s in Manchuria

- 1920s conflicts

- 1930s conflicts

- Military history of China during the Great War

- Wars involving the Republic of China (1912–1949)

- Pacific theatre of the Great War