India

Republic of India Bharat Ganrajya | |

|---|---|

| Capital | Delhi |

| Official languages | Hindustani, English |

| Demonym(s) | Indian |

| Government | Federal parliamentary republic |

| Legislature | Sansad |

| Rajya Sabha | |

| Lok Sabha | |

| Independence from the United Kingdom | |

• Dominion | 7 August 1939 |

• Republic | 1 January 1951 |

| Currency | Indian Rupee (INR) |

| Date format | dd/mm/yyyy |

| Driving side | left |

| ISO 3166 code | IN |

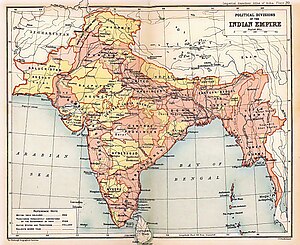

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindustani: Bharat Ganrajya), is a country in the Indian subcontinent. It is the world's x-largest country in land area, the world's most populated country, and most populous democracy. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the south, the Arabian Sea on the southwest, and the Bay of Bengal on the southeast, it shares land borders with Iran to the west, China to the north; and Burma to the east. India is close to the Maldives in the Indian Ocean, and its Andaman and Nicobar Islands have maritime borders with Thailand, Myanmar, and Indonesia.

No later than 55,000 years ago, modern people (an early variant of Homo sapiens) arrived on the Indian subcontinent from Africa. Their lengthy occupancy, which began in various forms of seclusion as hunter-gatherers, has resulted in an extraordinarily varied area, second only to Africa in terms of human genetic diversity. Settled life first appeared on the subcontinent 9,000 years ago on the western borders of the Indus river basin, gradually developing into the Indus Valley Civilisation of the third millennium BCE. By 1200 BCE, an early version of Sanskrit, an Indo-European language, had spread into India from the northwest, becoming the language of the Rigveda and documenting the birth of Hinduism in India. In the northern and western parts of India, an archaic form of Sanskrit replaced the Dravidian languages. By 400 BCE, caste stratification and exclusion had evolved within Hinduism, simultaneous to the birth of Buddhism and Jainism, which declared social systems unrelated to heredity. The loose-knit Maurya and Gupta empires centred in the Ganges basin arose from early political consolidations. A wide range of innovations characterized this age. The deteriorating status of women and the integration of untouchability into an organized system of religion also occurred during this period. The Middle countries of South India introduced Dravidian-language scripts and religious traditions to Southeast Asian kingdoms.

Christianity, Islam, Judaism, and Zoroastrianism established themselves on India's southern and western coastlines in the early mediaeval era. Muslim forces from Central Asia regularly invaded India's northern plains, eventually creating the Delhi Sultanate and entangling northern India in the cosmopolitan networks of mediaeval Islam. The Vijayanagara Empire established a long-lasting composite Hindu culture in southern India in the 15th century. Sikhism arose in Punjab, opposing institutionalized religion. In 1526, the Mughal Empire ushered in two centuries of relative calm, leaving behind a legacy of brilliant architecture. The British East India Company progressively expanded its authority, transforming India into a colonial economy while simultaneously strengthening its sovereignty. British Crown rule began in 1858. The rights promised to Indians were gradually granted, technical advances were made, and ideas about education, modernity, and public life took hold. A pioneering and influential nationalist movement arose in the late 19th century which helped consolidate the idea of India as a united nation and was responsible for the end of colonial rule by continuously and non-violently pushing for major reforms which ended with the British Indian Empire being transformed into the self-governing Dominion of India. The period of Dominion-hood lasted till the end of 1950, when India adopted a Republican constitution, completely severing its ties with the British Empire.

Etymology

According to the Oxford English Dictionary (third edition, 2009), the name "India" is derived from the Classical Latin India, a reference to South Asia and an uncertain region to its east; and in turn derived successively from: Hellenistic Greek India ( Ἰνδία); ancient Greek Indos ( Ἰνδός); Old Persian Hindush, an eastern province of the Achaemenid empire; and ultimately its cognate, the Sanskrit word Sindhu, or "river," specifically the Indus and, by implication, its well-settled southern basin. The ancient Greeks referred to the Indians as Indoi (Ἰνδοί), which translates as "The people of the Indus".

The term Bharat (Bhārat; pronounced, ˈbʱaːɾət), mentioned in both Indian epic poetry and the Constitution of India, is used in its variations by many Indian languages. A modern rendering of the historical name Bharatavarsha, which applied originally to northern India, Bharat gained increased currency from the mid-19th century as a native name for India.

Hindustan (ɦɪndʊˈstaːn) is a Middle Persian name for India, introduced during the Mughal Empire and used, colloquial, very widely since.

History

Ancient India

The earliest modern humans, or Homo sapiens, came on the Indian subcontinent 55,000 years ago from Africa, where they had previously evolved. The earliest modern human remains discovered in India stretch back around 30,000 years. After 6500 BCE, evidence for domestication of food crops and animals, construction of permanent structures, and storage of agricultural surplus appeared in Mehrgarh and other sites in what is now the Baluchistan district. These subsequently evolved into the Indus Valley Civilisation, India's earliest urban civilisation, which flourished in what is now western India between 2500 and 1900 BCE. The civilisation was centred on towns like as Mohenjo-daro, Harappa, Dholavira, and Kalibangan, and dependent on various types of sustenance, participating vigorously in crafts production and wide-ranging commerce.

Many parts of the subcontinent changed from Chalcolithic to Iron Age cultures between 2000 and 500 BCE. The Vedas, the earliest Hindu texts, were written during this time period, and historians have used them to establish a Vedic civilisation in the Punjab area and the upper Gangetic plain. Most historians believe that this time period also included multiple waves of Indo-Aryan migration into the subcontinent from the north-west. During this time, the caste system developed, which established a hierarchy of priests, warriors, and free peasants while excluding indigenous peoples by labelling their activities unclean. Archaeological evidence from this time shows the existence of a chiefdom stage of political organisation on the Deccan plateau. The enormous number of megalithic structures dating from this time, as well as surrounding indications of agriculture, irrigation tanks, and craft practises, suggest a transition to sedentary life in South India.

The minor kingdoms and chiefdoms of the Ganges plain and the northwestern areas had coalesced into 16 large oligarchies and monarchies known as the mahajanapadas by the late Vedic era, about the 6th century BCE. As communities grew in size, non-Vedic religious groups arose, two of which became separate faiths. During the lifetime of its exemplar, Mahavira, Jainism rose to popularity. Buddhism, founded on Gautama Buddha's teachings, drew adherents from all socioeconomic levels except the middle class; documenting the Buddha's life was essential to the beginnings of recorded history in India. Both faiths held renunciation up as an ideal in an age of rising urban affluence, and both developed long-lasting monastic institutions. Politically, by the third century BCE, the kingdom of Magadha had acquired or subdued neighbouring kingdoms to become the Mauryan Empire. The empire was formerly considered to dominate the most of the subcontinent save for the extreme south, but its main territories are now regarded to be divided by huge autonomous zones. The Mauryan monarchs are notable for their empire-building and decisive administration of public life, as well as Ashoka's renunciation of militarism and wide-ranging support of Buddhist dhamma.

The Tamil languaged Sangam literature shows that the southern peninsula was governed by the Cheras, Cholas, and Pandyas between 200 BCE and 200 CE, dynasties that dealt heavily with the Roman Empire as well as West and South-East Asia. Hinduism asserted patriarchal dominance inside the household in North India, resulting in greater female subordination. By the 4th and 5th centuries, the Gupta Empire had established a sophisticated system of administration and taxes on the wider Ganges plain, which served as a model for subsequent Indian kingdoms. Under the Guptas, a reinvented Hinduism focused on devotion rather than ceremonial control began to emerge. This revitalization was mirrored in a blossoming of art and architecture, which found supporters among the urban elite. Classical Sanskrit literature flourished as well, and important breakthroughs were achieved in Indian science, astronomy, medicine, and mathematics.

Medieval India

Regional kingdoms and cultural variety characterise the Indian early mediaeval period, which lasted from 600 to 1200 CE. Harsha of Kannauj, who controlled most of the Indo-Gangetic plain from 606 to 647 CE, was defeated by the Deccan Chalukya king when he sought to push southwards. His successor was defeated by the Pala king of Bengal when he sought to push eastward. When the Chalukyas sought to push southward, they were beaten by the Pallavas, who were in turn challenged by the Pandyas and Cholas, who were even farther south. No ruler of this era was able to establish an empire and maintain stable authority over areas much beyond their primary territory. During this period, pastoral peoples whose land had been destroyed to make room for the expanding agricultural economy, as well as new non-traditional governing elites, were accommodated within caste system. As a result, regional variations in the caste system emerged.

The first devotional hymns were written in Tamil in the 6th and 7th century. They were replicated throughout India, resulting in the revival of Hinduism as well as the creation contemporary languages. Indian aristocracy, both large and little, and the temples they frequented brought a large number of residents to the capital cities, which also served as commercial centres. As India continued to urbanise, temple towns of all sizes began to spring up all over the place. South Indian culture and political systems were transported to territories that formed part of modern-day Myanmar, Thailand, Laos, Cambodia, and Java by the 8th and 9th century. This transmission was carried out by Indian merchants, academics, and occasionally armies; South-East Asians also took the initiative, with many studying at Indian seminaries and transcribing Buddhist and Hindu scriptures into their languages.

After the 10th century, Muslim Central Asian nomadic tribes periodically overran South Asia's northwestern plains, utilising swift-horse cavalry and creating huge armies unified by race and religion, eventually culminating to the formation of the Islamic Delhi Sultanate in 1206. The sultanate was to rule over much of North India and to make many incursions into South India. Although initially inconvenient for Indian elites, the sultanate mainly allowed its massive non-Muslim subjects to practice its own laws and traditions. By repelling Mongol raiders on multiple occasions in the 13th century, the sultanate saved India from the devastation visited on West and Central Asia, paving the way for centuries of migration of fleeing soldiers, learned men, mystics, traders, artists, and artisans from that region into the subcontinent, resulting in the formation of a syncretic Indo-Islamic culture in the north. The sultanate's raids and weakening of South Indian regional rulers prepared the way for the indigenous Vijayanagara Empire. Embracing a strong Shaivite tradition and expanding on the sultanate's military technology, the empire grew to rule most of peninsular India and was to impact South Indian civilisation for a long time.

Early modern India

Northern India, then ruled mostly by Muslim monarchs, again fell victim to the greater mobility and firepower of a new generation of Central Asian warriors in the early 16th century. The resultant Mughal Empire did not extinguish the local communities over which it came to govern. It instead balanced and pacified them through new administrative procedures, and, varied and inclusive governing elites, resulting in more methodical, centralised, and uniform mode of governance. The Mughals unified their far-flung domains via allegiance, expressed through a Persianised culture, to an emperor who had near-divine status, eschewing tribal connections and Islamic identity, notably under Akbar. The Mughal state's economic policies, which relied heavily on agriculture and required taxes to be paid in the well-regulated silver coinage, pushed peasants and artisans into bigger marketplaces. The empire's relative calm for much of the 17th century aided India's economic expansion, resulting in increased patronage of painting, literary forms, textiles, and architecture. During Mughal rule, newly cohesive social groups in northern and western India, such as the Marathas, Rajputs, and Sikhs, developed military and ruling ambitions, which, via collaboration or adversity, provided them with both recognition and military experience. During Mughal administration, the expansion of commerce gave rise to new Indian economic and political elites along the coasts of southern and eastern India. As the empire crumbled, many of these elites were able to pursue and manage their own fortunes.

With the borders between economic and political power becoming increasingly blurred by the early 18th century, a number of European trade enterprises, including the British East India Company, had built coastal outposts. The East India Company's control of the seas, greater resources, and more advanced military training and technology caused it to increasingly assert its military strength, making it appealing to a portion of the Indian elite; these factors were critical in allowing the company to gain control of the Bengal region by 1765 and push out the other European companies. Its greater access to Bengal's wealth, as well as the resulting growth in strength and size of its army, allowed it to annex or subdue much of India by the 1820s. India was no longer exporting produced commodities as it had previously done, but was instead sending raw resources to the British Empire. Many historians consider this to be the onset of India's colonial period. With its economic authority severely limited by the British government and virtually reduced to the status of an arm of British administration, the business began to explore non-economic fields such as education, social change, and culture.

Modern India

Historians believe that the modern era in India began between 1848 and 1885. The accession of Lord Dalhousie as Governor General of the East India Company in 1848 set in motion the adjustments required for a modern state. These included the consolidation and delineation of sovereignty, population surveillance, and citizen education. Technological advancements, such as railways, canals, and the telegraph, were implemented not long after their debut in Europe. However, dissatisfaction with the Company increased during this period, sparking the Indian Rebellion of 1857. The revolt rocked various parts of northern and central India. It undermined the foundations of Company authority, fueling varied resentments and views such as invasive British-style social reforms, punitive land taxes, and summary punishment of certain affluent landowners and princes. Although the revolt was put down by 1858, it resulted in the collapse of the East India Company and the British government's direct control of India. The new rulers declared a unified state and a progressive but restricted British-style parliamentary system while protecting princes and landed gentry as feudal protection against future rebellion. In the decades that followed, public life gradually evolved throughout India, eventually leading to the establishment of the Indian National Congress in 1885.

The advent of technology and agricultural commercialization occurred in the second part of the nineteenth century. Economic failures marked this period, and many small farmers depended on distant markets' whims. The incidence of large-scale famines increased. Despite the risks of infrastructure development funded by Indian taxpayers, there was little industrial employment for Indians. Commercial farming, particularly in the recently canalized Punjab, resulted in increased food output for domestic use. The railway network provided essential famine relief, significantly decreased the cost of carrying commodities, and aided the emergence of the Indian-owned industry.

The nationalist movement emerged during the late 19th and early 20th century demanding greater rights and representation for Indians. The movement came into conflict with the colonial authorities, pushing them for reforms. The 20th century was marked by slow British legislation and the demand for home-rule by the nationalist movement. The 1920s saw the nationalist movement grow rapidly in the face of repressive British legislation due to the revolutionary nationalists. The British responded to the growth of the nationalist movement by granting significant political autonomy to India with the Government of India Act 1931 under the then Labour British Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald. The nationalist movement would continue to demand full Dominion-status for India and agreed to support the British Empire during the Great War in exchange for full Dominion-status. The Great War saw India's active participation with more than two million troops fighting for the Triple Alliance.

The Great War was followed by a series of Round Table Conferences in Britain between the leaders of the nationalist movement and the British government. Through tense negotiations, the Government of India Act 1939 was passed granting India Dominion-status at par with the other British Dominions.

Geography

Biodiversity

Politics and government

Politics

Government

The National Volunteer Corps is a paramilitary force under the Ministry of Internal Affairs. The National Volunteer Corps is tasked with internal security, counter-insurgency operations, counter-terrorism operations, aiding provincial police forces, protection of important infrastructure and protection of significant persons. The National Volunteer Corps has an active strength of 573,691, making it one of the largest paramilitary organizations in the world.

The National Frontier Corps is a paramilitary force under the Ministry of Internal Affairs. The National Frontier Corps is India's sole border guarding force. The National Frontier Corps has an active strength of 294,184.

Administrative divisions

India is divided into 46 provinces and 3 territories.

Provinces

| State | Vehicle code | Capital | Largest city | Established | Population (2011) | Area | Official languages | Additional official languages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Andhra Pradesh | AN | |||||||

| Arunachal Pradesh | AR | |||||||

| Assam | AS | |||||||

| Awadh | AW | Lucknow | ||||||

| Baghelkhand | BA | |||||||

| Balochistan | BL | Quetta | ||||||

| Bundelkhand | BU | |||||||

| Chattisgarh | CH | Raipur | ||||||

| Chattogram Pradesh | CP | Chattogram | ||||||

| East Bengal | EB | Dhaka | ||||||

| East Punjab | EP | |||||||

| Goa | GO | Panaji | ||||||

| Gujarat | GU | |||||||

| Harit Pradesh | HA | Agra | ||||||

| Haryana | HR | |||||||

| Himachal Pradesh | HI | Shimla | ||||||

| Jammu and Kashmir | JK | Srinagar | ||||||

| Jharkhand | JH | Ranchi | ||||||

| Kerala | KE | Thiruvananthapuram | ||||||

| Khyber Pakhtunkhwa | KP | Peshawar | ||||||

| Kongu Nadu | KN | Coimbatore | ||||||

| Madhya Pradesh | MP | |||||||

| Magadh | MG | |||||||

| Maharashtra | MH | Mumbai | ||||||

| Manipur | MN | Imphal | ||||||

| Maru Pradesh | MR | |||||||

| Mithila | MI | Purnia | ||||||

| Mizoram | MZ | Aizawl | ||||||

| Nagaland | NA | Kohima | ||||||

| North Bengal | NB | |||||||

| North Punjab | NP | Lahore | ||||||

| North Karnataka | NK | |||||||

| Odisha | OD | |||||||

| Purvanchal | PU | Varanasi | ||||||

| Rajasthan | RA | |||||||

| Saurashtra | SU | |||||||

| Sikkim | SI | Gangtok | ||||||

| Sindh | SN | Karachi | ||||||

| South Punjab | SP | Multan | ||||||

| South Karnataka | SK | |||||||

| Tamil Nadu | TN | Chennai | ||||||

| Telangana | TE | Hyderabad | ||||||

| Tripura | TR | Agartala | ||||||

| Uttarakhand | UT | Dehradun | ||||||

| Vidarbha | VI | Nagpur | ||||||

| West Bengal | WB | Kolkata |

Territories

National Holidays

National holidays are observed in all states and territories of India. These are secular holidays celebrated to commemorate events in the formation of the Indian nation.

| Date | Name | Commemorates |

|---|---|---|

| 11 May | Anniversary of 1857 | Revolt of 1857, known in India as the First War of Independence |

| 25 May | Independence Day | Declaration of Independence and signing of the Treaty of Calcutta |

| 28 August | Republic Day | Adoption of the Constitution of India |

Foreign, economic and strategic relations

Main article: Indian National Armed Forces

The Provisional Government of Free India was established in Japanese-controlled Southeast Asia in 1933 and the Indian National Army was established as the army of the Provisional Government. The Indian National Army was the primary organization responsible for the liberation of India from British rule. The Indian National Armed Forces were formally established in 1938 with the establishment of the Provisional Government. The Indian National Army continued its role as the land-branch of the Indian National Armed Forces and continues be its largest component. The Indian National Army Air Corps was established in 1934 as a branch of the Indian National Army, attempts to reform the Army Air Force into an independent Air Force were resisted by the Indian National Army till 1954, when the Indian National Air Force was established.

The Indian National Navy was established in 1938, following the Treaty of Calcutta, with the aid of the Imperial Japanese Navy. The Indian National Navy started out as an auxiliary force to the larger Imperial Japanese Navy but slowly grew to become a blue-water navy that dominates the Indian Ocean in the 21st century. The Indian National Navy Air Corps was established in 1940 and continues its role as the naval air arm of the Indian National Navy.

Economy

Industries

Energy

Socio-economic challenges

Demographics, languages and religion

Culture

Visual art

Architecture

Literature

Performing arts and media

Society

Education

12 years of primary, lower secondary and upper secondary education are compulsory in India and must take place at registered schools for children belonging to the ages of 4 to 16. Primary education (junior school) comprises Classes 1 to 6, lower secondary education (middle school) comprises Classes 7 to 9, and higher secondary education (senior school) comprises Classes 10 to 12.

National Council of Education

The National Council of Education was established by the Provisional Government to organise and promote education at all levels in independent India. The National Council of Education acts as India’s Ministry of Education. The Chairman of the National Council of Education is appointed by the Prime Minister and is a member of the National Cabinet.

National Technical Institutes

The need for technological development and the existence of a trained-class of engineers and technocrats for the successful and rapid industrialization of the economy of post-Independence India were quickly recognized by the leaders of the Independence movement. The Provisional Government nationalized the existing engineering colleges and created the National Technical Institutes Council, all the existing colleges were renamed and reorganized and provided hefty sums of money for the development of technological research and education in India. 13 existing institutions of technical education were nationalized and converted into National Technical Institutes in 1935. These National Technical Institutes have come to be the premier technical research institutes of India. The admissions to these institutes at the undergraduate and postgraduate levels are conducted through highly competitive national level exams conducted by the National Council of Education.

| S. No. | Name | Location | Originally Established | Formerly |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | National Technical Institute, Madras | Chennai, Tamil Nadu | 1794 | College of Engineering, Guindy |

| 2 | National Technical Institute, Roorkee | Roorkee, Uttarakhand | 1847 | Thomason College of Civil Engineering |

| 3 | National Technical Institute, Pune | Pune, Maharashtra | 1854 | College of Engineering, Pune |

| 4 | National Technical Institute, Calcutta | Kolkata, West Bengal | 1856 | Bengal Engineering College |

| Bengal Technical Institute | ||||

| Bengal Tanning Institute | ||||

| 5 | National Technical Institute, Dhaka | Dhaka, East Bengal | 1876 | Ahsanullah School of Engineering |

| 6 | National Technical Institute, Patna | Patna, Magadh | 1886 | College of Engineering, Bihar |

| 7 | National Technical Institute, Bombay | Mumbai, Maharashtra | 1887 | Victoria Jubilee Technical Institute |

| 8 | National Technical Institute, Bangalore | Bengaluru, South Karnataka | 1917 | College of Engineering, Bangalore |

| 9 | National Technical Institute, Banaras | Varanasi, Purvanchal | 1919 | Banaras Engineering College |

| 10 | National Technical Institute, Kanpur | Kanpur, Awadh | 1920 | Harcourt Butler Technological Institute |

| 11 | National Technical Institute, Karachi | Karachi, Sindh | 1921 | Prince of Wales Engineering College |

| 12 | National Technical Institute, Lahore | Lahore, North Punjab | 1921 | Punjab Engineering College |

| Mughalpura Technical College | ||||

| 13 | National Technical Institute, Dhanbad | Dhanbad, Jharkhand | 1926 | Indian School of Mines |

Apart from the National Technical Institutes, the National Universities in each of the Provinces are the premier institutes of higher education for all academic fields not related to technical education. While the number of National Technical Institutes has been limited, the number of National Universities has grown, with each Province having its own Provincial National University, which is run in cooperation with the National Government.

Clothing

Cuisine

Sports and recreation

See also

| This page uses material from the Wikipedia page India, which is released under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License (view authors). |

- Start-class articles

- Altverse II

- India

- Countries in Asia

- English-speaking countries and territories

- Federal republics

- Former British colonies and protectorates in Asia

- G20 nations

- Hindi-speaking countries and territories

- Member states of the League of Nations

- South Asian countries

- States and territories established in 1933