Tondo

Tondo 通多國 or 通多 Tondokuk or Tondo | |

|---|---|

|

Flag | |

|

Motto: 敬虔,人類,環境和民族主義 "Maka-Diyos, Maka-Tao, Makakalikasan at Makabansa" "For God, People, Nature and Country" | |

Location of Tondo in Southeast Asia | |

| Capital and largest city | Manila |

| Official languages | Tagalog, English |

| Religion | Roman Catholicism, Islam, Buddhism |

| Demonym(s) | Tondolese |

| Government | Unitary semi-presidential constitutional monarchy |

• Empress | Victoria of Tondo |

| Rodrick Toh | |

| Legislature | Parliament |

| Senate | |

| House of Commons | |

| Independence from Sierra | |

| May 8, 1942 | |

| June 6, 1946 | |

| February 2, 1990 | |

| Area | |

• Total | 1,043,330 km2 (402,830 sq mi) (28th) |

• Water (%) | 0.61% (inland waters) |

| Population | |

• 2020 estimate | 157,846,016 (7th) |

• 2015 census | 150,781,444 |

• Density | 153.8/km2 (398.3/sq mi) (76th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2020 estimate |

• Total | $4.892 trillion (6th) |

• Per capita | $30,991 (43rd) |

| GDP (nominal) | 2020 estimate |

• Total | $3.424 trillion (7th) |

• Per capita | $21,693 (37th) |

| Gini (2015) |

38.5 medium |

| HDI (2019) |

very high · 36th |

| Currency | Tondolese dollar (TND; TD$) (TND) |

| Time zone | UTC+8 (Tondolese Standard Time) |

| Date format |

mm-dd-yyyy dd-mm-yyyy (AD) |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +2 |

| ISO 3166 code | HN |

| Internet TLD | .hn |

Tondo (![]() listen) (Tagalog: 通多, Tondo), is an archipelagic country in Southeast Asia. Situated in the western Pacific Ocean, it consists of more than 8,000 islands, which can be divided into four geographic regions (from north to south): Luzon, Visayas, Mindanao, and Borneo. Its location in the Pacific Ring of Fire, alongside its proximity to the equator, renders the country prone to both earthquakes and typhoons; however, it also endows it with abundant natural resources and some of the world's greatest biodiversity. Tondo has an area of approximately 1,043,330 km2 (402,830 sq mi) and a population of more than 150 million. An additional 20 million Tondolese live overseas, constituting one of the world's largest diasporas. The capital and most populous city is Manila, with the surrounding urban agglomeration being the second-most populous in the world, with over thirty million residents. Tondo is bound by the South China Sea to its west, the Sea of Tondo to the east, and the Celebes Sea to the southwest. It shares maritime borders with Champa, North Vietnam, and South Vietnam to the west, China and Japan to the north, Guam and the North Mariana Islands to the east, and Indonesia to the south.

listen) (Tagalog: 通多, Tondo), is an archipelagic country in Southeast Asia. Situated in the western Pacific Ocean, it consists of more than 8,000 islands, which can be divided into four geographic regions (from north to south): Luzon, Visayas, Mindanao, and Borneo. Its location in the Pacific Ring of Fire, alongside its proximity to the equator, renders the country prone to both earthquakes and typhoons; however, it also endows it with abundant natural resources and some of the world's greatest biodiversity. Tondo has an area of approximately 1,043,330 km2 (402,830 sq mi) and a population of more than 150 million. An additional 20 million Tondolese live overseas, constituting one of the world's largest diasporas. The capital and most populous city is Manila, with the surrounding urban agglomeration being the second-most populous in the world, with over thirty million residents. Tondo is bound by the South China Sea to its west, the Sea of Tondo to the east, and the Celebes Sea to the southwest. It shares maritime borders with Champa, North Vietnam, and South Vietnam to the west, China and Japan to the north, Guam and the North Mariana Islands to the east, and Indonesia to the south.

Excavated stone tools and fossils of butchered animal remains have pushed back evidence of early hominins in the archipelago to as early as 709,000 years; however, the metatarsal of the Callao Man, dated to 67,000 years ago, is the oldest human remnant found in the archipelago. The Aeta (also referred to as the Negritos), constituted the archipelago's earliest known inhabitants. However, they were eventually displaced by successive waves of Austronesians peoples, who in-turn introduced agriculture, weaving, pottery, primitive metallurgy and other Neolithic cultural practices. By the first millennia, maritime settlements known as barangay were established - fostered by early cultural and commercial exchanges with the Malay, Indian, Arab and Chinese civilizations. Over time, these barangay coalesced into chiefdoms or bayan. In the 1500s, Solomon the Great established the Kingdom of Tondo, and with the aid of Portuguese advisors and firearms, unified Southern and Central Luzon. He allied himself with the Portuguese, and eventually converted to Catholicism. During the latter half of the sixteenth century, the nascent Kingdom fought in various wars against foreign adversaries: first Chinese wokou pirates, then the forces of the Sultanate of Brunei, and lastly Spanish conquistadors. Nevertheless, the outcome of the First and Second Castilian Wars ensured Tondo's independence, with various religious orders serving as the liaison between Tondo and authorities in the Spanish East Indies. In 1662, Koxinga invaded Pangasinan and Ilocos; his son Zheng Jing would later succeed in subjugating all of Luzon. The capture of Formosa in 1683 led to the flight of the House of Zhu and remaining Ming loyalists to the Tondolese archipelago, with the Ming Dynasty being nominally reestablished in 1685. The influx of Chinese led to the sinification of Tondo's culture and institutions.

The Southern Ming era was one of peace and prosperity. Tondo was reorganized as a province of China; for example, the Imperial Residence was officially referred to as the Winter Palace, while the Three Provincial Commissions oversaw public administration instead of the Six Ministries. There was a policy of sinification, with all of Tondo's native inhabitants considered Chinese subjects. Classical Chinese became the language of writing and administration, while Hokkien became the lingua franca; however, the various Tondolese languages remained the vernacular. The native nobility and the institution of the barangay were preserved, with the latter being co-opted as the smallest administrative unit. While the datu retained their land and dependents, and were able to pass down their property and titles along familial lines, the datu fell under the authority of a county magistrate. While the lowland peoples were directly-administered, highland peoples and Muslims were governed through the tusi system. Anti-Chinese rebellions continued until the mid-1700s, though ethnic relations were largely cordial, with frequent intermarriage between the Chinese and the natives. The native nobility formed the vast majority of the landed gentry and dominated the rural economy, while ethnic Chinese dominated commerce and central administration. The de facto capital of Xining (now a part of Manila) became a major trading hub, and the archipelago was known for its exports of tea, silk, porcelain, and sugar. Due to its precarious position between two hostile powers, Tondo under the Southern Ming embarked on a policy of militarism and expansionism, annexing the Spanish East Indies in the Third Castilian War and mounting failed attempts to retake the island of Taiwan. Tondo thus effectively blocked European colonization of the region for a century. Despite tensions with the Spanish, Tondo remained majority-Christian. Today, 70% of Tondolese are Catholic, with Catholic art and architecture being part of the country's heritage. Nevertheless, Confucian, Taoist, and Buddhist all influenced Tondolese Catholicism beginning this period - to the censure of the Catholic clergy.

Chinese Ascendancy ended with the TBD War (18XX–18XX) and the promulgation of the Tondolese Empire; these events had its roots in the decline of Ming loyalism, reduced enthusiasm for retaking China from the Manchus, and dissatisfaction with minority rule. The proclamation of the Tondolese Empire marked the de jure restoration of native rule. In actuality, there was little change. By the late seventeenth century, most local administration was carried out by the native gentry and the monarchy had already taken strides to distance themselves from their Chinese heritage. Chinese models of governance were retained, while the Chinese minority continued to dominate commerce. Influenced by contemporary nationalist movements in Europe, the Tondolese literati promoted the ideology of Poanhiat (半血) which advanced the belief that the Tondolese nation resulted from the "union of the Malay and Chinese races". Those who identified as "Tondolese" thus distinguished themselves both from pure Chinese and highland tribes and Muslims. Poanhiat Ideology also advanced a revisionist and romantic view of Tondolese history, which downplayed conflict between the Chinese and natives and the role of Ming royalism in establishing the Tondolese state. Starting in the 1860s, Tondo underwent a semi-successful modernization campaign. Nevertheless, Tondo became subject to numerous unequal treaties and was partitioned between the European powers: Borneo was split between the British and the Dutch, the French purchased Basilan, while the Spanish acquired sovereignty over the Zamboanga Peninsula and the port of Puerto Princesa. Frustration with reforms and foreign encroachment led to the Tondolese Revolution, which spawned the short-lived Tondolese Republic. This was followed by the Sierran–Tondolese War (1898–1902/1913), which brought three decades of Sierran rule.

Tondo was organized as the "Sierran East Indies", and was Sierra's largest and most important colony. Sierran rule coincided with continued economic development and the maturation of Tondolese nationalism. About two million Tondolese migrated to Mainland Sierra, being one of the driving forces behind the Sierran Cultural Revolution. The Great War devastated the country, leaving Manila as the second-most damaged Allied city. From 1938 to 1960, Tondo became a protectorate of Japan. During the Second Great War, Tondolese nationalist guerillas successfully liberated much of the archipelago before the arrival of Sierran–British forces. During the Cold War, Tondo was a staunch ally of Sierra and actively-opposed communist movements in Asia. During Konfrontasi, Tondo occupied a portion of Borneo; to this day, Indonesia and Tondo continue to claim jurisdiction over the entirety of Borneo in what is one of the most longest extant territorial disputes. Tondo had a tumultuous experience with democracy, with the "conjugal dictatorship" of Ferdinand and Imelda Ho marked by relative stability and modest economic growth at the expense of numerous civil and political liberties. The Ho family were expelled from the country in the 1990 Jasmine Revolution, which was renowned for its non-violence and setting a precedent for the largely-peaceful Revolutions of 1999–2000.

Over the course of the Manila Miracle (1992–2019), Tondo became the world's fourth-largest economy by both nominal GDP and power purchasing parity. It is the largest economy in Southeast Asia, and the third-largest after China and Japan. It is considered a newly industrialized country (NIC) and an emerging market, though some economic analysts now classify it as an advanced economy. Tondo is a multicultural country with numerous ethnolinguistic groups. It is unique in being the only Christian-majority nation in Asia, though it also has significant Muslim and Buddhist minorities. Tondo is considered a middle power and a regional power, due to its wide-ranging economic projection and growing military capabilities. Tondo is a close ally of Sierra, with the latter ruling the former from 1902 to 1938, and with millions of Sierrans having Tondolese ancestry. Tondo continues to face numerous issues, such as pervasive regionalism, regional economic disparities, resurgent jihadism, and the aftermath of recent natural disasters such as Typhoons Ondoy and Yolanda.

History

Prehistory

Archaic period

- See also: History of Tondo (900–1521)

The early history of Tondo is obscured by the lack of written records. Consequentially, most information is derived from oral history and foreign accounts. The oldest known calendar-dated document in Tondo is the Bai Copperplate Inscription. It is written mainly in Old Malay using the Kawi script, however it also has influences of Sanskrit, Old Javanese, and Old Tagalog - thus indicating that the people of the archipelago had relations with contemporaneous civilizations. By the tenth century at latest, the inhabitants of the Tondolese archipelago were organized into units known as barangay, which were headed by a Datu (Chief). Most barangay consisted of 40–100 families, with a few having a few thousand inhabitants. Some barangay were stand-alone settlements (known as pook), but most coalesced into larger chiefdoms known as bayan (literally "community"). They were headed by a paramount chief, who often adopted foreign titles ("Rajah", "Wang", "Sultan") to bolster their prestige. Society in both Luzon and Visayas consisted of three classes: the nobility (called maginoo in Luzon, and the tumao in Visayas), the freemen (called timawa), and slaves (called alipin in Luzon, and uripon in Visayas). The authority of the Datu rested on his success in military and maritime expeditions and economic stature. Land was held by usufruct - people had a right to use/profit off the land, but they did not own it. The Datu had the right to distribute land amongst his followers and slaves; he also had exclusive access to certain waterways and fisheries.

As of the 16th century, Tondo was sparsely-populated. This was due to chronic inter-barangay conflict and disease. Luzon and Visayas had a total population of 1.6 million, or around 20 people per square mile. Mindanao and Borneo may have had <300,000 and <200,000 respectively. Low population densities prevented the full exploitation of the archipelago's resources, stalling development. In Visayas, the population subsisted on root crops (such as taro and yams) as a relative scarcity in labor and harsh weather rendered wet-rice cultivation uneconomical. In Luzon, both paddy rice and dry rice were cultivated though root crops remained security crops. Asides from the staples, the Luzonese also cultivated coconuts (which they used to make wine and copra), sugarcane, and cotton. There was significant foreign trade. Most Tondolese exports were forest products, such as civet musk, deer hide, wax, and resin. Cotton and pottery were also exported, most notably to Japan. The Pasig Delta was the most densely-populated region in the archipelago, with about 43,000 residents within the confines of modern-day Manila (for a population density of 200 people per square mile). The three most-prominent settlements were Tondo, Manila, and Namayan. Tondo and Manila had a monopoly on Chinese trade. Each year, one or two Chinese junks would visit Tondo's port, carrying goods such as scrap iron, porcelain, and silk. Manila's ships would then sell these wares throughout the archipelago, making a handsome profit.

Sometime in the early 16th century, during the reign of Bolkiah, much of the Philippines fell under the influence of the Bruneian monarchy. Bruneian merchants were said to have refounded Manila as Kota Selurong, and islamicized the local population. The extent to which this population was truly islamicized is debated, as Portuguese records indicated poor knowledge in Islamic doctrine. Concurrent to the spread of Islam in Tondo was the rise of the "Luçoes", who were traders and mercenaries from Luzon. They were sent to fight in places as diverse as Burma, Japan, Brunei, the Malaccas, and Sri Lanka. One prominent Luzon was Regimo de Raja, who was a spice magnate and an administrator in Portugese Malacca; he also headed an international armada which engaged in regional commerce, and helped protect Portugese trading convoys. Luzonians as a group were well-represented within the Portugese colonial administration, as while many were Muslim, they were undividedly-loyal to the Portugese provided they were well-compensated for their services. Luzonians may have participated in the Fernão Pires de Andrade mission to China (1517–1518), as well as future missions to China and Japan.

Formative period

According to oral tradition, an elderly babaylan named Matanda claimed to receive visions; the first and most frequent of which was of a "holy woman" - later understood by Tondolese Christians to be a Marian apparition. Matanda relayed the holy woman's message of peace and unity among the island's people, particularly among the Tagalogs (from taga-ilog, or "from the river") of Southern and Central Luzon. Matanda would later become Rajah Salalila's mentor, whom she prophesized to become the "greatest leader of the Tagalogs". It is said that when Matanda died, her spirit visibly left her body and rose to Heaven together with the holy woman. Afterwards, a voice from the sky addressed Salalila. This account's reliability is sometimes called into question, as it is suspected the account was embellished with Christian motifs following Solomon I's (Salalila's grandson) conversion to Catholicism.

Salalila would become one of Tondo's most important yet enigmatic historical figures: while his background and achievements have been passed down as oral history, many other aspects of his life are scant. As a young adult, Salalila was charismatic and a good orator. He successfully convinced the leaders of Manila, Namayan, and Tondo to confederate together into the Triple Alliance (Sanduguan ng Tatlong Rajah, literally "Blood Pact of the Three Rajahs"). He armed several hundred of his warriors with matchlock's purchased from the Portuguese. While the martial art of arnis would continue to be held in high esteem, the sword (bolo) fell out of favor, and was replaced by the sibat or thrusting spear. Under Salalila's direction, the Triple Alliance expelled Brunei (as noted by Bruneian historical records and corroborated by Chinese annals) and unified Central and Southern Luzon under a true state. Salalila imposed a tribute-tax (alay) on the conquered barangay. He also promulgated the Great Law of the Land (Kataas-taasang Batas ng Lupa), which was a codification of Tagalog customary law as well as an oral constitution which regulated the relationship between the Rajah of Tondo (who was the Pangulo or High Chief), his confederates in Namayan and Manila, and his vassalized Datu. Salalila's conquests and reforms led to the creation of a "feudal" state in Luzon, with the Rajah of Tondo, Manila, and Namayan collecting tribute from vassalized Datu, and the vassalized Datu collecting tribute from smaller Datu. Supreme administrative, judicial, and martial authority were vested in the Three Rajahs. Using the wealth collected from tributes, they were able to surround themselves with a large "court" that included their senior warriors, nobles, babaylan; "regalia keepers" such as custodians of spears, graves, drums, thrones, crowns; as well as cooks, bath attendants, herdsmen, potters, weavers, and musicians.

Salalila's wife, Dayang Ysmeria (according to oral tradition) succeeded him after his death. There was a balance of power between Manila and Tondo, with Namayan being the junior partner. Tondo controlled the alliance's only arsenal (a monopoly which it fought to preserve), while Manila controlled the alliance's port and ships. While the Bruneian's were viewed with suspicion, the Triple Alliance maintained maintained extensive cognatic ties to Brunei as well as the Moro Sultanates. By the time of Spanish contact, the Triple Alliance was ruled by Ache - also known as the "Old Rajah" (Rajang Matanda), Sulayman III, and Lakandula.

Castillian Wars

- Portugese would arm Tondolese with arquebuses and naval guns (native lantaka too few in number)

- Tondolese would win out, due to higher numbers

- Spaniards cannot mobilize much locally, despite superior weapons

- Spanish influence would be limited to Visayas, Mindanao, and several outposts in Borneo

- asides from Puerto Princesa and Zamboanga, and other garrison-towns, Spanish colonization would be limited in scope (meta = far less extensive than irl, but more intensive in said two cities)

- independence of Luzon affirmed

- it would strengthen relations with the Ming to deter Spanish advances

- Sulayman agrees to allow Catholic missionaries, he himself converts to Catholicism, becoming Solomon I

Kingdom of Tungning (1662–1683)

- Main article: Kingdom of Tungning

In 1662, Zheng Chenggong (known in the West as 'Koxinga', which is derived from Guoxingye 國姓爺) invaded the Tondolese archipelago. He invaded the provinces of Ilocos and Pangasinan with little resistance, and promptly settled 30,000 of his soldiers there. The next year however, Zheng Chenggong died due to malaria, with his son Zheng Jing assuming leadership over the scattered Ming royalist forces. In 1664, Zheng Jing defeated a combined Qing-Dutch fleet, allowing him to resume the conquest of the Tondolese archipelago. From 1664–1667, Zheng Jing placed all of Luzon and Mindoro under Chinese rule. Despite the Tondolese armies' better armament (as the majority of them wielded muskets), the lack of roads and inferior navy prevented them from responding hastily to the Chinese threat. The 1665 Battle of Manila ended in a decisive Chinese victory; nevertheless Chinese military tacticians viewed the Tondolese' musket tactics with great esteem - later influencing the Southern Ming's decision to emulate European-style line infantry. The capture of Manila led to Raja TBD accepting the nominal vassalage of the Ming Emperor. As a result, a succession crisis erupted between his three sons, which was later put down with Chinese aid.

From 1662 to 1683, Tondo was under the indirect rule of the Kingdom of Tungning. It was ruled under the tusi system, with the Ministry of War supervising all relations with the Tondolese Raja and his vassal chiefs. While the Raja retained much of his autonomy and powers, he relinquished supreme military command to an appointed military governor. The Chinese encouraged the cultivation of rice and sugarcane, the first to feed the royalist armies, and the second to trade with the Europeans. They also created massive saltworks in order to acquire another source of government revenue. Substantial demographic changes occured with the invasion of Chinese; the population of Pangasinan was displaced, and the natives moved further upriver to occupy the upper Agno basin. Many Ilocanos fled to the Cagayan Valley, where they were free of Chinese rule. These population movements were known as the Great Migration. In addition, intermarriage between Chinese men and native women further changed regions' ethnic composition; some even resorted to bridenapping or wife-sharing due to the lack of marriageable women due to the lopsided gender ratio of the Chinese settlers.

By 1676, the reconquest of mainland China became increasingly a fever dream, and in 1680, Ming royalists were driven off the mainland entirely with the Qing conquest of Xiamen, Quemoy, and the Pescadores. In 1683, the island of Formosa fell to Qing forces, prompting Zheng Keshuang, the remnants of the Ming House of Zhu, and thousands of Han Chinese to evacuate to the Tondolese archipelago. The sudden influx of 200,000 Chinese further aggravated relations with the natives, with the Chinese comprising a slim majority in Pangasinan, while a plurality in Southern Luzon and Ilocos. The coastal city of Manila, which was renamed Xijing ('New Capital') had an initial population of 30,000 inhabitants; this already dwarfed the long-established city of Tondo just a few miles north. A three-way conflict emerged fought between the anti-Chinese natives, and the Chinese split between pro-Zhu and pro-Zheng factions.

Southern Ming dynasty

- Main article: Southern Ming dynasty in Tondo

Establishment on Tondo

By 1683, there was tension between the House of Zheng and the House of Zhu. Already as early as 1676, Zheng Jing largely abandoned the pretense of restoring the Ming Dynasty and even sought peace with the Qing as an autonomous fiefdom. Zheng Keshuang viewed Qing conquest of the islands - just as they did in Formosa - was inevitable, and sought to eliminate the House of Zhu as they were a potential liability. In 1684, Zheng Keshuang declared himself "Prince of Formosa" and accepted Qing suzerainty. He adopted the Manchu queue to symbolize genuine submission to the Qing. This move was widely unpopular, as the adoption of the queue violated the Confucian norm of maintaining long hair. Zheng Keshuang attempted to rally support amongst his former soldiers. At the same time, the House of Zhu reorganized itself under the leadership of Zhu Jincheng, an eleventh-generation of the famed Hongwu Emperor and the grandson of Zhu Shugui, who committed suicide during the Qing takeover of Formosa. Zheng Keshuang attempted to take over Xining, and upon failing to do so, fled to Manila and entrenched himself there. The brief conflict ended the following year, when a 30,000 man force besieged Manila and reduced its fortress.

Zhu Jincheng's victory over Zheng Keshuang, and his subsequesent coronation in Xining led to the nominal reestablishment of the Ming dynasty. Zhu Jincheng adopted the era name Wutai (武泰), meaning "Exalted Martial". While just 21 years old, Zhu Jincheng already attained massive popular support as he embodied the "perfect soldier". His tall, muscular frame and excellent oratory gave him an intimidating aura. As a child, he was educated in the martial arts and rigorously studied the works of Sun Tzu and other famous military tacticians and strategists. While he was an excellent commander, he forbade soldiers under his command from looting and pillaging, or comitting rape. In 1686, Zhu Jincheng married Dayang Luwalhati, the daughter and only surviving child of Raja TBD. The marriage was a strategic one, as he hoped the marriage would ameliorate the poor relations between the native chiefs and the Chinese invaders. Nevertheless, numerous anti-Chinese rebellions would break out, including TBD from 16XX-16XX, TBD from 17XX–17XX, and the last major one in 17XX.

The Dawu Emperor ruled the Southern Ming until his death in 1715. He presided over a multitude of far-reaching reforms. Chinese-style administration was introduced, with Tondo organized as a nominal province of China and all native Tondolese becoming Ming subjects. The archipelago was officially referred to as either 大南 (Dànán / Toalam) - the "Great South", or 大境 (Dàjìng / Tāikéng) - the "Great Frontier". Public administration was handled by the Three Provincial Commissions, with the Six Ministries having a reduced role in governance. Tondo was divided into XX prefectures, which were led by prefects. Prefectures were further divided into departments, which were further divided into counties. The barangay was co-opted as the smallest administrative unit, with the county essentially replacing the bayan. The datu retained lordship over their barangay as well as their land and dependents; they also continued to exercise most of their judicio-administrative powers. The datu also reserved the right to pass down their titles and property to their children or other family membres. The power of the barangay chiefs was checked by an appointed county magistrate, who served triennial terms and was not native to the area. In exchange for their cooperation, barangay chiefs were bestowed Chinese noble titles and tax exemptions. The Great Ming Code became the law, however customary law was applied in personal disputes - thus requiring arbitration from the datu (who was knowledgeable in local customary law) rather than the county magistrate. While lowland peoples were directly-administered, the tusi system previously used in Southwest China was used to govern highland peoples (such as the Igorot and Aeta) and Muslims. They were under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of War, rather than any one of the Provincial Commissions.

In regards to the economy, the Dawu Emperor demanded that all taxes be paid in silver - thus inducing the monetization and commercialization of the economy. There were three types of taxes: the land tax, the commercial tax levied on merchants, and various excise taxes. There was also corvée, which could be regarded as a tax on labor - this however, could be commuted with a head tax. Corvée labor was mainly used in public construction, in shipyards, or in government monopolies. Luzon was a relative backwater prior to the arrival of the Chinese. When the Chinese arrived, they encouraged local datu to cultivate sugarcane and rice for export. Later, tea was grown in the relatively-cool Ilocos and Cagayan regions, while sericulture was encouraged in Central Luzon. Initially, silk and tea were produced to fulfill native Chinese demands; however they were eventually produced for the export trade. Since the quantity of cotton grown was low, most fabrics were made out of abaca (also called Manila hemp) with the fine nipis weave being held in high esteem. In accordance with the government's militaristic policy, government monopolies on iron, salt, munitions, and shipbuilding were established to finance the creation of a large navy and army, which competed not only with Qing China, but the Spanish and the Dutch.

Zhu Jincheng only had two wives. His second wife, Wang Aiguo, died without issue. His union with Zhu Lina produced nine children - but only one son, Zhu Guoliang. Zhu Guoliang was declared his successor early on, as Zhu Jincheng distrusted the collateral branches of the Zhu family. Zhu Guoliang took on the era name Yongtai (永泰) which meant "perpetual peace". The Yongtai Emperor consolidated the Southern Ming's rule over Tondo. He enforced the adoption of Chinese surnames, which facilitated census-taking and tax collection. He also put down several anti-Chinese rebellions. The first was the 1716 Pangasinan Rebellion, which was led by a nobleman named Karandang Liqiang. The rebellion stemmed from the displacement of the Pangasinense people from their ancestral homelands in the Lingayen Gulf. About 40,000 people were involved in the uprising, however the Yongtai Emperor exercised clemency when he pardoned all of them. Other major rebellions were the Lihan Revolt (1721) and the Ilocos Revolt (1725). Anti-Chinese rebellions were caused by resentment towards heavy taxes and the imposition of Chinese culture. Nevertheless, Chinese rule was never seriously threatened as these insurrections were regionalized.

The government was more concerned about external threats. The brief Sino-Spanish alliance in particular was a major cause of concern. Sino-Spanish relations turned hostile with the 1715 condemnation of Chinese ancestral rites and the subsequesent expulsion of Catholic clergy from China. The Kangxi Emperor hoped to mount a campaign against the Southern Ming, but was occupied by the consolidation of Qing rule and died before doing so - his successor, the Yongzheng Emperor, was more conservative and did not view the Southern Ming as a serious security threat. Due to Tondo's majority-Christian population, relations with the Spanish were inevitable. The Yongtai Emperor formalized a policy of tolerance towards Christianity - against the wishes of the country's Confucian scholar-gentry. He removed sections of the Great Ming Code that criminalized the practice of, or conversion to Christianity. He also continued to permit the operation of various Catholic orders in the country. Later, the Yongtai Emperor only allowed Jesuits to operate within Tondo, as they had a permissible attitude towards Chinese Confucian rites and native Folk Catholicism.

Golden Age

- Main article: Tondolese Golden Age

The concept of a "Tondolese Golden Age" is a revisionist one born out of early Tondolese nationalism. This golden age encompassed the reigns of Zhu Longwei, who ruled as the Dawu Emperor, and Zhu Mingyu, who ruled as Empress Tiancewansui. This period was marked by peace and prosperity, as well as acculturation between the Chinese and the native Luzonese and foreign expansion.

When the Yongtai Emperor died in 1736, his son Zhu Longwei ruled as the Dawu Emperor. Just like his grandfather, the Dawu Emperor was the embodiment of a "perfect soldier". The Dawu Emperor promoted a policy of "military first" (先軍政治, Xiānjūn Zhèngzhì). The standing army at the start of Southern Ming was about 30,000; this tripled to about 100,000 with the crackdown of tax evasion and the more effective administration of the lowlands. The Dawu Emperor structured the country's economy around the Southern Ming's military activities. He increased corvée obligations and allocated most laborers to government shipyards or munitions plants. He also allowed peasants to pay taxes in kind, specifically grain and cloth, which were used to feed and clothe soldiers. He encouraged the cultivation of cash crops and manufacturing, as the income gained from this funded the construction of numerous gun foundries, shipyards, and arsenals. His most important reforms were perhaps tactical. He adopted line infantry and trained troops under European infantry tactics. This made the Tondolese Army the most modern in Asia until the late nineteenth century. Other modifications involved changes in standard armament, such as the replacement of the matchlock by the flintlock and the outphasing of polearms entirely. The Dawu Emperor was inspired by European military treatises such as A Discourse of Military Discipline (1634) by Gerat Barry and Dell'arte della guerra by Niccolò Machiavelli, which he acquired from Jesuits in his court. He was also impressed by native Tondolese musket tactics, with his predecessors establishing a "Bird Gun Regiment" comprised exclusively of musket-wielding Luzonian warriors. His reforms proved decisive in putting down highland rebellions and fending the Southern Ming's position against the Spanish and the Dutch.

The 1740s was a time of constant military campaigning on part of the Dawu Emperor. The rapid "modernization" of his armed forces emboldened him to resume conflict with Qing China. However, many of his soldiers remained inexperienced with the use of firearms - whereas native conscripts, which were used as auxiliaries for the most part, had a long-established musket tradition. The 1740 First Taiwan Campaign was a failure, with a storm reducing the 30,000-strong expedition by a third. Southern Ming forces performed poorly due to a combination of low morale, lack of martial discipline, and poor command. Depleted provisions eventually forced the abortion of the campaign - afterwards the expedition's forces retreated to Aparri in Cagayan. Afterwards, the Dawu Emperor incorporated native conscripts as front-line units rather than auxiliaries. Nevertheless, the failure of the First Taiwan Campaign led to doubts of the effectiveness of Emperor Dawu's reforms. The Qianlong Emperor took this as a sign of weakness, and mounted an invasion of Tondo via Pangasinan in 1742. The expedition involved 300 ships and 20,000 soldiers. Despite having less ships, the Southern Ming's use of European artillery proved decisive. The Qing's infantrymen also were ineffective against Southern Ming musket fire. In 1743, the Southern Ming Court saw renewed confidence and embarked on a more successful second expedition to Taiwan. This time, the integrated Southern Ming forces proved much more organized and disciplined. Southern Ming forces invaded the Pescadores in 1744, holding it for a year. The Qing responded to the Southern Ming occupation of Taiwan by dispatching Shi Feihong - the grandson of the famous Admiral Shi Lang, who generations prior defected from the Ming loyalist cause and retook the Kingdom of Tungning. Ironically, Shi Feihong defected to the Southern Ming. Taiwan was occupied until 1753, when it was deemed too much of a financial burden. Until then, the Southern Ming used the island to conduct coastal raids across Southern China - sometimes even abducting prominent officials as ransom, or transporting anti-Manchu refugees to the Tondolese mainland.

In 1748, the Dawu Emperor ordered the invasion of the Spanish East Indies, sparking the Third Castilian War. Visayas and Mindanao were swiftly-conquered. Most of the Spanish population fled to the Caroline Islands, with those remaining massacred. The population of Visayas, which were resettled into colonial reductions in the late 16th century, were placed under direct rule just like Luzon. Like the datus of Luzon, the former cabeza de barangay retained much of their social distinction and their judicio-administrative powers, with the duties and reach of the county magistrate being comparable to the gobernadorcillo. The Hispanicized nobility of Spanish Visayas, the Principala, were forced to adopt Chinese dress. Meanwhile, colonial town squares were destroyed then rebuilt in a systematic effort to extinguish Hispanic culture. Nevertheless, Hispanic culture remained strong in the Zamboanga Peninsula, perhaps enabed by its relative isolation and the influx of refugees from other parts of the former Spanish East Indies. The Dawu Emperor extended his predecessors' policy of tolerance towards Christians by allowing Jesuits to administer religious missions, though other Catholic orders were expelled. Relations with the Spanish were later normalized in 1763, with the Spanish administering the ports of Zamboanga City and Basilan Island under the suzerainty of the Southern Ming.

Like his predecessors, Zhu Longwei had an accomodationist policy towards the native Luzonians. Asides from his native Hokkien, he also acquired Mandarin, Tagalog, Kapampangan, Spanish, and Latin. He held native oral tradition in high esteem, and ordered them to be translated into Chinese. While he encouraged literacy in Chinese, as it was the language of law and administration, he also encouraged literacy in the native languages and the adoption of the Tondozi script, which was standardized during his reign. Nevertheless, the native nobility were dismissive of the Emperor, as he was the son of a mere concubine. This influenced his decision to take his third-cousin, Lakandula Caihong, as his primary wife. As Empress Consort, she exerted a great deal of influence on politics, and served as the government's informal liaison to the native nobility. Despite being the most high-ranking wife and his most favored wife, Lakandula Caihong was regarded poorly by members of the court due to her failure to produce a son. She was also regarded as a negative influence on the Emperor, as she was Christian. Nevertheless, their eldest daughter together, Zhu Mingyu, was the Emperor's favorite child. When she was 22, she was wed off to Zhu Zhangmin, a descendant of Zhu Honghuan (son of the Genyin Emperor) and thus her distant cousin. As unions between two people of the same paternal lineage (clan) were regarded as incestuous, Zhu Mingyu was adopted by her maternal uncle prior and took on the surname of "Lakandula". When Zhu Longwei died in 1753, he willed the throne to Zhu Mingyu's infant son, Zhu Wangfang (b. 1751), who became the Jintong Emperor. As he was not of age at the time, Zhu Mingyu became regent and thus de facto ruler of the Southern Ming.

Zhu Mingyu's newfound powers brought her under the contempt of some members of the court, including her elder half-brother Zhu Bingwen and Zhu Aiguo. Together with their court allies, they orchestrated the 1754 Incident, in which a tree in the Southern Palace supposedly was marked by "the throne has lost heaven's favor". There was panic among the Confucian elite, who attributed the dynasty's apparent loss of the Mandate of Heaven to their tolerance of Christianity and native paganism. Later that year, a mob stormed the Southern Palace in an attempt to overthrow the Empress Regent. Zhu Bingwen, ridden by guilt and fearing the lie could topple dynasty, disclosed the conspiracy to the Empress Regent and her court. Zhu Mingyu had Zhu Aiguo and his extended family executed, while Zhu Bingwen was spared and would become a close ally of his half-sister. Per his suggestion, Zhu Mingyu shared her regency with Zhu Zhangmin. Despite being demoted to a co-ruler, Zhu Zhangmin was a pliable man with little interest in politics. In 1757, both he and the Jintong Emperor contracted malaria and died. While Zhu Mingyu bore two other sons with Zhu Zhangmin, they died in infancy, with her surviving children all daughters. From this year onwards, Zhu Mingyu ruled as Empress Regnant, and adopted the era name of Tiancewansui (天冊萬歲), meaning "heaven-conferred legitimacy". Empress Tiancewansui's reign was never seriously challenged in spite of her sex, as she was still the daughter of an emperor and she declared her intention to bequeath the throne to someone from the line of Zhu Bingwen - thereby ensuring there was an unbroken line of paternal descent.

The reign of Empress Tiancewansui was marked by exuberant wealth and martial splendor. She normalized relations with neighboring European powers, including leasing Zamboanga and Basilan to the Spanish; albeit they remained under Jesuit administration during Ming occupation (1748–1757). While tensions with the Spanish never faded away, the concurrent Seven Years' War sapped Spanish strength. While two of the three past Empress Consorts were Christian, Empress Tiancewansui was a practicing Catholic and the first monarch to be so. Despite this, she observed Confucian rituals, which together with her liberality towards folk Catholicism almost causing her to be excommunicated.

Empress Tiancewansui reduced corvée obligations and allowed peasants to commute them with a capitation tax (which was to be paid in either taels or their equivalent value in cloth or grain). She also hired wage laborers in certain government industries that require skilled labor, though retained the extensive use of corvée labor in sectors such as shipbuilding and iron production. The source of Tondolese wealth as the export trade. She encouraged native peasantry to cultivate cash crops, both native and non-native, on a commercial scale. Restrictions on rent enabled tenant farmers to sell their surplus to local markets. Many peasants migrated into cities, where they became petty merchants and artisans. The acquisition of the island of Negros, which was calqued into Heidao ("Black Island"), bolstered the Tondolese sugar industry. Tea plantations were established in the Cagayan Valley, whose mild weather enabled the cultivation of tea shrubs. Sericulture was practiced by farmers in Central and Southern Luzon, with most peasant households in the region partaking in silk production. The mulberry species used as the naturalized Morus indica, as the Chinese variety was not used to the monsoonal climate and the hot temperatures. Abaca was grown in Bicol, and was used in place of cotton. Ming-style blue and white porcelain was produced, though new designs emerged. Another popular porcelain type was the "Manila glass", which was a product of using European glassblowing methods.

- marriage w/ someone from line of zhu honghuan

- adoption by maternal family prior

- conspiracy in court

- father of emperor is declared co-regnet

- reign as empress dowager (皇太后); birth of son

- conflict w/ qing; brief war

- conflict w/ spanish and dutch

- conquest of borneo

- economic development; development of interior & regions

- trade

Imperial Tondo is traditionally to have reached its apex under the reign of the Zhide Empress (comprised of the characters 至 - meaning "utmost", and 德 - "virtue"). The Zhide Empress was born in 1719, as Hoan Sikat Pengpeng. She was ethnic Chinese (specifically Hokkienese) on her father's side, and ethnic Tagalog on her mother's side. Her father was a poor peddler, while her mother (known only as Lady Sikat in her genealogical records) died early in her childhood. At the age of 16, her father died, and she moved to Manila to become an actress. Hoan Pengpeng's beauty and intelligence enamored the TBD Emperor, who controversially took her in as his wife. Following his death, she ruled as regent for her son; following his death (under suspicious circumstances), she ruled as Empress regnant for nearly five decades until she gave the throne to her grandson in her deathbed. The Zhide Empress proved to be a competent and shrewd administrator, and under her, Tondo won two wars against its traditional enemies of Qing China and Spain.

Despite the Bourbon reforms, Spain's Asian colonies continued to be rather unprofitable. Much of the land was overgrown with jungle (making them unsuitable for plantation agriculture), and due to the region's low population (which probably did not exceed a half a million inhabitants) the Spanish could not mobilize enough labor to convert these lands into farmland. Similarly, Christianization efforts were in vain, as most of the population were crypto-pagans or crypto-Muslims. Asides from the colonial towns and their environs, the majority of the population continued to adhere either to Islam or native animist tradition.

In the mid-18th century, the Spanish became embroiled in the Seven Years War - thus putting their already poorly-defended Asian colonies in a poor defensive position. In 175X, the Zhide Empress discussed the idea of invading Spain's colonies to reunify the archipelago and to expel the Spanish menace once and for all; despite the protests of the Jesuits, she decided to go forth with the plan under the encouragement of Sir. TBD, a British diplomat who was also a member of the Tondolese court. Tondo amassed an army of XX,XXX soldiers and XXX ships - which were armed with cannons bought from the British and Portugese. The Tondolese quickly conquered Visayas and Mindanao, and established their claim to Borneo (which was nominally held by the Spaniards). The cities of Puerto del Rey, Zamboanga, and Pasangen were briefly-occupied by the British; however by the end of the war, it was retroceded to the Spanish without the input of the Tondolese. Hostilities between the Spanish and Tondolese were concluded in the Treaty of TBD (176X), which saw the recognition of limited Spanish sovereignty over the Sulu archipelago and the Zamboanga peninsula, and the continuation of Spanish rule in Puerto del Rey under a lease.

The Spanish did not consider the loss of Visayas and Mindanao a critical loss, as their Asian colonies' main source of income - the trans-Pacific trade, continued unperturbed. The Spanish also did not have to spend money controlling a restive Muslim/pagan majority. However, the withdrawal from the Spanish from the region resulted in many of the colonial towns being deserted, with the few Spanish and mestizos who remained being expelled and resettled in territories leased to the Spanish. The expulsions marked the end of centuries of Spanish rule in the region - with the only testament to Spanish presence being the town centers, which were built in the colonial baroque-style. Some of these deserted towns, however, would form the nucleus of future cities - such as Iloilo, and Sugbu. While freed from Spanish rule, the Visayans and Mindanaoans found themselves under the rule of the sinified, Luzonese elite.

- many of the captured territories saw the reassertion of indigenous culture; nevertheless, the colonial towns survived and served as the core of the new cities

- expulsion of Spaniards and mestizos from areas not controlled by the Spanish (settlement atl was less extensive – being limited to garrison-towns and the two major ports; Mexican elements were assimilated early on and Spanish settlers being segregated from the population)

- return to native dress (though the Spanish style of dress was limited to the elite, and town-dwellers

- in Mindanao, many crypto-Muslims converted back to Islam, but would go into conflict with their new overlords (who are also Christian – albeit Nestorians)

In 176X, the Zhide Empress declared a campaign to 'pacify' the island of Borneo. About 200 junks, and 10,000 troops (half of which were musketeers) were sent to Borneo during the first expedition. They succeeded to take the city of TBD, as a result, the northern half of the island fell to Tondolese rule. The first settlers described Borneo as an island 'full of head-hunters and cannibals', and doubted the viability of a commercial colony on the island. On the second campaign, which occured in the following year, the Tondolese managed to take the ports of Banjarmasin, Pontianak, and TBD.

- 1770s – conquest of Borneo

- Borneo was rich in resources and land; ethnic Chinese settlers were sent there to help develop the economy

- Borneo was administered by a bunch of vassals, which relinquished control over their diplomatic and military affairs to Tondo but otherwise maintained their autonomy

- the arts would flourish:

- export porcelain and glassware (as local demand for porcelain was relatively low)

- baroque painting (very strong religious themes)

- Chinese-style landscape painting and calligraphy

- "earthquake baroque" architectural style emerges

- religious upheaval

During the reign of the Zhide Empress, trade with the British and the Dutch grew rapidly. Tondo's exports included sugar, hemp, tobacco, coffee, and indigo. Tobacco and coffee were introduced by the Jesuits, but these were grown largely for Western consumption (the favored drink in Tondo was tea, due to Chinese influence). Western demand for these commodities changed the social structure of Tondo by fostering economic integration, as well as increasing the power of the landed class and cementing the institution of serfdom. The importance of serfs to Tondo's plantation economy was highlighted in the Serf Act of 17XX, which penalized runaway serfs, vastly restricted their mobility, and allowed their masters to sell their services without land. By 1800, the proportion of serfs rose to 40% - a figure which would stay at that level until the abolition of serfdom in 1870. Tondo's increasing wealth was evident in the growth of its cities. Manila proper (the walled area) grew from 30,000 inhabitants in 1700, to 100,000 by 1750, and to 300,000 by 1800.

Spread of Christianity

Christianity was introduced into the Tondolese Islands during the period of Yuan suzerainty – specifically, sometime during the early 14th century. However, the form of Christianity introduced was Nestorianism, as opposed to the Roman Catholicism practiced today. In addition to emphasizing the split nature of Christ, Nestorians also practiced the Syriac rite as opposed to the Latin rite. Inevitably, many of these early Christians incorporated elements from both native animism and Chinese folk religions (such as the practice of ancestral veneration), despite the early church condemning these as examples of idolatry. By 1500, it was estimated perhaps 10,000 people within the archipelago were Christian – mainly ethnic Chinese trading colonies in the Manila Bay area. The majority of these were members of the Church of the East, though a few were possibly Catholics converted by Franciscan friars.

However, under the influence of the Ming dynasty, which the primordial Tondolese state sought to consolidate its ties with (as a deterrent against European aggression), Christianity became illegal. Christianity nevertheless persisted, as these edicts (as with the majority of laws in the early years) were not enforced. Sporadic localized persecutions did occur – however, this was more prominent among those of East Asian heritage. The vast majority of the populace would not only tolerate Christianity but would be receptive to it due to its attractive doctrines. Under the Treaty of Jolo (which concluded the First Castillian War), the Spaniards were guaranteed the right to proselytize within select ports – most prominently, the capital of Manila. This move effectively legalized Christianity within these regions, and as a result, many crypto-Christians chose to relocate to them. Many Chinese and Japanese Christians also fled to these regions, owing to the general tolerance of Christianity. A combination of these factors was responsible for why Manila became a firmly Christian city by the late 17th century, exacerbated by higher population growth among converts (who had rejected abortion) and the influx of Chinese Christians due to the turbulent Ming-Qing transition.

In 1700, the Church of the East in Tondo was believed to have constituted about 20% of the population. This figure was perhaps 30–50% in Central Luzon. One of the major reasons why the religion was so successful was because missionaries would claim that both Chinese and indigenous cultures had always believed in the Christian God, and therefore, Christianity would represent the "completion" of their faith. By this point, however, the primary form of Christianity practiced had shifted to folk Catholicism. The influence of Spanish missionary groups had led to the near-marginalization of Tondolese Christianity's Nestorian origins. The only major differences between it and Roman Catholicism were a lax attitude to clerical celibacy (permitting the ordination of married men to the priesthood) and the usage of the Peshitta instead of the Latin Vulgate; the Syriac rite was rendered obsolete far earlier. Also, native Tondolese mythology and some rituals remained. Confucian beliefs and terminologies were also sometimes used in the interpretation of Catholic doctrine – which was encouraged by the Jesuits. In spite of their theological convergence, it was only until the end of the Third Castillian War and the church's prohibition of Confucian-style ancestral veneration (in according to the papal bull), did a sui iris communion with the Roman Catholic Church occur.

Culture

- Main article: Culture of Tondo under the Southern Ming

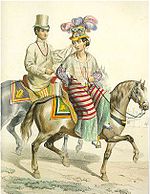

More than a century of Chinese rule changed all aspects of Tondolese culture. The government mandated the adoption of Chinese surnames in 1690, though many nobles retained native surnames such as Sikat ("famous") or Kapulong ("councilor"). The nobility were also ordered to adopt Chinese dress and to abandon native body modification practices such as tattoing and teeth blackening; while these orders did not apply to the native peasantry, by the mid-1700s, Chinese dress replaced native dress in the lowlands. Tondolese cuisine incorporated many dishes, cooking methods, and ingredients from Hokkiennese cuisine. Chinese tea ceremony was also introduced. These changes also led to the cultivation of non-native crops, for example tea in the relatively cool, mountainous regions of Ilocos and Cagayan, and of mulberry in Central Luzon. The Southern Ming also introduced Chinese building techniques and urban planning; prior to Southern Ming rule, construction materials were light, with the exception of forts and Tondolese–Portuguese architecutre (which developed and were found in coastal areas most involved in trade with Europe).

Despite this, native cultural influences still persisted. Native languages continued to be the vernacular, with Tondoji - a modified form of cursive script - being used to write Tagalog. Native attitudes mediated Chinese patterns of kinship, nuptiality, and gender relations. Women were prominent in public life, with female nobility patronizing the arts, public events, and local projects and initiatives. Women also owned, inherited, and managed land independent of their husbands or male relatives. Zhu Mingyu even ruled as monarch, initially as regent (1753–1760), and later as Empress Tiancewansui (1760–1802). The institution of the Chinese clan was not important, rather there was an emphasis on the extended family as a whole. Both sons and daughters inherited property, and matrilocal marriages in where the groom would be formally adopted and take on the name of his wife, were more prevalent than in other regions of China (perhaps comprising a third of all marriages).

Empire of Tondo

Manila War

Decline

Modernization

In the early 19th century, the Dutch East India Company began to settle the southern coast of Borneo, which was sparsely-populated at the time.

- beginnings of opium crisis

- was ignored

- Sultan of Brunei is pressured into giving land to Thomas Brooke

- to avoid offending the British – one of their main trading partners, Tondolese accept this

- Thomas Brooke founds the Raj of Sarawak; it becomes a separate vassal under (nominal) Tondolese suzerainty

- Sarawak Raj would grow at expense of Bruneian Sultanate, due to territorial concessions

- only in 1888 would it become British territory

- Dutch–Tondolese War (of TBD)

- a Dutch squadron would defeat a numerically-superior Tondolese force (comprised of outdated ships)

- progressive loss of southern terrritories:

- southern Borneo (Tondolese vassals) to the Dutch

- rest of Sarawak to the White Rajahs (British protectorate starting 1888)

- Brunei proper secedes, accepts British protectorate status

- Sabah (from Sulu Sultanate) ceded to the British

- sale of Basilan to the French

- leased territories Puerto Princesa, Sulu Islands, and Zamboanga ceded to Spain

- numerous concessions made to European powers (in Manila Bay Area)

Defeat in the Dutch–Tondolese War of 18XX marked the progressive decline of Tondolese control over Borneo. Humiliating treaties with European powers (known as "unequal treaties") led to the loss of prestige, weakening its sway over the region and its self-image as the true successor of the Ming dynasty.

However, Tondolese statesmen - unlike their counterparts in China or Korea, were quick to realize the importance of Western institutions in consolidating the state's socio-political foundations. Under the guidance of the TBD Emperor, Tondo saw the modernization of its government, economy, and education. Tondo adopted the 18XX Constitution, the first in Asia. It affirmed the sovereign power of the Emperor, and his supreme command over the army and navy. The TBD Emperor also allowed all men and women of age, and of property, the right to vote for public offices. However, only less than 2% of the population (the wealthy) exercised this right, due to general political apathy and a required poll tax. Tondo also adopted a form of the Napoleonic Code, which replaced the Great Tondolese Code (which itself is based on the Great Ming Code).

It became increasingly clear that for Tondo to modernize, it needed to also westernize. The government compelled the nobility to adopt Western attire and for males, to cut their top-bun - instating a hefty tax on those who refused to. In order to distance itself from its Chinese roots, the government renounced Confucianism as its official ideology. While imperial examinations continued to be held, its content emphasized modern legal and political theory, rather than Confucian canon. This ultimately resulted in widespread cheating and a low passing rates (as the test candidates knew almost nothing about Western social and political systems), and imperial examinations were abolished altogether in 185X. In 184X, the TBD Mission was sent to Europe - primarily France and Spain. The mission traveled Europe in hopes of learning more about its social and economic systems, so they can be replicated in Tondo. In order to educate the populace, a public education system was created in 185X and primary education (which spanned six grades) was made mandatory. While school attendance remained low as many poor families only sent their children to school a couple days a week, by 1900, about 85% of the population was literate. The government also invited thousands of Westerners (European and Anglo-American) to teach in Tondo's schools, and to serve as 'government advisors'. The number of 'government advisors' peaked at ~3,000 in the 1870s, and by the time of the program's abolition, there were only 500 government advisors left.

The government also pursued aggressive economic reforms. The Bank of the Tondolese Islands (BTI), was established in 185X. It also began to print a new paper currency, called the Tondolese 'cash' (文). Previously, transactions involving money used either silver taels, or pieces of eight. The land tax and the practice of corvée was abolished; instead, an income tax, a sales tax, and an excise tax on certain goods (such as alcohol and tobacco), were implemented - bringing in the government substansial revenue. The government also reluctantly abolished serfdom in 186X - though to conform to the wishes of the nobility it did not give the serfs land or capital. As a result, most ex-serfs continued to work for their former masters under a system of sharecropping (which remained the dominant form of land tenure until the 1950s).

In 185X, the government opened all Tondolese ports to foreign trade - not just Manila. As a result of this openness and the oepning of the Suez Canal (halving the travel time from Europe to Tondo), foreign trade boomed. Despite the government's effort to establish a modern capitalist economy, Tondo continued to be a typical plantation economy characterized by minimal manufacturing and a large landholding elite. Tondo's exports were dominated by four products: sugar, abaca (also called 'Manila hemp'), tobacco, and coffee. Sarawak, a Tondolese vassal until 188X, was also a leading producer of peppers and natural rubber. Apart from cotton, Tondo imported little from overseas - resulting in a substansial trading surplus. By 1898 - at the eve of the Tondolese Revolution, Tondo had a per capita GDP (in 1990 Geary-Khamis dollars) of $1,050 - the highest in Asia. Tondo's wealth was evident in the greater number of infrastructure projects it had undertaken during the 19th century, which put its economy and standard of living far higher than its Asian neighbors and even some European countries at the time. This included a railway system in Luzon (18XX), a tramcar network for Manila (18XX), and Asia's first steel suspension bridge (18XX). The government also undertook 'beautification' projects, most prominently in Manila, wehre they constructed Western-style edifices and restored the older portions of the city. Underpinned by this peace and prosperity, the population boomed: in 1800, the population was 7.5 million; by 1900, it was 30 million.

Despite this, Tondo's territorial contraction continued. In 184X, the White Rajah's forced the Tondolese government to increase the territory given to them. Under British pressure, the TBD Emperor acceded to this demand. Tondo's borders remained stable until the 1860s, when the French pressured Tondo to give up the island of Basilan. Tensions culminated in the Franco-Spanish Expedition of 186X, resulting in Tondo's defeat. The Treaty of Zamboanga (186X) saw the island of Basilan placed under a Franco-Spanish condominium (later becoming fully French), and the ports of Puerto del Rey and Zamboanga City placed under direct Spanish rule. Humiliated by this defeat, the already-old TBD Emperor abdicated and placed his son TBD Lakandula, onto the throne. He adopted the regnal name 'Kaiming' (开明), which meant 'enlightened'. The Kaiming Emperor continued his father's reforms, but emphasized addressing Tondo's military deficiencies. He ordered the establishment of the Manila Arsenal in 186X, and later, the Lingayen Arsenal in 187X. Matchlock muskets were replaced by modern breachloading guns (such as the Dreyse needle gun) and repeaters; initially these were imported, by later on Tondo began domestic production. Tondo also began buying Western ships, eventually producing its own. Backed by British and Anglo-American technical expertise and guidance, the Imperial Tondolese Navy or 'Manila Fleet' would become the ninth-largest navy by tonnage by the 1890s (and second-largest in Asia after the Beiyang Fleet). Its two flagships, the pre-dreadnoughts TBD and TBD would be among the two most advance ships at the time of its commissioning.

In 188X, an incident involving a French ship erupted into the Second Franco-Spanish Expedition or the TBD War. While Sabah was occupied by the French and Spanish, the two powers failed to occupy Mindanao and their attempted blockade of the capital was broken by the Manila Fleet. Despite this, international pressure led to Tondo ceding the entirety of the Zamboangan peninsula and Sabah to Spain, and the Sulu archipelago to France. Furtherore, Spanish and French nationals were also conferred additional privileges within Tondo - in regards to extraterritorial rights and trade. The following year, the White Rajahs renounced Tondolese suzerainty and became a British protectorate. With the loss of Sarawak and Sabah, Tondo's presence on Borneo was ended for nearly a centurty - with Tondo only regaining Borneo in the Konfrontasi. The Madrid Accords (188X) would finalize the division of Borneo between the British, Dutch, and Spanish, and also lead to the mutual recognition of their interests in Tondo.

While Tondo's territory was smaller, the Tondolese state was more centralized and stronger than ever. Nevertheless, the constant feeling of 'national humiliation' lead to the frustration of reforms and rising nationalistic sentiment. Most nationalists were members of a rising class of wealthy men and women educated in Europe, who referred to themselves as the 'Illustrés' (or 'the Enlightened'). Having been educated in Europe, they espoused liberal ideals and engaged in freemasonry. The Illustrés were instrumental in the events leading up to the Tondolese Revolution, by disemminating liberal ideals and inciting revolt against an 'inept' monarchy.

Tondolese Revolution

The final Emperor, the TBD Emperor, rose to power in 188X after the death of his father. However, it is under his reign that Tondo finally crumbled to external pressures.

The Madrid Protocol of 1885, ratified by Spain, France, and Britain,

The Franco–Spanish Expedition to Tondo...

While the British were not directly involved, the North Borneo Company helped the Franco–Spanish effort by providing material aid.

Tondo achieved a tactical victory, decisively defeating the Franco–Spanish forces on land.

The Treaty of TBD, which concluded the war, resulted in the cession of Palawan and Zamboanga (which were already under de facto Spanish administration) as well as the lands of the Sulu Sultanate in the Sulu archipelago and Sabah. France was given the island of Basilan. During this time, the Raj of Sarawak – eager to renounce Tondolese suzerainty – became a protectorate of Britain; the Tondolese reluctantly recognized transfer of power over Sarawak as to not anger the British.

The Madrid Protocol of 1885 was ratified between Britain, Spain, and France. It formally recognized each other's claims in the region, and divided the Tondolese Empire into spheres of influence.

The war was viewed as the coup de grâce to the declining Tondolese Empire, which – in spite of its successful modernization campaigns, and economic growth – was able to assert its independence. The war further frustrated reforms, and ruined public trust in Britain (which came to be viewed as a betrayer).

It was during this time that the nationalist movement reached its height. JR published the Noli Me Tángere (Latin for "touch me not") and Le Filibusterisme (often called "The Reign of Greed") – both of which were originally written in French. These books sharply criticized the monarchy and the government's failures to protect the dignity of the Tondolese people – instead catering to foreign interests. These books are believed to be the reason why the movement gained a distinctly republican attitude, which led to further scrutiny of the movement among the government and the ultraconservative elements of Tondolese society.

- Emperor killed, Imperial family flees

- revolutionary republic thus established

- Spanish–Tondolese War = brief, largely inconclusive

- results in storming of Spanish quarters in Manila, reconquest of ceded territories

- Spain sells rights over territories to Sierra, after Spanish–Sierran War

Tondolese–Sierran War

Sierran East Indies

- Main: Sierran East Indies

The Tondolese archipelago (with the exclusion of Palawan and Basilan, the latter of which remained under French rule), together with the exclave of northeast Sabah, was re-organized into a territorial government under the jurisdiction of the Sierran Bureau of Insular Affairs. The Tondolese Organic Act, promulgated in 1902, served as the territorial constitution; it established an elected lower house, the Tondolese Assembly, as well as the office of Governor–General, who was appointed by Sierra. While the territory was recognized as under the administration of the Kingdom of Sierra, the other participants in the Anglo–Tondolese War, specifically Brazoria and the United Commonwealth, are guaranteed business rights in the regions of Mindanao and Visayas, respectively. To solve the issue of foreign friars, the Sierran government negotiated with the Vatican; the church agreed to the gradual substitution of native Tondolese priests for the foreign friars, and agreed to relinquish ownership over their properties (though with financial compensation). As a result, about 166,000 hectares (410,000 acres) of land – of which, one-half is in the vicinity of Manila – had been transfered to Sierran control, and were eventually resold to Tondolese farmers and land-owners as a bid to weaken the influence of the Catholic Church.

The Tondolese archipelago (with the exclusion of Palawan and Basilan, the latter of which remained under French rule), together with the exclave of northeast Sabah, was re-organized into a territorial government under the jurisdiction of the Sierran Bureau of Insular Affairs. The Tondolese Organic Act, promulgated in 1902, served as the territorial constitution; it established an elected lower house, the Tondolese Assembly, as well as the office of Governor–General, who was appointed by Sierra. While the territory was recognized as under the administration of the Kingdom of Sierra, the other participants in the Anglo–Tondolese War, specifically Brazoria and the United Commonwealth, are guaranteed business rights in the regions of Mindanao and Visayas, respectively. To solve the issue of foreign friars, the Sierran government negotiated with the Vatican; the church agreed to the gradual substitution of native Tondolese priests for the foreign friars, and agreed to relinquish ownership over their properties (though with financial compensation). As a result, about 166,000 hectares (410,000 acres) of land – of which, one-half is in the vicinity of Manila – had been transfered to Sierran control, and were eventually resold to Tondolese farmers and land-owners as a bid to weaken the influence of the Catholic Church.

In 1907, two years following the completion and publication of a census, a general election was conducted for the choice of delegates of the popular assembly; an elected "Tondolese Assembly" constituted the lower house of a bicameral legislature, while an appointed "Tondolese Commission" served as its upper house. Since its formation, the Tondolese legislature would pass annual resolutions (aimed at the Sierran public) expressing the desire for independence; this was partially realized with the passage of the Jones Bill of 1916 (also referred to as the Tondolese Autonomy Act), which were enthusiastically endorsed by Tondolese nationalists led by Manuel L. Quezon and Sergio Osmeña. While a draft which sought to establish independence within a period of eight years was to pending in 1912, it was retracted due to concerns that other European powers (such as Germany) or Japan would instead fill the void left by the Anglo–Americans; as a result, the bill was re-written to emphasize the conditions of independence such as guaranteed Anglo–American support, both in military and foreign affairs. The The Tondolese archipelago (with the exclusion of Palawan and Basilan, the latter of which remained under French rule), together with the exclave of northeast Sabah, was re-organized into a territorial government under the jurisdiction of the Sierran Bureau of Insular Affairs. The Tondolese Organic Act, promulgated in 1902, served as the territorial constitution; it established an elected lower house, the Tondolese Assembly, as well as the office of Governor–General, who was appointed by Sierra. While the territory was recognized as under the administration of the Kingdom of Sierra, the other participants in the Anglo–Tondolese War, specifically Brazoria and the United Commonwealth, are guaranteed business rights in the regions of Mindanao and Visayas, respectively. To solve the issue of foreign friars, the Sierran government negotiated with the Vatican; the church agreed to the gradual substitution of native Tondolese priests for the foreign friars, and agreed to relinquish ownership over their properties (though with financial compensation). As a result, about 166,000 hectares (410,000 acres) of land – of which, one-half is in the vicinity of Manila – had been transfered to Sierran control, and were eventually resold to Tondolese farmers and land-owners as a bid to weaken the influence of the Catholic Church. Tondolese Autonomy Act served as the new constitution of the territory, with its eventual independence becoming a Sierran policy; the Sierran government became responsible for the ensured establishment of a stable democratic government. While the office of Governor–General was maintained, and the King of Sierra – as the head of state – continued to hold the title of "Emperor of the Tondolese", the Tondolese Commision was replaced with an elected senate, reflecting the heightened role of the Tondolese within managing their domestic affairs.

During the First World War, the Tondolese supported the Anglo–Americans (as well as their allies) against Germany; factories and naval bases were constructed. Although the Sierrans joined Japanese forces in the conquest and occupation of German possessions in the Pacific and in China, the Treaty of Versailles stipulated that the Caroline Islands – despite having a Tondolese majority – are to be transfered to the Japanese as a C-class mandate. In spite of this this "setback", the following two decades saw a period of intensive economic growth due to postponed spending, the retooling of munitions and armament facilities into commercial factories, and the instillment of a consumer culture; in 1895, foreign trade had amounted to $655 million, rising to nearly $2 billion by 1930 (and doubling by 1940). Part of this was fueled by continued foreign demand for lucrative Tondolese cash crops, specifically: sugar, abaca, coffee, tobacco, cocoa beans, and copra oil. In addition, the production of cotton and silk fiber was protected by the Sierran government, as it reduced its reliance on imports from the American South and East Asia, respectively. There was also a boom in infrastructural development, with an extensive electric grid, railway system, telephone lines, being built. Additionally, a comprehensive health care system was established, which reduced the mortality rate from all causes – the most important being from various tropical diseases – to a level similar to the United States itself; by 1940, the life expectancy reached 48.3 years. Despite clear socio-economic progress, members of the maginoo (landed gentry), retained their prominence in Tondolese affairs; the lack of comprehensive and meaningful land reform meant the tenant–landlord relationship contiued to dominate the relationship between the upper and lower classes. Serfdom, as well as piracy within the Muslim South and headhunting among the highland indigenes, were suppressed at varying degrees of success, but were not entirely extinguished.

First Great War

- tondo is occupied

- guerilla warfare:

- by end of war, only 18 out of 45 provinces are occupied w/ japanese forces

- 3% of population die - largely due to shortages rather than japanese war crimes

- nevertheless, japanese win in pacific front

Interbellum

The Treaty of Manila (1946) resulted in the end of three decades of Sierran rule over Tondo, establishing the Second Tondolese Republic in its place. The republic was widely unpopular, and in an attempt to bolster public support for the regime, a pleibescite was held for the restoration of the monarchy in 1947. Joseph Lim, who was President of the Second Republic, became first Prime Minister of Tondo. While Tondo's independence was nominally restored, it was forced to give up the ports of Puerto del Principe and Kawit City to Japan - in spite of the treaty also requiring Tondo's neutrality in any trans-Pacific conflict. Furthermore, the government did not implement any land reforms and perpetuated the plantation economy developed during the preceding period - albeit instead catering to the Japanese market. Nevertheless, the 1950s was relatively stable, seeing the continued growth of the economy and a growing sense of national consciousness.

Joseph Lim sought to realign Tondo to Japan, against popular sentiment. In 1950, he banned immigration to Sierra; this ban would only be lifted in 1965, when Tondo was liberated from Japanese influence. It is believed he did this to prevent to prevent the outflow of skilled workers to Sierra, as well as to prevent the entry of "pervasive Western ideas" into the populace. Nevertheless, travel between the two countries continued to be permitted, with Joseph Lim even encouraging Overseas Tondolese (particularly Tondolese-Sierrans) to visit Tondo or even permanently relocate there. Due to this connection, Sierran media and pop culture continued to influence its Tondolese equivalent. In 1953, he took a harder stance against the cultural legacy of Sierran colonial rule by revoking English's status as the second official language. He prohibited the use of English in public spaces, and ended its use in the education system. Furthermore, he commissioned the replacement of loanwords in Tondolese (particularly from Western languages) with words with native etymologies; this was criticized as impractical and were ultimately abandoned after his death.