Italy

Italian Republic Repubblica Italiana (it) | |

|---|---|

|

Anthem: Il Canto degli Italiani (The Song of the Italians) | |

Location of Italy | |

| Capital and largest city | Rome |

| Official languages | Italian (national) |

| Demonym(s) | Italian |

| Government | Federal parliamentary constitutional republic |

| Ernesto di Maggio (PSI) | |

| Sandra Milano (PSI) | |

| Legislature | Parliament Nacional |

| Senate of the Republic | |

| Chamber of Deputies | |

| History | |

• Italian Unification | 17 March 1861 |

• Republic | 14 December 1921 |

• Current Constitution | 28 January 1995 |

| Population | |

• 2020 estimate | 60,317,116 |

| GDP (PPP) | 2018 estimate |

• Total | $2.443 trillion |

• Per capita | $40,470 |

| HDI (2020) |

0.883 very high |

| Currency | Lira (L.) |

| Time zone | Central European Time and Western European Time |

| Driving side | right |

Italy (Italian: Italia), officially the Italian Republic (Italian: Repubblica Italiana) is a country consisting of a peninsula delimited by the Alps and surrounded by several islands. Italy is located in south-central Europe, and it is also considered a part of western Europe. A federal parliamentary republic with its capital in Rome, the country covers a total area of 301,340 km2 (116,350 sq mi) and shares land borders with France, Switzerland, Austria, Slovenia, and the enclaved microstates of the Vatican City and San Marino. Italy has a territorial exclave in Switzerland (Campione) and a maritime exclave in Tunisian waters, Lampedusa.

Due to its central geographic location in Southern Europe and the Mediterranean, Italy has historically been home to myriad peoples and cultures. In addition to the various ancient peoples dispersed throughout what is now modern-day Italy, the most predominant being the Indo-European Italic peoples who gave the peninsula its name, beginning from the classical era, Phoenicians and Carthaginians founded colonies mostly in insular Italy, Greeks established settlements in the so-called Magna Graecia of Southern Italy, while Etruscans and Celts inhabited central and northern Italy respectively. An Italic tribe known as the Latins formed the Roman Kingdom in the 8th century BC, which eventually became a republic with a government of the Senate and the People of Rome. The Roman Republic initially conquered and assimilated its neighbours on the Italian peninsula, eventually expanding and conquering parts of Europe, North Africa and Asia. By the first century BC, the Roman Empire emerged as the dominant power in the Mediterranean Basin and became a leading cultural, political and religious centre, inaugurating the Pax Romana, a period of more than 200 years during which Italy's law, technology, economy, art, and literature developed. Italy remained the homeland of the Romans and the metropole of the empire, whose legacy can also be observed in the global distribution of culture, governments, Christianity and the Latin script.

During the Early Middle Ages, Italy endured the fall of the Western Roman Empire and barbarian invasions, but by the 11th century numerous rival city-states and maritime republics, mainly in the northern and central regions of Italy, rose to great prosperity through trade, commerce and banking, laying the groundwork for modern capitalism. These mostly independent statelets served as Europe's main trading hubs with Asia and the Near East, often enjoying a greater degree of democracy than the larger feudal monarchies that were consolidating throughout Europe; however, part of central Italy was under the control of the theocratic Papal States, while Southern Italy remained largely feudal until the 19th century, partially as a result of a succession of Byzantine, Arab, Norman, Angevin, Aragonese and other foreign conquests of the region. The Renaissance began in Italy and spread to the rest of Europe, bringing a renewed interest in humanism, science, exploration and art. Italian culture flourished, producing famous scholars, artists and polymaths. During the Middle Ages, Italian explorers discovered new routes to the Far East and the New World, helping to usher in the European Age of Discovery. Nevertheless, Italy's commercial and political power significantly waned with the opening of trade routes that bypassed the Mediterranean. Centuries of rivalry and infighting between the Italian city-states, such as the Italian Wars during the 15th and 16th centuries}}, left Italy fragmented and several Italian states were conquered and further divided by multiple European powers over the centuries.

By the mid-19th century, rising Italian nationalism and calls for independence from foreign control led to a period of revolutionary political upheaval. After centuries of foreign domination and political division, Italy was almost entirely unified in 1861, establishing the Kingdom of Italy as a great power. From the late 19th century to the early 20th century, Italy rapidly industrialised, namely in the north, and acquired a colonial empire, while the south remained largely impoverished and excluded from industrialisation, fueling a large and influential diaspora.

Divisions between the rich and poor only grew deeper as economic collapse preceded an Italian violent uprising by socialists and Landonist groups, exiling the King and many members of the bourgeoisie. Declaring a republic, these groups solidified into the Democratic Republic of Italy under the leadership of Benito Mussolini and Giuseppe Calò. Following Landonist revolution, Italy became one of the leading Landonist countries in Europe, alongside Spain. As a member of OMEAD and the Landintern, it played a significant role during Cold War tensions. In 1995, the Landonist government adopted electoral and political reforms that allowed the emergence of a multi-party system and increased democratization. The Socialist Party of Italy (PSI) continues to dominate contemporary Italian politics, in what has been described as a dominant-party system.

Italy is a developed market and a great power; it has the fifth-largest economy in Europe by nominal GDP and the fourth-largest by GDP (PPP). It has a very high standard of living and ranks highly in longevity, health, education, and quality of life. It plays a major role in regional and international politics. It is a member of the European Community and a member of a number of international institutions including the League of Nations, the Organization for Mutual Economic Assistance and Development, the G20, and many more. It is also a leading innovator and historic contributor in various fields including cuisine, fashion, art, music, literature, philosophy, architecture, sports, cinema, and science and technology. It has the world's largest number of World Heritage Sites and is the sixth-most visited country in the world.

Etymology

The etymology of the name "Italy" has been the subject of extensive research and reconstruction by linguists and historians. Various hypotheses have been proposed. One popular theory posits that Italy derives from the word Italói, an Ancient Greek term used to refer to a Sicel tribe that inhabited the tip of the Italic Peninsula after crossing the Strait of Messina. The ancient Greeks who settled present-day Calabria and intermarried with the locals referred to themselves as the Italiotes. These people are noteworthy for worshipping the simulacrum of a calf or vitulus in Latin. It is for this reason, it is believed the ancient Greeks borrowed the term Víteliú from the Oscan language, which means "land of calves". Coins bearing the name Víteliú (Oscan: 𐌅𐌝𐌕𐌄𐌋𐌉𐌞) were minted among the Italic peoples, including the Sabines, Samnites, and Umbrians, as an alliance against the Romans in the 1st century BC. In addition, the Greeks noted similar etymological connections between Víteliú and Ouitoulía, the latter being a Greek derivation of the word "Italói" (plural form italós), an Achaean word used to ambiguously describe the Vitulis. The ancient Greek term italós is based on the Italic derivation from the Osco-Umbrian word uitlu, meaning "bull".

Another theory is based on the writings of ancient Greek historian Dionysius of Halicarnassus who claimed that Italy was named after Italus, a legendary king of the Oenotrians, a claim further asserted by Aristotle and Thucydides.

Other theories on the etymology of "Italy" have included proposals that the term was of Greek, Etruscan, or Semitic origins.

According to Antiochus of Syracuse, the term "Italy" was initially used by the ancient Greeks only to refer to the southern portion of the Calabrian Peninsula (then known as Bruttium). However, during his time, the term had since become interchangeable with the concept of Oenotria, thus expanding the definitions of Italy to include much of modern-day Lucania. Gradually, the Greeks began to use the term "Italia" to refer to a steadily increasing region.

Under Roman Italy, Italia became more well-defined. In Cato's Origines, Italia included all of the Italian peninsula south of the Alps. Cato and other Roman authors described the Alps as the "walls of Italy". By 264 BC, Roman Italy expanded to include the entire southern part of the peninsula. The northern part of Cisalpine Gaul also became geographically considered a part of Italy, despite being administered separately initially. This area was later annexed into Roman Italy by the triumvir Octavian as a ratification of one of Caesar's unpublished acts. The islands of Sardinia, Corsica, Sicily, and Malta were later added to Italy by Diocletian in 292 AD, corresponding to the modern definition of the Italian geographic region. Inhabitants within this region were referred to both as Italic and Roman.

Following the fall of the Western Roman Empire, the Kingdom of Italy, under the Osthrogoths, was created. After the Lombards invaded the region, the term "Italia" was used to refer to their kingdom, followed by its successor within the Holy Roman Empire, a kingdom which nominally lasted until 1806.

History

Prehistory and antiquity

The first hominins arrived in Italy 850,000 years ago at Monte Poggiolo. The Homo neanderthalensis is believed, through archaeological discoveries, to have inhabited the Italian peninsula approximately 50,000 years ago during the late Pleistocene. Modern humans did not appear in Italy until the upper Palaeolithic, with the earliest site dated 48,000 years ago in Ripario Mochi. Various archaeological cultures thrived during the Neolithic period, especially during the Copper Age. The ancient peoples of pre-Rome Italy were largely Pre-Indo-European heritage, most of whom belonged to the Italic peoples, although there were also numerous groups of possible non-Indo-European origins as well. The earliest such cultures included the Laterza, Remedello, Rinaldone, and Gaudo cultures, whose presence could be found in the present-day regions of Apulia, Basilicata, Campania, Latium, Lombrady, and Tuscany.

During the Bronze Age, the Polada culture developed in Northern Italy, distinguished by their use of stilt housing, black pottery, and an economy based on agriculture, pastoralism, hunting, and fishing. In Sardinia, the Nuragic civilization formed and were notable for the Nuraghe, large edifices which have been preserved as one of the oldest and largest megalithic surviving structures in Europe. The ancient civilization was composed of seafaring warriors who developed their own trading routes, bronze statuettes, temples, and wells. In Sicily, the cultures of Castellucio and Thapsos were noteworthy, as they showed influence from cultures in the Aegean Sea during the Helladic civilization. Other early and middle Bronze Age cultures throughout Italy include the Palma Campania culture, the Apennine culture, the Terramare, the Castellieri, the Canegrate, the Proto-Villanovan, and the Luco-Meluno cultures.

During the Iron Age, the Villanova culture emerged in Emilia-Romagna, succeeding the Proto-Villanovans. The Villanovans were noteworthy for their cremation practices, where the deceased's ashes were placed in bi-conical urns and buried. They developed agriculture and husbandry, and later specialized in metallurgy, ceramics, and other craftsmanship, indicating that there was some form of social stratification within the culture. The Latial culture over Old Latium represented a growing cultural consciousness among the Latins and were the immediate predecessors of the ancient Romans. Other Iron Age groups included the Golasecca, Fritzens-Sanzeno, and the Camuni.

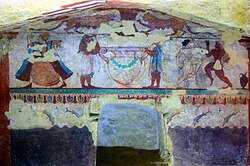

Prior to the rise of the ancient Romans, the Etruscans, a non-Indo-European group, was highly influential in Rome and the Latin world beginning in the 8th century BC. The Etruscans, at their greatest extent, lived in present-day Tuscany, western Umbria, northern Lazio, the Po Valley, Emilia-Romagna, southeastern Lombrady, southern Veneto, and western Campania. The Etruscans organized themselves into small cities, controlled by prominent families. The most powerful and elite families grew wealthy from trading with the Celtic world and the Greeks. The civilisation lasted for nearly a millennium, before assimilating entirely into the Roman civilization by the 1st century BC, following the Roman–Etruscan Wars and the Etruscans' path to Roman citizenship. Other pre-Roman peoples prior to the Roman period included the Ligurians, Lepontii, Insubres, Orobii, Veneti, Sabellians, Falisci, Volsci, Aequi, Piceni, Samnites, Molise, Daunians, Messapii, Peucetii, Lucani, Bruttii, Sicels, Elymians, Sicani, and the Nuragic peoples. Other groups settled in Italy, including the Celtic tribes of the Senones, Boii, and Ligones, as well as the Greeks and Phoenicians in the south and parts of Siciliy and Sardinia.

The Phoenicians established colonies along the coasts of Sicily and Sardinia, some of which developed into urban centers that included the cities of Motya, Zyz (modern Palermo), Soluntum, Nora, Sulci, and Tharros. The Mycenaean Greeks established contacts with and later colonies in Italy between the 2nd and 1st centuries BC. The southern part of Italy and the coast of Sicily were part of Magna Graecia, a region extensively settled by the Greeks and Hellenised natives. The Greek tribes of the Ionians, Dorians, Achaeans all had a presence in the Italian peninsula and they introduced the Italic peoples to democratic expressions of government, as well as Greek art, culture, and philosophy.

Ancient Rome

According to Rome's founding myth, the city of Rome was founded in 753 BC on the banks of the Tiber by the twin brothers Romulus and Remus, who were raised and weaned by a she-wolf. The city was named after Romulus, who according to the legend, killed Remus after the two disputed on the location of the Roman Kingdom. Archaeological evidence suggests that Rome was founded some time during the 8th century BC. Little is certain regarding the history of the Roman Kingdom as no written records have survived from this period. Accounts of this period during later Roman periods were believed to have been based on oral traditions. The Etruscans initially dominated the city as monarchical elites but by the 6th century BC, the Latin and Sabine tribes gained control over the city. Around 509 BC, the Romans, under the leadership of L. Junius Brutus, overthrew the legendary king Tarquinius Superbus. Brutus and several other leaders established the Roman Republic and introduced a system of checks and balances and separation of power. Annually elected officials, known as magistrates, and representative assemblies, formed the basis of the government of the Senate and the People. At the head of the government were the two consuls, who exercised joint executive authority including military command (imperium).

In the 4th century BC, the Roman Republic, which had extended its power beyond Po Valley into Etruria, was attacked by the Gauls. Rome was defeated in 390 BC but the Gauls agreed to a peace settlement with the city whereby the city agreed to give the Gauls 1000 pounds of gold. According to later legend, after the Romans rose up and defeated the Gauls, the Roman general Camillus had remarked to the Gauls that, "With iron, not with gold, Rome buys her freedom." Following their victory, the Romans gradually expanded their territory across the rest of the Italian peninsula, conquering and subduing other peoples including the Etruscans. The Greek colony of Tarentum, was the last city to come under Roman control, falling in 281 BC despite Greek military aid. Roman colonies were subsequently established following military conquest in order to maintain power locally. The concept of socii allowed Rome to assimilate and control most tribes and cities under Roman control. Beginning with the Punic Wars, Rome began its military conquests beyond the Italian peninsula, fighting and subduing its former ally, the Carthaginians. Following the wars and the destruction of Carthage, Rome had taken over the previously Carthaginian possessions of Sicily (which became the first Roman province) and Sardinia, as well as parts of Hispania (the Iberian Peninsula), and parts of North Africa.

Rome's rise to imperial power and dominance in the Mediterranean solidified after it defeated the Macedonian and Seleucid Empires in the 2nd century BC during the Macedonian Wars. During the Late Republic period, there were no significant military threats outside Rome's reach, although internal strife fomented within the Republic itself. In the mid-1st century BC, Gaius Julius Caesar, rose in power amidst Roman political infighting, after forging an alliance between Marcus Licinius Crassus and Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus, who were both rivals vying for power in Rome. The three formed the First Triumvirate. Caesar, as a general, led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars, conquering Gaul and parts of Germany, as well as invading Britain, and cemented his power as dictator after defeating his rival Pompey during a civil war. Caesar's dictatorship signaled the downfall of the Roman Republic and the advent of the Roman Empire. Under Caesar's leadership, he instituted a number of social and political reforms, and most notably, introduced the Julian calendar. His reforms were popular among the people but angered the elites, who conspired against him and then assassinated him during the Ides of March in 44 BC. Following Caesar's death, the Roman Republic plunged into civil wars.

In the wake of Caesar's death, his friend Mark Antony (Marcus Antonius), ruled Rome. After Caesar's great-nephew and adopted heir, Octavian, arrived in Rome, Octavian, Mark Antony, and Marcus Aemilius Lepidus established the Second Triumvirate. The Triumvirate divided the Empire into three part, with Lepidus overseeing Africa, Antony, the eastern provinces, and Octavian with Italia, Hispania, and Gaul. After the Second Triumvirate ended in 32 BC, tensions between Octavian and Mark Antony grew, while Lepidus was forced into retirement following his betrayal of Octavian. Mark Antony moved to Egypt where he became intimately involved with the Egyptian ruler, Cleopatra VII. Following the Donations of Alexandria, Octavian convinced the Senate to declare war on Egypt, starting the War of Actium, the last of the Roman Republic's civil wars. Octavian emerged victorious following the Battle of Alexandria and subsequent suicides of both Antony and Cleopatra. Octavian was then declared the honorific Augustus and became the first Roman emperor, gradually transforming the Republic into the Roman Empire.

The Principate refers to the first period of the Roman Empire from the beginning of Augustus's reign in 27 BC to the end of the Crisis of the Third Century in AD 284. During the Principate, Italy remained the metropole of the provinces while Rome remained the sole, imperial capital. The first two centuries of the Roman Empire saw a golden age of unprecedented peace and stability known as Pax Romana (Roman Peace). Although Rome had bouts of revolts and ongoing conflict with Parthia, the empire enjoyed prosperity and order under Augustus and his successors, the "Five Good Emperors". Italy gained reputation as Domina Provinciarum (Ruler of the Provinces), as well as Rectrix Mundi ("governor of the world") and Omnium Terrarum Parens ("parent of all lands"). At the height of the Roman Empire under Trajan, the empire encompassed 5 million square kilometers, one of the largest empires in world history, and was rich in diversity ethnically, linguistically, culturally, and religiously. The legacy of Rome has deeply influenced Western civilization, which includes the widespread prevalence of the Romance languages including Italian, the Roman numeral system, and the modern Latin alphabet and calendar.

According to Cassius Dio and later historians including Edward Gibbon, the reign of Commodus, followed by the Year of the Five Emperors, and the Crisis of the Third Century (a period of military instability and infighting), marked the decline of the Roman Empire. The Dominate refers to the period of the Roman Empire following the beginning of the reign of Diocletian who stabilized Rome following the crisis. The rise and spread of Christianity, initially a Jewish sect that emerged in the Roman province of Judaea in the 1st century AD, was viewed as a threat by the Romans, and Christians were heavily persecuted, especially under Diocletian. Under Diocletian's orders established the Tetrarchy which had the Roman Empire divided into two: the West and the East, with both headed by a senior emperor titled Augustus and a junior emperor appointed as the Caesar. Following Diocletian's abdication, the Tetrarchy collapsed and order in the Empire was later reestablished under Constantine the Great, who ended the persecution against Christians and became the first emperor to convert to Christianity. Constantine rebuilt Byzantium and renamed it Nova Roma ("New Rome") but the city became better known as Constantinopole.

In the late 4th and 5th centuries, the Western Roman Empire entered a critical stage that led to its fall and collapse. Under the final emperors of the Constantinian and Valentinianic dynasties, Rome faced a number of military defeats against the Sasanian Empire and the Germanic barbarians, as well as the ongoing invasions by other non-Roman peoples. Following the death of Theodosius I, who had further strengthened Christianity, the Empire was formally divided in two between Theodosius's sons: the Western Roman Empire (ruled by Arcadius) and the Eastern Roman Empire (ruled by Honorius). In 408, after the Roman general Stilicho died and failed to reunite the empire and repel the barbarian invasions, the Roman professional army collapsed. During the 5th century, Roman territory was rapidly loss and the city of Rome itself sacked by the Visgoths in 410. The Vandals conquered North Africa, the Visgoths claimed southern Gaul, the Seubi took Gallaecia, the Romans abandoned Britannia, and the Huns under Attila invaded the Empire as well. The barbarian soldier Odoacer became the first King of Italy after he deposed the child emperor Romulus Augustulus, marking the end of the Western Roman Empire. The Eastern Roman Empire continued to survive as the Byzantine Empire for another millennium.

Medieval period

Odoacer ruled Italy for seventeen years under nominal suzerainty of the eastern Roman emperor Zeno. By 489, Zeno decided to oust the Ostrogoths from the Eastern Roman Empire, sending them to Italy. Theodoric the Great defeated Odoacer and became king of Ostrogoths. The Ostrogoths became the aristocratic elites, although their influence over Italy remained minimal as they were Arians and Theodoric maintained Roman laws. In the early 6th century, the Eastern Roman Empire reconquered Italy following the Gothic Wars, drastically devastating the socio-political landscape of the peninsula, sending Italy developmentally back to pre-classical Roman standards. The Roman institution of slavery gave way to serfdom. The Byzantines were unable to maintain complete control over the Italian peninsula, and their withdrawal allowed the Lombards to invade Italy. The Lombards drove out much of the Byzantines from Italy and the Lombards established a kingdom centered in Pavia and divided into dukedoms.

Although the Western Roman Empire had fallen, the Roman Catholic Church and the bishop of Rome (the Pope), remained the most significant and enduring institution in Western Europe. The Church played an increasingly important role in Italy and elsewhere in Western Europe, with the barbarians forced to rely on the Church to exert power and influence. The lack of any other stable institution allowed the Church and its popes to develop their own independent state. The pope aligned themselves with the Carolingians of the Franks for military protection against the Lombards. The Carolingians welcomed the papacy's alliance as they needed justification to oust the Merovingian kings. In 751, after the Lombards attacked Ravenna and abolished the exarchate there, the papacy requested Frankish aid. In 756, the Franks defeated the Lombards and placed central Italy under papal authority, creating the Papal States. The rest of Italy remained under Lombardian control however. In 774, the papacy invited the Franks to invade the Kingdom of Italy. Frankish king Charlemange conquered the Lombards and later, in 800, Charlemagne was crowned emperor of the Holy Roman Empire by the pope, triggering controversy with the Byzantines over the Roman name and title. Charlemagne's conquest led to the complete separation of Northern and Southern Italy politically.

Northern Italy under the Frankish Empire experienced a period of relative stability. As Northern Italy grew closer links with France and Germany, the separation and divide between the West and the East grew more apparent. Following Charlemagne's death in 814, the empire disintegrated under the reigns of his successors. After Charlemagne's son, Louis the Pious died in 840, the Treaty of Verdun divided the empire in 843. Lothair I became emperor and his three sons divided the kingdom between themselves following his death. Northern Italy became known as the Kingdom of Italy under Louis II, Holy Roman Emperor in 839.

Southern Italy, following Charlemagne's conquest, remained in the hands of the Lombards and Byzantines. A number of independent moieties, including the Duchy of Benevento, gained effective independence from both the Byzantines and the Franks. The Duchy of Benevento reached its apex in power during the 830s under Sicard. The duchy faced threats against the Muslim Saracens as well as Greek polities on the peninsula including Sorento, Naples, and Amalfi. The situation in Benevento descended into civil war after Sicard was assassinated in 839.

Following the Beneventan civil war, various independence movements in the cities and provinces occurred. In 852, after the Saracens captured Bari and established an emirate there, Aldechis of Benevento requested assistance Louis II of Italy. Louis II retook Bari and later attempted to establish greater control in the south. The Frankish emperor was imprisoned by Aldechis but was later released to lead the armies against a resurgent Saracen attack.

In 951, King Otto I of Germany married Adelaide of Burgundy, the widow of King Lothair II of Italy. Otto assumed the Iron Crown of Lombrady, thus unifying the thrones of Germany and Italy. In 1960, when Otto's rival to the throne, Berengar II of Italy, invaded the Papal States, the pope invited Otto to conquer the Kingdom of Italy. Otto was then crowned Holy Roman Emperor by Pope John XII, thus making Italy a constituent kingdom of the Holy Roman Empire. As the Holy Roman Emperor remained largely in Germany, Italy lacked a central authority, leaving a power vacuum that the papacy came to fill. Until the 13th century, Italian politics came to be dominated by the relations between Europe's universal powers: the Holy Roman Emperors and the Papacy, centered initially around the Investiture Controversy. The Guelphs and Ghibellines were the dominant factions of the Italian peninsula, with the former supporting the papacy and the latter supporting the Holy Roman Emperors. Meanwhile, portions of Southern Italy during the 9th century came under direct Byzantine rule during the Macedonian dynasty, with the Catepanate of Italy established. By 965 however, the Byzantines lost control over Sicily, which came under Arab control.

The conflicts between the Guelphs and Ghibellines prevented coherent, centralized authority, disrupting the European-styled feudalism pervasive throughout the continent in Italy. Various city-states gained independence in the fall of feudalism and prospered as independent communes and merchant republics. Venice became an international hub of trade and commerce due to its favorable position at the crossroads of the West and the East. Other cities including Milan and Florence also played a role in financial development through innovations in banking, as well as new forms of socioeconomic organization. Numerous other maritime republics formed: Genoa, Pisa, Almafi, Ragusa, Ancona, Gaeta, and Noli. The maritime republics amassed large fleets of ships for military protection and trade, which later played crucial roles in the Crusades. Venice and Genoa grew powerful and influential enough to establish colonies as far as the Black Sea and dominating trade between Western Europe and the Byzantines, as well as the Islamic world. Although the Investiture Controversy was resolved at the Concordat of Worms, the struggle between the Holy Roman Empire and the Papacy fragmented Northern Italy politically. In 1176, several city-states joined the Lombard League, which through the support of the Byzantines, secured the city-states' autonomy from the Holy Roman Empire after defeating German emperor Frederick Barbarossa at the Battle of Legnano.

In the 11th century, Lombard and Byzantine possessions in Southern Italy were conquered by the Italo-Normans. The Normans also ended Muslim rule of Sicily, which had been an emirate. The Normans were able to prevent the Byzantines from reestablishing control over the region and spent several decades conquering and unifying Southern Italy under one polity, eventually becoming a single kingdom first under the House of Hohenstaufen, then the Capetian House of Anjou, and finally the House of Aragon by the 15th century.

The Black Death pandemic of 1348 devastated Italy, killing off nearly one third of its population. The Italian city-states were able to recover economically and socially from the plague however, leading to a resurgence that allowed the development of humanism and the Renaissance to form in Italy and later spread throughout Europe.

By the 14th century of the Late Middle Ages, the thalassocratic maritime republics developed similar systems of government where the merchant class held significant power. Academic and artistic endeavors flourished under the maritime republics, supported by the wealth generated from trade and commerce. The Italian city states were among the first to benefit from the Commercial Revolution, which altered the economic landscape of Europe. Venice and Genoa became producers of fine glass, while Florence became known for its banking, silk, wool, and jewelry. Venice was able to defeat the Byzantines during the Fourth Crusades when it sacked Constantinopole. Marco Polo, an explorer, was able to travel to and return from his journeys through Central Asia and China through the financial support of the Venetians. The first universities in the world also originated in Italy during this time, producing scholars such as Thomas Aquinas. Capitalism, in its infancy, emerged from the banking climate of Florence. However, the region also saw numerous conflicts between the competing city-states, such as the Venetian–Genoese wars. The most powerful city-states absorbed smaller cities: Venice took Padua and Verona; Florence took Pisa; and the Duchy of Milan took Pavia and Parma.

Modern period

The Renaissance began and flourished in Italy during the 14th and 15th centuries. The Italian Renaissance marked the transition in European history from the Late Middle Ages to the Early Modern Period. The Italian city-states became princedoms, representing early forms of modern states. The Italian Wars occurred in the backdrop of the Renaissance as the region was in a state of near constant warfare during the first half of the period. These conflicts were fought mainly through the use of mercenaries led by condottiere on land and large fleets at sea. Florence became the financial and cultural center of Europe. The rise of the Medicis, who controlled Europe's largest bank allowed Renaissance ideals to grow in the city and then spread to neighboring states and cities. Medieval cities experienced revitalization and transformation into early modern cities as Renaissance culture and art proliferated through patronages of dominant families in Italy. Similar prominent families to the Medicis emerged in other city-states: the Visconti and Sforza in the Duchy of Milan; the Doria in the Republic of Genoa, the Loredan, Mocegnio, and Barbarigo in the Republic of Venice; the Este in Ferrara; and the Gonzanga in Mantua. Renaissance ideals were so pervasive, the Papal States and Rome were rebuilt by humanist and Renaissance popes such as Julius II and Leo X. The Italian Renaissance held a lasting impact on European artwork and sculpting for centuries to come and produced numerous well-known artists and architects including Leonardo da Vinci, Brunelleschi, Botticelli, Michelangelo, Raphael, Giotto, Donatello, Titian, Leon Batista Alberti, Andrea Palladio, and Donato Bramante.

Following the First Western Schism which saw the papacy contested and based outside Italy, Pope Martin V returned to the Papal States, restoring Italy's place as the center of Western Christianity. Pope Martin V designated the Medici Bank as the official credit institution of the Papacy and formed close ties with the dominant Italian families as the Church became more involved in secular politics. Due to the electoral manners of popes, the conclaves and consistories became important matters of political intrigue among the courts of Italy since the Church wielded immense power and resources. In 1439, the Council of Florence attempted to reconcile ties between the Roman Catholic Church and the Eastern Orthodox Church which had separated since the Great Schism in 1054. In 1453, Italian forces under Giovanni Giustiniani was sent by Pope Nicholas V to defend the Walls of Constantinopole, although they were unable to prevent the fall of Byzantium to Sultan Mehmed II. Following the fall, many Greek scholars emigrated to Italy, bringing with them texts and ideas that led to a resurgence in Greco-Roman humanism. Ideal cities such as Urbino and Pienza were built by humanist rulers such as Federico da Montefeltro and Pope Pius II.

Leonardo Bruni was the first historian to divide human history into three periods: Antiquity, Middle Ages, and Modernity. The Fall of Constantinople signaled the beginning of the Age of Discovery, at which Italians were at the forefront. Italian explorers and navigators interested in finding alternative routes to the Indies offered their services to foreign monarchies. Notable explorers included Christopher Columbus, who has been credited with discovering the New World in the name of Spain, and providing an opening for the subsequent European conquest of the Americas; John Cabot, in service of England, who was the first European to set foot in "Newfoundland" since the Vikings; Amerigo Vespucci, in service of Portugal, who demonstrated that the New World was not Asia but a previously unknown fourth continent (the Americas are named after Vespucci); and Giovanni da Verrazzano, in service of France, who became the first European to explore the Atlantic coast of North America between Augustinia and the Maritimes.

The fall of Constantinople left significant impacts on Italian politics and society at home. Threatened by the prospect of Turkish expansion, as well as wariness regarding France, the wars in Lombrady came to an end and a defensive alliance in Northern Italy known as the Italic League formed between Florence, Milan, Naples, Venice, and the Papal States following the Peace of Lodi. The league brought forty years of peace and economic expansion in Italy as the alliance established a balance of power between the participant states. Lorenzo de Medici was a notable figure during this period, as an Italic League supporter, and Florence's greatest patron. He prevented the collapse of the Italic League in the aftermath of the Pazzi conspiracy and during the failed Turkish invasion of Italy. However, the Italic League declined and ultimately ended. The League's collapse left Italy vulnerable to foreign ambitions. In 1494, Charles VIII of France invaded the Kingdom of Naples with dynastic claims, triggering the Italian Wars between the Valois and the Habsburgs. Thus, during the High Renaissance, although Italy remained culturally dominant, it remained politically fragmented and became the battleground for European supremacy.

The French initially retreated after the Republic of Venice formed an alliance with Emperor Maximilian I of Austria and Ferninand V of Spain, but returned to invade the Kingdom of Naples after taking control of the Duchy of Milan and establishing a firm alliance with the Papacy. Spain gained control over the Kingdom of Naples from France while France took control over most of northern Italy after defeating the Venetians by the end of the War of the League of Cambrai. Pope Julius II sought to remove foreign presence in Italy and forged an alliance with Switzerland and the Holy Roman Empire. The pope's sudden death resulted in status quo antebellum in 1516 and the new Pope, Leo X, recognized French control over Northern Italy (with the exception of the Venetian republic) and Spanish control over Southern Italy.

Warring resumed in 1521 when Leo and Charles V expelled French forces from Milan, prompting Francis I of France to retaliate and entering Italy himself before he was captured during the Battle of Pavia. Francis was forced to cede French territory to Habsburg Netherlands and later waged a new war after his release, which saw mutinous Landsknecht, alongside Spanish and Italian mercenaries, entering and sacking Rome, and expelling the Medici from Florence. Charles ordered the retreat of his imperial forces from the Papal States and restored the French territory occupied by Habsburg Netherlands, on the condition that the French abandon Northern Italy in the Peace of Cambrai. In 1530, Charles was titled King of Italy by Pope Clement VII and the Medicis were restored to power in Florence.

In 1536, conflict broke out over a dispute over the Duchy of Milan following the death of Francesco II Sforza, which saw France invading Northern Italy and the Spanish invading France. The Ottomans, siding with the French, also participated in the conflict by attacking Genoa. Conflict ceased following the Truce of Nice in 1538, which was brokered by Pope Paul III, and left France with control over most of Savoy, Piedmont, and Artois. The truce however, left the issue of conflicting claims over the Duchy of Milan unresolved.

The 1538 truce was broken in 1542 when Emperor Charles V made his son Philip the Duke of Milan, provoking Francis who still held claims over the duchy. In 1541, after the disastrous Algiers expedition by Charles V, the Ottomans under Sulemain reactivated their alliance with France, allowing the French to renew war against the Habsburgs. The conflict extended beyond Italy as there was fighting in France and the Low Countries, as well as attempted invasions of Spain and England. The conflict ultimately ended inconclusively following the Treaties of Crépy and Ardres.

In 1551, the last so-called Italian War began when Henry II of France declared war against Charles V with the intent of continuing his late father's claims and aspirations towards recapturing Italy. The war saw significant use of gunpowder technology and increased professionalism among soldiers. In 1554, Philip of Spain became King of England and gained the kingdoms of Naples and Sicily from his father, reaffirming Philip's title as Duke of Milan. In 1556, Charles V formally abdicated his throne and split his possessions between his brother Ferninand I (who assumed control over the Holy Roman Empire) and Philip (who gained the remainder of Charles V's possessions, including Spain, its overseas territories and the Spanish Netherlands). The war ended with the Peace of Cateau-Cambrésis, which saw Corsica being returned to Genoa, and the reestablishment of an independent Savoyard state. For the next century, Naples and Lombardy would provide a major source of income and soldiers for the Spanish Army of Flanders during the Eighty Years' War.

Throughout the Renaissance and Age of Discovery, the Papacy remained politically dominant. Aside from its involvement in the Italian Wars, the Papacy was a major force in the Counter-Reformation, which saw major events such as the Council of Trent, the adoption of the Gregorian calendar, the Jesuit China missions, the French Wars of Religion, the Long Turkish War, the Galileo affair, the Thirty Years' War, and the formation of the Holy League during the Great Turkish War. The Papal States and Italians were involved in the European wars of religion and prominent Italians were involved in other Catholic nations including Catherine de Medici, Mary de Medici, Concino Concini, Jules Mazarin, Torquato Conti, Raimondo Montecuccoli, Ottavio Piccolomini, Ambrogio Spinola, and Alexander Farnese.

The Venetians following the Italian wars began to gradually loses its power and holdings in the Eastern Mediterranean to the Ottomans. During the Great Turkish War, the Venetians captured the Peloponnese but the land was ceded back after the end of the Venetian-Ottoman Wars. The Republic of Genoa also gradually lost power.

Following the War of Spanish Succession and the War of the Quadruple Alliance, the Habsburgs became the dominant powers in Lombardy and Southern Italy, although the Spanish were later re-installed in Southern Italy following the War of the Polish Succession which established the House of Bourbon-Two Sicilies. By the end of the 18th century, on the eve of the Napoleonic Wars, Italy had declined considerably as the Age of Discovery was dominated by Western European powers and the Protestant Reformation diminished the powers of the Papal States. Spanish domination had given way to Austrian domination while the Savoyards enlarged their holdings with Sardinia and northwestern Piedmont. The French Revolution greatly influenced political ideals within Italy. In 1796, Napoleon invaded Italy with the French Army of Italy in order to force the First Coalition out of Sardinia and Austria out of Italy. By late 1797, Napoleon signed the Treaty of Campo Formio, which saw the Republic of Venice annexed by Austria, Piedmont annexed by France, and the recognition of the French sister republic of the Cisalpine Republic (composed of Lombardy, Emilia-Romagna, and parts of Tuscany and Veneto). In 1802, the Cisalpine Republic became known as the Italian Republic under the presidency of Napoleon. The Italian Republic was later reorganized into the Kingdom of Italy, in a personal union with the French Empire. The southern half of the peninsula was administered by Joachim Murat, Napoleon's brother-in-law, who was crowned as King of Naples. The 1814 Congress of Vienna restored the situation of the late 18th century, but the ideals of the French Revolution could not be eradicated, and soon re-surfaced during the political upheavals that characterised the first part of the 19th century.

During the Napoleonic era, in 1797, the first official adoption of the Italian tricolour as a national flag by a sovereign Italian state, the Cispadane Republic, a Napoleonic sister republic of Revolutionary France, took place, on the basis of the events following the French Revolution (1789–1799) which, among its ideals, advocated the national self-determination. This event is celebrated by the Tricolour Day. The Italian national colours appeared for the first time on a tricolour cockade in 1789, anticipating by seven years the first green, white and red Italian military war flag, which was adopted by the Lombard Legion in 1796.

Unification

The birth of the Kingdom of Italy was the result of efforts by Italian nationalists and monarchists loyal to the House of Savoy to establish a united kingdom encompassing the entire Italian Peninsula. Most scholars have agreed that the beginning of Italian unification occurred at the end of Napoleonic rule. Following the Congress of Vienna in 1815, the political and social Italian unification movement, or Risorgimento, emerged with the goal of uniting Italy by consolidating the different states of the peninsula and liberating it from foreign control. A prominent radical figure was the patriotic journalist Giuseppe Mazzini, member of the secret revolutionary society Carbonari and founder of the influential political movement Young Italy in the early 1830s, who favoured a unitary republic and advocated a broad nationalist movement. Mazzini's efforts through propaganda helped propel the unification movement forward.

During the early Risorgimento, a number of patriotic songs were created. In 1847, the first public performance of the song Il Canto degli Italiani, the Italian national anthem since 1946, took place. Il Canto degli Italiani, written by Goffredo Mameli set to music by Michele Novaro, is also known as the Inno di Mameli, after the author of the lyrics, or Fratelli d'Italia, from its opening line.

The most famous member of Young Italy was the revolutionary and general Giuseppe Garibaldi, who was renowned for his extremely loyal followers. Garibaldi led the Italian republican movement for unification in Southern Italy. However, the Northern Italy monarchy of the House of Savoy in the Kingdom of Sardinia, whose government was led by Camillo Benso, Count of Cavour, also had ambitions of establishing a united Italian state under a monarchy. In the context of the 1848 liberal revolutions that swept through Europe, an unsuccessful first war of independence was declared on Austria. In 1855, the Kingdom of Sardinia became an ally of Britain and France in the Crimean War, giving Cavour's diplomacy legitimacy in the eyes of the great powers.

In 1860–1861, Garibaldi led the drive for unification in Naples and Sicily (the Expedition of the Thousand), while the House of Savoy troops occupied the central territories of the Italian peninsula, except Rome and part of Papal States. Teano was the site of the famous meeting of 26 October 1860 between Giuseppe Garibaldi and Victor Emmanuel II, King of Sardinia, in which Garibaldi shook Victor Emanuel's hand and hailed him as King of Italy; thus, Garibaldi sacrificed republican hopes for the sake of Italian unity under a monarchy. Cavour agreed to include Garibaldi's Southern Italy allowing it to join the union with the Kingdom of Sardinia in 1860. This allowed the Sardinian government to declare a united Italian kingdom on 17 March 1861. Victor Emmanuel II then became the first king of a united Italy, and the capital was moved from Turin to Florence.

In 1866, Victor Emmanuel II allied with Prussia during the Austro-Prussian War, waging the Third Italian War of Independence which allowed Italy to annexe Venetia. Finally, in 1870, as France abandoned its garrisons in Rome during the disastrous Franco-Prussian War to keep the large Prussian Army at bay, the Italians rushed to fill the power gap by taking over the Papal States. Italian unification was completed and shortly afterwards Italy's capital was moved to Rome. Victor Emmanuel, Garibaldi, Cavour, and Mazzini have been referred as Italy's Four Fathers of the Fatherland.

Kingdom of Italy

The newly formed Kingdom of Italy emerged as a great power which nonetheless faced a number of challenges. Tensions between monarchists and republicans, as well as disparities between Northern and Southern Italy made the existence of the Italian nation-state highly contentious. Another major challenge that Italian political leaders faced was integrating the various political and administrative systems of the previous states. Under the Kingdom of Italy, Italian politics shifted increasingly towards liberalism. The period between the foundation of the Kingdom of Italy and its dissolution in the Italian Revolution of 1918 is thus sometimes referred to as the "Liberal period" or "Liberal Italy".

In April 1861, Garibaldi was elected into the Italian parliament and challenged the leadership of Italy's first prime minister Count Camillo Benso of Cavour and threatened civil war. Two months later, Cavour died and Garibaldi and the republicans became emboldened with revolutionary talk. Garibaldi was arrested in 1862 which further inflamed political unrest.

In 1866, Otto von Bismarck of the Kingdom of Prussia offered an alliance with Italy to Victor Emmanuel III in the Austro-Prussian War. Bismarck promised to allow Italy to annex the Austrian-controlled Veneto in exchange for the alliance. King Emmanuel accepted the terms and the Third War of Italian Independence began although Italy performed poorly against Austria. Italy was able to annex Veneto however due to Prussia's victory against Austria. With the annexation of Veneto, the last remaining territory in the Italian peninsula that had not been integrated into Italy yet was Rome, which was regarded as the natural capital of Italy.

Revolution of 1918

Great War

Post-war period

Cold War

Contemporary history

Geography, climate, and environment

Italy is located in Southern Europe and is also classified as a Western European country. Italy is situated between latitudes 35° and 47° N and longitudes 6° and 19° E. The Italian mainland is roughly coterminous with the homonymous geographical region which includes the entirety of the Italian peninsula that sits south of the Alps and protrudes into the centre of Mediterranean Sea and flanked by the Adriatic to the east; the Ionian Sea, to the south; the Ligurian Sea, the Sardinian Channel, Tyrrhenian Sea, the Strait of Sicily and the Sea of Corsica to the west. In addition to the Italian mainland, Italy includes the island of Sicily and a number of smaller islands in the Mediterranean. Italy also includes two enclaved countries: Vatican City in Rome and San Marino.

Italy's total area is 263,533 square kilometers (101,751 square miles). Italy is topographically varied and more than 30% of the country is mountainous. The Apennine Mountains runs through the majority of peninsula in a northwest-southeast orientation and is the defining geographic feature in the Italian peninsular interior. The Alps defines much of Italy's northern border and includes Mont Blanc (4,810 m or 15,780 ft) which is Italy's highest point. Other notable mountains in Italy include Matterhorn (Cervino; 4,478 m or 14,692 ft), Monte Rosa (4,634 m or 15,203 ft), and Gran Paradiso (4,061 m or 13,323 ft) in the West Alps. In the East Alps, notable mountains include Piz Bernina (4,049 m or 13,284 ft), Stelvio Pass (2,757 m or 9,045 ft), and Marmolada of the Dolomites (3,343 m or 10,968 ft).

Italy is highly volcanic and is situated on the junction between the Eurasian Plate and the African Plate. As a result, Italy is seismically active and occasionally experiences major earthquakes. There are a total of forteen volcanoes of which four are active: Etna, Stromboli, Vulcano, and Vesuvius. The former three are on or off the coast of Sicily while the latter is on the Italian mainland and the only active volcano in mainland Europe. Mount Vesuvius is famous for being the volcano responsible for the destruction of Pompeii, Herculaneum, Stabiae, and Oplontis in the eruption in 79 AD.

Waters

Volcanology

Environment

Biodiversity

Climate

Politics and government

Overview

Italy is a socialist state which features a parliamentary federal republic with a multiparty system. The Italian government is structured accordingly to the Constitution of Italy, which was adopted in 1996. The president is the head of state and is directly elected by the Italian electorate every 5 years. The term of presidency can be renewable unlimitedly. In the Italian order of precedence, the president outranks all other government officials and representatives. The Italian president is responsible for primarily representative and ceremonial functions. Among the most important responsibilities of the president is to appoint and dismiss members of the Council of Ministers (Consiglio dei Ministri), including the prime minister. In practice, the decision to appoint a prime minister or the Council of Ministers is generally done in accordance to whomever is elected or selected by a majority from Parliament. In the case of dismissal, this is usually based on a motion of no confidence or a request by the ruling government. In addition to being the head of state, the president is the commander-in-chief of the Italian military.

The legislative branch comprises the Italian parliament which consists of two houses. Parliamentary sovereignty is asserted by Parliament. The numerically larger of the houses is the lower house: the Chamber of Deputies (Camera dei deputati) consisting of 630 members, while the upper house is the Senate of the Republic (Senato della Repubblica) and consists of senators from each of the 20 provinces and Italians living abroad from overseas constituencies. The head of government is the prime minister, who is elected by parliament and usually comes from the largest faction or party of the governing coalition. The prime minister holds executive power and is responsible for the administrative functions of the state, as well as any responsibilities constitutionally delegated by the president. The prime minister is supported by members of the Council of Ministers, the primary executive organ of the Italian state. Like the prime minister, members of the Council of Ministers are chosen from among members of Parliament. Both members of the Italian parliament and senators are directly elected by Italian voters over the age of 18 according to a system of proportional representation, using the d'Hondt method.

The Italian judicial system consists of several high courts. The Constitutional Court of Italy (Corte costituzionale della Repubblica Italiana) has jurisdiction on matters pertaining to constitutional law. On matters of government auditing, the Court of Audit (Corte dei Conti) has primary jurisdiction. Magistrates from all of the aforementioned courts are elected by members of Parliament and elected to serve on varying terms. The Supreme Court of Cassation (Corte Suprema di Cassazione) is the highest court of appeal pertaining to cases involving penal, civil, and military matters. Each province also have their own high courts and judiciary systems.

Law and criminal justice

The Constitution of Italy is the supreme law of the land. Its purpose is to outline the structure and powers of the government, as well as provide guarantees to basic human rights and other rights afforded to Italian citizens, and other provisions concerning the Italian state. However, Parliament retains absolute sovereignty and thus, any constitutional law can be abrogated by parliamentary statute. Italian law is based on a civil law system which is codified into several codes. The Italian Civil Code is based on codified Roman law which has been modified with elements of Napoleonic code. The Italian penal code is based on a modern update of the penal code first created under the Landonist regime.

The Supreme Court of Cessation is the highest court on criminal and civil cases, and is generally the last court of resort. The Constitutional Court is the highest court on constitutional matters and the conformity of national law. The Constitutional Court can issue non-binding recommendations or consultations to Parliament regarding law revisions or amendments. The Court of Audit is the highest court regarding government accountability and auditing.

Italy is a signatory to a number of international conventions, including the Geneva Conventions and the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons. It is also subject to the judicial purview and oversight of the European Court of Justice pertaining to EC law.

The Italian law enforcement system is divided into four law enforcement agencies at the national level. Polizia di Stato (State Police or PS) is the primary civilian law enforcement agency. It is part of the Ministry of Interior. The PS is responsible for providing policing services to major cities, provinces, and regions, assisting local police, and providing customs enforcement and border security. The Polizia stradale (Traffic Police) is responsible for policing Italy's highways, roads, railways, and airports. The Carabinieri is the national genderarmerie, and is a military force that serves as the senior military corps of the Italian Army. It is also the military police for the Italian armed forces. The Guardia di Finanza is a militarised police force under the Ministry of Finance which is responsible for dealing with counterfeiting, drug smuggling, human trafficking, fraud, and financial crimes.

Italian organised crime has been an issue in Italy since the mid-19th century, especially in Southern Italy. During the Landonist rule, mafia activity was heavily suppressed in Sicily and Campania, although the mafia was able to maintain a foothold in Calabria and Apulia. Emigration from Italy to Anglo-America and elsewhere around the world resulted in international mafia presence. Following the Lily Revolution, mafia presence increased again. The most prominent and famous syndicated criminal organisation is the 'Ndrangheta, based in Calabria. Other notable criminal groups including the Cosa Nostra (the Sicilian Mafia), and Camorra. Despite the prevalence and political infiltration of organised crime, violent crime rates are low relative to Italy's total population.

Political parties

Italy has officially been a multi-party democracy since the reforms of the 1980s. Prior to the reforms, Italy operated as a single-party state in which the Socialist Party of Italy was the sole legal political party. However, since the 2000s, the Socialist Party of Italy has consistently retained a plurality of seats in the Chamber of Deputies to maintain control over the government. As such, political watchdog organizations have described Italy as a dominant-party system in part to the electoral and historical advantages of the Socialist Party of Italy. The party remains the preeminent left-leaning party in the country and has remained popular among older generations of Italians and those in Southern Italy.

The opposition has been divided between numerous political parties across the spectrum including liberal and conservative parties, as well as regionalist parties which have made it difficult to disrupt the relative dominance of the Socialist Party. At the region-level, oppositional political parties have fared better where regional legislatures are more competitive and balanced. The Great North Party, the Italian Fatherland Party, and the National Italian Alliance are major right-leaning parties which perform well in the subnational governments of Northern Italy. The main liberal and social democratic parties are the Italian Liberal Party, the Social Democratic Party of Italy, and the Progressive Party of Italy.

Foreign relations

Italy is a member of the League of Nations. It maintains an official policy of neutrality. It is a member of a number of other intergovernmental organizations including the Organization for Mutual Economic Assistance and Development and G25. During the Cold War, Italy was one of the leading Landonist states in Europe. Following the reforms, it continued to maintain close relations with the Landonist world and post-Landonist states, especially with the United Commonwealth, which share political and cultural ties. It is militarily non-aligned and is non-interventionist. In the 21st century, it has improved relations with the CAS and its member states, especially the Kingdom of Sierra.

Throughout much of modern history, Italy has been regarded as a great power and major influence in international relations. It continues to play an active role at the international stage by working on global issues including organized crime, drugs, trafficking, terrorism, piracy, and internet fraud.

Military

The Italian Armed Forces comprises four military branches: the Italian Army, the Italian Navy, the Italian Air Force, and the Carabinieri. The four branches are administered by the civilian Ministry of Defence and the operational military head of the Italian Armed Forces is the Chief of the Defence Staff. Officially, Italy maintains a policy of neutrality although it participates in the sale and purchase of military arms with a number of other countries. The Constitution of Italy has dedicated sections detailing the purpose, functions, and organization of the Italian Armed Forces. The President is the commander-in-chief of the Italian Armed Forces and the Italian Parliament has the power to declare war, issue a military draft, and to finance the military. In addition to the national military, each region has its own regional militia which consists of servicemembers and reservists who may be deployed during times of emergency or disaster.

Italy retains a system of conscription: all Italian men between the ages of 18 and 30 must serve at least 6 months of mandatory military service. Under Italian law, mandatory military service includes both combatant and non-combatant roles. Military service for women is completely voluntary.

The Italian Army is the ground forces of Italy and traces its origins to the Royal Italian Army. The contemporary Italian Army is mostly involved in peacekeeping missions. The Italian Army also includes the Carabinieri, its most senior mechanized division which has been elevated to de facto military branch status. The Carabinieri functions effectively as the state police or gendarmerie forces and is responsible for general law enforcement.

The Italian Navy is a blue-water navy with one of Europe's largest fleet of vessels. It operates more than 150 vessels in active service, including minor auxiliary vessels. The Italian Navy also includes the Italian Coast Guard which patrols Italy's shorelines, internal waters, and islands.

The Italian Air Force operates a fleet of over 200 combat jets and was once a division of the Italian Army. Its responsibilities are to protect and patrol Italian's aerospace. It is also responsible for Italy's missile and anti-aircraft infrastructure.

The Guardia di Finanza (Financial Guard) is a militarized law enforcement agency of the Ministry of Finance that uses military-grade equipment and ranks system similar to the Italian Armed Forces but is not officially considered a part of the state military. Its responsibilities mainly involve the policing of Italy's drug trafficking and financial laws.

Administrative divisions

Under the 1995 Constitution, Italy is a federation composed of 19 constituent regions and one federal district. Each region is a federated unit of the Italian state and is further divided into provinces and municipalities. Each region has its own constitutions, legislatures, laws, and courts. Compared to other federations, Italy's regions have relatively less autonomy, as the Italian federal government retains broader, exclusive powers on reserve matters ranging from criminal and civil laws to national defense and trade.

Provinces are the intermediate level between regions and municipalities. The primary functions of municipalities are to administer and provide local services such as fire services, waste management, and public utilities, oversee zoning, regulate local transportation, administer voter registration, and keep vital records.

Municipalities, also known as communes or comuni (singular form: comune), represent the lowest level of government, and share overlapping responsibilities with provincial governments on providing public services and works.

| Flag | Coat of arms | Region | Capital | Area (km2) | Area (sq mi) | Population (2020) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Abruzzo | L'Aquila | 10,763 | 4,156 | 1,542,287 | |

|

Aosta Valley | Aosta | 3,263 | 1,260 | 140,342 | |

|

Apulia | Bari | 19,358 | 7,474 | 4,352,016 | |

|

Basilicata | Potenza | 9,995 | 3,859 | 571,633 | |

|

Calabria | Catanzaro | 15,080 | 5,822 | 2,002,710 | |

|

Campania | Naples | 13,590 | 5,247 | 6,151,773 | |

|

Emilia-Romagna | Bologna | 22,446 | 8,666 | 4,500,492 | |

|

Friuli-Venezia Giulia | Trieste | 7,858 | 3,034 | 1,203,474 | |

|

Lazio | Latina | 5,370 | 2,073 | 1,522,048 | |

|

Liguria | Genoa | 5,422 | 2,093 | 1,495,329 | |

|

Lombardy | Milan | 23,844 | 9,206 | 9,966,992 | |

|

Marche | Ancona | 9,366 | 3,616 | 1,501,406 | |

|

Molise | Campobasso | 4,438 | 1,714 | 296,547 | |

|

Piedmont | Turin | 25,402 | 9,808 | 4,269,714 | |

|

Rome Federal District | Rome | 5,363 | 2,071 | 4,353,738 | |

|

Sicily | Palermo | 25,711 | 9,927 | 4,969,147 | |

|

Tuscany | Florence | 22,985 | 8,875 | 3,722,729 | |

|

Umbria | Perugia | 8,456 | 3,265 | 865,013 | |

|

Veneto | Venice | 18,345 | 7,083 | 4,852,453 |

Economy

| Economic indicators (measured by KS$) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Nominal GDP | $2.443 trillion (Q3 2018) | |

| Real GDP growth | 3.5% (Q2 2022) | |

| CPI inflation | 1.9% (June 2022) | |

| Employment-to-population ratio | 43.7% (June 2022) | |

| Unemployment | 5.9% (June 2022) | |

| Labor force participation rate | 64.2% (June 2022) | |

| Total public debt | $3.30 trillion (124.5% of GDP) (June 2022) | |

| Avg. household net worth | $333,291 (Q3 2020) | |

Italy has a major advanced economy that is open and a mixed economy. It is one of the most industrialised countries in the world and the third-largest economy in Europe after Germany and the United Kingdom. More than three-fourths of the country's workforce are employed in the tertiary services sector. It also has a large manufacturing sector as the world's fourth-largest manufacturing country. Italy is a member of the European Community, G20, and the OMEAD. Its largest trading partners are the European Community, the United Commonwealth, China, and the Kingdom of Sierra. Italy is also a major exporter and is a global leader in high-end luxury products such as clothing, jewelry, and automobiles.

After the Italian Revolution, Italy's economy transformed from an agrarian-based economy into one of the world's most industrialised nations. Under the Italian Socialist Republic, Italy operated under a centrally planned economy that was run by a large government bureaucracy. The state held a monopoly on virtually every sector through state-owned corporations although a number of small and medium-sized private firms were allowed under state supervision. Following the Lily Revolution, Italy's economy liberalised and key industries were denationalised, allowing for more private entities to start their own businesses. Due to its history and strong labor movement, Italy's economy has only a number of global multinational corporations. The majority of Italian companies are small and medium-sized enterprises, characteristic of the firms permitted during the Socialist Italian period, and centred around a number of industrial districts. The modern Italian economy is robust and advanced as one of the leading nations in innovation and creativity. However, there is a noticeable disparity between the North and the South. The North, on average, has higher standards of living and level of affluence, compared to the South. The GDP per capita for some Northern Italian regions exceeds that of the European average while some Southern Italian regions fall below the European baseline.

Agriculture

Italy's agriculture sector has been in existence for over five millennia. Although Italy is no longer a predominantly agricultural-based economy, its agriculture sector remains a significant contributor to the Italian economy. The northern part of Italy specialises in crops such as corn, rice, sugar beets, soybeans, meat, dairy, and fruit. The southern part of Italy specialises in wheat and citrus.

Italy is the world's top producer of wine and one of the leading producers in olive oil, apples, grapes, oranges, lemons, pears, apricots, hazlenuts, peaches, cherries, plums, strawberries, artichokes, and tomatoes. Italian viticulture is highly regional and includes famous wines such as Tuscan Chianti, Piedmontese Barolo, Barbaresco, Barbera d'Asti, Brunello di Montalcino, Frascati, and Prosecco. Italy is also renowned for its variety of specialized cheeses such as Parmigiano Reggiano (parmesan) and mozzarella di bufala (buffalo mozzarella).

Infrastructure

Italy was the world's first country to build and utilize motorways, known as autostrade, which are controlled-access highways designed for high-speed vehicles only. The country's road network is extensive and consists of over 450,000 km of roads. The Italian road system comprises national motorways, regional motorways, local streets, and toll roads. Italy also has a robust rail network with dedicated high-speed rail lines that connect passengers between Italy's major cities including Naples and Milan. Most railways are operated by the Italian government although there are also a number of private freight and passenger railways.

Italy is serviced by an expansive network of airports totaling more than 130. The busiest and largest airports in Italy are Malpensa International Airport in Milan and Leonardo da Vinci International Airport in Rome. The flag carrier airline is Italian Airlines whose primary hub is the Leonardo da Vinci International Airport.

Energy

Science and technology

Tourism

Demographics

Languages

Religion

Immigration

Culture

Architecutre

Visual art

Literature

Philosophy

Theatre

Cinema

Fashion

Sports

Cuisine

Public holidays and festivals

Public holidays in Italy are a combination of secular, religious, and regional observances. All public institutions and bodies including schools, as well as banks and other financial institutions are closed during public holidays. The most important days of the Italian calendar year are Easter, Republic Day, and Christmas.

In addition to the national holidays, each city or town celebrates their own public holidays in association with their local patronal saint. Generally speaking, whenever a holiday falls on a Tuesday or a Thursday, a ponte (bridge) is commenced to allow there to be a long weekend.

| Date | English Name | Local Name | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 January | New Year's Day | Capodanno | |

| 6 January | Epiphany | Epifania | |

| Sunday after the first full moon following the spring equinox | Easter Sunday | Pasqua | |

| Monday after Easter | Easter Monday | Lunedì dell'Angelo, Lunedì in Albis or more commonly Pasquetta | |

| 1 May | Labour Day | Festa del Lavoro (or Festa dei Lavoratori) | |

| 2 June | Republic Day | Festa della Repubblica | Birth of the Republic, 1946 |

| 15 August | Assumption Day | Assunzione (Ferragosto) | |

| 1 November | All Saints' Day | Tutti i santi (or Ognissanti) | |

| 8 December | Immaculate Conception | Immacolata Concezione (or just Immacolata) | |

| 25 December | Christmas Day | Natale | |

| 26 December | Saint Stephen's Day | Santo Stefano |

In addition to the public holidays, there is a wide variety of regional festivals and celebrations throughout Italy. The Carnival in Venice, Viareggio, Satriano di Lucania are world renowned festivities.

Education

Italian education ranks among the highest in the world. Education is compulsory between the ages of five to eighteen. Education is a protected, enumerated right in the Constitution of Italy and is overseen and administered by the Ministry of Education. Public education is available to all children for free, regardless of citizenship, and is divided into five stages: kindergarten (scuola dell'infanzia), primary school (scuola primaria or scuola elementare), lower secondary school (scuola secondaria di primo grado or scuola media inferiore), upper secondary school (scuola secondaria di secondo grado or scuola media superiore) and university (università). Higher education is also free and consists of public universities, private universities, superior graduate schools, and vocational schools. Several higher educational institutions are considered highly prestigious and selective, including the University of Bologna (the world's oldest university in continuous operation), the University of Padua, the Sapienza University of Rome, the University of Milan, and the University of Pisa.

Primary and secondary education is overwhelmingly public with the majority of private schools being parochial or sectarian in nature. All public primary and secondary schools are run by the Ministry of Education which implements the curricula, standards, and policies set by the government. All secondary education students must take academic evaluation tests and national exams to certify satisfactory competence prior to graduating and transition to higher education.

Health

Italy has one of the world's highest life expectancy. As of 2022, the life expectancy for an Italian male is 80 years old while the life expectancy for an Italian female is 85 years old. Compared to other Western nations, Italians are less likely to experience adult obesity (below 10% of the average). The longer life expectancy and lower incidences of diseases and disorders associated with overeating has been attributed to the health benefits of the Mediterranean diet. Smoking rates are much lower in Italy in comparison to the rest of Western Europe, in part due to rigorous laws against smoking and drug use that were imposed during Landonist Italy.

The Italian state also runs one of the most advanced public healthcare systems. Post-communist Italy has retained the universal healthcare system introduced in Landonist Italy, although the liberalized healthcare system has been supplemented by private insurance and healthcare providers. The dual-system healthcare system is financed through mandatory health insurance enrollment. Italy spends more than 15% of its GDP on healthcare and the public healthcare system is administered by the National Health Service.

See also

| This page uses material from the Wikipedia page Italy, which is released under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License (view authors). |

| This page uses material from the Wikipedia page History of Italy, which is released under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License (view authors). |

- C-class articles

- Altverse II

- Italy

- 1861 establishments in Europe

- Countries in Africa

- Countries in Europe

- Federal republics

- Italian-speaking countries and territories

- Member states of the European Community

- Socialist states

- Southern European countries

- States and territories established in 1861

- Transcontinental countries