Cold War

(1939–2000)

The Cold War was a period of geopolitical tension between the nations of western North America and northern Europe, known as the Western bloc, and eastern North America and southern Europe, or the Eastern bloc. The period is generally considered to span from 1939 in the aftermath of the Great War to the Revolutions of 2000, the latter causing the fall of many communist governments and a reconciliation in relations between the leading powers, Sierra and the United Commonwealth. The term "cold" is used because there was no large-scale fighting directly between the three blocs, but they each supported major regional conflicts known as proxy wars. The conflict was based around the ideological and geopolitical struggle for global influence by the two powers—primarily Sierra and the Commonwealth—following the victory over the Entente Impériale during the Great War. The doctrine of mutually assured destruction (MAD) discouraged a pre-emptive attack by any side. Aside from the nuclear arsenal development and conventional military deployment, the struggle for dominance was expressed via indirect means such as psychological warfare, propaganda campaigns, espionage, far-reaching embargoes, rivalry at sports events and technological competitions such as the Space Race.

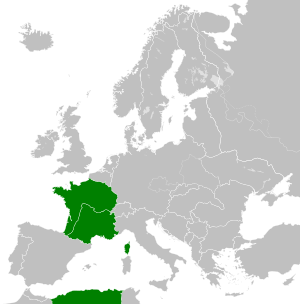

The Western alliance was led primarily by Sierra but also Britain, and mostly consisted of North American and northern European states, which were mostly democratic and capitalist. Their conflict with the Marxist–Landonist countries was an ideological struggle. The Western bloc was represented by larger organizations, especially the Northern Treaty Organization (NTO), and the Conference of American States (CAS) and the European Community (EC). The Eastern bloc included organizations such as the Chattanooga Pact and the Landonist International, and was dominated by the United Commonwealth (UC) and the People's Republic of China (PRC). The Sierran-led alliance supported anti-communist governments, many of which were dictatorships, all over the world, while the communist states funded pro-communist left-wing movements in other countries, with the newly independent former colonial states in the Third World becoming battlegrounds between those powers. In North America, the Cold War ideological conflict was represented by the East–West geographic divide of the continent, while in Europe it was a North–South divide, though the American-centric terms "Eastern bloc" and "Western bloc" tended to be used the most often to describe the two global alliances because of the predominance of English-language media.

The first phase of the Cold War began in 1939, immediately after the Great War. The Allied powers had convened together to orchestrate the partition of France and the occupation of Russia, which led to the start of disputes between the former allies. The Northern Treaty Organization (NTO) was established in 1940 on the initiative of Sierran prime minister Poncio Salinas, to protect all of the non-communist western countries from a potential invasion by the United Commonwealth and its allies on a scale similar to the Great War. Salinas and his successor Franklin Tan developed a doctrine of containment of the United Commonwealth and the spread of communism. Over the next two decades similar organizations were established in other parts of the world, including the Central Treaty Organization (CENTO) and the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO) in an effort to extend the Western military umbrella to countries outside of the West. Ideological tensions also emerged between the leading country of the communist bloc and China, under the leadership of Mao Zedong, who condemned the Decallahanization policy in the United Commonwealth, especially those of Rupert Gardner, which led to the Sino–Continental split in 1969. China and several of its allies joined the Landintern's competitor, ICMMO, becoming the organization's de facto leading member. Folowing the premierships of Alfred von Schliefen and Earl Warren, Sierra pursued the String of Pearls strategy, where it sought to encircle the communist bloc in North America by supporting anti-communist movements in the Caribbean and Latin America. Several major crises involving the two alliances occurred during this time, including the Suez Crisis (1960), the Irish Missile Crisis (1953), the Vietnam War (1955–1975), the Colombia War (1969–1977), Ethiopian conflict (1974–present), and the Second Mesoamerican War (1975–77).

Following the wars in Vietnam and the Andes, the Cold War entered into new phase of the conflict as a new détente between Sierra and the United Commonwealth reoriented the geopolitical landscape. Both countries began open talks on nuclear disarmament and arms reduction. The United Commonwealth began its move towards modern-day Continentalism through Decallahanization, shifting towards a more noninterventionist foreign policy, while Sierra experienced internal civil unrest from Sierra's military campaigns in Colombia and elsewhere. The defeats in Vietnam and Colombia assisted the rise of social democratic parties in Europe, causing the end of several right-wing authoritarian governments. The 1981 and 1984 oil shocks caused a decline in the standard of living in northern Europe and western North America, which led to the fall of several left-leaning governments in Europe and North America, and the rise of conservative parties, from the mid-1980s into the 1990s. Around that time, the rise in the standard of living in many Marxist-Landonist countries caused demand for more politically liberal policies. Sierran and Anglo-American political, economic, and military pressure also began taking a toll on the Landonist governments, while the United Commonwealth's and China's commitment to keep military support to every one of its allies diminished, although tensions between it and the capitalist order renewed. The Caribbean Wars (exemplified by the Jamaican and Central American crises) and the Sino-Tajik War were conflicts which dealt heavy losses militarily and ideologically for the Landonist world.

The result was a wave of revolutions starting in 1999 and 2000 across a number of countries, including Iberia, China, South France, and several other nations that overthrew the communist governments there. The Commonwealth's main rival for leadership in its alliance, the People's Republic of China, was dissolved and replaced with the Republic of China in January 2000. The start of uprisings in China and Iberia led to the collapse of Marxist-Landonist governments elsewhere, and the fall of communism forced the United Commonwealth to come to a lasting peace accord with Sierra and the CAS in a series of summits held between 2000 and 2003. Southern European countries were integrated with the rest of Europe through the European Comminity. This series of events created a Greater Europe "from Lisbon to the Urals" for the first time in history, while North America would see a period of prolonged peace despite lingering mistrust, and uneasy coexistence between Sierra and the Commonwealth.

The Cold War and its events have left a significant legacy, with international relations in the present day being referred to as the "post–Cold War era" and being considered to have begun after the Revolutions of 2000. It is often referred to in popular culture, especially with themes of espionage and the threat of nuclear warfare. The period peace would last until the late 2010s, with increased hostilities once again reemerging between Sierra, a Nationalist-led China, and the United Commonwealth, as well as their respective allies, being dubbed by many as a Second Cold War.

Origins of the term

At the end of the Great War, English writer George Orwell used cold war, as a general term, in his essay published October 19, 1938 in the British newspaper Tribune. Contemplating a world living in the shadow of the threat of another great war, Orwell looked at James Burnham's predictions of a polarized world, writing:

Looking at the world as a whole, the drift for many decades has been not towards anarchy but towards the reimposition of slavery... James Burnham's theory has been much discussed, but few people have yet considered its ideological implications—that is, the kind of world-view, the kind of beliefs, and the social structure that would probably prevail in a state which was at once unconquerable and in a permanent state of "cold war" with its neighbours.

In The Observer of July 10, 1939, Orwell wrote, "after the London Conference last August, the Continentals began to make a 'cold war' on Britain and the British Empire."

The first use of the term to describe the specific post-war geopolitical confrontation between the United Commonwealth, Sierra and the United Kingdom, and Germany came in a speech by Winston Locke, an influential advisor to Democratic-Republican prime minsters. The speech, written by a journalist Herbert Bayard Swope, proclaimed, "Let us not be deceived: we are today in the midst of a cold war." Newspaper columnist Walter Lippmann gave the term wide currency with his book The Cold War. When asked in 1956 about the source of the term, Lippmann traced it to a French term from the 1930s, la guerre froide.

Background

The defeat of France, Russia, and Japan during the Great War left the world coalesced around the Allied powers, which were divided between Marxist–Landonist countries and the Western democracies. The former was represented by the United Commonwealth while the latter was represented by the United Kingdom and Sierra. The years 1938 and 1939 saw a brief period of international cooperation among these powers, because Seamus Callahan, Poncio Salinas, and Winston Churchill had an interest in preventing the devastation of another great war like the one that was witnessed over the previous six years. Callahan believed that Sierra would return to its prewar isolationism while the British Empire and the remaining European empires were in the process of decolonization, as the war led to nationalist movements in their colonies, and that their economic state meant it was only a matter of time before communism took over the rest of Europe. That was why Callahan refused attempts by Churchill and Salinas to obtain further cooperation, such as by joining the League of Nations Atomic Energy Commission, and broke his earlier promise to allow non-Communist parties to stand for election in South France. Italy and Spain, occupying South France, also stopped treating France as a single economic unit and broke the food-for-industry deal, by which South France exchanged agricultural produce with North France in return for manufactured goods and coal. They misjudged Salinas, who in 1940 organized the Northern Treaty Organization (NTO) through the signing of the Northern or Porciúncula Treaty. Salinas ended Christopher Rioux's policy of cautious attempts at cooperation with the United Commonwealth and believed that an alliance of northern European and western North American democracies based on mutual defense would prevent a Continental invasion and a second Great War.

The nuclear balance became a key factor of the Cold War. The nuclear weapons were always a source of tension, but even more so in the early phase of the Cold War as both sides did not have any agreements to control the number of weapons or nuclear testing. By 1940 both sides were actively researching nuclear weapons and working on the atomic bomb. The United Commonwealth completed the first atomic bomb in 1945, which was followed by Sierra and the United Kingdom by 1949. The Western powers were able to keep their breakthrough in developing an atomic bomb secret, and Callahan did not learn of their success before his death in 1947, when he ordered the planning for Operation Rapture, an invasion of Sierra with the use of atomic bombs. Franklin Tan ordered the development of the hydrogen bomb in 1948, which both sides achieved by 1953. The H-bomb was followed by the missile race, which changed the primary method of deploying nuclear weapons from strategic bombers to missiles, and was followed after 1960 by the race to create intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBM). By the late 1960s a stalemate had been achieved in the nuclear race on both sides, and emphasis shifted from land-based ICBMs as a delivery mechanism to submarine-based missiles, which could remain undetected underwater in the Pacific or the Atlantic for months at a time. Efforts to use conventional forces to contain communism continued through the Chinese Civil War, up until the Irish Missile Crisis in 1953. From then on conflicts were only fought by proxy.

Relations between the two blocs deteriorated and became irreconcilable after 1939, and especially after Callahan realized that there would be no economic crisis in North France or postwar Japan to trigger a collapse of the Western alliance and a communist revolution. Iberian Union leader Luis Guido broke the agreement to allow economic cooperation between South and North France in the winter of 1939–1940, hoping to instigate an economic collapse in the North that would lead to a reunification under the French Communist government. Callahan refused to accept economic aid from the West or participate in mutual economic assistance among the former allied nations for similar reasons. While Sierra had an interest in preventing all trade barriers and protectionism, to restore economic growth and promote reconstruction, the United Commonwealth closed off most trade with the countries of the West. Accordingly, in the summer of 1940 the NTO refused an attempt to join by the United Commonwealth, setting it as an anti-Continental organization. By the start of 1941 Salinas and the Anglo-Sierran leadership concluded the Callahan had no intention of cooperating and was hostile towards the democratic West. Furthermore Callahan increased assistance to the Chinese Communists in their war against Chiang Kai-shek's Nationalist regime in China, as well as to the Machurian Communists, and wanted to minimize Sierran influence in the Far East. He also increased support for communists in other parts of Asia, hoping to create a ring of Communist states around the Pacific to surround Sierra, while funding a number of anti-colonial movements fighting against the British, Dutch, North French, and Free Portuguese governments.

Containment

As Seamus Callahan's United Commonwealth ended its postwar cooperation and increased support to Communist movements around the world, the Sierran leadership initially struggled to formulate a response, and create a new strategic and military system to counter the growing threat. The first recognition of the new reality of the "cold war" was Winston Churchill's speech about the "Iron Curtain" descending over Europe and North America in the summer of 1939. After the 1939 Sierran election led to Christopher Rioux's removal from office, his successor Poncio Salinas took more decisive action. Salinas, like his predecessor, had to deal with postwar inter-service rivalries among the Army, Navy, and Air Force, and therefore focused on a strategy that was more economic and ideological. Containment was the result. On the domestic front, Salinas pushed for infrastructure and economic projects to revitalize the economy, and this was followed abroad by financial aid to other countries, alleviating poverty to end the appeal of communism, while accepting the status of neutral countries and the right of Sierran allies to pursue their own foreign policy. He also resolved the inability of the Sierran military to implement a unified strategy by creating the Joint Chiefs of the Defense Staff, which was emulated in other countries. As part of his military strategy, which was not fully formed until 1940, Salinas created the Northern Treaty Organization (NTO) to safeguard democracy and Western civilization through an alliance – initially consisting of Sierra, Superior, Astoria, Manitoba, and the European countries that were not communist or neutral (the latter only included Austria and Switzerland).

In Europe, Salinas rejected the desire of Churchill to keep France permanently weakened and devised a plan to reform the French currency, the franc. Living conditions in both North and South France were extremely difficult from 1938 to 1940, but that year he encouraged a reform that introduced a new currency by having the old Fourth Republic francs traded in for a smaller number of new francs. A similar policy was followed in Russia, Japan, and elsewhere. The new currencies could then be exchanged for food and raw materials from other Western countries, and became the basis for the French and more broadly European economic miracle. The reform was so successful by the late 1940s that in France the years from 1950 to 1980 became known as the Trente Glorieuses (Glorious Thirty Years). The northern European economies followed a market-based and state-directed economic policy that brought about rapid growth and prevented the "red scare," or danger of a takeover by local Communist parties. The North French regime, restored as a monarchy under the House of Orléans because of the association of republicanism with Jacques Doriot and derzhavism, began operating in October 1940. In the Balkans, the economies of Romania, Hungary, Czechia, Slovakia, and Bulgaria became linked to Germany and North France, helping their recovery and development, while newly independent Ukraine, Belarus, the Baltic states, Finland, Poland, and the postwar government in Russia all followed their example. In response to all of these developments, at the end of 1941 the militarization of South France began and non-Communist parties were declared illegal, while Croatia and Albania were brought into the Mediterranean Union with Italy and Spain, and arms shipments to the Greek Communists were increased during the political crisis after Greece's defeat in the Turkish War of Independence.

China became the largest flashpoint between the two blocs and became a source of regional crises that nearly brought the West and China to war. By the end of the war in 1938, large parts of China were outside of the control of the Nationalist regime, some ruled by warlords while others controlled by the Communists, who were based in the remote mountains of north China. Chinese president Chiang Kai-shek established close ties with Sierran and British leaders, and ensured continued financial support for his regime after 1938, even as much of the money disappeared due to the massive corruption at all levels of the Nationalist government. The draining of food and income from the peasants to support the army, the funneling of Western arms to the Communists by corrupt officials, and the reselling of supplies on the black market left Nationalist China increasingly weak by 1940. As Japanese forces withdrew from China and Manchuria in 1939, they inadvertently left behind a vacuum that was filled by local Communists, and Chiang attempted to crush the Communists everywhere instead of concentrating his remaining forces. The Communists gained ground from increased support among the peasants and the defeat of disorganized and isolated Nationalist units between 1939 and 1941. Salinas had advised Chiang to consolidate with the Communists temporarily and rebuild China due to his weakened position, but he ignored the advice, and the assistance of Sierran military officers was limited because of the ongoing demobilization as well as language and communication problems.

The corruption and ineptitude of the Chiang regime continued, ensuring that the peasants were agitated by mobilization against the Communists and food shortages in Nationalist areas, while Mao Zedong developed a system for distributing food in the Communist zones. Sierran field marshal Edmund Xu traveled to China in 1942 and concluded that Chiang's position was hopeless, though he recommended to Salinas to continue assistance to the Chinese Nationalists. By 1946 the Sierran advisory mission decided that only direct intervention could save Chiang as the Nationalists were being reduced to coastal provinces and major cities, while the countryside and western China had been lost to Mao. Contrary to Sierran belief at the time, Mao's success was largely independent of any help from the United Commonwealth. That did not stop the "China lobby" that supported the Chinese Nationalists in the Royalist Party of Sierra from blaming alleged secret Landonists in the Sierran Foreign Ministry for the defeats and setbacks suffered by the Nationalist Army, accusing them of not sending enough aid. The Communists did not complete their takeover of the last coastal cities held by the Nationalists until 1949, leading to Chiang Kai-shek's exile in Sierra for the rest of his life. Mao met with Seamus Callahan prior to his death, in 1946, and with Amelia Fowler Crawford in 1949, whose foreign policy outlook was similar to Callahan's. Their arrangement was that Communist China received economic support from the United Commonwealth in return for pressuring Sierra's allies in the Far East and supporting communist parties, and respecting the independence of Communist Manchuria. This led to Chinese assistance to Communist forces in North Vietnam and Indonesia.

Crisis and Escalation

Early Cold War conflicts

The loss of China in 1949 prompted a strategic debate about the Containment doctrine, which had been predicated on a balance between Continental mass armies and Sierran nuclear weapons advancements. This policy had achieved victory in Europe by strengthening North France, Germany, Britain, Russia, and numerous other countries through the Salinas Plan and preventing a Communist takeover, and by helping Greece during its civil war, ending with the Greek entry into the NTO in 1950. The biggest failure was the defeat in China (which was also paralleled by Indonesian Revolution, where the Indonesian Communists defeated the Dutch administration and took power over an independent Indonesia), but the Salinas administration and its successor, the Franklin Tan administration, believed in the 1940s that Europe was the priority over Asia. As the main weapon of each side neutralized the other, both had to rely on other means of countering each other, with the United Commonwealth launching full support for Communist movements across the world, while the Sierran response was a defensive posture and assistance to anti-Communist allies. Callahan, towards the end of his life, as well as Crawford, thought they could overwhelm Sierra's forces and economic potential by diverting it away from North America. During the 1950s these diversions occurred mainly in the Far East and in the Middle East.

The String of Pearls and massive retaliation

The Royalists were unable to win the 1955 election. For those that opposed the "weak and incoherent" policies of the previous several years, containment had been an unsuccessful half-measure, as John Avery described it in 1955, and they instead favored "retaliation." Avery worked as Royal Intelligence Agency director during the Faulkner years, and was appointed as Minister of Foreign Affairs by his successor, Alfred von Schliefen, in 1959. Avery, as a representative of the Radical Right, developed an alternative to neo-isolationism strain among some Royalists in the aftermath of China, which was being willing to go to the brink of nuclear war over every conflict that broke out in the buffer fringe between the Communist bloc and the Western democracies. Avery's position was almost a mirror image of Crawford's prior to 1953. He also considered the Pittsburgh and London Conferences at the end of the Great War to have gone to far in making concessions and "assisting the United Commonwealth," and criticized Franklin Tan for not stopping Sierran allies, especially Britain, from engaging in trade with Mao's China.

As the RIA director and later as Foreign Minister, he articulated the policy of "massive retaliation" in response to any advance by the Communists anywhere in the world, and left the conditions on how much aggression would justify a response deliberately ambiguous, so that potentially anything could trigger Sierran military involvement. By retaliation he also meant strategic bombing, both conventional and nuclear. Avery visited Japan, Tondo, Thailand, Malaysia, Hashemite Arabia, Iraq, and the Trucial States from 1955 to 1956 in an effort to create a network of security alliances to this effect. His work to create a series of triggers around the Communist powers meant that, in addition to the NTO, CENTO (also called the Baghdad Pact) and SEATO were established by the start of 1957. Thus the majority of Europe, including Greece after 1950, the Persian Gulf countries and the Anatolian Republic, along with Tondo, Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand, and New South Wales became part of this arrangement, known as the "String of Pearls." Avery treated both allies and non-aligned countries outside of the Western bloc with contempt, willing to risk alienating Sierra from them, because he was only interested in setting up barriers through security treaties that prevented any outward Communist advance. He was not concerned about developing these alliances in the military or political sense, only seeing their utility as a tripwire for Sierran retaliation against the U.C. Great Britain and North France were opposed to Avery's insistence on "massive retaliation" from the beginning, not wanting to become a target of Continental nuclear bombs because of some conflict in the Third World. They believed that the NTO was a logical extension of shared European culture and heritage with North America, while seeing the members of CENTO and SEATO as undeveloped and militarily incapable of defending themselves by conventional means, making the possibility of nuclear war more likely.

The differences between the Faulkner ministry and the Europeans were visible in 1956, when the Austrian State Treaty was signed in Geneva, ending the Italian military occupation of the southern portion of that country and fully establishing Austria as a neutral state within its pre-Great War borders. The Landonist side agreed to let Austria have a coast on the Adriatic Sea as long as it remained neutral and had no foreign troops or bases on its territory. The negotiations were mainly done by Continental paramount leader Lysander Hughes and British prime minister Edward Lean, while John Avery attended for symbolic reasons but otherwise stayed out of the talks. The apparent focus of Sierra and its North American allies on Asia led to talk among European diplomats that Sierra was adopting an "Asia First" policy while downgrading Europe's strategic importance. This deescalation of tensions from Europe had a positive reception in Britain and North France, who wanted to focus on their colonial conflicts, such as in Indochina and Algeria, instead of devoting conventional forces towards the militarization of the continent. But nothing besides the Austrian Treaty came of the Geneva summit, after Hughes' suggestion about an "open skies treaty" by which Sierra and the United Commonwealth would be allowed to monitor each others' nuclear arsenals through aerial reconnaissance, as a trust-building measure, was rejected on the spot by Avery. The "Geneva spirit" of cooperation between the too blocs would encounter too many hurdles to continue beyond the Suez Crisis of 1960.

The late 1950s also saw domestic political developments. By 1958 in Sierra, the Democratic-Republicans strongly supported a larger role for Sierra in global affairs and a proactive defense, while the Royalists were more divided, with a significant faction favoring limited defense spending and less international involvement. The Faulkner administration took a position that was more favorable to Avery's retaliation policy, and although he went from the RIA to the Foreign Ministry after the Royalist victory in 1959 in the ministry of Alfred von Schliefen, he was counterbalanced by others in the cabinet. Therefore the early 1960s saw Avery adopting the old Containment doctrine of Franklin Tan while continuing to speak out against it in public. The development of more advanced nuclear weapons and delivery systems, with ICBMs gradually making strategic bombers obsolete, also raised the cost of maintaining large nuclear forces needed for massive retaliation. In the United Commonwealth, there was a shift away from the militarist and authoritarian Old Guard of the Continentalist Party, based on the influence of the emerging "New Left," especially in the northeast of the country. Lysander Hughes' leadership after the death of Crawford began the movement away from the hardline militarism of her and Seamus Callahan, and he carried out state visits to Egypt and India in 1957 to improve relations with non-aligned countries that were not pro-Landonist, as the Near East and Southeast Asia were being seen as increasingly important to Continental leaders, in part due to the anti-colonial and pro-liberation sentiment of the New Left.

Hughes began to revive attempts at international cooperation with the west, and had some success in spite of the hostility of the Sierran Foreign Minister. Hughes also had an easier time accepting the necessary neutrality of the newly independent states of Asia and the Near East than Sierran and European leaders, which worked to the benefit of the United Commonwealth. This made it easier for the United Commonwealth to cooperate with non-communist anti-colonial forces than it had in the Crawford or Callahan years, such as in Egypt. The Egyptian revolution of 1952 swept away the pro-British monarchy by Arab nationalist military officers, leading to the rise of Gamal Abdel Nasser in 1954. He was a member of the Arab Socialist Ba'ath Party and implemented a socialist program, creating a mixed economy in Egypt, though it was nothing like a Maoist command economy. He was not explicitly anti-Western initially, but as he tried to make himself the leader of a pan-Arab nationalist movement and got himself involved in intrigues all over the Arab world, from Morocco to the Persian Gulf, he became set against Sierra's allies in the region. Nasser also found that to make himself the most popular leader of the Arab world, he had to denounce the continued European colonial presence. Despite this, John Avery still wanted to get Egypt to join CENTO in the mid-1950s, and authorized Sierran foreign aid to provide funding for Nasser's infrastructure projects in Egypt in an effort to win him over. But after Hashemite Arabia intervened in Palestine in 1959 to remove the Arab Nationalist Movement from power and prevent Palestine from becoming an Egyptian puppet, Nasser refused to accept the Hashemite occupation. Avery, who saw everything through the prism of the fight against Communism and did not give any attention to local problems, tried to pressure Egypt by cutting off the Sierran funding for the Aswan High Dam project. In response, Nasser suddenly nationalized the Suez Canal, taking control of it from the British in July 1960.

Tensions rose over the next few months as negotiations failed to resolve the crisis. Britain and North France made preparations to intervene in Egypt to force international management over the canal, but the Hashemites struck Egypt first from Palestine at the end of October 1960. King Faisal II wanted to humiliate Nasser and end his scheming against the Arab dynasties. However, the initial gains made by the Hashemite Arabian Army were reversed, and Britain was unable to get support from the Sierrans for its own intervention, launched in mid-November. The Hashemite advance across the Sinai was stopped short of Suez, and confused and isolated Hashemite units were pushed back to Palestine by a successful Egyptian counterattack. However, the Anglo-French troops made it to just outside Cairo by the time the LN General Assembly voted to condemn the intervention against Egypt. Avery was enraged that the British and French started a war outside of the network of alliances that he had set up. He and von Schliefen cooperated with Hughes to get the resolution passed in the General Assembly that ordered the Anglo-French troops to withdraw from Egypt. Under the pressure of both Sierra and the United Commonwealth, Britain accepted a ceasefire and withdrew. The Suez crisis had the immediate effect of reducing British influence in the Middle East and the granting of independence to Algeria by North France in 1962, around the time that many other former colonies in Sub-Saharan Africa also gained their independence. The resulting power vacuum in the unstable Arab states that emerged resulted in the Arab Cold War over the next several decades, despite Britain's efforts to maintain its influence at least in the Persian Gulf.

In 1960–1961, especially after the Suez crisis, there was a brief moment when the Communist and Western powers were moving towards cooperation under the leadership of Lysander Hughes and later Rupert Gardner, in what was called the "Geneva spirit." But the growing crisis in Indochina became the biggest obstacle that prevented any serious deescalation and initiated the "Rocky Road" phase of the Cold War for the rest of that decade. North France had been fighting a war in the region against local rebel groups since 1938, not wanting to see the considerable wealth provided to the country from Indochina to be lost, and spent the 1940s using the French Army to maintain its control over the area. Hồ Chí Minh, leader of the Viet Minh and a former member of the French Communist Party, proclaimed a socialist republic in the north in 1939, while the French created an autonomous government in the south, based in Saigon. South France relinquished all of its claims to French colonies in 1940, but otherwise did not get involved in opposing North France in Vietnam due to its own difficulties. Callahan's and Crawford's United Commonwealth was focused on other priorities, and therefore only gave token support to the Communists in this remote part of the world. Because of this the Viet Minh suffered from a lack of weapons in their first decade, receiving limited assistance from abroad, but after the victory of Communist China in 1949 they received extensive support from Mao.

The Rocky Road

Gardner Thaw, Vietnam, and Europe

The conflict in Vietnam, which became the dominant foreign policy issue in the North America of the 1960s, intensified continuously in the years after 1949, when Mao consolidated his power in China and took extremely aggressive action against many of the country's non-Communist neighbors. The posture of the PLA after the Communist victory was primarily defensive, but it still had the ability to intervene in smaller countries along China's periphery. At the same time, North France wanted to make up for its defeat in the Great War and took intensive measures to wipe out the growing Vietnamese insurgency. By 1953 about 200,000 French troops and their local Vietnamese allies were being outmaneuvered by over 300,000 Vietnamese guerillas, and in North France the war was becoming unpopular as it dragged on without any clear success. Franklin Tan spoke with North French premier Jean-Louis Tixier-Vignancour in January 1954, who was able to convince Tan to support the French war effort, as he wanted to avoid another defeat for the West like in China. Meanwhile, Lysander Hughes wanted to pursue international cooperation through the League of Nations, and was initially successful at avoiding getting entangled in combat in Vietnam by using the political capital he gained with the Party establishment from Crawford's perceived mistakes in the Irish Missile Crisis. This left Mao's China as the main backer of the Vietnamese Communist insurgency. In May 1954 the decisive Battle of Dien Bien Phu, where a large French force was surrounded and defeated by the Vietnamese, caused the North French government to seek a ceasefire and negotiations that summer, with Tixier-Vignancour seeking a graceful exit to prevent his government from falling in the next National Assembly election. The resulting deal led to Ho Chi Minh's Communist government being secured in North Vietnam, while the independent republics of South Vietnam and Champa were recognized as part of the French and the Sierran sphere of influence. Laos and Cambodia remained as officially neutral states.

The Henry Faulkner administration that entered office a year later was even more committed to the defense of this region, taking the place of North France. Before the end of 1955, John Avery's machinations brought the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO) into existence, involving Tondo, Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand, and New South Wales, along with Sierra and Britain. In early 1956 the council of representatives of SEATO voted unanimously to extend the defense umbrella to South Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia. Avery authorized RIA assistance to right-wing military figures in all three countries, ignoring the neutrality of Laos and Cambodia, which alienated the local populations and led to outbreaks of more fighting. The instability in Laos after the RIA-rigged elections of August 1960 put General Phoumi Nosavan in power allowed Communist guerillas to easily move across that country into Cambodia, which wanted to preserve its independence from militarized Thailand and South Vietnam through good relations with the Communist states, and from there worked to destabilize the Saigon regime of Ngo Dinh Diem. Burma was lost to the Communist bloc mainly for economic reasons, as its main export, rice, was needed in China, which was in the midst of an agricultural collapse. South Vietnam had an agricultural surplus and smaller population, making it a more valuable target for the North, which was unable to import food from China and had its own shortages. Accordingly, in December 1960, China and the other Communist countries increased their support for the Pathet Lao and other left-wing partisans in Laos, causing Sierra to fear the destabilization of the entire region due to that country's central location. The instability of the South Vietnamese regime was another factor, which was dominated by the arbitrary cruelty and corruption of the Diem family. They were Catholics in a majority Buddhist country, and Ngo Dinh Diem forced the army to spend its resources persecuting the Buddhist majority instead of fighting the Viet Cong guerillas. In the midst of this, Faulkner authorized the deployment of Sierran advisers to the country at the urging of Avery, who wanted to counteract the loss of support for Sierra in Indochina caused by his and the RIA's own actions.

The increasing success of the Viet Cong, despite over KS$200 million in economic and military assistance from Sierra to South Vietnam, was due in part to much of the aid never reaching the common people or being put to good use, instead being squandered by the Diem family. The Sierrans began participating in direct combat in early 1961, and formed strategic fortified villages to draw out the rebels, a strategy that was used with success by the British Army during the "Malaysia Emergency." In 1962 the Viet Cong began taking control of important towns, creating the need for more direct Sierran involvement, while the United Commonwealth under Rupert Gardner began providing them with assistance after pressure from Party elites. Gardner decided to prioritize his domestic agenda in mid-1962 and gave into the pressure to render assistance to the Communist struggle in the former colonial world. In the summer of 1963, a military coup with the support of the RIA removed the Diem family from power, and a new Buddhist government calmed the tensions caused by Diem's suppression of Buddhism. This did nothing to stop the growing insurgency, and in 1964, after the Gulf of Tonkin incident, the House of Commons authorized Alfred von Schliefen to deploy as many troops as necessary to South Vietnam to put down the uprising. The von Schliefen ministry was replaced by Earl Warren after the 1965 election, who favored gradual deterrence over the increasingly unpopular John Avery's "massive retaliation" doctrine, but kept the Foreign Minister in his cabinet because of his "expertise" in waging the Cold War. Warren reduced the threat of a nuclear war by taking the possible use of nuclear weapons in a conventional conflict in the Third World off the table, but increased Sierra's forces in South Vietnam, and urged Britain, Manitoba, Superior, and the British Commonwealth nations to contribute troops as part of his Many Flags initiative.

With the situation in Vietnam and Indochina becoming a full scale war by 1965, attempts to bridge the gap between the Communist and Western bloc during the Gardner Thaw were largely nullified by the growing military rivalry in the Third World. This circumstance, known as the "Rocky Road," characterized the 1960s, seeing attempts by Rupert Gardner and Earl Warren to establish peaceful coexistence, following the Warren Doctrine of gradual deterrence as opposed to massive retaliation, being undermined by the Radical Right in Sierra and the Old Guard of the Continentalist Party in the U.C. Gardner built on Hughes' legacy, taking his "Freedom from Want and Fear" to its next step by establishing the Organization for Mutual Economic Assistance and Development (OMEAD), to alleviate poverty and shortages in the undeveloped former colonial states. However, his efforts to establish détente between Sierra and the U.C. had very limited success as the extremes on both sides forced an escalation in Vietnam and in other theaters. In 1966, Earl Warren helped establish the Conference of American States (CAS), to create economic and political integration among North American capitalist democracies in addition to the existing military integration through NTO. Gardner formally requested for his country to join, but was denied by the west, which had the affect of weakening the advocates of détente in the United Commonwealth.

Besides the tension among the two power blocs, there was a divergence between the North American and European democracies in the 1960s. Warren and von Schliefen both wanted to create a Europe that is integrated economically and politically, which included Britain as a fully European power in addition to North France, Germany, and Russia. But no organization comparable to the CAS in North America was created during the past decade because of disagreements among the European countries. The British Establishment of the early 1960s still held on to pretenses that Britain was a world power, and prioritize the special relationship with Sierra, the CAS, and its British Commonwealth allies, over the relationship with continental Europe. The smaller European nations feared being dominated by a Berlin–Moscow–Paris alignment, which was really an extension of German power, as Germany was the largest economy in Europe by 1960. Russia was culturally indecisive after its defeat in the war and wanted to avoid any leadership role, and North France, while still an important economic engine in Europe, was simply too weak after its colonial wars and the division of the country to be compared to Germany. They and the British also had holdouts that were interested in clinging on to their colonies, while Germany did not want to get dragged into their wars and prioritized European development and security. John Avery encouraged the British Establishment in its delusions about still being an empire to get the Europeans committed to supporting Sierran anti-Communist wars in the Third World, but Earl Warren recognized that the smaller European countries would only accept a European Economic Community (EEC) if Britain recognized itself as a European power and served as a democratic counterweight to Germany, Russia, and North France within the EEC. Warren saw Europe as the most important theater in the Cold War outside of North America, and believed that a European integration project would be a more important anchor for stability in the continent than the existing Anglo-American alliance. Conservative Prime Minister David Wood was reluctant to commit Britain to any larger European structure, but his Labour successor in 1964, Reginald Land, favored the integration project.

The creation of the European Coal and Steel Community between North France and Germany in 1948 was the first step taken towards a federal European structure. It was expanded to include the Netherlands and Luxembourg in 1950. However, the ECSC did not develop its own governmental structures, except a council of members appointed by the national governments. By 1951 the trade barriers for certain commodities among the four members of the Community had been abolished. The next step was taken in 1952, when Sierra demanded that North France rearm and create ten divisions for European defense, under NTO command. The Germans, who feared a resurgence of French militarism, wanted to create a European Defense Community (EDC) that would put North French forces under their command. Germany had similar concerns about Russia, which was permitted, by Sierran encouragement, to create a defense force of over 250,000 with the primary focus of defending its Far East, where Mao's China was becoming aggressive with its neighbors, and had border disputes with the Russian state. Britain did not become a member of the EDC, with Conservatives objecting to plans to create a separate European parliament and European cabinet, as proposed by Germany, while North France prioritized its wars in Algeria and Indochina over European defense. The EDC project did not get off the ground until after the Sierran intervention in the Vietnam War, when the situation had changed considerably. The Suez Crisis in 1960, the independence of Algeria in 1962, and the new Labour government in Britain in 1964 created enough political support for expanding the Coal and Steel Community. The ECSC became the Western European Union in 1961 for the purpose of increasing economic integration and to oversee North French rearmament in Europe, as French troops returned from Indochina and Algeria. The original four members were also joined by Denmark, Norway, and Sweden in the WEU. In response to this, Italy, the Iberian Union, and their other regional allies created the Mediterranean Union as their counterweight.

Having accepted a North French rearmament, Germany pushed for the prevention of North France from using it for the wrong purposes, and pushed for the creation of a larger EEC that would include political and military institutions. In Britain, Reginald Land also reassured the Germans by agreeing to keep three British divisions in France and one in western Russia until the year 2000. This allowed the reform of the Coal and Steel Community into the EEC, by the Rotterdam Treaty of 1967. In the end, the political institutions of the EEC were limited to making economic regulations, and the military structure was not formed because of continued disagreements and the reliance of all member states on the existing NTO. The EEC allowed for more efficient trade between its member states, and contributed to the postwar European economic miracle, with growth rates and a standard of living exceeding that of Italy or Iberia by a wide margin in the late 1960s. Britain, with its Labour leadership recognizing that the Commonwealth countries did not want to accept exclusive British decision-making on political and economic issues, and looking at Sierra using its influence against Britain during the Suez Crisis, agreed to join the EEC. The effect of the United Kingdom joining the Community was the improvement of its own economic situation considerably, and by 1970 relations between the EEC and the CAS had overcome their difficulties in the early part of the decade.

The Sino–Continental split

As the Vietnam War was becoming unpopular in Sierra and Europe during the late 1960s, another factor helped bring about the resolution of that conflict. The social and domestic reforms of Rupert Gardner in the United Commonwealth contrasted those of Mao in China, with Gardner's acceptance of capitalism in the Manhattan special economic zone, the decentralization of government, and democratic socialism being seen as a betrayal by Mao. Landonism, the official ideology of the United Commonwealth, permitted these changes, while the Chinese interpretation of orthodox Marxism stuck to a more authoritarian and centralized approach. In foreign relations, Mao wanted confrontation with the west while Gardner favored cooperation, although, this ironically led to the opposite occurring. The United Commonwealth was initially hesitant to support Mao's approach to supporting North Vietnam militarily, and did not publicly back China during the invasion of Tibet in 1959, nor during its border war with India in 1961–1962. The Chinese wanted to secure the Aksai Chin region to improve their position near the Central Asian states that gained independence from Russia, but still depended on Russia for their security. This was an effort to relieve the pressure from Russian forces on China's northern border. But the Chinese war was seen as unjustified aggression internationally, and Gardner used the opportunity to bring India closer to the Communist Bloc. In the aftermath of the Sino-Indian war, the disagreement between China and the United Commonwealth was becoming more public, with Mao accusing Gardner in 1963 of betraying the revolution, going back on orthodox Marxism and being weak with his reluctance to support the North Vietnamese in their fight against Sierra. Gardner believed that Mao represented the old ways of Callahan and Crawford, and was too cavalier about risking nuclear war with Sierra.

By 1965 the split that was growing between Mao and Gardner was becoming unbridgeable, and China was actively seeking to expand its own influence in the Communist bloc at the expense of the United Commonwealth. Its appeal in the Third World was that the Chinese experience was more relevant to them that the more developed United Commonwealth. The two countries still continued to cooperate on supporting the North Vietnamese, but as the Vietnam War entered into negotiations phase in 1969, China established its own Shanghai Pact as a counter to the U.C.-dominated Chattanooga Pact. By 1975, its membership included North Vietnam, Myanmar, Indonesia, and Laos. The split between the two countries was used by the West. After the 1969 election, Warren was succeeded by Kovrov Stoyanovich, who was interested in ending the Vietnam War and appointed Henry Kissinger as Avery's replacement at the Foreign Ministry. This was continued by his successor, when Stoyanovich was removed from office less than a year later for a corruption scandal. Kissinger made a secret trip to Beijing in the summer of 1970 to begin talks with North Vietnam's main backer, also in part due to him being an associate of the banker David Rockefeller, who had visited China in the 1960s and met with Mao on several occasions. Rockefeller, who went as far as praising "the incredible success of Mao's experiment" in an op-ed for the Porciúncula Times in 1964, saw immense potential for an economic relationship between Sierra and China, which he believed was achievable because of the growing differences between China and the Continentals. Accordingly, Kissinger conducted secret talks with China from 1969 to 1970, culminating in his visit to Beijing that summer, which itself was a precursor to Walter Zhou's official meeting with Mao in 1971. Initially the Kissinger visit did not yield much progress, and the Vietnam War actually intensified under Zhou between 1970 and 1973. The Zhou ministry, through Kissinger and (indirectly) Rockefeller, persuaded Mao to cooperate by pressuring Ho Chi Minh to negotiate, while doing the same with South Vietnamese president Nguyễn Văn Thiệu, who wanted to keep Sierran troops in his country.

Sierra began removing its forces from South Vietnam, but not before making the country a full member of SEATO as a guarantee of its continued security, while North Vietnam ended support to the Viet Cong and pledged to not undertake any aggression against the state. The Paris Peace Accords of 1975 formally ended the conflict, and included the North–South Vietnamese Joint Declaration, by which they ended their claim over each other's sovereignty and pledged to respect their borders. Conflicts still continued in Laos and Cambodia, but Sierra was able to remove the bulk of its forces from South Vietnam. Kissinger also met with Tondolese dictator Ferdinand Ho and was able to get his commitment to using SEATO intervention forces to protect South Vietnam in the event of any renewed Communist aggression. The result of Kissinger's and Zhou's work was that by 1975, the end of the Vietnam War facilitated the establishment of diplomatic relations between China and Sierra and began the groundwork for the eventual opening of China to Western investment. From 1970 China and the United Commonwealth switched roles, with Mao pursuing cooperation with the west while making a show of belligerence, while the U.C. became more hostile, especially after Gardner's death. The United Commonwealth, led by the neoconservative Charles Acker from 1968, who rose to power in the Party's reaction to the Gardner reforms, was unable to fix the relationship with China because the damage had already been done. The division of the Communist Bloc into two camps after 1970 was more serious and consequential than the earlier disagreements between the European and North American democratic states.

New Cold War

From two blocs to three

In the two decades between the Chinese Civil War and Walter Zhou's state visit to Beijing in 1971, most of the major Cold War conflicts had been precipitated by the aggression of Maoist China. After about 1970, the main focus of Sierra would once again be on its competition with the United Commonwealth, as the disagreements between Mao Zedong and the Continentals allowed Western leaders to create a rift between the two largest powers of the Eastern Bloc. This would become the "new" phase of the Cold War.

The victory of the Sierran Royalist Party in 1969 led to the development of Earl Warren's gradual deterrence into what became the realism of Walter Zhou and Henry Kissinger. Having achieved the "balance of terror" in the nuclear arms race, and set up a series of paper triggers on the periphery of the Communist powers with the NTO in Europe and North America, CENTO in the Near and Middle East, and SEATO in the Far East, Sierra experienced close calls with nuclear war in the Irish Missile Crisis and in the conflict over Vietnam (for a time, Alfred von Schlieffen had two Sierran aircraft carriers positioned in the the South China Sea with atomic bombs, as a warning to Mao). Earl Warren began the process of ending the hostilities in the Far East, and his efforts were continued by the administrations of Kovrov Stoyanovich and his successor, Walter Zhou. The rapprochement between Sierra and China in the early 1970s was made possible by John Avery's successor Henry Kissinger, who recognized that the Chinese regime had two chief concerns: preserving the power of the Communist Party in their own country, and surrounding themselves with subordinate vassal states that were loyal to China. As a realist, not an anti-Communist ideologue like his predecessor, Kissinger believed that Sierran national interests were not threatened by either of those goals. A third concern, advantageous to Sierran interests, emerged only in the late 1960s, which was establishing China as an intellectual and moral rival to the U.C. for leadership of the Communist world.

The Space Race appeared to supersede the nuclear arms race in importance in the 1970s when the United Commonwealth landed the first man on the Moon in 1969. Sierra's Royal Aeronautics and Aerospace Administration scrambled to achieve its own manned lunar mission, occurring in 1971, and the next several years trying to launch a similar mission to Mars. On the nuclear front, after the development of ICBMs in the early 1960s, missile arsenals of both countries gradually shifted from intermediate range to intercontinental range, creating an equilibrium, as the importance of military bases immediately near another country was no longer as important. By 1970, another race was underway by the navies of the major powers, but particularly by the Sierran Royal Navy and the Continental Navy, for more advanced stealth submarines that could serve as undetectable launch platforms for ICBMs. This and the Space Race also helped refocus Sierran attention back to the rivalry with the United Commonwealth.

In China, the famines that were caused by a deficit in food production, exacerbated by the devastation of the war with Japan and the following Civil War, had been overcome by the start of the new decade. Lysander Hughes and Rupert Gardner assisted the Chinese by sending large quantities of food and technical assistance for agricultural development, including through OMEAD. Improved production techniques, increase of imports from China's new regional allies, and a reduction in population growth assisted in stabilizing the situation. Mao, having used the nuclear race between Sierra and the U.C. as a cover to launch wars of liberation and communism against China's neighbors, established friendly governments in Laos, North Vietnam, and indirectly, in Indonesia and Burma. The ideological differences between Mao and Gardner, culminating in the creation of the Shanghai Pact in 1969, signaled that assistance from the United Commonwealth was no longer needed to sustain China. Kissinger took advantage of this to restart diplomatic ties between the PRC and Sierra in 1971. With a deescalation in the Far East, the Royalist administration entrusted a remilitarized Japan and SEATO to maintain the defense of allied democracies in the region, as Sierra turned its attention elsewhere. Japan, which underwent an agricultural revolution by implementing more efficient methods of production with Sierran assistance, was rapidly becoming an industrial giant, and shifted its trade from neighboring states for raw materials to trade with Europe and North America for more advanced manufactured goods, and with the Middle and Near East for oil. The Japanese armed forces, rebuilt with the help of Sierra, were capable of matching the PLA.

Relations between China and Sierra continued on the upward trajectory for the rest of the 1970s, especially after Mao's death in 1976. Zhou Zhiyong succeeded him as the leader of China and took the relationship even further. Rong Yiren, Zhou's vice president and the head of the China International Trust Investment Corporation (CITIC), would meet with David Rockefeller when he became the head of the Bank of Sierra, and created the preliminary deals for the beginnings of the investment and technology transfers from some of the leading CAS-based corporations to China. Not only did Western companies move manufacturing to China, but their research and development functions as well. One key point of the deal was that Western companies had to share their technology with China in order to have access to the Chinese market and its industrial capacity. This way, the agreements negotiated by Rong Yiren and Rockefeller were what enabled the massive economic growth and technological advancements in China between 1990 and 2010. Sino–Sierran ties continued to increase in this manner until the early 1980s, when they experienced difficulties as Zhou began reverting to policies reminiscent of Mao over a new regional crisis, and therefore the true opening of China is not considered to have fully started until the early 1990s. However, from 1970 to the 1980s Kissinger took advantage of the growing closeness with China to use as leverage against the United Commonwealth.

Latin America in the competition

The Western Hemisphere, and especially Latin America, became to Sierra in the 1970s and 1980s what the Far East had been in the 1950s and 1960s. Latin America was a source of political instability and a ground for Sierran–Continental great power competition since the 19th century, though it was not until the couple of decades just prior to the Great War that the North American states became strong enough to challenge the Europeans for control over the area, and prior to the 1970s it was often overlooked by Sierran policymakers in the context of the Cold War. Being larger than the CAS and the United Commonwealth combined, and having a slightly bigger population by 1960, Latin America was a rapidly growing developing economy in the middle of the 20th century. Like many other parts of the Third World, its main difficulties came from a food supply that was unable to sustain its population, a structure of socioeconomic organization that was unable to cope with increasing Western intrusions, a low standard of living from the lack of economic or technological development, and the introduction of modern weapons and new radical ideologies. By 1960 the wealth inequality in Latin American countries was one of the most extreme in the world, with poverty for the vast majority of people except an elite at the top, and a small professional middle class in between to service the elite. The wealthy upper class that owned much of the land and monopolized the income from the region's productivity rarely invested the money into improving the conditions of their own countries. With the existing systems not able or willing to change this situation, since the early 1900s Marxism-Landonism began taking hold among Latin American revolutionary movements that rallied against the upper classes, propped up by their allies from Sierra and other North American countries that benefited from cheap resource extraction.

The Continental Revolutionary War created a Communist nation that was willing to be a powerful ally to these revolutionaries. The revolution began in Mexico, where a Civil War broke out in the 1910s after the Second Mexican Empire entered a period of decline. Mexico was briefly divided, but reunited under a Landonist regime at the end of the Great War. With Mexico becoming an ally of the United Commonwealth, Sierra, and specially its southern possessions in the Caribbean, were under military pressure. These included Cozumel, the Saint Andrews, Providence, and the Corn Islands, and the remnants of the old Federalist regime from the United Commonwealth, in exile in the Antilles since 1921. The Antilles under President Amelia Abarough in the 1970s were a combination of typical Federalist Party despotism with an economic system modeled on the northern European states and Japan. Connecting these to the Sierran homeland was the Nicaragua Canal, cutting through the Central American isthmus. To achieve strategic depth against Mexico and defend the Canal, the Royal Intelligence Agency spent much of its early history setting up brutal military dictatorships in the Central American "banana republics" of Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, and Nicaragua. There the RIA worked with the Antillean Central Intelligence Agency, in support of the Antilles-based United Fruit Company, a corporation that owned much of the land and infrastructure in Central America. This was accomplished by partnering with the upper class oligarchy of army officers, landlords, bankers, and Catholic clergy, which was able to keep local revolutionaries from mobilizing a passive population against them. For instance, in Guatemala, the RIA and the CIA cooperated to overthrow a leftist reformer who attempted to nationalize land owned by United Fruit in 1954, with the help of the Guatemalan military and a group of exiles that invaded from the adjacent dictatorships of Honduras and Nicaragua.

Their success against communists in Central America during the 1940s and 1950s convinced the RIA that it could continue to bottle up revolutionary movements using the local oligarchs and political exiles. Gran Colombia, covering the northwest portion of South America and bordering the Sierran-allied Costa Rica to the north, was ruled by a military government that was friendly with Sierran business interests up until the late 1950s. The ineptitude of its leaders led to its replacement with a reformist liberal president and parliament, though they still only represented the oligarchic upper class, and were incapable of preventing Communist insurgency from gaining ground in the rural areas. A coalition of left-wing parties known as the National Front began resorting to violence and corruption to maintain its own power amidst disagreements with the Communists. This turned into open war in 1968, and in 1969 the Communists seized oil fields in the state of Venezuela and copper and tin mines in Peru, run by Western companies. In the parts of Gran Colombia that they controlled through local people's committees, the Colombian or Andean Communists engaged in education campaigns to decrease illiteracy, opened hospitals with Continental assistance, built new schools, cut utility costs, and imposed land reform. The policies had a mixed record of success, but they provided enough improvement to gradually undermine support for the National Front government in Bogotà, and their attacks on oil fields and mines in 1969 created instability in the National Front-controlled areas. In April 1970, the rebels took control of the central government, reducing National Front loyalists to a few remote corners of the country, and exiles in neighboring Brazil and Costa Rica.

Thinking that they could repeat the coup in Guatemala, the RIA under the direction of Walter Zhou was given permission to use force in Gran Colombia to restore the National Front to power. The initial RIA plan there was based on the misunderstanding that the Guatemalan "Communists" had been removed by the raid of Sierran-armed exiles from Nicaragua into Guatemala. In fact, the leftist elected government was removed by its own army, using the invasion of exiles as a pretext. RIA Director James Kerr believed that a raid by Andean exiles, representing the rich oligarchy that had been displaced, could remove the Communists from power. Instead, in July 1970, the groups of exiles were defeated by local people's committees within three days of crossing the Brazilian and Costa Rican borders. The failed invasion damaged Sierran credibility, strengthened the image of Communist strongman Camilo Velázquez across Latin America, and ultimately allowed his new state – the United People's Committees – to form a close alliance with Charles Acker's United Commonwealth. After this debacle, Zhou and Henry Kissinger authorized Operation Condor, a broad plan to use covert means, black ops, and military action to remove left-wing governments from power in Latin America, including the Andes. As part of this, in September 1970 the RIA orchestrated a false flag attack by disguised Andean paramilitaries and civilians on the Sierran embassy in Bogotá, to create pretext for more direct Sierran involvement. The plan was first proposed by James Kerr to Walter Zhou, and was also supported by the Joint Chiefs of the Defense Staff.

A military intervention in the Andes would have been a violation of the New Orleans Accords, an agreement signed between Sierra and the United Commonwealth in 1937 that allowed them to have a fragile working partnership against derzhavism. Among its conditions was a pledge to not use military force to resolve political disputes in the Western Hemisphere, and especially south of the Sierran and Brazorian borders. The New Orleans Accords had already been violated by the United Commonwealth during the Cuban insurgency in the Antilles and by Sierra during the coup in Guatemala. In addition to the Accords, Sierran prime minister Poncio Salinas declared that Sierra would follow a "Good Neighbor policy" with regards to Latin America in 1941. He proposed ending Sierra's legacy of interventionism in the region, in favor of promoting economic, humanitarian, and technical assistance to help develop the countries of Latin America. It was partly inspired by the Food for Peace program of the United Commonwealth. Although it was never officially rescinded, the Franklin Tan administration effectively stopped following the Good Neighbor policy in the early 1950s. Sierran public opinion supported an intervention in the Andes after the embassy attack, and the Andes Resolution passed by the House of Commons authorized Zhou to use military force to restore the "integrity of Gran Colombia" and to retaliate against "Communist aggression."

In November 1970, Sierran Royal Marines landed on the Galapagos Islands, occupying them quickly to use as a base for operations in the intervention. The state of Peru had the most opposition to the Andean Communists, and was identified by the RIA as the most favorable location for landing Sierran ground troops. Over the next few days, Marine and Army units were landed in Ecuador and Peru, and the major cities of Quito and Lima were occupied with limited resistance. The Andean People's Army had entrusted local militias to maintain control over many areas, as these had been the basis for the success of the Communist movement against the National Front. General Alfonso Tejero, the former National Front defense minister, was appointed as the head of the "legitimate" Gran Colombian government in Quito, and he formally asked Sierra for more military assistance. The Sierran military had learned from its experiences in Vietnam, and was more accustomed to fighting in jungle terrain against insurgents. However, with the exception of the coastal lowlands, central Peru and Ecuador were very mountainous, with the country's interior being separated from the coast by massive mountain ranges that had limited rail and road access. The Andean People's Army took advantage of this, being able to ambush Sierran troops and supply lines in the mountains, while raiding the coastal cities controlled by them and the National Front. As the Sierran military failed to make progress, the initial support for the war among the Sierran people began evaporating.

As the Sierran war in the Andes dragged on, it provoked a resurgence of anti-war sentiment in Sierra, similar to that of the Vietnam era. As the last Sierran troops left Vietnam by 1975, there was a growing call to leave the Andes as well. In 1975, the Democratic-Republicans defeated the Royalists, portraying the Andean conflict as a "Royalist war." When Kirk Siskind entered office after Zhou, he began negotiations, leading to the Kingston Accords, by which Sierra ended its participation and allowed the National Front to continue its own war against the Communists. Within months, the remnants of the anti-Communist forces were defeated and Velázquez reestablished control over the entire country. However, Siskind, at the advice of Henry Kissinger, continued to provide arms and other assistance to rebels during the Second Mesoamerican War in Mexico, where regional separatists attempted to gain independence from the government in Mexico City. Overall, Siskind began moving towards a détente with the United Commonwealth in the second half of the decade. At the same time relations with China began taking a downturn over a new crisis in the Middle East.

Continental Empire and Red China: 1980s

After the death of Mao Zedong in 1976, the Eight Elders of the Communist Party in China, the most prominent leaders of the party and veterans of the revolution that assisted Mao's rise to power, installed Zhou Zhiyong as his successor. Initially Zhou began implementing economic and political reforms that Mao had refused to do, policies along the lines of the Gardner reforms in the United Commonwealth, but in the late 1970s the influential Maoist hardliners among the Eight Elders turned against it. Zhou was the most senior member of the Eight Elders and was Mao's top economic adviser, and wanted to take China in the direction of state-directed market economics, but the second and third most powerful Elders were still committed to orthodox Marxism. An opportunity arose in 1977 for them to being wrest back control over the Party from Zhou and the other reform-minded Elders. When the Kirk Siskind ministry took office in Sierra in 1975, it was guided by an ideology of universal human rights and democratic values, and Henry Kissinger's successor as Foreign Minister, Winston Locke, was a strongly committed liberal idealist and anti-Communist who believed in the Containment doctrine. Locke, a Superian by birth who grew up in Continental-occupied Superior during the Great War, took a hardline position on relations with both China and the United Commonwealth. When he wrote Siskind's first major foreign policy speech, it called for Sierran support for the Continental democracy movement and Chinese dissidents. Kissinger, who became Siskind's National Security Adviser, became an opponent of Locke in the administration, who argued for ignoring Eastern Bloc human rights violations to facilitate a détente with China and the United Commonwealth.

The western Chinese region of Xinjiang had experienced separatism and ethnic violence over the centuries since the Qing dynasty first established its control over the area in the late 18th century. The region was stabilized until the start of the Warlord Era, when it fell under the rule of local warlords and various factions, and the political chaos in the remote province continued through the Second Sino-Japanese War and the Chinese Civil War. Russia sponsored the existence of the quasi-independent Second East Turkestan Republic in northern Xinjiang during the Civil War of the 1940s, which was ruled by a coalition of different groups and parties that were mainly united in opposition to Communism and to Chinese rule over the region. In the 1950s the People's Republic of China restored full control over its periphery, including Mongolia, Tibet, and Xinjiang. Tens of thousands of ethnic Kazakhs and Uyghers that supported independence were expelled across the border, and ended up in Kazakhstan or Tajikistan. Among the three Central Asian states that gained independence after the Great War, Kazakhstan became the most closely linked to Europe economically, through Russia, and was influenced by the Allied Control Council-implemented reforms in that country after the war. Kazakhstan followed a similar path of political development to Russia, while the landlocked and more isolated countries to the south, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan, became dictatorships. Although democratic Russia, which joined the NTO and was linked with the west, continued to be a rival of China, it normalized its relations in late 1962, when Prime Minister Nikolai Kozyrev traveled to Beijing to meet with Mao. As part of their agreement to deescalate tensions, Russia ended its support to "Turkestan" nationalist organizations and pressured the government of Kazakhstan to do the same. The remaining nationalist groups took refuge in Uzbekistan and Tajikistan.

The Final Years

Aftermath

In popular culture

Shortly after the start of the Cold War, the Kingdom of Sierra and the United Commonwealth began mass production of propaganda against one another. The propaganda produced by each state was designed to expand their own influence both regionally and globally, with examples including songs, literary works, and the production of motion pictures. The propaganda within the United Commonwealth typically promoted more traditional aspects of culture, as displayed in major films that depicted Sierra as evil under the style of Continentalist realism.

See also

- Second Cold War

- Great War

- Sierran imperialism

- Continental empire

- Mitteleuropa

- Red Scare

- Crimson Scare

- Continental espionage in Sierra

- Sierran espionage in the United Commonwealth

- Outline of the Cold War

- Timeline of events in the Cold War

- War on Terror

| This page uses material from the Wikipedia page Cold War, which is released under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License (view authors). |

- Start-class articles

- Altverse II

- Cold War

- 20th-century conflicts

- Global conflicts

- International relations

- Geopolitical rivalry

- Wars involving the United Commonwealth

- Wars involving the Kingdom of Sierra

- Wars involving China

- Wars involving the NTO

- Wars involving the Landonist International

- Wars involving the CAS

- Aftermath of the Great War

- Nuclear warfare

- History of NTO

- 1950s neologisms

- China–Kingdom of Sierra relations

- Kingdom of Sierra–United Commonwealth relations

- China–United Commonwealth relations