1981 oil crisis

In September 1981, the members of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries, led by King Faisal II of Hashemite Arabia, declared an oil embargo against countries that supported Palestine's decision to bring Jerusalem back under its direct control. The initial nations targeted were France, Sierra, the United Commonwealth, the United Kingdom, and Italy, and was later extended to Spain and Germany. By the end of the embargo in April 1982, the price of oil increased by over 300%, from KS$3 per barrel to $12 per barrel. The embargo caused a global oil price "shock" that had long-term consequences for global politics and the global economy. It is sometimes called the "first oil shock" because a second one occurred in 1984 after the outbreak of the War in the Levant.

The effects of the oil crisis continued for the rest of the 1980s, until an oil glut led to a fall in prices in the early 1990s. The 1981 oil price shock, combined with the one that occurred three years later, ended the uninterrupted increase of North American and European prosperity that began in the years after the Great War.

Background

Status of Jerusalem

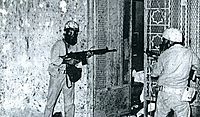

The cause of the crisis was the governance of the city of Jerusalem, especially its Muslim Quarter. In May 1981, a group of Sunni Islamic extremists affiliated with the Palestinian Islamic Jihad movement seized control of the Al-Aqsa Mosque on the Temple Mount in Jerusalem. They demanded that Palestine be returned to a strict interpretation of Sharia law and for the ruling Arab Nationalist Movement end its control over the Palestinian state, and restore power to an Islamic government. After a siege that lasted nearly one month, the Palestinian Army, assisted by British SAS and French GIGN commandos, stormed the mosque to retake control of it from the terrorists. The immediate affect of the crisis was that the Palestinian government, led by the Ba'ath Arab Nationalist Movement, ordered the Muslim Quarter, that was previously self-governing under its own Supreme Muslim Council since 1970, to be placed back under its direct control.

Although Palestine was a close partner of the United Commonwealth, Egypt, and the Eastern bloc, its government received support during the crisis from the Western countries, including France, the United Kingdom, and Sierra. Among these, Sierran Prime Minister Kirk Siskind openly provided support to the Palestinian government during the crisis, and offered Sierran assistance to the effort to retake the mosque. He also worked closely with Egyptian leader Anwar Sadat and the Continental presidents Christopher Yeager and Simon Valure, who succeeded Yeager at the start of October 1981. But in Hashemite Arabia and other conservative Islamic parts of the Arab world, those that seized the mosque were seen as martyrs, as Palestine was considered to be under the occupation of a socialist and secular government. The Hashemite monarchy saw the the action of the Siskind ministry, as well as the French and British governments, as a betrayal from their allies. King Faisal II asked Siskind to assist him in opposing the Arab Nationalist Movement bringing the Muslim Quarter to the control of a secular government instead of the Supreme Muslim Council, which was rejected by the Siskind ministry.

Decline in Anglo-American production

During the 1970s, oil production in Anglo-American countries, both those of the CAS and the Chattanooga Pact, was not able to keep up with the amount demanded by the growing usage of motor vehicles. The difference was made up for on each side from the Arab Gulf states, Iran, the United People's Committees, Mexico, and smaller producers in Africa, including Angola and Algeria. In Europe, Russia and Norway were increasing their oil production, but as of 1981 the continent still depended on the Middle East for additional oil. Sierra and its CAS allies depended extensively on oil imports from overseas, with over 75% of Sierran oil coming from the Middle East, while the United Commonwealth's leadership followed a policy of relying more on Andean and Mexican imports.

OPEC and the "oil weapon"

OPEC had been created in 1975 to help stabilize the price of oil on the markets in the years after the Great War, consisting of Hashemite Arabia, Iraq, the Trucial States, Hasa, Iran, and Bahrain. Over the next decade they were joined by Azerbaijan, Sudan, the Delta Republic, Equatorial Guinea, and Gabon, in an effort to stop the oil price from being manipulated by "independent oil companies". As the value of the Sierran dollar declined in the 1970s due to inflation, OPEC announced they would price oil in a certain amount of gold.

Arab countries attempted to use oil as leverage in previous occasions. During the Suez Crisis in 1960, when Britain and France invaded Egypt, Palestinian guerilla fighters attempted to destroy the Trans-Arabian Pipeline in neighboring Syria, disrupting the supply of oil to Europe. The oil disruption had a negligible effect on the crisis, as the pressure from the Conference of American States and the United Commonwealth led to a British and French withdrawal from Egypt. The Hashemites were against the use of oil as a weapon, as they depended on Western support to defend themselves from the growing threat of Nasserism, and they were aware of alternative sources of oil in Africa and South America. It was initially the revolutionaries in Egypt and Libya that favored this strategy, since the Suez Crisis.

The two most powerful leaders in the Arab world at the time, Egyptian president Anwar Sadat and Hashemite King Faisal II, cooperated on many issues during the 1970s. Sadat and Faisal were both pious Muslims, and Sadat ended the suppression of anti-socialist and Islamic traditionalist forces in Egypt. However, Sadat made an effort to improve Egypt's relations with the capitalist West, which Faisal believed could harm Hashemite Arabia's alliance with Sierra. But the main disruption to the Egyptian-Hashemite detente came from the Al-Aqsa mosque siege in the spring of 1981, when Sadat backed the Palestinian government in its response to the event. Sadat spoke with Kirk Siskind and other Western leaders, convincing them to support the Palestinian restoration of direct control over Jerusalem, even though this went against League of Nations Resolution 203 from 1970. In the summer of 1981 a Hashemite delegation arrived in Sierra, telling Minister of Foreign Affairs Winston Locke and National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger that Hashemite Arabia would suspend oil sales to Sierra if the Sierran government did not oppose Palestine's plan to bring Jerusalem under direct rule. Kissinger believed that the Hashemites were bluffing, and the Siskind ministry considered improving relations with Egypt to be more important. The Palestinian government went ahead with its plans in early September 1981, dissolving the Supreme Muslim Council without consulting with the Hashemites, the Council's main benefactor.

On September 17, 1981, Hashemite Arabia and OPEC cut their oil production by 5% and announced the start of an embargo on Palestine's supporters, including Sierra, the United Commonwealth, Italy, Spain, France, the United Kingdom, and Germany. King Faisal's Foreign Minister Majed al-Aiban visited Porciúncula on September 26, telling Siskind, Locke, and Kissinger that Hashemite Arabia will end its embargo once the Muslim self-governance in Jerusalem was restored and the secular Palestinian government ended its rule over the Muslim Quarter. Siskind promised al-Aiban that he will work on mediating a solution acceptable to all sides, who delivered the message to King Faisal II. He felt that this was not enough, and that his efforts to fight communist influence in the Arab world were not being appreciated by the Sierrans. On September 30, the king announced the start of the embargo, which was joined by all other major oil producers in the Middle East and North Africa except Libya, Algeria, and Syria.

Course of the embargo

The embargo lasted from September 1981 to April 1982. During a visit to Cairo on October 1, 1981, Henry Kissinger – who was directed by Siskind to resolve the embargo – spoke to Anwar Sadat for advice on negotiating with King Faisal. Sadat told him that Faisal's biggest hatred was communism, and that the king believed that Palestine was involved in a Marxist–Landonist conspiracy against Islam. Faisal believed that the Arab Nationalist Movement had been influenced by the Continentalist Party of the United Commonwealth, and had a pan-Arab vision that was based on Continentalism, which threatened the entire Islamic world. Kissinger told this to Siskind in mid-October upon returning to Sierra, who spent his administration improving Sierra's relations with the United Commonwealth, and the prime minister saw Faisal as an obstacle to his foreign policy.

When Kissinger arrived in Riyadh for a meeting with Faisal in late October, he wanted the Hashemites to lift the embargo in exchange for a promise from Siskind to be evenhanded in negotiations with the Palestinians about the governance of Jerusalem's Muslim Quarter. Faisal ignored Kissinger's efforts to get him to lift the embargo and told him that "Sierra made mistake by siding with the United Commonwealth against us twenty years ago. Nasser brought Communism to the Arab world, and since then it has spread across the greater Middle East, including Palestine. If Sierra had reacted the same way as Britain and France did, we would not be in this crisis." Kissinger left Riyadh without any agreement. At a summit of the Organization for Islamic Cooperation, King Faisal was praised for standing up to the West to defend the holy places in Jerusalem. The embargo was extended in November to any country that expressed support for the Palestinian government.

Hashemite Arabia had a reason to resolve the crisis, however, because it dependent on Sierran weapons and kept its money in Sierran dollars, which would lose value if the crisis led to inflation. In November and December 1981, Sierra and League of Nations representatives negotiated with Palestine and Egypt, using their influence to reach a deal that was accepted by the Hashemites and the Supreme Muslim Council. The Riyadh Agreement, signed on January 7, 1982, led to the creation of a League of Nations Commission to oversee the implementation of a multi-confessional system of government, with each quarter having its own local system in accordance with its religious traditions. The full implementation of the deal took another few months, so Hashemite Arabia did not lift its embargo until April.