Chinese Civil War

| Chinese Civil War | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Cold War | |||||||||

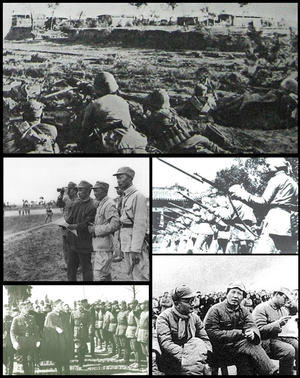

Clockwise from the top: communist troops at the Battle of Siping; Hui Muslim soldiers of the NRA; Mao Zedong in 1939; Chiang Kai-shek inspecting soldiers; CCP general Su Yu inspecting troops before the Menglianggu campaign | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

Supported by: |

Supported by: | ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

4,000,000 regular 2,300,000 militia |

1,500,000 regular 2,800,000 militia | ||||||||

| Part of a series on the |

| History of China since 1911 |

|---|

|

|

List

|

|

1911–1927: Early Republic of China |

|

1938–1949: Chinese Civil War |

|

1949–1964: Mao Zedong's China |

|

1964–1999: Reform and Fall of Communism |

|

Related topics |

|

China portal |

The Chinese Civil War was a civil war in China that was fought between the Kuomintang (KMT)-led Nationalist Government and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) for control over Mainland China the war lasted from 1938 until 1949 and began following the end of the Second Sino-Japanese War where the CCP, led by Mao Zedong, rose up in revolt against Chiang Kai-shek and the Nationalist Government, lasting from February 1938 to October 1949, ending with the establishment of the People's Republic of China.

The peace between the Kuomintang and the Communists immediately after the Sino-Japanese War broke when a Communist-inspired uprising in Wuhan was brutally suppressed by the Nationalists, leading to all-out war being fought across the Chinese Mainland. Due to troops of the Japanese Army being present in areas of Eastern China, they would support the Nationalist Government, but were purely defensive in their military operations seeking to protect occupied coastal territories, Manchuria, and Korea, but did give aid and support to the National Revolutionary Army in their fight against the CCP and the People's Liberation Army. Other foreign powers, mainly participants from the Great War, supported their respective sides. The war ended in 1949 with the capture of the mainland and the proclamation of the People's Republic of China by Mao Zedong, ending the war in a communist victory.

In the early stage of the war from 1938 to 1944 the CCP focused on consolidating its control of the countryside in northern and central China, away from the larger cities on the coast. The Communists avoided direct battles with the Kuomintang and attacking its strong points, and were willing to abandon territory temporarily. By disrupting the supply lines between the Kuomintang-controlled large cities and taking the rural countryside that produced food and other resources, the Communists were able to wear out the Nationalist Army. By 1945, the Chinese Red Army had increased to two million men and decided to go on the defensive. In the north, the cities of Jinan and Shijiazhuang were the first to fall in July 1945, and the Central Plains Campaign led to the capture of most of Northern China by December. In 1946 several large KMT armies were surrounded and defeated, giving the CCP heavy equipment and vehicles. From early 1947 until 1949 the CCP took control of the rest of the country aside from the eastern coast, with the KMT concentrating its remaining forces in Jiangsu, Zhejiang, and Fujian. The remaining cities fell one by one, and the Nanjing-Shanghai campaign in late 1949 led to the collapse of the Nationalist Government.

Following the end of the war, the KMT fled into exile with Chiang hiding in Japan and later in the Kingdom of Sierra for the rest of his life. The Japanese withdrew their forces from the mainland with the exception of Manchukuo and the China–Japan Basic Treaty was effectively nullified. Mao became the leader of China and the CCP would reign as the governing party for fifty years. During the Great War, the PRC would join the Allied powers against the Axis in the Korean War and would emerge as a major player in the Cold War leading a rival bloc within the communist world due to the PRC's adherence towards traditional Marxism over Landonism.

The Chinese Civil War would inspire the Communist Party of Manchuria to stage the Manchu Revolution, supported by the Manchu National Army, against Manchukuo to establish a communist state leading to the creation of the Manchu People's Republic. While there would be a brief period of communist solidarity, many within the CCP resented an independent Manchuria and sought its annexation, preventing full cooperation and a bitter regional rivalry to manifest during the latter half of the 20th century.

Background

The war between China and Japan in 1927–1938 brought to a head the problems that the country had been facing since the fall of the imperial regime in 1911 and, ultimately, since Western civilization came into contact with China very extensively in the 19th century. The difficulties that these events caused would ultimately be the reason for the Chinese Civil War. For most of its history Chinese society had been divided into a small imperial elite at the top, a large bureaucracy in the middle, and a mass of peasantry at the bottom organized into local villages. The peasant class lived a lifestyle slightly above subsistence level after all of the taxes and bribes to officials had been paid, letting them save some wealth, and there was a meritocracy in the form of imperial examinations that made advancement possible. The elite derived its wealth and power through a system of taxation of the peasants, but due to the vast size of the country, inadequate methods of transportation and communication, and the complexity of the Chinese writing system, this tax collection could not occur without a highly trained class of bureaucrats. The bureaucracy was formed to administer this system, and in return received a significant portion of the revenue through customary bribes, while the peasants at the bottom rarely felt any military or political force from the imperial elite as long as it received its share of the tax revenue. Because of this the imperial group received proportionately far less wealth than they otherwise would have, and more of it was left to the peasant and bureaucratic class, but due to of the vastness of the country what they did receive was still massive in absolute terms. Over time this created a tradition of relationships in Chinese society, and along with it, a culture that taught the people the importance of maintaining tradition above all else. Inefficiency and corruption were ingrained in this system, and there was no desire to make it more efficient because that would disrupt the delicate balance and put too much pressure on the peasants.

The problems emerged when China came into contact with European powers, whose economies were far more efficient, and that allowed them to project military power much more effectively. The existing Chinese structure could not provide large quantities of modern weapons, soldiers to use them, or rapidly industrialize when it had no adequate methods of communication or transportation across its massive territory, insufficient record keeping, and a strong incentive to keep the situation the way it was because that was the bedrock of society. In addition, the agricultural practices used in China were very outdated and inefficient, causing a smaller output despite a relatively larger share of the population involved in farming than in Europe or in North America, and there was increasing pressure on the food supply from the rapidly growing large population. The production of other goods in the economy by the peasant class was hampered when they were challenged by cheap Western factory-made imports, removing an important source of revenue for them. As these changes took place the conditions of Chinese peasants only grew worse from 1900 on, and made it harder for the majority of farmers, who rented land, to make rent payments to landowners. At the same time Western countries forced China to make concessions, both economic (not allowing tariffs on European imported goods) and political (giving up territory as European colonies). This created a powder-keg in society for revolution, and during that century China was increasingly plagued by massive rebellions against the ruling Qing dynasty, although most of them were regional ones that did not succeed in toppling the imperial government. They did devastate a lot of farmland and cities, making living conditions for the average people even worse. The societal preference for maintaining tradition helped keep the Qing keep the situation under control, and this was replaced after 1911 by optimism that the new republican regime could address the growing economic problems.

By 1911, when a series of mutinies financed by Chinese revolutionaries living abroad created a major crisis, much of the army leadership was unwilling to defend the Qing. After negotiations with the revolutionaries and the government, Yuan Shikai, the general in charge of the country's strongest and most modern army, the Beiyang Army, was able to get the abdication of the Xuantong Emperor. The Republic of China was declared in January 1912 and the revolutionary leader Sun Yat-sen returned to China, but he and the Western-educated intellectual class that had been agitating for the removal of the imperial dynasty remained isolated from any real power. The power remained in the hands of the army that possessed most of the weapons, leading to Yuan Shikai becoming president of the Republic of China. The imperial regime had deliberately kept the army weak without an effective centralized leadership to avoid a potential coup, and as a result there were strong regional and personal loyalties among the troops. Many of the generals had been placed into their positions by Yuan, which kept them loyal to his rule, but after his death the system completely came apart into warlordism from 1916 to 1927. During this period the republican government in Beijing nominally controlled all of China, but in reality its rule only extended to major cities and some of the coastal areas. Most of the interior was controlled by warlords, and the government itself came to be led by warlords through corruption and military force. Amidst the power struggle between different cliques of warlords, military commander Chiang Kai-shek and his Chinese Nationalist Party (Kuomintang) tried to form a new national government in the south of China to end this state of affairs. He received some financing from abroad and made an alliance with the wealthy landowner, banker, and merchant class of the country. Because of this the Kuomintang movement did not make any attempt to address the economic conditions of the masses but focused on fighting the warlords. However, in late 1926 and early 1927, the Imperial Japanese Army, which had been increasingly drawn into Chinese politics as the nationalistic leadership in Japan saw the natural resources of China as necessary to maintain the Japanese economy, openly intervened in north China in a dispute between rival warlords to place their preferred candidate in charge of the nominal government.

The Japanese invasion of China in 1927 led the outbreak of total war between the two countries, and united the Chinese people in resisting the attacker behind Chiang Kai-shek, who was recognized by the warlords as the leader of the country. The country became unified in spirit, though politically Chiang's power was still limited as it depended on the loyalty of the remaining warlords, who continued to control large parts of China. He proceeded to transform the republican government into an authoritarian Nationalist wartime dictatorship. Weapons spread to the public as millions of Chinese took up arms against the invaders, either in the ranks of the National Revolutionary Army of Chiang Kai-shek, or, increasingly, in the guerilla Chinese Red Army. The war lasted for more than a decade as the Japanese became bogged down, but from 1932 the military power of the Chinese Nationalist government declined from continuous fighting against the better-trained and -equipped the Japanese forces. The last major Japanese offensive, Operation 5 (in 1937–1938), captured the capital Nanjing and much of the economically-important central China from the Nationalists and caused so much damage that the Nationalist Army was left on the brink of collapse. This, along with the loss of supplies from his Western allies and the end of the broader the Great War, led Chiang to sue for peace and sign the unequal China–Japan Basic Treaty. Along with the massive loss of prestige from signing unfavorable peace terms, during the war the Nationalist government had become completely corrupt and hollowed out by officials who sought to make a profit for themselves, making any kind of institutional improvements to the Nationalist regime nearly impossible by 1938. A lot of Western supplies delivered to the Nationalists disappeared because of corrupt officials, while the standard of living for most people was at the subsistence level. The main concern of most Chinese living in Nationalist China at that point was day-to-day survival, and the army was left weak and depleted, though after the war it was assisted by a Japanese advisory mission.

While the Nationalists gradually lost much of their strength fighting large offensives against the Japanese that led to massive casualties, the Chinese Communist Party, from its base in the remote mountainous region of northwestern China, was the only group that attempted to address the economic conditions of the ordinary people that been neglected for decades. This effort included a program of land and agricultural reform, leading to steadily growing support for the Communists in much of rural China. Because of the rising popularity of the Communists, it allowed the Chinese Red Army to wage a successful guerrilla war against the Japanese for years, with much of Japanese-occupied China being in reality controlled by the insurgents, outside of the major cities and railways. Meanwhile the Nationalists became unpopular due to their regime's increasing corruption and the pillaging of civilians by Nationalist troops who themselves were not receiving enough supplies of food. As the war ended, Chiang rejected the advice of his Western allies and the new Japanese advisory mission to try to create some kind of unity government with the Communists, instead being determined to exterminate them. Japan's China Expeditionary Army began demobilizing its troops, who returned home, and was reduced in size from over 1 million at its peak to around 300,000. They assisted in maintaining security and order in some coastal areas and major cities, but the Chinese Nationalist Army would carry out the anti-communist campaign on its own. As the Japanese withdrew the Communists seized control of large portions of north China with their Red Army partisans that they had been raising since the start of the Japanese occupation.

Communist insurgency

Renewed offensives

Communist victory

Aftermath

Political fallout

Foreign involvement

Japanese involvement

Atrocities

Reasons for communist victory

See also

- Start-class articles

- Altverse II

- Chinese Civil War

- Revolutions in China

- Wars involving China

- Post-war period

- Revolution-based civil wars

- Communism-based civil wars

- Aftermath of the Great War

- 20th-century conflicts

- Wars involving the Republic of China (1912–1949)

- Wars involving the People's Republic of China

- 1930s conflicts

- 1940s conflicts