Romania

Kingdom of Romania Regatul României | |

|---|---|

|

Motto: Nihil Sine Deo (Nothing Without God) | |

|

Anthem: Trăiască Regele (Long Live The King) | |

Location of Romania in Europe | |

| Capital and largest city | Bucharest |

| Official languages | Romanian |

| Recognised regional languages | Hungarian, German, Ukrainian, Turkish, Yiddish, Romani, Serbian |

| Ethnic groups | Romanians, Hungarians, Germans, Ukrainians, Bulgarians, Turks, Jews, Tatars |

| Religion | Orthodoxy, Roman Catholicism, Greek Catholicism, Lutheranism, Calvinism, Orthodox Judaism, Hanafi Sunni Islam |

| Demonym(s) | Romanian |

| Government | Constitutional monarchy |

| Michael I | |

| Gábor-Tibor Martonyi | |

| Legislature | Romanian Parliament |

| Senate | |

| Chamber of Deputies | |

| History | |

• First Romanian polities | 1247 |

• Common rule under Michael the Brave | 1600 |

• Creation of the United Principalities | 24 January 1859 |

• Independence from the Ottoman Empire | 9 May 1877 |

• Unification with Transylvania | 1 December 1918 |

| Population | |

• Estimate | TBD |

| GDP (PPP) | estimate |

• Total | TBD |

| GDP (nominal) | estimate |

• Total | TBD |

| Currency | Romanian Leu (ROL) |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (Eastern European Time) |

• Summer (DST) | UTC+3 |

| Date format | dd/mm/yyyy (AD) |

| Driving side | right |

| ISO 3166 code | ROU |

| Internet TLD | .ro |

Romania, officially the Kingdom of Romania (Romanian: Regatul României), is a country in Southeastern Europe. It is bordered by Poland to the north, Russia to the northeast, Bulgaria to the south, Serbia to the southwest, and Hungary and Slovakia in the northwest. Its capital is in Bucharest, the country's largest city and main cultural and commercial centre. Other major urban areas include Chișinău, Constanța, Iași, Cluj, Cernăuți and Timișoara.

The Danube, Europe's second-longest river, rises in Germany's Black Forest and flows in a generally southeasterly direction for 2,857 km (1,775 mi), coursing through eight countries before emptying into Romania's Danube Delta. The Carpathian Mountains, which cross Romania from the north to the southwest, include Moldoveanu Peak, at an altitude of 2,544 m (8,346 ft).

Modern Romania was formed in 1859 through a personal union of the Danubian Principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia. The new state, officially named Romania since 1866, gained independence from the Ottoman Empire in 1877. Following the collapse of Austria-Hungary and Russia, the Banat, Bukovina, Bessarabia, Transylvania as well as parts of Crișana, and Maramureș became part of the sovereign Kingdom of Romania. After the dictatorship of Charles II of Romania and the successes of Romania in the Great War, Charles II was removed from office in 1947 by his son Michael I of Romania. After that, Romania had an economic boom, becoming an industrial powerhouse in Europe, and became a founding member of the European Community in 1968.

Romania is a constitutional monarchy with elements of a presidential and parliamentary system. The King of the Romanians is the head of state, sacred and inviolable, being the head of the executive branch and the commander-in-chief of the Romanian Armed Forces. The king has considerable political powers and participates in state affairs, but often refrains from doing so unless the other branches of government cannot reach an agreement or refuse to address an issue. The king also nominates the Prime Minister of Romania, and both are responsible to the elected parliament. The Romanian parliament consists of the Chamber of Deputies as the lower house and the Senate as the upper house.

Romania has been an European centre of art, science, literature, industry and cinema. It hosts several World Heritage Sites and is the leading tourist destination, receiving over ? million foreign visitors in 2018. Romania is a developed country with the world's TBD-largest economy by nominal GDP, and the TBD-largest by PPP. It is a member of the League of Nations, the European Community, the World Bank, and the IMF.

Etymology

Romania derives from the Latin romanus, meaning "citizen of Rome". The first known use of the appellation was attested to in the 16th century by Italian humanists travelling in Transylvania, Moldavia, and Wallachia.

The oldest known surviving document written in Romanian, a 1521 letter known as the "Letter of Neacșu from Câmpulung", is notable for including the first documented occurrence of the country's name: Wallachia is mentioned as Țeara Rumânească (old spelling for "The Romanian Land"; țeara from the Latin terra, "land"; current spelling: Țara Românească).

Two spelling forms: român and rumân were used interchangeably until sociolinguistic developments in the late 17th century led to semantic differentiation of the two forms: rumân came to mean "bondsman", while român retained the original ethnolinguistic meaning. After the abolition of serfdom in 1746, the word rumân gradually fell out of use and the spelling stabilised to the form român. Tudor Vladimirescu, a revolutionary leader of the early 19th century, used the term Rumânia to refer exclusively to the principality of Wallachia.

The use of the name Romania to refer to the common homeland of all Romanians—its modern-day meaning—was first documented in the early 19th century.

In English, the name of the country was formerly spelt Rumania or Roumania. Romania became the predominant spelling around 1975. Romania is also the official English-language spelling used by the Romanian government. A handful of other languages (including Italian, Hungarian, Portuguese, and Norwegian) have also switched to "o" like English, but most languages continue to prefer forms with u, e.g. French Roumanie, German and Swedish Rumänien, Spanish Rumania (the archaic form Rumanía is still in use in Spain), Polish Rumunia, Russian Румыния (Rumyniya), and Japanese ルーマニア (Rūmania).

History

Prehistory

Human remains found in Peștera cu Oase ("Cave with Bones"), radiocarbon dated as being from circa 40,000 years ago, represent the oldest known Homo sapiens in Europe. Neolithic techniques and agriculture spread after the arrival of a mixed group of people from Thessaly in the 6th millennium BC. Excavations near a salt spring at Lunca yielded the earliest evidence for salt exploitation in Europe; here salt production began between 5th millennium BC and 4th BC. The first permanent settlements also appeared in the Neolithic. Some of them developed into "proto-cities", which were larger than 320 hectares (800 acres). The Cucuteni–Trypillia culture - the best known archaeological culture of Old Europe - flourished in Muntenia, southeastern Transylvania and northeastern Moldavia in the 3rd millennium BC. The first fortified settlements appeared around 1800 BC, showing the militant character of Bronze Age societies.

Antiquity

Greek colonies established on the Black Sea coast in the 7th century BC became important centres of commerce with the local tribes. Among the native peoples, Herodotus listed the Getae of the Lower Danube region, the Agathyrsi of Transylvania and the Syginnae of the plains along the river Tisza at the beginning of the 5th century BC. Centuries later, Strabo associated the Getae with the Dacians who dominated the lands along the southern Carpathian Mountains in the 1st century BC. Burebista was the first Dacian ruler to unite the local tribes. He also conquered the Greek colonies in Dobruja and the neighbouring peoples as far as the Middle Danube and the Balkan Mountains between around 55 and 44 BC. After Burebista was murdered in 44 BC, his empire collapsed.

The Romans reached Dacia during Burebista's reign and conquered Dobruja in 46 AD. Dacia was again united under Decebalus around 85 AD. He resisted the Romans for decades, but the Roman army defeated his troops in 106 AD. Emperor Trajan transformed the Banat, Oltenia and the greater part of Transylvania into the new Roman province of Dacia, but Dacian, Germanic and Sarmatian tribes continued to dominate the lands along the Roman frontiers. The Romans pursued an organised colonisation policy, and the provincials enjoyed a long period of peace and prosperity in the 2nd century. Scholars accepting the Daco-Roman continuity theory - one of the main theories about the origin of the Romanians - say that the cohabitation of the native Dacians and the Roman colonists in Roman Dacia was the first phase of the Romanians' ethnogenesis.

The Carpians, Goths and other neighbouring tribes made regular raids against Dacia from the 210s. The Romans could not resist, and Emperor Aurelian ordered the evacuation of the province Dacia Trajana in 271. Scholars supporting the continuity theory are convinced that most Latin-speaking commoners stayed behind when the army and civil administration was withdrawn. The Romans did not abandon their fortresses along the northern banks of the Lower Danube for decades, and Dobruja (known as Scythia Minor) remained an integral part of the Roman Empire until the early 7th century.

Middle Ages

The Goths were expanding towards the Lower Danube from the 230s, forcing the native peoples to flee to the Roman Empire or to accept their suzerainty. The Goths' rule ended abruptly when the Huns invaded their territory in 376, causing new waves of migrations. The Huns forced the remnants of the local population into submission, but their empire collapsed in 454. The Gepids took possession of the former Dacia province. The nomadic Avars defeated the Gepids and established a powerful empire around 570. The Bulgars, who also came from the Eurasian steppes, occupied the Lower Danube region in 680.

Place names that are of Slavic origin abound in Romania, indicating that a significant Slavic-speaking population used to live in the territory. The first Slavic groups settled in Moldavia and Wallachia in the 6th century, in Transylvania around 600. After the Avar Khaganate collapsed in the 790s, Bulgaria became the dominant power of the region, occupying lands as far as the river Tisa. The Council of Preslav declared Old Church Slavonic the language of liturgy in the First Bulgarian Empire in 893. The Romanians also adopted Old Church Slavonic as their liturgical language.

The Magyars (or Hungarians) took control of the steppes north of the Lower Danube in the 830s, but the Bulgarians and the Pechenegs jointly forced them to abandon this region for the lowlands along the Middle Danube around 894. Centuries later, the Gesta Hungarorum wrote of the invading Magyars' wars against three dukes - Glad, Menumorut and the Vlach Gelou - for the Banat, Crișana and Transylvania. The Gesta also listed many peoples—Slavs, Bulgarians, Vlachs, Khazars, and Székelys - inhabiting the same regions. The reliability of the Gesta is debated. Some scholars regard it as a basically accurate account, others describe it as a literary work filled with invented details. The Pechenegs seized the lowlands abandoned by the Hungarians to the east of the Carpathians.

Byzantine missionaries proselytised in the lands east of the Tisa from the 940s and Byzantine troops occupied Dobruja in the 970s. The first king of Hungary, Stephen I, who supported Western European missionaries, defeated the local chieftains and established Roman Catholic bishoprics (office of a bishop) in Transylvania and the Banat in the early 11th century. Significant Pecheneg groups fled to the Byzantine Empire in the 1040s; the Oghuz Turks followed them, and the nomadic Cumans became the dominant power of the steppes in the 1060s. Cooperation between the Cumans and the Vlachs against the Byzantine Empire is well documented from the end of the 11th century. Scholars who reject the Daco-Roman continuity theory say that the first Vlach groups left their Balkan homeland for the mountain pastures of the eastern and southern Carpathians in the 11th century, establishing the Romanians' presence in the lands to the north of the Lower Danube.

Exposed to nomadic incursions, Transylvania developed into an important border province of the Kingdom of Hungary. The Székelys—a community of free warriors—settled in central Transylvania around 1100 and moved to the easternmost regions around 1200. Colonists from the Holy Roman Empire - the Transylvanian Saxons' ancestors - came to the province in the 1150s. A high-ranking royal official, styled voivode, ruled the Transylvanian counties from the 1170s, but the Székely and Saxon seats (or districts) were not subject to the voivodes' authority. Royal charters wrote of the "Vlachs' land" in southern Transylvania in the early 13th century, indicating the existence of autonomous Romanian communities. Papal correspondence mentions the activities of Orthodox prelates among the Romanians in Muntenia in the 1230s.

The Mongols destroyed large territories during their invasion of Eastern and Central Europe in 1241 and 1242. The Mongols' Golden Horde emerged as the dominant power of Eastern Europe, but Béla IV of Hungary's land grant to the Knights Hospitallers in Oltenia and Muntenia shows that the local Vlach rulers were subject to the king's authority in 1247. Basarab I of Wallachia united the Romanian polities between the southern Carpathians and the Lower Danube in the 1310s. He defeated the Hungarian royal army in the Battle of Posada and secured the independence of Wallachia in 1330. The second Romanian principality, Moldavia, achieved full autonomy during the reign of Bogdan I around 1360. A local dynasty ruled the Despotate of Dobruja in the second half of the 14th century, but the Ottoman Empire took possession of the territory after 1388.

Princes Mircea I and Vlad III of Wallachia, and Stephen III of Moldavia defended their countries' independence against the Ottomans. Most Wallachian and Moldavian princes paid a regular tribute to the Ottoman sultans from 1417 and 1456, respectively. A military commander of Romanian origin, John Hunyadi, organised the defence of the Kingdom of Hungary until his death in 1456. Increasing taxes outraged the Transylvanian peasants, and they rose up in an open rebellion in 1437, but the Hungarian nobles and the heads of the Saxon and Székely communities jointly suppressed their revolt. The formal alliance of the Hungarian, Saxon, and Székely leaders, known as the Union of the Three Nations, became an important element of the self-government of Transylvania. The Orthodox Romanian knezes ("chiefs") were excluded from the Union.

Early Modern Times and national awakening

The Kingdom of Hungary collapsed, and the Ottomans occupied parts of the Banat and Crișana in 1541. Transylvania and Maramureș, along with the rest of the Banat and Crișana developed into a new state under Ottoman suzerainty, the Principality of Transylvania. Reformation spread and four denominations - Calvinism, Lutheranism, Unitarianism, and Roman Catholicism - were officially acknowledged in 1568. The Romanians' Orthodox faith remained only tolerated, although they made up more than one-third of the population, according to 17th-century estimations.

The princes of Transylvania, Wallachia, and Moldavia joined the Holy League against the Ottoman Empire in 1594. The Wallachian prince, Michael the Brave, united the three principalities under his rule in May 1600. The neighbouring powers forced him to abdicate in September, but he became a symbol of the unification of the Romanian lands in the 19th century. Although the rulers of the three principalities continued to pay tribute to the Ottomans, the most talented princes - Gabriel Bethlen of Transylvania, Matei Basarab of Wallachia, and Vasile Lupu of Moldavia - strengthened their autonomy.

The united armies of the Holy League expelled the Ottoman troops from Central Europe between 1684 and 1699, and the Principality of Transylvania was integrated into the Habsburg Monarchy. The Habsburgs supported the Catholic clergy and persuaded the Orthodox Romanian prelates to accept the union with the Roman Catholic Church in 1699. The Church Union strengthened the Romanian intellectuals' devotion to their Roman heritage. The Orthodox Church was restored in Transylvania only after Orthodox monks stirred up revolts in 1744 and 1759. The organization of the Transylvanian Military Frontier caused further disturbances, especially among the Székelys in 1764.

Princes Dimitrie Cantemir of Moldavia and Constantin Brâncoveanu of Wallachia concluded alliances with the Habsburg Monarchy and Russia against the Ottomans, but they were dethroned in 1711 and 1714, respectively. The sultans lost confidence in the native princes and appointed Orthodox merchants from the Phanar district of Istanbul to rule Moldova and Wallachia. The Phanariot princes pursued oppressive fiscal policies and dissolved the army. The neighbouring powers took advantage of the situation: the Habsburg Monarchy annexed the northwestern part of Moldavia, or the Bukovina, in 1775, and the Russian Empire seized the eastern half of Moldavia, or Bessarabia, in 1812.

A census revealed that the Romanians were more numerous than any other ethnic group in Transylvania in 1733, but legislation continued to use contemptuous adjectives (such as "tolerated" and "admitted") when referring to them. The Uniate bishop, Inocențiu Micu-Klein who demanded recognition of the Romanians as the fourth privileged nation was forced into exile. Uniate and Orthodox clerics and laymen jointly signed a plea for the Transylvanian Romanians' emancipation in 1791, but the monarch and the local authorities refused to grant their requests.

Independence and monarchy

The Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca authorised the Russian ambassador in Istanbul to defend the autonomy of Moldavia and Wallachia (known as the Danubian Principalities) in 1774. Taking advantage of the Greek War of Independence, a Wallachian lesser nobleman, Tudor Vladimirescu, stirred up a revolt against the Ottomans in January 1821, but he was murdered in June by Phanariot Greeks. After a new Russo-Turkish War, the Treaty of Adrianople strengthened the autonomy of the Danubian Principalities in 1829, although it also acknowledged the sultan's right to confirm the election of the princes.

Mihail Kogălniceanu, Nicolae Bălcescu and other leaders of the 1848 revolutions in Moldavia and Wallachia demanded the emancipation of the peasants and the union of the two principalities, but Russian and Ottoman troops crushed their revolt. The Wallachian revolutionists were the first to adopt the blue, yellow and red tricolour as the national flag. In Transylvania, most Romanians supported the imperial government against the Hungarian revolutionaries after the Diet passed a law concerning the union of Transylvania and Hungary. Bishop Andrei Șaguna proposed the unification of the Romanians of the Habsburg Monarchy in a separate duchy, but the central government refused to change the internal borders.

The Treaty of Paris put the Danubian Principalities under the collective guardianship of the Great Powers in 1856. After special assemblies convoked in Moldavia and Wallachia urged the unification of the two principalities, the Great Powers did not prevent the election of Alexandru Ioan Cuza as their collective domnitor (or ruling prince) in January 1859. The united principalities officially adopted the name Romania on 21 February 1862. Cuza's government carried out a series of reforms, including the secularisation of the property of monasteries and agrarian reform, but a coalition of conservative and radical politicians forced him to abdicate in February 1866.

Cuza's successor, a German prince, Karl of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen (or Charles I), was elected in May. The parliament adopted the first constitution of Romania in the same year. The Great Powers acknowledged Romania's full independence at the Congress of Berlin and Charles I was crowned king in 1881. The Congress also granted the Danube Delta and Dobruja to Romania. Although Romanian scholars strove for the unification of all Romanians into a Greater Romania, the government did not openly support their irredentist projects.

The Transylvanian Romanians and Saxons wanted to maintain the separate status of Transylvania in the Habsburg Monarchy, but the Austro-Hungarian Compromise brought about the union of the province with Hungary in 1867. Ethnic Romanian politicians sharply opposed the Hungarian government's attempts to transform Hungary into a national state, especially the laws prescribing the obligatory teaching of Hungarian. Leaders of the Romanian National Party proposed the federalisation of Austria-Hungary and the Romanian intellectuals established a cultural association to promote the use of Romanian.

Establishment of Greater Romania and political instability

Fearing Russian expansionism, Romania secretly joined the Triple Alliance of Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Italy in 1883, but public opinion remained hostile to Austria-Hungary. Romania seized Southern Dobruja from Bulgaria in the Second Balkan War in 1913. German and Austrian-Hungarian diplomacy supported Bulgaria during the war, bringing about a sharp divide in the Romanian political class of the times, with the Conservative Party still trying to keep the ties with the Triple Alliance, while the National Liberal Party agitating to switch to a pro-French and pro-Russian position. The death of Charles I in 1914 of old age left Ferdinand I in charge of the country, who was eager to listen to then-Prime Minister Ion I. C. Brătianu of the National Liberal Party, but his British wife Marie of Edinburgh, as well as the fall of the Liberal government due to exposure of collusion with the French and Russian governments led to a Conservative-led government under respected politician and literary critic Titu Maiorescu.

Ultimately, the death of Austro-Hungarian Emperor Franz Joseph I and the reformatory approach of his successor Franz Ferdinand I and his Romanian advisor and newly-made Chancellor Aurel Popovici ultimately lead to a détente between the Romanian and Austrian governments, the efforts being lead by prime-minister Maiorescu. This came to fruition when, after the Second Hungarian Declaration of Independence on October 31, 1917 led to Romania entering the Austro-Hungarian Civil War on Austria's side, supporting the Army of Transylvanian Romanians under Iuliu Maniu and Alexandru Vaida-Voevod. The Romanian Army entered and marched into Hungary, getting the support of the Transylvanian Saxons, especially of the Transylvanian Lutheran Church. In the Bukovina, Romanian troops and partisans fought both against Ukrainian nationalists and Russophiles, but the Bukovina Campaign of 1918 was a quick success for the Romanian Army. The collapse of the Russian Empire into the Russian Civil War in 1918 also leads to the Sfatul Țării (English: National Council) declaring independence from the Russian Empire and then unifying with Romania.

After the Hungarian last stand at Újszőny in early 1919, Austria's weakened position and Romanian and German pressure allowed Romania to annex the Bukovina, the Banat, Transylvania, as well as parts of Crișana and Maramureș. Along with the expansion into Bessarabia, Romania had more than doubled in size and became a crucial German ally in the region. This newly-founded support for Romania, along with the British alliance to Greece led Bulgaria into further isolation in the Balkans, leading to a Bulgarian campaign into Greece, Yugoslavia and Romania at the same time, which became the Third Balkan War. Bulgaria's mobilization of almost a fifth of its male population lead to some great advances, but ultimately an alliance between the three lead to Bulgarian defeat and an armistice. Romania didn't gain any territory over Bulgaria, but Romania's new status as the hegemon of the Balkans angered Romania's southern neighbour.

After the war, Romania started industrializing, with rapid shifts to factories in the cities supplied by the raw products extracted in Romania. Particularly the Jiu Valley, a coal mining area, was booming during this time. However, problems existed even in that time, both socially and economically. The two-party system between the Conservatives and the National Liberals fell apart due to the collapse of the National Liberal Party into several smaller parties depending on the ideas, namely the Radical Liberal Party, the National People's Party and the Romanian Liberal Party. In the National Liberals' place rose parties such as minority parties for the newly-incorporated minorities, the Landonist-Syndicalist Party, inspired by the revolution of Aeneas Warren in the United Commonwealth, the Romanian Labour Party, a democratic socialist worker's party fighting for union rights, the Vlad Țepeș League, a far-right Proto-Derzhavist precursor to the Iron Guard, and especially the National Peasants' Party, a merger between the Peasants' Party and the Romanian National Party, which became the largest party in Romania. Additionally, the large landowners, both in the new and old territories, were unwilling to give up their land, and the Conservative Party's party inability to reform led to the Romanian National Party and later the National Peasants' Party gaining more and more popularity. Despite winning the 1924 elections in a landslide, the National Peasants' Party leader Iuliu Maniu was blocked by Ferdinand I from becoming Prime Minister, who instead nominated Prince Barbu Știrbey of the Romanian Liberal Party, who coalitioned with the other splinters and the Conservative Party. This led to major outrage in some parts of Transylvania, and the 1924 Cluj riots. Ethnic and religious tensions, previously kept under the tabs due to Romania's relatively homogenous population, also began flaring up, with the Hungarian and Bulgarian minorities feeling ostracized by the Romanian majority, and the Romanian Orthodox Church was now not the sole religious organization Romanians followed, with the Romanian Uniate Church being the majority church of the Romanians of Northern and Central Transylvania, as well as Maramureș.

King Ferdinand's health began deteriorating due to developing cancer, and his son and heir Charles, already known for a controversial first marriage with Zizi Lambrino which produced a child, Mircea Lambrino was caught having an affair with the half-Jewish, Roman Catholic Magda Lupescu, a scandal at the time in the predominantly Orthodox and increasingly anti-Semitic country. Due to the exposure ruining relations with Greece due to Charles's marriage to Princess Helen of Greece and Denmark, as well as Charles's rivalry with Prime Minister Barbu Știrbey, whom Charles disliked due to Știrbey's semi-public affair with Queen-Consort Marie of Edinburgh, Charles was presented with two choices: either to renounce Magda or renounce his position as heir. He chose to renounce his position as heir, abdicating it in favour of his son Michael, and moved with Lupescu to Paris under the name Carol Caragia. The same year, an Orthodox Synod awarded Metropolitan-Primate of Romania Miron Cristea the title of Patriarch, making him the first patriarch of Romania. After the collapse of the Știrbey government, Ferdinand I still refused to name Iuliu Maniu or another member of the National Peasants' Party such as Ion Mihalache or Alexandru Vaida-Voevod as Prime Minister, instead using his power to force the Conservative Party and the National Liberal splinters to create a coalition under Ion I. C. Brătianu, creating a lot of frustration with Ferdinand and the royal family, both with the snubbed National Peasants and with far-right and far-left groups. In particular, the Vlad Țepeș League founded by Octavian Goga and Alexandru C. Cuza, began gaining popularity amongst the intelligentsia and the peasant population of Romania. However, Goga's departure and rejoining of the Conservative Party under the new right-wing direction of Nicolae Iorga left the League in shambles. The only thing keeping the party together was its rising star, Corneliu Zelea Codreanu, but he began quarreling with Cuza over the direction of the party, particularly about the need of a paramilitary party wing. After an incident between League agitators and the Iași police, Codreanu assassinated police chief Constantin Manciu, and after a publicized trial, he was acquitted of all charges by a jury and then founded the Legion of the Archangel Michael, better known as the Iron Guard. Afterwards, the members of the Vlad Țepeș League who did not join the Iron Guard folded back into the Conservative Party, with Cuza reluctantly retiring from politics.

The fragile political stability that Romania achieved crumbled very quickly after the death of Ferdinand I on July 20th, 1927 from intestinal cancer, just after the return of Queen-Consort Marie from a visit to Sierra, leading to the accession of Michael, the son of Charles, as King of the Romanians. Immediately, a regency council consisting of Patriarch Miron Cristea, President of the High Court of Cassation and Justice Gheorghe Buzdugan and the King's own uncle, Prince Nicholas. The regency council notably excluded the widowed queen, who didn't want to be involved in politics directly anymore. Despite this, Marie would be offered a position on the regency council several times, each time refusing them. The unpopularity of the regency was balanced out by the stable government, until Prime Minister Brătianu developed laringytis, which would lead to his death on November 27th, 1927. His successor and brother, Vintilă Brătianu, was unable to keep the coalition between the Conservatives and the Liberal splinter parties stable, and the government was dissolved by the regency on January 4th, 1928. Deciding to wait until the elections passed through in late 1928, the regency appointed Patriarch Miron as the caretaker Prime Minister, forming a government of national unity. This move was controversial enough as is to provoke strikes, as many thought that the National Peasants' Party should finally come to power after being snubbed for so long, and the Iron Guard and the Landonist-Syndicalist Party began organizing in power and heading protests, leading to the Silistra riots and the Reșița general strike, respectively.

The 1928 general election only confirmed popular sentiment: the Liberal splinters either merged with the Conservative Party or lost their seats in parliament, the Conservative Party itself had bad results but overall better than the 1924 low, the Landonist-Syndicalist Party's ally the Romanian Labour Party, as well as the Iron Guard's political arm, the All for the Fatherland Party, made major gains. However, the clear winner, by 61.3% percent of the vote, was the National Peasants' Party under the leadership of Iuliu Maniu and Ion Mihalache. The regency, unable to oppose the National Peasants, and with the Conservatives having no coalition partner to work with, Maniu became Prime Minister. His leadership brought comprehensive land reform, a more equal taxation rate, and through a deal with the Romanian Labour Party, expanded the welfare state. This however, starting exposing rifts within the party, as the right-wing of the National Peasants under Alexandru Vaida-Voevod began openly expousing anti-Semitic and nationalistic sentiments, while the moderate wing led by Iuliu Maniu respected minority rights and worked together with Romanian Labour, including their leader, Hannah Rabinsohn. Maniu additionally pushed through women's suffrage, extended more rights to minorities in Romania and extended full citizenship to the sizeable Jewish minority in Romania. This however, brought the ire of the Iron Guard and its leader, Zelea Codreanu. On December 15th 1931, the Iron Guard began attacking several Jewish shops and attempted to burn down the Great Synagogue of Iași. This led to deputy Prime Minister Ion Mihalache travelling to Iași to get the Iron Guard to stand down diplomatically. There, he was assassinated by Legionnaire enforcer Ion I. Moța. This was an especially devastating blow to the National Peasants, as the internal lines began to show, and Mihalache was the central pillar of the party keeping the wings together. With a schism seeming inevitable within the National Peasants and with violence continuing in Iași and other parts of Moldavia and Bessarabia, the regency council used the Royal Prerogative and dismissed the Maniu government, installing a caretaker Conservative government under world-famous historian and literary critic Nicolae Iorga, whose first move was to outlaw the Iron Guard and the Landonist-Syndicalist Parry, and arrest the main conspirators behing the Iași pogrom. However, a court in the opposite end of the country found the Legionnaires innocent, claiming the shooting was an accident, and that the rioting was an act of self-defence, showing the growing popularity of the Iron Guard within Romanian society.

Great Recession, Carlist Dictatorship and Legionary Terror

The Iorga caretaker government, while led by a popular leader, had angered many people during its short tenure. The outlawing of both the Iron Guard and the Landonist-Syndicalist Party led to uprisings and anger within Romania, most of which were able to be suppressed easily within Romania. Zelea Codreanu once again stood trial, and he was once again declared innocent by a jury, to the ire of Iorga and the regency. The Landonist-Syndicalists, now radicalized, began a strike in the industrial city of Ploiești, which was quickly suppressed, with the heads of the Landonist-Syndicalist Party, Gheorghe Cristescu, Elek Köblos and Vitali Holostenko, arrested and later executed at Jilava. However, the effects of the Great Recession of 1931 started already being felt throughout the country, and it led to more economic chaos. The Iorga government's scramble to reduce the size of the welfare state, as well as their blocking of union rights began to grow resentment towards Romania's now-impoverished population. In the Jiu Valley, coal miners under the leadership of the Jiu Valley Coal Miner's Union, a moderate union which worked with the National Peasants' Party in the past, went on strike against the removal of union rights, which was clamped down brutally by the government. The brutality of these actions, written down by the Panait Istrati, further destroyed public faith in the Iorga cabinet. Despite this, the regency voted to keep the Iorga government until the 1932 elections.

The regency's obvious bias towards the Conservative Party led to National Peasant leaders Iuliu Maniu and Alexandru Vaida-Voevod, brought together by their opposition to the Conservative Party, beginning secret talks with Prince Charles, who already had planned a return to Romania. Organizing a flight from Berlin, where he was residing, Charles II was greeted with enthusiasm and relief by the populace, who felt the regency was failing massively. Charles initially became an advisor to the regency, but quickly, after convincing both Patriarch Miron Cristea and his brother Prince Nicholas, the regency abolished the law removing Charles from the line of succession and Charles was crowned Charles II of Romania on November 30 1932, with his now-wife Magda Lupescu becoming Queen-Consort. His son, Prince Michael, was granted the title of Grand Voivode of Alba Iulia, a title still used by the heir-apparent to this day. The National Peasants won the elections with slightly reduced margins, and Maniu became Prime Minister once again, but clashes with Charles led to his removal and the swearing-in of Vaida-Voevod as Prime Minister. However, his more conservative policies led to his expulsion from the party in 1934, leading to a leadership crisis. However, with a large wing of conservative National Peasants leaving the party and joining the Conservative Party, Iorga became once again Prime Minister after the fall of the first Vaida-Voevod administration. Now having a slight majority in the Romanian Parliament, Iorga was able to push through rollbacks on Maniu's reforms, limiting the rights of workers and rolling back welfare protections in favour of a protectionist approach to the Romanian economy. His rejection of modernism and embrace of cultural conservatism brought him closer to the Iron Guard in some areas, but it is unclear if Iorga and Zelea Codreanu ever met. The Iorga cabinet's rollback on protections and attack on the Landonist-Syndicalist Party led to more worker strikes in major industrial towns such as Reșița, Ploiești, Hunedoara, Brașov and Călan in 1935. Iorga's crackdown of these uprisings, as well as the help the illegal Iron Guard gave to local authorities and the tacit support given to these crackdowns by the King, led to a young member of the Landonist-Syndicalist Party, Nicolae Ceaușescu, fatally shooting Iorga at the inauguration of a factory in Bucharest. Iorga survived the attack itself, but died two weeks later of the wound. King Charles immediately appointed Patriarch Miron Cristea as caretaker Prime Minister, a position which Cristea held until his death. Charles's aspirations for absolute power, as well as his jealousy over Corneliu Zelea Codreanu's massive popularity within the Romanian populace, led to further crackdowns on both the Iron Guard and the Landonist-Syndicalist Party. Considering the time had come for national unity within Romania, Charles drafted a new constitution which gave him nearly-absolute power and abolished the party system, making many of them illegal. The Conservatives under the new leadership of Octavian Goga, reformed themselves into the National Renaissance Front, which became the sole legal party within Romania. All parliament members refusing to join this new front were forced to resign and were put under surveillance by the Garda Națională, the new secret police instituted by Charles II.

After Miron Cristea's death, Corneliu Zelea Codreanu began a march on Bucharest, trying to demand the position of Prime Minister for himself and his party. This march was broken by the Romanian Army, which led to the Iron Guard's transformation into a terrorist organization striking much terror within Romania. Attacks on Uniate churches and clergy, burnings of synagogues, and clashes with other ethnic militant groups, such as the Internal Dobrujan Revolutionary Organisation, a Bulgarian terrorist group. The National Renaissance government under Prime Minister Armand Călinescu tried to contain the influence of the Iron Guard, but ultimately failed, with Călinescu being assassinated by the Iron Guard in Vaslui, and his successor Alexandru Vaida-Voevod severely wounded in a train bombing between Sinaia and Bucharest. Vaida-Voevod's successor was Octavian Goga, who began to resent Charles II's overbearing nature and his sidelining, and planned a coup with Corneliu Zelea Codreanu to install his son Michael I as a puppet king. This plan fell apart, however, after Goga's secretary betrayed him, which led to Goga's arrest, imprisonment and eventual execution. Charles II's next pick was former Liberal Gheorghe Tăttărescu, who managed to capture important Iron Guard leaders, and made a deal with the national minorities, particularly the Turks and the Jews, leading to stronger unity against the Iron Guard. Tăttărescu master-minded the capture of Zelea Codreanu in his native Huși. Charles II, wanting a smooth but swift trial, appointed long-time friend Ernest Urdăreanu as Prime Minister in a cabinet shuffle. The trial took several months, but ended in the death of Codreanu by hanging. Several Iron Guard factions, including one under Horia Sima and Ion I. Moța, fought back, but were defeated, with only a few under Sima and Moța fleeing into exile in Russia. With Charles's power now fully secure, he began ruling the country with an iron fist, and instituted a powerful cult of personality. After the suspicious death of Patriarch Nicodim Munteanu, the new Patriarch Iustinian Marina became a close ally of Charles II, who sought to rally the former ultra-Orthodox base of the Iron Guard. Together, they planned to do this by reuniting the Greek Catholic Church of Romania with the Romanian Orthodox Church, as well as with the outlawing of several Neo-Protestant groups, such as the Tudorites, the Seventh-day Adventists, the Jehovah's Witnesses and the Old Calendarists. The appointment of Carlist loyalist Alexandru Vaida-Voevod, who was born in a Greek-Catholic family, but converted to Orthodoxy at the behest of Charles, was supposed to make the transition easier. Despite many protests, both domestically and internationally, including from both papacies, the forced unification of the churches was decreed, and dissident Uniate clergy and faithful were put either under house arrest or imprisoned, including Primate and Metropolitan of Alba Iulia and Făgăraș Alexandru Nicolescu, who died due to his poor health and stress at the Orthodox skete at Dragoslavele. While the move was popular within Iron Guard-popular areas such as Dobrogea, Moldova and Bucovina, it had less of an effect in other areas of the country, and a large contingent of former Peasantists in the National Renaissance Front who refused the unification with the Romanian Orthodox Church left the Front, leaving Charkes's rule popular with the masses in the Old Kingdom and Bucovina, but deeply unpopular with parts of the political class and in Transylvania.

March Crisis and the Great War

During a speech at the funeral of National Renaissance Front member Richard Franasovici on February 24th, 1942 in the Bellu Cemetery in Bucharest, Charles II was almost assassinated by Lajos Csupor, a Hungarian Landonist who tried to take out Charles II at the behest, as was later revealed, of the exiled leader of the Landonist-Syndicalists, Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej. As Csupor made his way through the crowd, he was spotted by some members of the funeral procession who began shouting and fleeing, and as Csupor made his shot, the King's best friend and former Prime Minister Ernest Urdăreanu jumped in front of Charles, sacrificing his own life for his monarch's. After Csupor's arrest, he was questioned and tortured by the Garda Națională, where he revealed the involvement of the exiled Landonist-Syndicalist leadership in Italy. However, worsening tensions with all of Romania's neighbours besides Poland had led Charles to believe that a conspiracy made by the Russians or one of their allies would try to remove him from power. He dismissed the report made by the Garda Națională as a lie and ordered more interrogation until he would reveal whether he was hired by the government of Hungary. After more torture, Csupor admitted falsely to the charge and was executed by hanging for this.

The accusation that Hungary tried to kill the monarch of Romania led to a diplomatic crisis between Romania and Hungary. Csupor's forced confession was published in several Romanian and international newspapers, which led to Hungary's government under Miklós Horthy to deny these accusations. Charles II instituted an emergency cabinet meeting at Cotroceni Palace on March 1st, where he ordered a cabinet reshuffle. There, Charles appointed famous general Ion Antonescu as Prime Minister under war circumstances, and planned to give Vaida-Voevod the position as Minister of Agriculture. However, the Minister of Foreign Affairs, Grigore Filipescu, objected, saying that the Hungarian government's claims were genuine and that the second confession by Csupor was false. For this, Filipescu was arrested and Vaida-Voevod became Minister of Internal Affairs, while the Minister of Internal Affairs, Prince Michel Sturdza, became the Minister of Foreign Affairs. The removal of Filipescu, considered a voice of reason within the National Renaissance Front, and the appointment of loyalist Michel Sturdza as Minister of Foreign Affairs signalled to Hungary and Russia that Romania was preparing for war. As Romania started mobilizing its army, Horthy telegraphed Russian leader Alexander Kolchak, begging it to honour the alliance treaty Hungary and Russia signed in 1935. Eventually, Hungary begged Romania to accept reparations for the attack in order to prevent war, but these pleas fell on deaf ears, and it ultimately came to war.

On March 16th 1932, the Romanian government declared war on Hungary, and with its troops mobilized, invaded Hungary on March 17th, with the First and Second Romanian armies marching quickly and taking Debrecen, while the Third and Fourth Romanian armies took Szeged, on the Romanian border, just as quickly. With the outbreak of war and with two of Hungary's major cities taken very quickly, the Russian foreign minister, Count Vladimir Kokovtsov, sent an ultimatum to the Romanian government, demanding that Romania cease its hostility and withdraw all troops from Hungary. Sturdza refused the offer and began to pressure Germany, whom Romania was allied to, to intervene in this situation. German foreign minister Konstantin von Neurath confirmed diplomatic support for Romania, but did not affirm German military support. With Romania unwilling to stop its campaign in Hungary, Russia began to mobilize its troops to attack Romania, which action escalated the conflict to a point where Germany declared on Russia on March 24th. This all culminated into the declaration of war on France on April 1st, which is considered one of the starting dates of Great War I.

Romanian advances into Hungary turned into a stalemate after the surprise takings of both Szeged and Debrecen, While the Romanian Second Army managed to take Nyíregyháza on March 20th, the First and Second Armies were stuck on the Tisza River, unable to cross it due to the set-up Hungarian defences, but with the loss of Szeged, the Romanians had a clear path to cross the Tisza river. Thus, the bulk of Hungarian soldiers were sent either into diversionary assaults towards Giula and Oradea Mare or into the Horthy Line, a line of defences running from the Tisza at Csóngrad to the Yugoslav border, built to counteract the weakness of Szeged in case of a breach of the Tisza river, itself a natural barrier. Unable to overcome the Horthy Line's defences, the Romanian Fourth Army massed opposite the town of Csóngrad, trying to take it, starting the Battle of Csóngrad, the bloodiest battle in the Romanian-Hungarian War. This battle was ultimately a meatgrinder of troops, and quickly dissolved into shelling on both sides of the river. The attack on Csóngrad however was quickly threatened by the unforeseen entry of Yugoslavia into the war, who invaded the southern Banat, taking the strategically important Panciova and threatening to take the city of Becicherecu Mare. The Romanian leadership under Charles II and Marshal Antonescu scrambled to take whatever bits of the Third, Second and First armies they could spare for the offensive, refusing to touch the Fifth, Sixth and Seventh Armies, stationed in Bessarabia and the Bukovina, prepared for a Russian invasion, with additional recruitment also being undertaken to bolster the Romanian war in the west. However, this led to a Hungarian First Army counterattack, which led to the Second Army's positions being overrun, and the Hungarian troops were 25 km away from Debrecen when the Romanian counterattack by the First Army could drive the Hungarians back over the Tisza. However, the intervention of Austria, the Czech Republic and Germany led to the strategic retreat across the Tisza for Hungarian troops.

Russian troops invaded the Bukovina and Bessarabia on April 16th, 1942. With resistance being limited, the Russian troops managed to take Chisinău after a week of fighting, and by the end of April, Romania had lost the entirety of Bessarabia and the Bukovina, as well as a large part of Moldavia. With the loss of many important cities such as Cernăuți, Iași, Chișinău, Galați and Ismail, the Romanian troops of the Fifth, Sixth and Seventh Armies made their first stand along the Siret River, but they were repelled and in full retreat from the Siret by mid-May. The line that ultimately held was the so-called Averescu Line, conceived as a last defence to prevent Russian armies an advance towards Bucharest. It ran across the Buzău, Siret and Danube rivers all they way from the Carpathians to the sea. The Averescu line managed to stop any Russian incursion further into Wallachia, and the Battle of Buzău was the longest battle on Romanian soil to date, lasting from August 12th to December 1st of 1942. The attempted breakthrough by the Russian Third, Fourth and Fifth armies was a total disaster. Luckily for Charles II, the war in Hungary had just wrapped up due to Czech, Austrian and German intervention, as well as with the Fall of Belgrade, leaving the First and Second Armies able to return to the East. While Bulgaria's entry into the war on June 21st panicked the state into the creation of the Eighth Army by pulling resources from the armies in Hungary, the main fighting the Bulgarians were undertaking in 1942 was in the defence of Yugoslavia as well as against Greece. Even then, fighting and battles happened in Southern Dobruja, including a raid on the port of Varna undertaken by the Romanian Navy. The Romanian Navy fought bravely in the war, with the Black Sea Fleet defeating the Russian Black Sea Navy at the Battle of Tuzla and at the Battle of Snake Island, while the Romanian Riverrine Fleet helping both keeping the Russians at bay on the Danube and defeating riverrine attempts to supply the Bulgarian troops in the Dobruja. At the same time, the timely intervention of Greece in the war prevented Turkey from aiding Bulgaria in an invasion of Romania.

1943 was the year the relief Romania needed. With the German-Polish-Czech Gorlice-Tarnów offensive of 1943 into Southern Poland, and after the liberation of Southern Poland at Stanisławów and Kołomyja, the German, Polish and Czech troops entered the occupied Romanian Bukovina, aided by the First and Second Romanian Armies who used the passes between Transylvania and Moldova itself, leading to the liberations of Suceava, Rădăuți, Storojineț and Cernăuți. In order to support the offensive, the Romanian Fifth, Sixth and Seventh Armies made their own campaign, breaking through the Russian defensives on the Buzău River, starting the Focșani-Galați campaign, which due to Russian corruption and incompetence led to a route of the Russian army beyond the Prut River, which led to the Liberation of Iași and Bacău. The campaign, led by Marshal Ion Antonescu, led to major celebration in Bucharest and renewed faith in the Romanian government during the war, and helped to reoccupy the Romanian railways of Moldova, whose losses was a major security risk. Antonescu recommended to Charles II of Romania that, now that the situation significantly improved on the front, he appoint a new Prime Minister so Antonescu could focus on the war effort. Charles II appointed popular politician Ion G. Duca, who together with Charles II was tasked with keeping relations up with its allies and to keep morale up on the home front. However, with the fortification of the Russian line on the Prut River proving too strong, the Romanian armies remained on the river, waiting for an opportunity to retake Bessarabia.

The Romanian Third and Fourth Romanian armies were involved in the front against Yugoslavia, fighting with Austria and Germany at the battles of Kragujevac, Niš and Priština. The hard campaign saw heavy losses due to the mountainous terrain and the viciousness with which both Bulgarian and Yugoslav forces fought with, which led to difficulties in advancement and supply lines being disrupted by guerilla troops. The intervention of Italy drew away a majority of Austrian forces from the Yugoslav campaign, but those were managed to be supplemented by Croatian and Bosnian volunteer batallions fighting together with the Germans and Romanians in the Balkans. Ultimately, Skopje, the provisional capital, was taken by the joint German, Czech and Romanian forces in November of 1943, with the Yugoslavia campaign called a success by January of the next year. However, with the fortifications undertaken by the Bulgarian government, no campaign into Bulgaria was possible in 1944 from Vardar. The Third Army remained as part of the Allied occupation force of Yugoslavia, unlike in Hungary, where Germany and Austria felt the Czechs and Poles should do it, due to possible riots. The Fourth Army was reassigned in the Dobruja, fighting off both the Bulgarian army and the Internal Dobrujan Revolutionary Organisation, a Bulgarian nationalist group. The Dobrujan front saw a Bulgarian spearhead and brief occupation of Bazargic being fought off by the Romanian Fourth and Eighth Armies and by local Turkish militias, who had been treated respectfully by the previous administrations, as well as an attempted assassination of Queen-Consort Magda Lupescu and Grand Voivode of Alba Iulia Michael in a visit to the town of Balcic on the coastline close to the front line by Bulgarian assassin Docho Mihaylov.

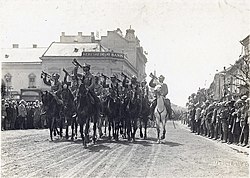

With the collapse of the Russian frontlines in August 1945, Romania was able to easily retake Bessarabia, as well as occupy the southern Ukraine up to the mouth of the Dnieper River, Romania focused a majority of their army into finally breaking Bulgaria out of the war. Due to the sudden amount of troops, as well as an internal uprising, Bulgaria became the first nation of the Entente Impériale, alongside the governments-in-exile of Hungary and Yugoslavia, to surrender to the Triple Alliance. With the front in Bulgaria secured, Romanian troops made up the plurality of the forces that finally succeeded in obtaining a surrender from Turkey. Charles II organized a large victory parade in Bucharest, and planned to send Romanian reinforcements to the west to combat France. However, Romanian troops instead were tasked with keeping the occupations clear in Bulgaria, Yugoslavia and the southern Ukraine. After the end of the war on May 25th, 1946, the Romanian army didn't demobilize immediately, but was kept on stand-by by Charles II, a move which angered his generals who thought the victory was hard-earned and that their troops needed rest, particularly the popular Ion Antonescu. While Charles II himself remained himself in the east, travelling to the occupied Ukrainian territories for inspection of the troops there accompanied by his wife Magda, while foreign minister Prince Michel Sturdza and Prime Minister Ion G. Duca attended the peace conferences in Germany. For its efforts in the war, Romania gained what felt like very little, only receiving the Timok Valley as a prize from the victory in the Balkans.

Transnistrian War and end of the Carlist regime

During Charles II and his wife's tour of the occupied Russian territories, he arrived in the city of Balta, where he met the leader of the Inochentists, Gheorghe Zgherea. He led a procession of the Romanian-speaking population of Balta and knelt before the king, proclaiming Charles the 'Saviour of all Romanianhood'. The Inochentists had been a Romanian splinter from the Russian Orthodox Church, which had been previously outlawed by the Carlist dictatorship in the aftermath of the Iron Guard's fall, led by the so-called Saint Inochenție of Balta in the late-19th century. Based in what remained Russian territory after the Russian Civil War, Inochentism had spread into Bessarabia, and after its outlawing in Romania, many adherents had fled to Balta.

Charles II, who already felt slighted by the allies' small reward after such great Romanian struggles in the first Great War, saw this action by Gheorghe Zgherea and the Romanian community of the occupied territory between the Dniester (Romanian: Nistru) and the Southern Buh (Romanian: Bugul de Sud) as a pretext to demand the territory as a bonus for its efforts in the Great War. By royal edict, he legalised the Inochentist movement in Romania again, a move which angered Patriarch Iustinian Marina, who demanded that the Iron Guard-affiliated Army of the Lord movement within the Romanian Orthodox Church be made legal as well.

Geography, environment, and climate

Government and politics

Political parties

Foreign relations

Military

Administrative divisions

Economy

Infrastructure

Tourism

Demographics

Languages

Religion

Education

Science and technology

Culture

Arts

Public holidays

Sports

Symbols

See also

| This page uses material from the Wikipedia page Romania, which is released under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License (view authors). |

- C-class articles

- Altverse II

- Romania

- Balkan countries

- Countries in Europe

- Eastern European countries

- Member states of the Council of Europe

- Member states of the European Community

- Member states of the League of Nations

- Member states of NTO

- Monarchies

- Romanian-speaking countries and territories

- Southeastern European countries

- States and territories established in 1859

- Monarchies of Europe