History of the Rätian Union (Merveilles des Morte)

| Part of a series on the |

| History of the Rätian Union |

|---|

|

Background 16th-century 17th-century 18th-century |

The Rätian Union was a country in central Germany, formed in 1534 from a union of Jungist states, including Thuringia and Saxony. The nation has its roots in the Protestant Reformation, which was begun by Konrad Jung in Thuringia in 1504, and the ideological teachings of the Thin White Duke, which after 1517 represented a sociopolitical movement in favor of Christian communalism and republicanism through "rätia", or councils. The early union expanded to include the region of Franconia in the 1530s, as part of a conflict between the successors of the Thin White Duke: Henry I, Apostolic President and Hugh the Heir, Duke of Thuringia. During the mid century the country entered into a civil war, catalyzed by the conflict between the entrenched nobility and the enfranchised lower classes, which culminated in a severe weakening of the authority of the hereditary dukes in favor of republican institutions.

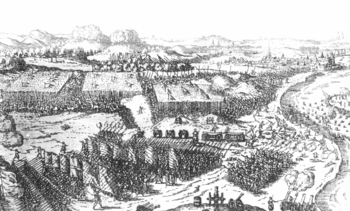

At the end of the 16th-century the Rätian Union became embroiled in the Forty Years' War, and although the Rätian side emerged victorious, the Rätian Union's territory was particularly devastated and depopulated by the conflict.

Pre-Reformation (1450s–1504)

Thin White Duke

Prior to the creation of the Rätian Union, its primary constituency Thuringia was ruled by the Thin White Duke of the House of Jenagotha, who would prove to be one of the longest serving and most influential European monarchs in history. He rose to prominence under the tenure of Henry VIII, Holy Roman Emperor, becoming the Emperor’s high steward and close advisor. He is credited with the phenomenon of Swissophobia, or the opposition to the Swiss Confederacy under the House of Lenzburg and its unusually influential dominance over German and European politics; Henry VIII from the rival Přemyslid Dynasty was keen to challenge Lenzburger hegemony, leading to the Lenzburg-Premyslid War (1484-1489).

However, this also began the Thin White Duke’s rivalry with the Papacy. The House of Lenzburg had postured themselves into one of the Papacy’s most entwined dynasties; the Papal States was in fact ruled by a Swiss pope, Innocent VII, who had sent military aid to the Swiss, and sheltered the fugitive Eberhard von Lenzburg after the Swiss defeat. This made the Thin White Duke a target of Papal retaliation, and in turn made the Thuringian skeptical of the intentions and legitimacy of the Papacy. The Thin White Duke would claim to begin receiving religious visions, which later impacted his beliefs and writings. Although the subject of his visions were initially paid no mind by the rest of the Catholic world, Innocent VII via his ally the Archbishop of Cologne would place a spotlight on the Duke and accuse him of heretical writings in an effort to discredit him, and he was excommunicated soon after in 1490.

It was around this time that the Neo-Adamite sect first rose to prominence. The Adamites claimed to have regained the primordial innocence of Adam and are said to have practiced an authentic and devout form of Christianity, which included a lack of clothing. They preached that "God dwelt in the Saints of the Last Days" and considered exclusive marriage to be a sin. The Adamites declared that the chaste were unworthy to enter the Messianic kingdom, and preached against monogamy. Although the Thin White Duke did not promote such a sect, he did nothing to combat it either, owing to his self-imposed exile after his excommunication and his hesitancy to agree with the Papacy at face value. He also credited the movement’s rise as directly correlating with the Pope’s corruption and injustice toward the Germans. Later, although publicly Catholic, the Thin White Duke partook in Adamite customs in an effort to observe and test them, something that would later be used as criticism against him. It was during this time that he first anonymously published anti-papal literature, stating, “a renewal of Christianity is needed and is coming, and that clerical corruption, the Papal despotism, and the exploitation of the poor will be stopped,” and he envisioned himself a new ruler who would emerge after the “flood” wiped out the old church.

Having gained the attention of the Papacy the Thin White Duke was ordered to combat the Neo-Adamites immediately or risk further excommunication, which he claimed publicly to be doing. Around the same time Henry VIII died of old age, and a new imperial election began. The Thin White Duke’s unpopularity over the controversy made himself or his desired candidate, Edmund Alwin of Saxony untenable, while the Thin White Duke’s grandson Henry, who was outspokenly against the actions of the heretics and his own dynasty, was considered more palatable. He sided with the inquisitors sent to Thuringia, while also attempting to negotiate a peace between all parties, gaining him much popularity. As such Henry would be elected as Henry IX and set about a mission against the Adamites.

Henrician Civil War

An inquisition emerged led by the Archbishop of Mainz and the military commander Hanns von Wulfestorff, which soon turned into an informal crusade in terms of brutality. Although against the Adamites, Henry IX objected against retaliation toward the people of Thuringia, and objected to a proposing deposing of his grandfather. For this Wulfestorff led his inquisition forces to attack the imperial capital at Frankfurt in an attempted coup, earning him the moniker “Caesar of Germany”. This sparked the Henrician Civil War, which proved particularly devastating toward the people of Thuringia. The Adamite sect was effectively wiped out, but ultimately so too was Wulfestorff’s dictatorship. By 1495 Henry IX had retaken control of the empire, and the Thin White Duke had survived.

Although the Papacy and its allies had devastated Thuringia, this would have religious repercussions across for decades to come. The brutality inflicted against Catholics and heretics alike, and the disregard for the nation’s sovereignty to disastrous effects, had radicalized many. In the aftermath as the nation attempted to rebuild and comply with Papal decrees, the clergy took up or expanded the practices of indulgences. Despite indulgences having been partially regulated since the days of the Hussites and the Ecumenical Council of Prague (1412-1414), these rules had begun to be bent in war torn regions such as Thuringia. Indulgences were sold to the desperate of the war—in favor of lost loved ones or those who had been condemned as heretics. There were churches who joined in the practice, hoping to use raised funds to fulfill their need to perform a certain amount of charity, and to meet their obligations to the Pope and their parishes alike. Others began to sell indulgences on behalf of the church, keeping half the amount raised for their own benefit.

Reformation Era (1504–1534)

A young theologian and writer at the time, Konrad Jung would become one of the most vocal opponents against the growing practice of indulgences. Additionally Jung began to formulate his own set of beliefs, and he gave a number of speeches in academic circles on the doctrine of justification, and God's act of declaring a sinner righteous, by faith alone through God's grace. In 1498 Jung created a thesis on the exploitation of the peasants and common people by powerful institutions. In 1500 he became Vicar of Saxony and Thuringia by his religious order, and he became the overseer of eleven monasteries in the region. In this post Jung would observe numerous problems or acts of corruption left over from the days of the Henrician Civil War, and he began an arduous process to try to right them.

The Reformation is usually dated to 31 January 1504 in Erfurt, Thuringia, when Konrad Jung published his 105 Theses. Having finally reached a breaking point in his attitude toward the church, Konrad Jung had decided to compile an entire list of grievances. He sent this detailed list to the Pope in Rome and several other key theologians, such as the Archbishop of Mainz. Afterward, and feeling as though he needed to get his point across, he nailed a copy of his grievances on the church door of Erfurt Cathedral. Although at the time Jung did not expect much, unknown to him this would lead to a series of changes commonly called the Reformation. Around the same time the Thin White Duke first published his own manifesto, collectively becoming the tenets of Thinwhitedukism. These two movements combined would later form the basis of the Rätian Union’s governance.

Thanks in part to the robust printing press industry established by the Thin White Duke, both works began to rapidly spread. By the end of the year these texts had flooded Thuringia and much of the Holy Roman Empire. Within two weeks, copies of the theses had spread throughout Germany; within two months, they had spread throughout Europe. These writings spurred on numerous developments. Jung’s work appealed greatly to the remnants of the Adamites, as well as the nobility most affected by the Henrician CIvil War, including several nobles in eastern Thuringia who continued to shelter the Adamites. Collectively known as the “Conspirators” and the first Jungists – Conrad von Lautertal, William of Mühlberg, William von Bibra of Meiningen, Gregor von Hanstein of Altenburg, et al – this group marched on Erfurt to compel the Thin White Duke to incorporate Jungist ideology in Thuringia. As a result he would become the first Duke to convert to the Jungist faith, and Thuringia became the heart of the Reformation. In line with Jungist teachings and his own beliefs, the Thin White Duke allowed the confiscation or secularization of church lands throughout the country.

Early Wars of Religion

A coalition of Catholic states in the Saxony region emerged to combat the spread of the Reformation, and were openly provoked into attacking the Conspirators in 1505. This would lead to the Wolfen War, which solidified an alliance of early Jungist states – namely Thuringia, Saxony, and Brandenburg – and led to the establishment of the first Jungist bishopric in Meissen. The most zealous in Thuringia (such as the previously heretical Adamites) urged the creation of a “utopia” as defined by the writings of the Thin White Duke, in which life would return to how it was in the time of the Apostles, but their goal would fail to be achieved at that time. These zealots would later form the backbone of the first Jungist military orders, and splintered into the radical anabaptist sects that influenced the later Great Peasant War.

Just as the Jungist movement was beginning, Emperor Frederick IV died unexpectedly and was succeeded by Ottokar I, ending a period of weak emperors and beginning imperial backlash against the Jungists. The Diet of Speyer under Ottokar I formally condemned Jung and his work, and the Thin White Duke was condemned for the belief that Thuringia was directly profiting off the religious conflict. Only a year later Konrad Jung would be assassinated while preaching in Thuringia, causing the Protestant movement to a turn toward radicalization and militarism that originally was against Jung’s teachings. As a result several Protestant sects would emerge, many incorporating the teachings of the Thin White Duke, and Thuringia became involved in several wars of religion across the Empire. Although he personally converted sooner, the Thin White Duke would not formally decree that Thuringia was to follow Jungism as its state religion until 1510.

The Thin White Duke disappeared from the spotlight for a time, although he sanctioned Thuringian intervention in the War of the Bavarian Succession, which also saw one of his sons Hugh the Heir rise to prominence. Religiously while Jung’s companion Johann Freud had largely taken his place, he proved to be less charismatic and active compared to his predecessor, and several reformers sought to become the new “face” of the reformation. Martin Breuer was one such figure, who wrote extensively and expanded Jung’s teachings. Breuer accepted a controversial scheme proposed by the Archbishop of Mainz, which placed a Jungist synod led by him collectively as the new “Primate of Germany”, in an effort to negotiate a reconciliation between Jungists and Catholics. In actuality this caused confusion as Breuer used his claimed position as head of German Catholics to push for Jungist reforms.

Breuer also used his authority to end the Mainzian inquisition against Jungists. Rather, he labeled some of Mainz’s teachings, their anti-Jungist works, and their church policies, as the true heresy. During this era the destruction of Catholic icons increased and the proliferation of Breuer’s texts intensified, making him the quintessential Jungist reformer. Although this caused the rate of conversion to Jungism to increase exponentially, and for the inquisition to be reversed in most places, many Catholics in the Empire resisted despite the Archbishop of Mainz’ supposed handing off of power. Numerous other Primates of Germany sprung up, such as the Archbishop of Salzburg, all claiming to be the legitimate head of Catholicism in Germany, with many of them criticizing Mainz for the “deal with the devil”. And the vast majority of Catholic churches simply continued business as usual, despite Martin Breur’s henchmen carrying out enforcement of the “correct” church doctrine. Additionally, although Martin Breuer claimed to be speaking on behalf of the Jungist movement, in actuality the religion remained very decentralized, with each community tending to do its own affairs, and it became clear the synod actually did not have authority over most, if any, of the numerous churches across the Jungist movement.

Great Peasants’ War

By the time of Jung’s death many of his works had not yet been completed, and his early message regarding injustice appealed greatly to peasants held under serfdom. Combined with the teachings of the Thin White Duke, as well as the reformer Benedikt Nietzche, this became an unstable situation. Nietzche was from the lower classes himself and he extrapolated from the Duke and from Jung a belief in the introduction of further political and legal rights for the lower classes. He called for religious communalism and the end to wealth inequality and feudalism, and religiously was against infant baptism in favor of adult (re)baptism, later known as anabaptism. These ideals influenced the outbreak of a peasant uprising in central Germany in 1515, which later spread across the Empire. Within a year tens of thousands of peasants had revolted creating an Empire-wide crisis known as the Great Peasants’ War.

In Thuringia the peasantry and nobility fought extensively, however, the Thin White Duke saw the revolt as an opportunity to compromise and create an implementation of his socio-religious belief system. Although the Thin White Duke agreed in equal and communal living, he argued the necessary doctrine of the “vanguard party” for the purpose of managing the distribution of wealth and guiding of the nation toward the utopia. The Duke’s strategy was to negotiate for said vanguard to primarily be the nobility, at least those loyal to such ideals, and thus the peasants managed to negotiate their will while not completely usurping the entire feudal system. They would sign the Twelve Articles, an arrangement that granted the peasants of Thuringia several inalienable rights, as well as military support, in exchange for the recognition of the Thin White Duke as ruler and his proposed governmental structure. The Twelve Articles would later be praised as one of the founding documents for the Rätian Union.

With Thuringian support the peasant army was a force to be reckoned with, and would not be completely defeated by the powers of the Holy Roman Empire. Instead an uneasy peace emerged, forcing the most powerful states of the Empire to recognize the partial success of the revolt in places such as Thuringia, and the implementation of radical political theory. Nietzche, at the head of the formalized army became one of the first elected leaders of the new nation, and one of the key “Apostles”, along with other nobles, reformers, and Jenagotha dynasts. The Thin White Duke’s scheme was not universally accepted however, and in late 1516 a counter revolt emerged among conservative nobles of Thuringia with support from foreign powers such as Bohemia. After the 1517 Battle of Apolda the Thin White Duke would be victorious, crushing the old Thuringian nobility and defending the fledgling new nation.

Establishment and “Old Government”

In 1517, following the victory of the Apostles at Apolda, a meeting was held in Erfurt which created the Supreme Rätia of Thuringia. This would mark the beginning of Thinwhitedukism’s implementation and the creation of the Jungist Räterepublic of Thuringia (JRR of Thuringia), which later would be the foundation of the Rätian Union. A new law system was created which included basic human rights and privileges based on the Twelve Articles, and Nietzche was selected as the first elected president of the nation. In accordance with the Duke’s vision, Thuringia became divided into a series of local rätia, which were subordinate to the supreme assembly in Erfurt. The brutal civil war allowed numerous fiefdoms in Thuringia to be replaced or dissolved; the nobility of Thuringia would be forced to reckon with these new developments, although they were also placated by the careful balancing act that ensured the nobility was still almost always above the lower classes.

The next five years, known as the “Thin White Duke Era” or more commonly the “Old Government”, would be characterized by near constant defense of the rätian system against foreign and domestic threats alike. The Founding Fathers of the nation – the Thin White Duke, Nietzche, first President of the Magi Sebastian Gauck – ruled personally and harshly in a quasi-dictatorship at times to deal with emergencies. Although each man was idealistic and loyal to the concepts of their “revolution”, they found themselves compromising their vision in the name of the fledgling nation’s survival. Thuringian forces would directly intervene in neighboring nations in an effort to spread their beliefs abroad. First in Hesse a loose Jungist republic was declared, however, Hesse preserved its aristocracy and refused to cooperate with Thuringia’s utopian vision, in what would eventually become nicknamed as the Thuringian-Hessian Split. Elsewhere Saxony also fell under Thuringian influence, and was more accommodating under the leadership of staunch ally Edmund Alwin.

Although the “revolution” had promised to bring a complete upheaval of the political system, with radicals like Nietzche and Peter Meise promising to abolish feudalism and make everyone equal, in practice this was not the case. Feudalism was very much intact in a roundabout way, as the nobility assumed the role of the Apostolic class almost entirely, meaning the nobility retained its riches, its power, and its authority over their feudal vassals, just like before, and in some cases likely even profited to a greater degree. However, there were some changes, as the universal hold the nobles had over the peasantry was altered. When the nobility attempted a second revolt in 1520, albeit this resembling a political backlash more than a violent uprising, the peasants successfully organized a strike that threatened to topple the nobility, forcing the nobility to accept the previous compromise in which there was basic representation. In practice the cities of Thuringia adopted the structure used by the free imperial cities of the Empire, with these cities then answering to another council, at least nominally. In practice the nobility controlled said council’s authority, before answering to the Supreme Ratia, which acted as a parliamentarian system for Thuringia as a whole.

1520 would also mark the first year that the Old Government sought to erode the use of currency. Monetary taxation was largely done away with, as the nations’ assemblies, or more specifically the nobility, worked together to institute a central plan for the nation and collect taxation through labor. The first taxation began with the levies of the nation being called to work on national projects, chiefly the creation of supply depots and infrastructure needed to institute further development in the future. In each town a commons area was created, with a fortification being selected to act as the chief center for collection. Henceforth each year the peasantry were to pay a tax to these centers in the form of labor and goods produced. Elsewhile, there was no conventional taxation, and the fruits of the peasantry’s labor was enjoyed by them. The White Knights, founded a decade earlier as a Jungist military order, became enforcers of the new laws, and also as an intelligence and propagation network. Their printing press department became an important part of the historical record of the time, with pamphlets and books on Thinwhitedukism and other topics being readily distributed.

As the situation settled there remained critics of the government who thought due to the compromises made by Nietzche the revolution had not gone far enough. In one controversial act, President Nietzche was forced to send an army to put down a rogue arm of the Great Peasant Revolt, meaning that as the revolt was ending it was its own members who had to help end it, putting a nail in the coffin toward complete upheaval of society. With radical revolt quelled, a sizable percentage of the nation’s assembly would nonetheless come to support radical legislation.

Elsewhere, the Old Government supported Martin Breur and his attempted protestantization of the Primacy of Germany. He became instrumental in spreading Jungism and undermining Catholicism from the inside, but he also eroded the central organization of the church, as most Catholics simply refused to listen to his council, which would later contribute to the creation of the Northern Catholic Church a generation later. Furthermore Breuer became the target of other Jungist reformers around the Empire, as his masquerading as a “Great Synod” was deemed contrary to Jungist teachings.

Bayreuth and Henry-Hugh Feud

In 1521 Thuringia was invaded by Robert of Bayreuth, at the head of an army of mercenaries and deposed or disenfranchised nobles. They argued that the Great Peasant Army, which the Thuringians harbored, had unlawfully deposed many of them or damaged their holdings; numerous escaped Thuringian rebel leaders also were among their ranks. The Emperor supported this invasion and sent Bohemian soldiers to aid them. Bayreuth was initially in a highly disadvantageous position, as it found itself surrounded by Jungist states organized by Hugh the Heir, one of the heroes of the Thuringian-era Peasant Army. Bohemian forces first clashed with the Jungists at the Battle of Plauen, which saw Vogtland switch sides in favor of the Catholic side, despite Hugh’s intimidation. Elsewhere, Bamberg found itself quickly under siege by the Jungists, after Truhendingen suffered an embarrassing defeat attempting to attack Hugh’s army from Nuremberg. For a year Hugh and Robert, two men renowned for their cunning, battled on and off the battlefield. All this continued until the death of Emperor Ottokar, which caused a delay in the war.

Perhaps the last important legacy the Thin White Duke had on the nation was his crucial negotiation with Ottokar I, which led to recognition for the nation and an end to its formative war. In 1522 Ottokar died and was succeeded by his son Jaromir, and according to legend the Thin White Duke either died or disappeared on the same day. According to legend, it is said that the Duke to this day walks among the tallest peaks of Germany, waiting on that mountain for a day when Thuringia needs him most, and then he will return. Under his unifying guidance, peace had been possible in the House of Jenagotha, as although he had a cruel exterior, he had always valued his family and welcomed all within his home, called The Twins. In his later years, the various branches of the family, all with differing loyalties and motivations, had begun to conspire against each other, waiting for the day that the Thin White Duke finally died. Many of his sons had predeceased him, to the point that his eldest son was actually his 17th child, Conrad. However, Conrad had agreed to forfeit his position in the line of succession in exchange for the Duchy of Württemberg, a promise not certain he would keep. Therefore if succession passed strictly to the eldest son, that left his 20th child Hugh “the Heir”. As his moniker implied, Hugh thought of himself as the Thin White Duke’s preferred heir even before his passing.

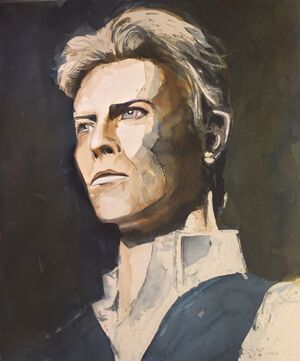

Henry I, who became Apostolic President

Hugh the Heir who became Duke of Thuringia and President of the Magi

The second most likely candidate was the Thin White Duke’s grandson via his eldest son William of Talstein, the former Holy Roman Emperor Henry IX. The rivalry between the two men would lead to a brief civil war in the country, and their feud would dominate Thuringian politics afterward. Although enemies of Hugh attempted to stop him from claiming his succession by trapping him in a siege, Hugh reportedly escaped the city by jumping off the castle walls with a glider device, crashing 200 meters away in preparation for the election. Hugh argued that he was the strong leader needed to protect Jungism and prevent the election of Ottokar’s son Jaromir as Emperor, but his chances were greatly hurt by the ongoing conflict.

Due in part to his position at the head of the army and his large personal domain, which stretched from Nuremberg to Coburg, Hugh had himself crowned Duke of Thuringia. Henry IX meanwhile ruled over Weimar and most of eastern Thuringia along the Saxon border, and was all around just as popular as the self-proclaimed Duke. His clan also included Talstein and Rutha, and Wenceslaus IV de la Marck (his half brother-in-law), who he granted lands to or helped to acquire numerous lands within Thuringia for. There were dozens of minor branches of little note as well, who were all courted or swayed to various factions. Although a “civil war” developed, it was largely not a war fought on the battlefield, but a familial rivalry of who would outlive their siblings and kinsmen, with various plots to outmaneuver each other. Although Hugh initially claimed the ducal title, Henry IX was proclaimed the Apostolic President with the backing of Nietzche and other allies, such as Gustav Jung.

In addition to the Nuremberger and Württemberger branches, there was also Count Louis of Nordhausen, the Saxons under Roger von Jenagotha and the other half Marcks, the Brandenburgers led by matriarch Maria, who were notable for their alliance with the Sommers of New World exploration fame, and he “Elisabethian Fourteen” led by Isidore von Jenagotha. There were numerous children of Elisabeth of Nuremberg who despised the “usurper” Hugh, while others in that branch supported him. There were notable legitimized bastards like the powerful Conrad von Lautertal and Xaver von Coburg, the former a supporter against Robert of Bayreuth, and the latter more independent and distasteful of Hugh.

Additionally in the spring of 1523 the peace with Bohemia and Bayreuth deteriorated. War continued against Robert of Bayreuth until the untimely death from disease, at which point John Hawkwood’s brother Lionel declared himself Count of Bayreuth for several months. Hugh supported George of Ansbach as a rival claimant, who had married the widowed wife of Robert, and whose daughter Margaret had been married to Hugh. Despite Bohemia becoming strained due to Jaromir’s marriage to Joan of France, which necessitated he send support for ongoing French wars, the 1523 Battle of Kulmbach saw Bayreuth pacified under Bohemia and Hugh defeated. The splintering of the Wolfenbund due to the familial conflict in Thuriniga proved advantageous for Bohemia, and the Emperor proposed an alliance with Saxony against Hugh. To this end an invasion of Meissen began, and Hugh’s allies were decisively defeated at the Battle of Freiberg that autumn.

Accepting defeat, Hugh signed a treaty ceding all of Bayreuth aside from the city of Hof and elected to switch sides. He fought alongside the Catholics and attacked his former ally Bamberg, which now supported Henry’s claim. This development forced Hugh and Henry to negotiate, and they agreed to a peace which saw Hugh renounce the Catholic alliance in exchange for the transfer of the electoral dignity to Hugh. George I of Bayreuth was expelled from the country and replaced by a Bohemian ally as Duke. Discontent by his kinsman’s negotiation with the Catholic Emperor, Henry IX distanced himself from Hugh. On the other hand, Hugh the Heir had turned his attention southward from Thuringia. His careful intrigue and manipulation led him to dominate the politics of the city of Nuremberg, and he would serve as Alderman for the remainder of his life. Despite losing territory to Bayreuth under the machinations of the Bohemians, he managed to secure Bamberg in a partially advantageous peace.

He later used his connections in the south to instigate a fairly bloodless coup in Bayreuth against the Bohemian puppet duke, which saw Lionel I restored, in the hopes that he would be still under Hugh’s control but more palatable than a strong Jungist, or Hugh himself. Despite being Catholic and a vassal state of the Bohemians, a secret alliance was formed between the two men, and according to rumors, Hugh seduced Catherine of Palatine to further gain information and influence over the court. George I, deposed ruler and Hugh’s ally, would be slighted by the state of affairs. Hugh had luckily appointed a bishop of the region from among his confidants, Roger Gagern, who blackmailed George into staying in-line after discovering evidence of him breaking religious customs.

End of the Old Government

After the death of the Thin White Duke and the beginning of the Henry IX-Hugh the Heir Feud, several of the nation’s Founding Fathers would exit politics as well. This would begin the decline of the Old Government as the chaotic age of the Founding Fathers stabilized. Sebastian Gauck died in 1523, while Benedikt Nietzche voluntarily stepped down from the presidency, noting that a career in the representative assembly was more fitting. With the foundation of the nation laid by the Founding Fathers, the subsequent generation expanded on Thinwhitedukism and experimented with its implementation, eventually culminating in the creation of the Rätian Union.

Nietzche’s vacancy was filled by Walter Steinmeier, an influential writer, thinker, and representative from Jena. His 1520 treatise Societas Cooperativa elaborated on Thinwhitedukist theory and attempted to propose solutions for numerous practicalities. He stated that in a primitive society, all able bodied persons would have engaged in obtaining food, and everyone would share in what was produced by hunting and gathering. There would be no private property, which is distinguished from personal property such as articles of clothing and similar personal items, because primitive society produced no surplus; what was produced was quickly consumed and this was because there existed no division of labour, hence people were forced to work together. The few things that existed for any length of time (tools, housing) were held communally. According to Steinmeier, the domestication of animals and plants following the Neolithic Revolution through herding and agriculture was seen as the turning point from this society to class society as it was followed by private ownership and slavery, with the inequality that they entailed. In addition, parts of the population specialized in different activities, such as manufacturing, culture, philosophy, and science which is said to lead to the development of social classes.

Steinmeier would note that the this was effectively the state of the first humans as created by God, and the state described by Jesus and the Apostles in the New Testament, but noting the benefits of modernization toward the construction of Christ’s vision, he proposed the cooperative as the ideal government and hierarchical structure. Likewise, he noted that humans have often organized for mutual benefit, through the organization of cooperative structures, allocating jobs and resources among each other, and believed that to this day they could undertake similar organization, citing the Viamala in Switzerland as an important organization of labor toward the completion of a mutual goal. Effectively, all enterprises would be governed either by the community that constitutes the enterprise, or through a mutual social contract between the governed and the owner, for the purpose of adequately sharing the fruits of labor.

These ideas came as a direct result of the circumstances of the time, as Thuringia was well acquainted with the government system of both the Swiss Confederacy and the Hanseatic League, with many early politicians citing either example; it had been a natural consequence to develop from the system of guilds, focused on a particular industry, to band together with their own internal workings, for the purpose of forming a political league, into a similar guild system applied to all facets of society. On the most local level, varying pieces of society, from the workplace, the living quarters, or the field, would organize into a rätia, and elect delegates to represent them in a local assembly for a town or city or region as a whole, often exercising complete legislative and executive power in their respective, small spheres.

Each town’s representatives formed a rätia for an administrative district, and each district likewise elected officials to the Supreme Rätia. The presidency was effectively the head of an executive committee elected by the Supreme Rätia, and was subservient to its legislation and votes. The system was likewise born of the feudal structure that it coexisted with; the highest elected officials were members of a committee that included the former nobility, who together executed the day-to-day running of the districts or nation. As the Thin White Duke said, the government of God "is a government of union," with this theodemocratic polity being the literal fulfillment of Christ's prayer in the Gospel of Matthew: "Thy kingdom come, Thy will be done in earth, as it is in heaven." As he stated in his 1519 Address to the Union, "I calculate to be one of the instruments of setting up the kingdom of Daniel by the word of the Lord, and I intend to lay a foundation that will revolutionize the world...It will not be by sword or gun that this kingdom will roll on: the power of truth is such that all nations will be under the necessity of obeying the Gospel." Thus the governing synod operated under the authority of God and in his servitude toward the building of the kingdom’s foundation.

The Election of 1525 would prove a crucial affair for the young nation in determining its workings, and serves as a microcosm for understanding the Räterepublic. By that time various factions had begun to emerge who differed in opinion over the future course of the republic. Notably the most radical among the assemblies, who called for more persistent action against Catholics, monarchists, and reactionary thought, were the Tauferands, and were generally opposed by the far more moderate Vendemiairians. Likewise the election would be dominated by the issue of the Henry-Hugh rivalry. Ultimately Eduard von Metilstein, a grandson of the Thin White Duke and a conservative representative, would secure the position of president, calling for recovery and non-intervention. The Henry-Hugh Feud was exacerbated by Hugh’s selection by random chance as President of the Magi to replace Sebastian Gauck, furthering his influence.

One of the final issues decided by the Founding Fathers was the codification of the nation’s religious policies.During this time there were numerous interactions between the Starkists and the “Orthodox” Anabaptists; this term was largely an oxymoron and purported by the most popular Anabaptist movement of Thuringia, but there existed no uniform or orthodox Anabaptist doctrine in actuality. In practice there were several movements across Germany, with Thuringia having perhaps the largest concentration of groups and the largest number of adherents, that were only loosely united in their belief regarding baptism. In truth, the Anabaptist movement in Thuringia chiefly had no unifying name, although it was commonly, and perhaps erroneously, referred to as Thinwhitedukism due to its association with that political ideology, of which there was a large degree of religious overlap.

To rectify this problem, Nietzche would work with reformers such as Karl Schopenhauer, Peter Meise II, and various others in the hopes of establishing on paper the Anabaptist doctrine, and unite the various radical fringes centered in the region. Overall not all the theologians could agree; there was a major division between the “Inspirationalists”, who believed they had received direct revelation from the Spirit, and the “Rationalists”, who more plainly rejected traditional Christian doctrine, in some cases even trinitarianism. Around the same time the debate had begun of what doctrine Thuringia technically adhered to. On paper it was a “Jungist Räterepublic”, but as the Jungist movement split into various categories, both Anabaptist and not, it was unclear what this referred to specifically.

The result was the Synod of Jena in 1530, in which many of the greatest theologians of the day were called to form their arguments. This included the Anabaptist writers, mainstream Jungists like Freud and Michael Kierkegaard, Martin Breuer of the “Grand Synod”, and even Starkists from the Hansa. Ultimately all could readily agree that Catholicism ought to be banned. The Anabaptist movement, although distinct and quite contradictory to Jungism, recognized Jungism as “the branch in its family tree”, and the synod recognized Jungism as the state religion, when it was made clear that Jungism the movement could refer to any of the Protestant sects born out of it, not just mainstream Jungism. Effectively this recommended to the Supreme Rätia, with theologian backing, that partial religious toleration be enacted for all those who were at least a form of Protestant.

Oldenburg Crisis and Marx Era

In 1533 in the city of Münster a group of radical Starkists led by layman Gideon Matthias managed to seize control of the city, with Matthias being elected mayor. Partially inspired by extremist factions in Thuringia, he called for redistribution of resources and power within the Holy Roman Empire, the creation of a theocracy, the implementation of strict Anabaptist practices, and preparation for the impending end of the world, effectively making himself dictator. His rule terrorized the Catholic population of the region, sparking surrounding cities to prepare an army to oust him, and polarized the leaders of Thuringia, who inadvertently inspired such fervor.

The happenings in Münster would attract attention from numerous nobles and scholars across Thuringia. While some volunteered to join the mission in Münster and fight alongside the Starkists, many within the Thuringian government would actually condemn the violent uprising, believing it would paint the entire movement and those movements tangentially related in a bad light. Overall the less fringe among the Anabaptists who were firmly established in Thuringia tried to distance themselves from the violent uprising. Among the most radical was Peter Meise II, claimed “reincarnation” of the late spiritualist, and the “Bishop of Finland”, who had ventured back to Germany and organized an army primarily of Thuringians toward an invasion of the Hansa. Meise believed that it was necessary to spread the revolution that Jung had began by force if necessary, and hoped to incite the uprising of the peasantry in overthrowing the Hanseatic League. This was of course contrary to what Jung personally preached, but nonetheless was born out of the same fervor as the Great Peasant Revolt years prior.

Meise would assemble the so-called “Second Blue Army” – referring to the Jungist army that had been assembled to fight the Wolfen War – and marched north to aid the Münster Revolt. Instead of traveling to Münster directly, he instead marched on the unsuspecting city of Oldenburg, after it appeared the city was aiding the coalition against Münster. The city would be captured, leading to Oldenburg withdrawing from the Münster war, with Meise establishing personal rule over the city, in what is known as the Oldenburg Commune. He would be nicknamed the “Flibuster”, as his actions were compared to that of a pirate. Nonetheless, he set about carving a nation for himself, despite his position as a noble being tenuous.

After Meise captured the city of Oldenburg, he set about establishing a number of new policies. He imposed strict Anabaptist doctrine, ordering all faithful adults to be baptised or face ostracization or death. Heavy iconoclasm was ordered, with all the churches and monasteries of the region being looted. Compulsory polygamy was also instituted, and a minor population exchange took place, as settlers from central Germany entered the region. Unlike the Anabaptists who rejected the feudal nobility and royalty in favor of equality for all, Meise adopted royal regalia and an intricate aristocracy. He would create an intricate system of lesser titles, with titles of nobility being given to all his most loyal followers. Famous statesman Benedikt Nietzche would be offered a highly prestigious title, but as Thuringia was not in support of the Oldenburg government, he could not accept, nor did he want to; he would reply that he could not accept a title unless it was truly the will of the people to elect him as such. Nonetheless numerous other reformers were granted some kind of claimed title by the upstart kingly figure. Meise would personally leave the city by the end of the year before he could witness what would happen to Oldenburg. Him and various other nobles would later form the complicated government-in-exile that maintained a claim to the government of Oldenburg long after the destruction of his short-lived regime.

It was in this era that the political theorist Ingo Marx rose to prominence, serving as president from 1529 to 1533. As the centerpiece of the Tauferands, Marx called for greater action against Catholics, and in many ways was the primordial thought that helped birth the Second Blue Army toward the end of his tenure. Prior to his election, Marx had written an expansive treatise in Natural Law, which was inspired by the plight of the faithful oppressed in Catholic countries. He argued for the theory of natural law, in opposition to the divine right of absolute monarchy; the purported contract inherent between a monarch and the governed, he argued, was unethical. It was theorized that in the power vacuum that accompanied the fall of the Roman Empire and other powerful institutions, society had fearfully been coerced or accepted the rule of protectors to fill that void, a role that had been enlarged into the modern feudal structure, that would ultimately be progressively removed in order to return society to the autonomy God afforded people.

He would argue many of these points through religious examples that ironically were similar to Catholic views in some cases, noting that, "For when the Gentiles, which have not the law, do by nature the things contained in the law, these, having not the law, are a law unto themselves: Which shew the work of the law written in their hearts, their conscience also bearing witness, and their thoughts, meanwhile, accusing or else excusing one another." Marx would be followed by Roger von Lautertal, a prominent noble and son of one of the original Conspirators, and the Supreme Rätia became dominated by radicals, many of which calling for expansion of the state through union with their neighbors.

This was aided by the schemes of Hugh the Heir, who had turned his ambitions southward following his expulsion from Thuringia. He managed to dominate Nuremberg and Bamberg, and essentially crafted his own duchy that rivaled that of his kinsman in Thuringia. Henry, meanwhile, had secured numerous alliances across the region, working closely with leaders from Halle and Jüterbog, two cities within the Archbishopric of Magdeburg, in an effort to undermine the Catholic presence. Specifically he formed a close alliance with a minor noble named Peter Hals, who he aided in securing the position of mayor in Jüterbog. Their visions clashed in Vogtland, over conflicting claims of who would serve as administrator. However, war was averted when news arrived of the passing of Edmund Alwin of Saxony, as both men paid their respects to him.

Hugh’s schemes were reignited with his usurpation of Bayreuth. He managed to seduce Catherine of the Palatinate and convince her that the Duke of Bayreuth was conspiring against her son, a potential pretender. Catherine would be manipulated into poisoning her husband Lionel and then writing a secret letter to the steward of the Gerards that he had been poisoned by the Courtenays. The result would be a civil war orchestrated by Hugh between the Courtenays and the Gerards, that would eventually cost the lives of much of Bayreuth’s nobility. Ultimately Hugh would marry Catherine himself, giving himself rule over her lands, and then having her killed in a fake suicide plot. As regent for Elizabeth he emerged as a prominent negotiator in Bayreuth, albeit an untrusted one. By 1533 he had eliminated the Duke, allowing him to become regent, with ambitions to unite Bayreuth with his lands. This would not come to pass, as in late 1534 one of Hugh’s own sons shot him with a crossbow in his bedroom, his true motives never entirely known.

Establishment (1534–1595)

Declaration of the Union

Henry IX had outlived his great rival, and set about undertaking a vision his grandfather had once dreamed of. Henry would dispatch soldiers to Saxony to help oust the Catholic claimant Edmund of Jessen in favor of Wolfgang I. Having united the various Jungist allies of the region in a common war, the leaders of the Wolfenbund on 2 February 1534 would declare the creation of the Union of Rätian Jungist Republics, as a loose confederacy of already allied, like minded nations, with Henry as its Apostolic President. Roger von Lautertal would step down in order to allow for immediate elections for the union, and was succeeded by Theoderic Rood, while Martin Breuer succeeded Hugh prior to his death.

Rood had been a reformer and deputy bishop from Saxony who had worked closely with Gustav Jung. His government ushered in the so-called “Theologian’s Government”, as politics became headed by famous reformers, notably Rood and Martin Breuer. The first issue the new government tackled was the sudden death of Hugh the Heir, which caused chaos in his little empire. His eldest son Gedeon was secure in his position as Duke of Thuringia, while his brothers debated the remaining territories that Hugh had loosely united. However, Henry IX would oversee all these territories being loosely united into a Räterepublic, known as Franconia.

The second issue came after the fall of Münster and Oldenburg, as many of the radicals of that region fled back to Thuringia, although most of the leaders appeared to go into hiding in Finland or elsewhere. The call from the Hanseatic League to capture and execute those responsible for the attack sparked serious debate. The more conservative within the nation argued that it was the state’s duty to execute the Emperor’s justice in prosecuting those who broke the peace. However, others within government argued that it would be a slippery slope to try to prosecute people for the act, an act not committed in or against Thuringia, an act that could not readily be proven and prevented into turning into a witch hunt, and an act demanded by the notably Catholic Hansa. The most radical among the government even argued that the attackers were in fact heroes, not criminals; they were independent people who rose up against tyranny in fulfillment of Jung’s vision, they reckoned. Ultimately it was Benedikt Nietzche, the famed statesman of the Supreme Ratia, who gave an impassioned speech saying that Thuringia would not hunt down the Hansa’s alleged criminals.

Nonetheless, multiple cases were brought before court in Thuringia, in which known wrongdoers during the affair, especially those who profited off the endeavor or had malicious intentions that both sides would find detestable, or those whose fanaticism against Oldenburg was spilling over into a threat against the Thuringian government, were tried and punished. Beyond that, the government did not actively seek out all those involved. Among those adamant about bringing as many people to justice as possible, and for expanding the government’s reach to persecute those responsible, was Representative Oskar Bothmer of Molsdorf. He traveled to the Hansa in person at the head of a party of envoys, bringing the head of one famed leader of the revolt personally to Lubeck, in the hopes that his genuine display of zeal toward the Hansa’s goals would endear them away from souring relations with his home country.

Gunpowder Plot

In 1535 the Gunpowder Plot occurred, which was an attempt to blow up the College of Cardinals by an organization calling themselves the Black Hand Society under a Hessian leader, Hans Gruber. This escalated into a major crisis that polarized the Jungist-Catholic world. According to Catholics, the plot was ordered by famous Jungist Agnes, Duchess of Hesse in a direct attack against the Catholic world. Agnes had previously been excommunicated prior to her conversion, was an enemy of the Papacy, and had previously been implicated in attempts to assassinate members of the House of Lenzburg via her association with Dolphus Thurn. However, Hesse argued that the attack was actually a false flag attack meant to paint Jungists in a negative light and spark outrage against them.

Both the government of Hesse and the Thuringian government by and large condemned the plot, srtressing that Jung had been against violence, and that wanton murder against the pope instead of a fair trial was at best vigiliantism and was misguided. As such Rood’s government urged Hesse to aid in hunting the Black Hand organization, as such a thing threatened the stability and safety of Hesse as much as it threatened the Pope. On the other hand, many were also quick to point out that Jung was in fact murdered as well, with one of the leading theories at the time being he had been murdered by the Pope. As such, there are some in government who believed the death of the Pope was merely retribution for violence that they started. Additionally, the propaganda issued by the Papacy regarding calling Jungists in league with Satan certainly hardens people’s resolve and only turned them more furious at the other tribe.

Investigations of both Catholic and Jungist origin were begun regarding the attack, with the narrative that it was a Catholic plot gaining popularity in Thuringia. The most outspoken of this opinion was Martin Breuer, noted Primate of Germany and head of the Catholic Church in Germany—at least in theory. When he published his findings, which included numerous interviews and confessions, he ruled that the attack was orchestrated by a radical Catholic group, or a group claiming to be Catholic. As such, this became the official opinion of the Thuringian government by late 1535, and what was published nationwide and beyond, and was also what Breuer prescribed to the Catholic and Jungist churches under his authority. However, it became obvious that this outcome would not satisfy all. The mainstream Catholic opinion remained that the attack was planned by radical Jungists as that would make for the most simple explanation, and was one that would fit the agenda of the Catholics regardless. Nonetheless, mainstream Jungists distanced themselves from acts of terrorism and that event, and even showed solidarity toward the Catholics and those effected.

Controversially Rood ordered a diplomatic mission be sent to Italy to apologize on behalf of the church as a whole, and to demonstrate and make plans toward Thuringia’s ongoing response in hunting down and persecuting the Black Hand. This was because Rood believed that such radicalism could harm Catholics and Jungists alike, and would only further the divide between them. Benedikt Nietzche would remark:

- “The terrorist order has remarked that they are Catholic and that they find their actions justified to catalyze violence against their Jungist enemies, and the Catholics deem they are no Catholic order. And I agree. Others claim the terrorist order has remarked they are Jungist and that they find theory actions justified to catalyze violence against their Catholic enemies, and the Jungists deem they are no Jungist order. And I agree. It is antithetical to Christianity, to the point of breaking any scripture you attempt to bend, to claim that they are Catholic, Jungist, or Christian at all. As such there is no dichotomy to be falsely applied, in which we must side with that of violence, in opposition to our true values, to antagonize the other tribe. Neither tribe welcomes such barbaracy. And both tribes are united in a common goal today.”

Equally as controversial was the implementation of an “inquisition” in Thuringia for the first time in forty years, to hunt down those responsible for the attack. However, it was crucial to the government that no Catholic of Papal agents set foot in Thuringia – such an act would be an infringement of Thuringia’s sovereignty and complete rejection of any Papal authority, and would likewise be very unpopular in the wake of the Pope’s actions decades prior in Thuringia – but nonetheless the Thuringian government still persecuted such radicals to the best of their ability independently. Thuringia also issued a declaration that any attack against Hesse would be viewed as an opportunistic and illegal powergrab, and a wrongful attack against those not responsible for the attack, and the army was raised in case of conflict.

Elsewhere, there was a small minority of people who supported such an attack, but they were few and far between. Among the peasantry, misinformation had notably charged many to have a zealous opinion against Catholics. When news reached Thuringia from Rome of the Pope’s speeches calling for violence against Jungists and the destruction of lands in Germany, this further outraged the people of the nation, and was viewed as a slap in the face to the moderates in the government that had promoted peace. Nietzche would remark that he had done what he could to keep the floodgates closed, but if another insult arrived from the Pope it might be the final chip in the wall. Noted extremist and exile Peter Meise would remark that blowing up the College of Cardinals was actually extraordinarily good and the right thing to do. He would publish a book on the subject at some point after the event, writing numerous defenses of the action, chief among them that a rationale for why the attack was a reciprocal and justified counterattack against an invasion the Pope started, and that the Pope as Antichrist should be stomped out at every available avenue by righteous Christians. Granted Meise’s works would not reach Thuringia for a decade after, his book becoming an extremist holy grail hard to come by unless within a select number of secret circles.

Perhaps the most potent and scathing opinion of the affair written to the Papacy by a major figure was the rebuttal given by representative Ingo Marx, who wrote the following dissenting opinion:

- “The legacy of the Pope is violence. When their authority is challenged, the proven, favorite instrument of the deceiver is the act of violence in the form of crusades, inquisitions, and killings, to silence those who wish to rebuild Christianity against his graven image. It was indisputable that Konrad Jung was a peaceful thinker who condemned violence of any kind: that is the foundation of Jungism. Jesus Christ once said, ‘But I say to you, Do not resist the one who is evil. But if anyone slaps you on the right cheek, turn to him the other also. And if anyone would sue you and take your tunic, let him have your cloak as well. And if anyone forces you to go one mile, go with him two miles. Give to the one who begs from you, and do not refuse the one who would borrow from you.’ (Matthew 5:39–42) It is this doctrine that Jung followed, and that all the Apostles and early church fathers followed, but somewhere along the way this was lost by the Pope; he founded his modern church on a different foundation, not the one that Peter founded his upon. To claim that the Pope is related to Peter would be a great travesty, as it has become clear that the modern Pope is a different institution than what Jesus would recognize, and thus it became in the hands of the reformers to right this egregious masquerade.

- Likewise, just as the Pope or his adherents murdered the innocent man Jung, they have a continual history of foreign intervention to the detriment of the world and to the complete embarrassment of Christ. The Papacy has supported countless crusades called erroneously in his name; wars of political and sacreligious aggression, contrary to what can be gleaned from the Word of God. In a long train of abuses, comes their most recent act of barbaric pillage: the so-called Thuringian Crusade. In 1492 an army of zealots came to Germany, not to spread the message of the Lord, but to rape and pillage the innocense of the community. It was to the detriment of all that this occurred, from their great killing of innocence, to their destruction of Germany, to their humiliating portrayal of Christianity, which ironically inspired the faithful Jung to begin his journey in the first place.

- It is your continual embarrassing of the church, Pope Francis, that compelled the people of the world to seek reformation or outright schism. I pray there comes a day when you practice what you preach, and you are informed of the teachings of Christ. When that day comes you will end your disastrous wars of conquest and rule as a non-secular ruler. You will end your centuries long inquisition that has murdered millions of Christians to meet your agenda. You will cease harboring fanatic warriors who seek to spill the blood of your fellow man. Until that day, you cannot expect there to be no resistance to your tyranny, and for groups from all across the religious spectrum to speak out, and should they not be heard, then violence becomes in their mind necessary. Let the alleged plot be a wake up call, that if the Church does not reform, it will be the death of both Jungist and Catholic faiths, and the utter destruction of Europe as a whole, and the diminishing of all of us for the sake of achieving your egotistical reign. Thus, we Jungists continue to condemn all acts of violence from either side, but we cannot act surprised that when the Pope throws the first stone 1,000 times, that one might bounce back in return and graze them.”

Ultimately, with all these various opinions floating around, the government would issue a statement that the Pope’s decree that, “Jungism must be declared as dangerous to the peace and all Jungists in their lands must be destroyed” must be repealed, if to remain in good conscience. The Holy Roman Emperor, Jaromir I, would issue a decree that no foreign intervention against German states would be tolerated. He noted the earlier “crusade” against Thuringia around the election of Henry IX, and how it had been detrimental to the Empire and Christianity as a whole, and ironically a major catalyst in creating Jungism in the first place. Therefore the Emperor responded that he would not allow the Pope’s inquisitors, soldiers, etc., to invade any part of the Empire, as he personally would be enforcing religious standards, and that any sudden crusader army invading would be met as an attack on the Empire. Nonetheless the Emperor demanded many concessions from the Hessians in the form of cooperation, expecting that radicals of any denomination would be persecuted.

Second Party Era

Although the early presidents of the Rätian Union were often independent of any political party, this began to rapidly change, especially in the later years of Henry I. One of the most prominent parties of the early union, the Tauferands, would begin to splinter in the mid 1540s; one of the party’s outspoken leaders, former president Ingo Marx, died in 1548, leaving unofficial leadership to Marcus Cranach. The “Cranachites” differed from Tauferands in their more moderate approach to Reformation, as personified by Cranach’s characteristic indecisiveness. Under his leadership the country’s stance toward the ongoing Amiens War often flip-flopped.

Cranach’s successor in 1549, Kurt Eisner, came into office through compromise between the various Tauferand factions, although he became more involved in foreign affairs. The Eisner government would take a moderate stance in the War of the Three Henrys in favor of Henry the Protector, although after his death Eisner helped negotiate the rise of Henry X, Holy Roman Emperor to the throne of Bohemia once more. Eisner would later be replaced by Xaverius Kreittmayr, whose popularity came from his wartime heroism during the Kerpen War.

During this time the Supreme Rätia began to organize itself into a “right and left” division, as more conservative representatives, especially nobility, sought to separate themselves from lower class members by sitting in the more prestigious position to the right of the Apostolic President. Despite later controversies changing the exact positioning of the assembly, the terms would become commonplace in political discourse. This event would also highlight a major problem developing within the government. Since the beginning of the nation and the Great Peasants’ War, the assemblies had been composed of those elected by more local rätia. In theory this many any person from any walk of life could eventually succeed to the Supreme Rätia, but in practice those of high birth, prestige, or nobility would often find themselves the ones elected at the local level, in addition to many nobles being representatives automatically by virtue of other means to the assembly.

This began a division within the government, as the nobility disliked working with peasant representatives, while the most radical lower class representatives disliked the claimed exceptionality of the nobility. On the far right of the spectrum were monarchists and ultraconservative members who sought to limit participation in government, vest greater power in the landed elite, and disenfranchise voters. Others on the right included the various powerful families of old, the most notable of which being the Jenagothas. Since the Thin White Duke, hundreds of Jenagothas had been part of the nation’s government, and the leaders of the family had a vested interest in ensuring they continued to dominate, although there were notable exceptions within the family. A slightly more radical branch was the Bankerts, nicknamed the “Great Bastards”. These were the hundreds of illegitimate descendants of the Thin White Duke that existed across the nation. Bankerts tended to often still be well landed and wealthy, as they were often trusted by various rulers of Thuringia as allies, but conversely many other Bankerts were the opposite, especially as the time since the Thin White Duke increased, and these descendants spread in many directions.

On the left were those who opposed the nobility and sought to make the government more inclusive and representative of the common people. Left-leaning politicians generally were against feudalism and disenfranchisement, with some more radical members even opposing the Jenagothas and other prestigious dynasties. The far left, most radical elements of the assembly favored complete abolition of feudal titles, nobility, and aristocracy, and even a complete change to the role of the apostolic president. In addition there was the religion angle; political parties differed on the role religion should play in the government, and to who religious authority should ultimately rest. The Thin White Duke had personally advocated for the “Vanguard”, a system in which power had to be temporarily vested in the nobility and other officials to ensure the nation’s immediate survival. This was taken literally by the newly formed Vorhut, or Vanguard Party, comprised of right-center moderates with highly Thinwhitedukist religious beliefs, and was combated by the Millennialists, who sought for the fulfillment of Thinwhitedukism more expeditiously.

One of the most immediate talking points of the Thinwhitedukists was the concept of “communalization”, or the expansion of communal land to the peasantry, whether by means of agricultural, Steinmeierian cooperatives, or by centralization and standardization under a state committee. During the middle ages the manorial system dominated, which saw the vast majority of the peasantry living on and working rented land on behalf of a lord. The three field system was common, which saw fields rotated between growing wheat, barley, or being left fallow for a year, and these fields were divided into disconnected strips managed by different families. Additionally there was common land, which anyone could use freely. Across Europe, especially in England, the practice of enclosure developed which began to threaten this agrarian lifestyle. Land that had previously been held in common began to be enclosed and made the property of wealthy landowners. Peasants were often pushed off their land by these developments.

These practices began to trickle into Thuringia, first by the old aristocracy which sought to rebuild their holdings and increase efficiency for themselves. Additionally there were artisans who saw the ability to increase profits, for example, by enclosing fields to make sheep pastures in order to take advantage of the demand for wool. The consequent eviction of commoners or villagers from their homes and the loss of their livelihoods became an important political issue, as the resulting depopulation was financially disadvantageous to the nation, potentially increasing banditry, depopulating the workforce, and weakening the military strength of the union. The Thinwhitedukists argued these practices had to be reversed, and that land should be unenclosed or communalized further. The most radical among them argued that the very nature of a manor system with an overarching lord was antithetical to Thinwhitedukism; the centuries old practices of the community coming together to manage the farms, make agricultural decisions, and sustain themselves demonstrated that each village could form a rätian and that the lord was not needed.

The Rood government toed the line on these debates and ultimately collapsed in 1537, leading to the election of Marcus Cranach. Cranach formed a coalition government of moderates and left-leaning Thinwhitedukists, which proposed that at every opportunity it was the nation’s duty to free serfs from their indenture to the manors. Without the support of the nobility this could not be carried out nationwide, but nonetheless began in earnest wherever possible. The wool industry and other enclosure-rich enterprises became scrutinized by the government, and during this period farms and minor villages were consolidated into larger towns. Unbeknownst to the Thinwhitedukists, a poor harvest would occur the following year amongst the chaotic reshuffling, causing a famine to break out. The Cranach government would investigate the matter and attempt to placate the famine, before Cranach’s fall from government in 1549.

Although that year’s weather had played a role in the event, it was noted that the nation in particular was affected more so than its neighbors, leading the government to find disease and climate considerations implausible. While Cranach’s policies were derided, he also pointed to several other man-made factors. Firstly, it was notable that parts of the Rätian Union previous to this had experienced a major boom in population, especially as Thuringia recovered from a brief decline in the late 15th century as a consequence of the Catholic crusade, influenced also by the introduction of changes to the family unit brought on by the introduction of Jungism, which saw families grow exponentially and perhaps beyond the manageable level of the government. Secondly, it was noted that several territories had been recently and hastily incorporated into the union after the death of Hugh the Heir, and these territories had experienced several years of devastating conflict. And so it was speculated that the damage done to the Franconia region, paired with the lack of infrastructure built by the Union on account of only recently acquiring the land, is what led to the famine—this was a leading factor considering the famine appeared to be largely in the south of the nation, not in the province of Thuringia, for example.

And lastly there was a highly contentious point made within the government, that the famine had been purposely caused or influenced maliciously by Catholic dissidents. There was a limited amount of evidence pointing to this theory, but it ultimately was the one the population fixated upon in large part, especially in wake of the fact that strangely the famine had specifically, if not strategically, befallen the Union and none of its Catholic neighbors. On the subject of Catholics or Crypto-Catholics, historians believe the population of Catholics, hidden or otherwise, was essentially zero in the core territories of the Union like Thuringia. This is confounded by the fact that in the earlier war with Bohemia, in which the Emperor occupied large portions of the future Union, at a time when it would have made sense for Catholics to aid the Emperor or contact him in some way, there was no record of any such uprising or incident, from either Thuringian or Bohemian sources. Likewise, historians would note that there was no mention of any Catholics in Thuringia until the late 1600s, when Italian merchants settled in the region for the first time, and could not report to find any similar communities.

However, the case was much different in other, newer provinces of the union, such as Franconia. The Duchy of Bayreuth had been officially Catholic until only a few years ago, and as such essentially all of the Catholics present within the Union were present there, aside from a few exceptions: a notable minority in the city of Nuremberg, a large concentration in Bamberg, and a minority in the lands of Edmund of Saxe-Jessen, perhaps one of the only Catholic nobles existent in the Union. As such, notable Jungist-Catholic sectarian violence, and the ensuing famine, was effectively only in Franconia. The outbreak of violence is often looked upon as another phase in the long Bayreuther conflict; the death of Hugh the Heir had left a power vacuum, which had not yet been filled, making conflict inevitable and planned at this time even before the famine. Likewise, Bayreuth had been for most of its history a Bohemian vassal, and a state largely supported by Bohemia through military intervention, leading to their involvement once more not being surprising.

The issue would galvanize the nation, with a radical Marxist statesman named Rudolf Stern being elected. Under his leadership military action would be called to assert the claim of one of Hugh’s heirs to Bayreuth, and put down Catholic uprisings in Franconia as a whole. However numerous political developments would occur as well. As had been prevalent since the 1510s, the provinces had begun a transition away from a pecuniary taxation system, with citizens contributing to the government in the form of regular labor and service, and a portion of produce created. This policy had enabled the building of new infrastructure across Thuringia for the purpose of alleviating famine; supply depots, common areas, and communal stores of resources allowed for increased and more productive allotment of agricultural yield. However, a fault within the system would be exposed during the Franconia Crisis, as it became clear this system was not yet equally implemented outside Thuringia, and with an outbreak of rebellion, workers were instead paying their service in the form of military service, and fighting prevented large-scale construction.

Additionally, the Stern Government attempted to expand the Nahrungsmittelverteilung (“food appropriation”) principle, that allowed the government to collect a certain amount of food annually from the peasantry, to ship relief to the southern provinces. Although this worked to some degree, extended food confiscation became controversial, as Thuringians feared the effects of the famine spreading to them if they continued to prop up downtrodden regions. This would culminate in the Ebern Protest, in which 900 armed peasants refused to comply with appropriation orders. The revolt would be suppressed, but in the wake of such an event the Stern Government decided to suspend the appropriations. In its wake Stern would create a new economic policy, which included a set of guidelines to improve economic conditions in the following years.

The most tangible effect of the policy was the gradual but temporary weakening of mercantile control over trade, the diminishing of tariffs, the legalization of surplus selling on the open market, and the dehalting of enclosure. This measure would be vastly controversial within the leadership of the government, but Stern argued it was a regrettable but necessary measure in order to combat the crisis, which would be repealed once the positive effects of such a thing had been quickly exhausted. Furthermore, increased scrutiny in conversions from Catholicism began, with harsher punishments for illegal Catholicism also considered. Prior to this, and further giving credence to the claim that Crypto-Catholicism was likely non-existent in Thuringia, the primary issue on the minds of theologians and government officials was not Catholicism but rather Crypto-Kafkaism, as it was believed that Reformed tendencies were beginning to seep into the Union.

Internal conflict

The mid 1500s saw the Rätian Union enter into a period of instability, which culminated in the Rätian Civil War. Chief among this conflict was the debate of who held ultimate authority in the Union, sometimes nicknamed the “Optimates and Populares” debate of the Union. Thinwhitedukism had created an atmosphere in which republican, council government dominated the nation, but at the same time an ancient nobility was left intact, who was incentivized to disrupt the power of the commoners and reestablish monarchical control. This debate had broad social and economic consequences, which undermined central authority in the Union, and ultimately gave rise to laws protecting the supremacy of the Rätia in governance. The conflict was made more complicated by a religious debate—orthodox Jungists feared the emergence of Kafkanist and Catholic reemergence in Rätian society, and religious groups formed radical parties that called for the purification of the Rätian church, or its dismantling. These internal conflicts paralized the ability of the Union to respond to foreign crises. Although the future Gedeon II, Duke of Thuringia led forces in support of Jungists in the Trier War, the nation as a whole failed to respond, and the war was ultimately won by the Catholics. This placed the nation in a poor footing in the leadup to the Forty Years' War.

The nobility and wealthy landowners in the country continually pushed for greater means of enclosement in the following century, however, these petitions were often blocked by the assemblies of local villages, or vetoed by the upper echelons of the Rätian government as ideologically infeasible. Laws were passed in 1540s prohibiting the ownership of more than one farm by a single individual, prohibiting the conversion of communal farms to pasture, and ordering compensation for disrupted communities, which was made via the confiscation of half the value of any newly created pasture until compensation had been made. In 1554 a widespread peasants’ revolt broke out in Thuringia, in which farmers pillaged private estates and destroyed fences, protesting what they saw as the confiscation of the lands and the betrayal of the government to safeguard local communities. The rebellion would be suppressed by military force the following year.

The mid 1500s saw the coalescing of various far left and Millenialist elements into a political movement, nicknamed the Runden (“rounds”), as their members often sported a simple, round haircut, in stark contrast to the high fashion of the nobility. This group was largely made up of “first generation” of Rätians, i.e. those born after the establishment of the Union, and those who came from an unprivileged background—peasants, elected assemblymen, and self-made artisans. The Runden were those that had grown up reading and preaching Thinwhitedukist and radical Christian rhetoric; they opposed absolute monarchy, the nobility, serfdom, and the expansion of enclosure. Seen as too radical by the prevailing leadership of the Supreme Rätia, the Runden were repeatedly rebuked from leadership, despite representing a much larger support base. In 1555 a coherent ideology began to spring forth in opposition to the militant crushing of the early peasant rebellion. As articulated by leading Runden member Torsten Koch: “while the special privileges remain, the powerful will use their powers to crush the just, and to undermine the principles of the state for personal gain.”