Music of the United Commonwealth

The music of the United Commonwealth reflects the country's history as a producer and source of musical creation, and its pluri-ethnic population through a diverse array of styles. It is a mixture of genres influenced by the music of the United Kingdom, West Africa, Ireland, Latin America, and mainland Europe, among other places. Although home to numerous state-supported musical institutions, the United Commonwealth has also carried out periodic content censorship; according to Aeneas Warren, "Every artist, everyone who considers himself an artist, has the right to create freely according to his ideal, independently of everything. However, we are Landonists and we must not stand with folded hands and let chaos develop as it pleases. We must systemically guide this process and form its result."

The earliest inhabitants of the land that is today known as the United Commonwealth were the Native Americans in the United States, and they played its first music. Beginning in the 17th century, European immigrants primarily from the United Kingdom, Ireland, France, Germany, and Spain began arriving in large numbers, bringing with them new instruments and styles of music. Additionally, the American slave trade introduced large numbers of people from West Africa, who brought with them their own musical traditions. Subsequent waves of immigrants from around the world have also contributed to the United Commonwealth's musical tradition. Despite censorship laws and regulations, the early 20th century saw the development of a rich avant-garde tradition in the United Commonwealth, as well as the proliferation of popular musical genres such as country, jazz, and rock.

History

Beginnings of Popular Music

During the 18th century the foundations of what would become popular music – as opposed to classical or folk – began in colonial New England, with choirs and traveling singers like William Billings becoming popular. Musical techniques such as the Shape note, Lining out, and the Sacred Harp were first developed in this context, and later spread across the Thirteen Colonies. In the southern colonies, musical accompaniments containing these techniques became an integral part of the First Great Awakening, and spread both among white and black (both slave and freed) populations. "Spirituals" became common in the early United States as popular music based on religious hymns and traditions. By the time of the American Civil War other genres had begun to take shape, including popular comedic songs often performed by minstrels in blackface, as well as ballads, the latter being repurposed by both sides of the war as patriotic songs. Among the African enslaved community a number of traditions emerged out of the spiritual genre, such as the ring shout, an energetic religious ritual in which worshippers shuffled and stomped their feet around a circle. At the back end of the 19th century this evolved into the cakewalk among newly freed Africans, and later catalyzed the ragtime musical style as pioneered by such composers as Scott Joplin (c. 1868 – 1917). Around the same time mainstream America became enthralled by the brass band marches of such composers as John Philips Sousa.

One of the centers of American music was Tin Pan Alley, a collection of music publishers and songwriters located in the Flower District of Manhattan. Songwriters from Tin Pan Alley came to dominate American popular music, providing sheet music for popular dance numbers. Similarly, the Vaudeville tradition also emerged from popular, comic musical theatre. Music halls became the epicenter of music for urban Americans, with theatres performing musical acts beginning to gradually overshadow all other acts of the time. Subsequently, the entertainment industry began to be dominated by a small number of conglomerates that controlled these theatres as well as the sheet music business, where hit songs could often sell over a million copies. With the invention of the phonograph in 1877, the music industry was revolutionized into a market for recorded musical numbers by charismatic performers, rather than sheet music dominated by songwriters. During the formative years of recorded music, numerous musical trends and fads would be attempted to attract listeners, many of which having a lasting effect on the musical landscape. The shift to recorded music would be a slow process, as theatres attracted those who were unable to afford the new technology. In cities such as Memphis, Chicago, and New Orleans early jazz and blues, two distinct but related genres, became to take shape and attract mainstream audiences. Early record companies such as Okeh Records launched the field of "race music", primarily consisting of blues targeted at African American audiences.

Music would play an important role in the country during the Continental Revolutionary War of 1917–1920. At the beginning of the conflict popular music often included patriotic and enthusiastic marches, and popular songs were often composed during the war to raise the morale of soldiers and civilians alike. However, as the war continued popular music tended to incorporate themes of dreaming about the end of the war—"When the Boys Come Home" is a prominent example. Initially many Americans held a romantic view of war due to the relative lack of radio coverage reporting the conditions of the war, however, as the conflict came to encompass the entire country and bring battle to the doorstep of many Americans, this romantic sentiment quickly changed, as reflected in popular music of the late 1910s. Alternatively, the Continentalist Party also saw the merits of music during the war, and produced a number of pro-Landonist records. Landonist leader Zhou Xinyue was perhaps the most enthusiastic about music as a propagandist tool, later inspiring the founding of Associated Broadcasting, a multi-media broadcasting company. Anti-war songs of all kinds also emerged, although these were almost unanimously banned from the music-hall stages for fear of government censorship or punishment. Famous antiwar songs were often tongue-in-cheek, such as the sarcastic "Oh It's a Lovely War", or "The Military Representative", which touched on military tribunals. Antiwar and antiestablishment songs instead grew outside the mainstream eye.

Post-Revolution Period

In the aftermath of the Continental Revolutionary War and the implementation of Landonist governance in the country, the music industry entered into a period of chaos and uncertainty. Prior to the war an exodus had already begun among the entertainment industry; attracted by the prospect of warmer climates, cheap labor, and less government control, production companies migrated in droves primarily to neighboring Sierra. Harsh patent law and monopolistic practices by the conglomerates of the east coast was also a major force in pushing out filmmakers and music producers, who instead chose Porciúncula as it was outside the grasp of these patent holders. Another wave of migration came during the war and immediately after it, as creatives and people of all walks of life fled the destructive conflict or the unstable regime destined to follow. This had an immediate effect of a brain drain in the fledgling United Commonwealth. The remaining entertainment conglomerates that hadn't fled the country suffered bankruptcy during this period – production of music records quickly became unprofitable and later was stifled by the government as nonessential – or were forcefully broken up or restructured by the Landonist government. From 1922 to 1928 the National Board for Industrialization and Cooperation (NBIC) was designated as the sole operator of the economy, which prioritized infrastructural rebuilding of the country often at the expense of luxury goods. In 1923 Seamus Callahan came into power as the country's paramount, and he expanded Kentucky Bend and other re-education camps across the country. Within the next five years the country's entertainment industry had essentially been dismantled, as capitalists, business magnates, and industrialists were arrested, brought to these camps, or killed.

The exorbitant wealth of the industry tycoons that proceeded the war became distained during the economic hardships of the Weeping Twenties, best epitomized during the Continental Book Burnings, where thousands of pre-war recordings were destroyed. On 8 April 1924 the National Committee issued the "Action against the Reactionary Spirit", which called for numerous books, records, and other works of art that portrayed or celebrated capitalism, nationalism, or other reactionary ideals to be destroyed. Although not all music recordings were labeled as such, the recording industry as a whole was looked upon by many as a purely capitalistic and exploitative industry, in stark contrast to the less financially prohibitive theatre which catered to the pre-war proletariat, and as such many carried out the willful destruction of music records and other symbols of the industry with zeal. On 20 August 1924 one of the largest such events would be carried out in Crosley Field, one of the spiritual epicenters of the Landonist revolution, as 25,000 musical records were burned primarily by members of Callahan's Kontimacht paramilitary group, students, and youth organizations.

During this period the void left by the collapse of the old music industry was eventually filled. A resurgence of the theatre began in the middle of the decade, spearheaded by Broadway in New York City. The dismantling of music copyright brought numerous songs and compositions into the mainstream, where they were remade or repurposed freely, much to the dismay of the former copyright holders. In Chicago the city's first Landonist council ordered free admission to such shows and helped to repair entertainment to aid the beleaguered population. The Little Theatre Movement eventually developed out of Chicago and spread nationwide, promoting cheap or free entertainment to replace closed down cinemas and older venues. The more populist, cabaret-like socialist operas from cities such as Philadelphia also grew in popularity. In 1927 this wild era began to come to a close, as organizations such as Manhattan's Songwriters Council emerged as the city's paramount guild for music producers and songwriters. New York would become the first city in the United Commonwealth to have a guild police copyright and theatre productions in the absence of a government apparatus to do so. In 1928 the laxing of government command over the economy lead to the creation of several music enterprises, which were allowed to produce, manufacture, and distribute consumer goods, although they could not engage in other business-related activities such as marketing or financial decisions.

Music itself during this period underwent a massive transformation. American nationalist music, marches, and other pre-war popular genres had come out of vogue by the horrors of the conflict, and across the board art began to reflect society's doubt toward the beliefs and institutions of the past. The traumatic events of recent times altered basic assumptions, and America's perceived ascendancy as a nation exceptional from the rest was shattered; the advancements of the 19th century had not made war unviable as previously hoped, nor did America's institutions safeguard its people from corruption, wealth inequality, or squalor. Realistic depicts of the world seemed inadequate to describe this sense of trauma or the horrors of the war felt directly by the nation, and popular art of the early 20th century diverged toward that of the surreal, morally ambiguous, or nihilistic. Works such as All Quest on the Appalachian Front (1930) rejected moral progress in the face of senseless slaughter. Others sought to question America's previous fascination with consumer culture—including popular music, Hollywood, and advertising. The 1920s saw a creative explosion among the avant-garde, in what became known as Continental Futurism, which espoused the rejection of the past, academies, and urbanism, and a celebration of modernism, cultural rejuvenation, industry, and youth. Inspired by the "revolutionary spirit" of the era, musical experimentation intensified, leading to the creation of such technologies as graphical sound and the use of early electronic instruments such as the theremin. The rejection of tonality in chromatic post-tonal and twelve-tone works, as well as metrical rhythm became popular among continental performers. On the other side of the spectrum, Englishman T. S. Eliot would reject American culture from a conservative perspective. Popular classical composers during this time included Scott Bradley, whose Schoenberg-inspired atonality was later featured in a series of 1940s propaganda cartoons, and Charles Ives, one of the first composers to engage in systematic use of experimental music and techniques. Less structured pieces involving conductor-less orchestras also became popular.

On the other end of the spectrum, neighboring Sierra emerged as the leader in popular, commercial music and music recording. A market soon emerged for Sierran-pressed records in the United Commonwealth, which catered to the country's elite. However, this was rejected by the Continental Party as Sierran "bourgeois principles", which sought to undermine the fledgling Landonist government. Beginning in 1927 the Central Congress cut off connections to Sierra and the rest of the "reactionary world", and rejected Sierran media as antagonistic to the Landonist values of the nation. More progressive music unions and groups who thrived off Sierran exposure, such as the Association of Contemporary Musicians, floundered under these new policies and were replaced by such groups as the Council of Proletarian Musicians, which rejected all foreign music ideals, seeking instead to encourage "traditional Continental music". Infighting in the group eventually lead to the ascendency of the Continental Musician's Union (CMU), which with the backing of the Department of Culture became the official state guild of musicians and music producers in 1930. By the end of the decade state-sponsored censorship of music and the arts intensified, to dismantle any last vestiges of reactionary, capitalistic, or foreign music in the United Commonwealth. At the onset of the Depression of 1931–1934, musicians who hoped to gain party funding were obligated to submit all works to the Musician's Union before publication, officially to help guide young musicians toward successful careers, but in practice to control the direction of new music nationwide.

Under Seamus Callahan and the Landonist censors, the Department of Culture sought to reel in the experimentation of the modernists through the promotion of "Landonist realism", a style of idealized art that characterized Landonist values, such as the emancipation of the proletariat. In the field of music this meant music infused with a sense of struggle and triumph that uniquely reflected Continental society. Composers were expected to return to traditional techniques that created a through line to America's rustic and populist musical past. Continental music during this period served as an important propaganda tool, glorifying the proletariat and the Landonist regime, as well as Callhan's personal greatness, a trend which he attempted to stop on more than one occasion. Throughout the period the state strived for pieces that the common workingman could understand and take pride in, while the rare number independently produced without state involvement tended to be criticized or censored by the state for reactionary tendencies.

Jazz and Rise of Country Music

In the 1920s country music is believed to have first originated in the southeast United Commonwealth, taking inspiration from pre-war popular music, folk music, and the music of the Appalachians. Country music is often dated to have begun with the "first generation" of the 1920s, which saw traveling fiddlers such as Gid Tanner become regional sensations in the country's south. Recordings were rare during this period and the phenomenon largely grew through traveling musicians who performed shows in theatres in cities such as New York City. One such musician, Fiddlin' Riley Carson, became one of the first country artists to be recorded around 1927. Although the record industry remained nearly nonexistent in the country, the rise of public radio spread the genre across the country, and "barn dance" shows featuring country music appeared in the south and a handful of northern urban centers. Many of these early country stars also performed blues numbers or collaborated with artists from other genres. At the end of the 1920s government support for Landonist realism and traditional continental music lead to state interest in the burgeoning country genre, as it seemingly combined and represented the "musical traditions of proletariat".

Concurrently, the emergence of African-led genres such as blues and jazz worried many conservative, white inhabitants in the United Commonwealth, and the Central Congress was little exception. This was further compounded by the Depression of 1931–1934, in which underground jazz shows and dances began to captivate much of the nation. The rapid industrialization and rebuilding of the nation throughout the 1920s had brought urbanizing influences to millions, and had attracted poor black workers to the cities, the epicenter of these new musical movements. Secretary of Culture Coleman Mueller remarked that the modern city was a "pestiferous growth" and contrasted the "unnatural", "twisted", and "cooped up" lives of urban inhabitants with the traditional agrarian lifestyle that offered a life of "sterling honesty". According to Mueller, the nation's cultural problems stemmed from alcohol, tobacco use, and premarital sex, which ran rampant in the overcrowded cities and communities of racial minorities and "foreigners". As reprinted in the Chicago-based newspaper Voice of Labor in 1937, Mueller blamed the "international Jew" that dominated Hollywood and other reactionary epicenters for undermining Continental values with the proliferation of jazz recordings. At the helm of the Department of Culture, Mueller reigned in the influences of African music by uplifting country music and other rivals as an alternative. He sought to deify and mythologize the traditional agrarian worker of America's past, that had been crushed by the monopolistic capitalists of pre-war America, a multi-year mission that took several forms.

In both music and film Mueller sough to promote a genre of collectivistic, agrarian, and traditional culture. He fought the popularity of promiscuous jazz dancing by mandating square dancing be taught in schools, and promoted public venues for round dancing and other group activities. State-pressed records and books for use in dance were widely distributed, while jazz artists failed to receive state funding for recording or distribution. Mueller's crowning achievement became the Grand Ole Opry, nationally broadcast country dance hall that brought country music to the forefront of every radio in the country. Jazz performances were banned from the top echelons of Continental theatre as "too unruly and uncivilized", and were heavily criticized in state papers as "pre-socialist and petty-bourgeois". Elsewhere the rise of jazz music as popular music in Sierra only seemed to confirm Mueller's fears. In the lead up to Great War I the Department of Culture cracked down on the illegal record trade, and tightened border security with Sierra. Mueller's successor, Joseph Barnes, would introduce the Barnes Code in 1934, which outright banned all depictions of illicit activities, uncontinental themes, promiscuity, and other taboos in all forms of film, music, and entertainment.

Music in Great War I

With the outbreak of the Great War in 1932, the national government dedicated all industry and resources toward the war effort. Effectively all of the nation's remaining entertainment industry was mobilized toward the creation of propaganda, with music focusing on patriotism and anti-entente rhetoric. Wartime music saw a resurgence of grand symphonic works, in a departure from the previous few years of relatively simplistic popular songs. This state-sponsored music would play a major role in boosting continental morale both at home and on the battlefield, especially as the United Commonwealth began to experience greater success. The war helped launch the radio industry in the United Commonwealth, originally as part of the war effort, but after the war this transferred over to civilian populations. By 1940, 92.6% of Northeastern American urban households would have a radio, while relatively poorer southern rural households still had one radio for every two households. Although it became common place for households to listen to the radio, interactions with radio stations were banned, as it was feared that foreign agents could use song requests on radio channels to send coded messages. Jazz music became at the center of the "cultural war", with the United Commonwealth banning the music. Rebellious continental children and teens would often meet in secret locations to listen to Sierran music stations playing jazz music, becoming a "religion worth fighting for" in the years after the Callahan era.

Compositions from past decades were re-recorded and pressed for the first time through the creation of V-Discs, a morale mission to send music exclusively to military personal. Toward the end of the war the United Commonwealth experimented in the creation of military bands, or groups that were formed to tour the country and reinvigorate morale in the home front. One such group was the Armstrong Ensemble, also known as the Continental Army Choir. Orchestral pieces such as "Fanfare for the Common Man" by Aaron Copland and choral anthems such as "The Sacred War" by Andy Armstrong were written during this time and became highly popular nationwide. The late 1930s and early 1940s also saw the United Commonwealth export continental music on the radio to neutral countries in Latin America, in an effort to combat the growing soft power of the Sierran entertainment industry and promote widespread continentalism. The South American Radio Wars of the 1940s and 1950s continued long after the war, as both Sierra and the United Commonwealth sponsored the creation of bands to tour the continent and promote their respective values.

As the war came to a close, the freedoms enjoyed by composers to experiment with new techniques were again curtailed, with newly appointed Department of Culture head Eric Johnston criticizing composers who had supposedly embraced non-continental ideals during the war. At Johnston's recommendation, government bureaucrat Joseph McCarthy was placed at the head of the Non-Continental Activities Committee, which ushered in a new era of censorship, investigation, and paranoia. McCarthy would begin a years-long investigation of creatives across the United Commonwealth, arresting hundreds of people for supposed capitalistic sympathies, and blacklisting others from ever receiving work in the industry. As a result, the decade from the end of the war to the death of Seamus Callahan in 1947 is largely seen as a dark age in Continental music. Under the harsh restrictions of McCarthyism, the younger generation largely strove to confirm, producing music that was bare in structure, or incorporated folk tunes. Other composers turned to film music work after the film industry saw a brief resurgence during the war. Jazz music largely diverged from the danceable popular music of the 1930s with the emergence of bebop as a more challenging "musician's music", although the genre failed to catch on in much of the United Commonwealth. The threat of investigation or arrest haunted several of the country's controversial non-conformist musicians, exemplified by the arrest Thelonious Monk in 1947. One of the few classical composers to thrive during this era would be Marc Blitzstein, who received renown for his 1939 Landonist musical The Cradle Will Rock.

The Gardner Thaw

After the death of Seamus Callahan in 1947, music in the United Commonwealth slowly experienced a laxing of restrictions and censorship. The early 1950s saw the rehabilitation of several prominent composers, as well as the return of pieces previously deemed unsuitable for public consumption. Musicians such as Leonard Bernstein were at the forefront of popular music of the era, and Bernstein conducted the world premiere of Charles Ives' Symphony No. 2, which had been written around a half century earlier but had been repressed throughout Ives' life. Although Gardner's policies yielded greater autonomy for Continental composers and musicians, the state's involvement in the production of music was not ended. Almost all recorded music during this era was filtered through the Musician's Guild, which rarely allowed the publication of musicians deemed unorthodox or unpatriotic. Officially the organization remained opposed to all modernist composition techniques, such as atonal harmony or serialism, for example the works of Arnold Schoeberg and Anton Webern were prohibited from music education until the 1960s in the nation's conservatories, and did not enter use until at least a decade after that. Works such as the Song for the Fortieth Anniversary of the Revolution romanticized Landonist ideology and the Revolutionary War—a prototypical landonist realist composition. The late George Gershwin, who had fell out of favor in the late 1920s for his involvement in the development of jazz music, was re-established a preeminent Continentalist composer during the Gardner era, with many of his compositions becoming popular standards.

The Gardner era also saw a new generation of "unofficial" music in a similar vein go the early Continental avant-garde. Composers such as Henry Cowell emerged among a group of musicians expelled from the nation's academies for their unorthodox styles of composition. Cowell's work eventually inspired others to rebel against mainstream Continental music, and they became incorporating previously illegal themes and ideas into their music. Although relatively underground, Cowell and his peers would be publicly denounced by the government in 1975 in a public address to the Musician's Guild, and similar attacks in state newspapers followed. Despite reticule politically, the Continental Avant-Garde only continued to grow domestically and abroad, culminating in a famous 1983 performance of experimental music at Carnegie Hall, the first such concert in New York City in some 55 years. From that point onward the nation's experimental composers became begrudgedly accepted in the Continental musical establishment.

In popular music Continental Jazz eventually developed a niche within Gardner era laxed restrictions. The 1940s had seen a large number of jazz bands disbanded, and those that remained often avoided labeling themselves as such. The 1950s also saw the rise of underground jazz journals and records disseminated among the music listening community. In response to the rising popularity of Sierran-style singers such as Frank Sinatra, the United Commonwealth supported "Stage Music", a genre of popular music involving solo singers with good vocal prowess, clear and catching vocal melodies, and symphony orchestra backing. Subject to Continental censorship, these songs were almost always written by a small group of composers at the head of the Musician's Guild, but nonetheless the performers employed to perform these songs reached new heights of popularity across the nation.

Manhattan Music and Rock

The United Commonwealth music landscape completely changed with the introduction of the Manhattan Island Exclusive Economic Zone in 1947. For the first time since the revolution, free market capitalism was reintroduced to Manhattan, granting the island the ability to operate almost entirely outside the United Commonwealth's economic codes, labor laws, and institutions. Already one of the centers of the nation's music industry, Manhattan would come to hold an almost complete monopoly over the music industry in later decades through its concentration of record labels and music-related corporations. Perhaps the most famous record label in the country, Atlantic Records, would be founded that year, growing to become one of the paramounts of the industry. The 1940s would see corporations such as Atlantic Records go to war against the Musician's Guild and other guilds and cooperatives that had strong roots in the city. Despite the Musician's Guild prohibition against Atlantic Records, which disallowed any Continentalist songwriter, producer, or musician from working with them, Atlantic slowly grew through the expertise of disavowed musicians, immigrants, and jazz musicians who steadily emerged from the New York underground into the limelight. Atlantic narrowly avoided being competed out of existence during its formative years, despite debilitating bans and censorship nearly bringing it to bankruptcy.

Manhattan came to encapsulate its own microcosmic music industry, complete with its own companies, songwriters, and manufacturers, which came to compete against the rest of the nation and even abroad. The Manhattan recording industry would become a powerhouse of Continental music, and the first city to allow widespread export and import of music recordings to and from other countries. A series of hits in 1949 and 1950, such as "Drinking Wine, Spo-Dee-O-Dee" by Stick McGhee and Jim Morris' "Anytime, Anyplace, Anywhere" helped Atlantic to stay afloat, and also introduced the world to the "Manhattan Sound". Around this time repression of jazz music also began to be relaxed, especially in New York, leading to a bebop renaissance in the city led by the likes of Fats Navarro and Dizzy Gillespie. Manhattan would witness the first sanctioned foreign performances in the city around 1950, which later paved the way for future bands from Sierra to tour Manhattan and then the rest of the country.

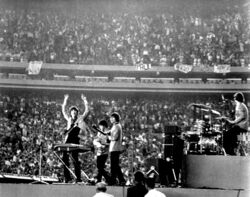

The first foreign groups in the United Commonwealth were allowed after 1961, with the Sierran band The Landing being the first to cross the Iron Curtain. Previously the most popular band in Sierra, the Landing's arrival in the United Commonwealth was met with heavy fanfare, and they quickly grew to the biggest band in the continent, and then the world. Despite initial attempts to limit the band's exposure in the country, later that year they played their most famous television performance on UC National Broadcasting, which launched them into stardom. They would go on to play Carnegie Hall and a series of other important venues before returning to Sierra. During Great War II, the Landing would be contracted for a morale-boosting position as military entertainment. On 30 September 1962 the group would perform a famous free concert at the newly built Aeneas Stadium in New York, as part of a show of joint Sierran-United Commonwealth cooperation. The show would become one of the largest in the Landing’s early history, although they later expressed annoyance at being unable to hear their own music over the roar of the crowd. IN 1964 Keith Winston began making general anti-war statements in public, causing the band to come under fire. After band manager Mick Bowie joined his friend in open criticism for the war and government policies, Bowie spent a short duration in jail, and the group began to be monitored by the Royal Intelligence Agency, and were also censored in the United Commonwealth until the end of the war. Two of the group’s films in production, including a government-backed propaganda piece, were canceled due to the stubbornness or contempt of the band members. According to Mitch Richards, during this time the band would claim to be conscientious objectors on religious grounds, although in March 1965 the band was criticized after Winston remarked, "Christianity will go. It will vanish and shrink. I needn't argue about that; I'm right and I will be proved right ... Jesus was alright but his disciples were thick and ordinary. It's them twisting it that ruins it for me." The group received condemnation from the continent’s conservative Bible Belt region, as well as the Vatican and many national broadcasting agencies.

The United Commonwealth's brief foray into alliance with Sierra made interest in Sierran musical styles impossible to contain. Bands such as the Landing were among the first foreign acts to have mass produced records in the United Commonwealth. Worried of the influence of the Landing and seeking to combat their ubiquity, the United Commonwealth commissioned a number of domestic bands to mimic their style and promote the country rather than Sierra. The most blatant of these bands would be The Stellars, an artificially constructed band by the Musician's Guild which sought to perfectly copy the Landing's style, leading to a national rivalry. Sierran rock music disseminated across the country, and a number of domestic groups followed. Notably, many classically trained musicians employed by the Musician's Guild formed rock bands of their own, creating the first uniquely Continental genre of rock music that tended to be far more progressive, symphonic, and complex compared to mainstream rock music. Known as the VI (vocal-instrument) bands, these officially recognized bands were granted an official artistic director by the state, who would serve as the band's manager, producer, and supervisor, but also sometimes joined the band in writing and performance. Late 1960s VI rock bands developed a youth-oriented, but state sanctioned sound that became popular across Continental radio. By the end of the decade many of the nation's VI bands had begun to push the boundaries of what was typically allowed, although across the board all music was required to be "family-friendly" and positive of Continental culture.

Manhattan remained at the epicenter of Continental music, attracting a number of foreign artists as well to stay in the city's artist havens and record music. Perhaps the most famous long term musical resident of the city would be Superian Bob Dylan, who stayed in the city throughout the mid 1960s before facing legal issues and ultimately being reported. Later Keith Winston of The Landing would make the city his home for a year in 1974, before his untimely death the following year. The United Commonwealth would also be home to the Woodstock Rock Festival of 1969, which would become the most famous festival in rock history, attracting some 500,000 people to the concert over the course of a long weekend, and would become one of the defining moments of the counterculture generation.

Alongside the state-sanctioned rock bands of the 1960s, a counterculture emerged that preached pacifism and the end to tyrannical government policies in the wake of Great War II. Whereas the government had tolerated the earlier protest songs of the 1920s, which promoted labor activism primarily, the 1960s spawned a generation of controversial, antiestablishment protest songs, which challenged the nation's government. Musicians such as Bob Dylan and the United Commonwealth's own Joan Baez wrote unsanctioned songs which shed light on taboo topics, the civil rights movement, and problems persisting within the nation. The popularity of folk songs that criticized the Vietnam War and other foreign conflicts polarized the Continental people, and brought about harsh retaliation from police and government officials. 1968 would become one of the most turbulent years in recent memory for the United Commonwealth, as antiwar protests and clashes with police escalated. In what became known as the "Bloody Summer", the United Commonwealth intensified its crackdown against antiestablishment dissidents. That July the pro-democracy March on Warrensville would be broken up by the Continental Revolutionary Army, resulting in dozens of deaths and many more arrests.