Cinema of the United Commonwealth

| Cinema of the United Commonwealth | |

|---|---|

Metropolia, New York City’s largest entertainment complex | |

| No. of screens | 25,189 (2017) |

| Main distributors | |

| Produced feature films (2016) | |

| Fictional | 109 |

| Animated | 22 |

| Number of admissions (2017) | |

| Total | 784,942,000 |

| • Per capita | 3.13 |

| Gross box office (2017) | |

| Total | $1.46 billion |

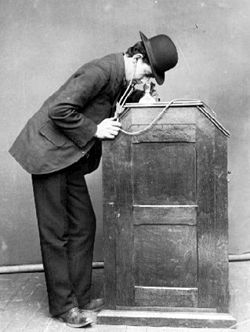

The cinema of the United Commonwealth includes films produced in the United Commonwealth and its constituent republics, and has had a major effect on the film industry in general since the early 20th century. Prior to the Continental Revolutionary War, the United Commonwealth was a center of the early film industry. Eadweard Muybridge became the first to demonstrate photography’s use in capturing motion in 1878, and in 1894 the world’s first commercial motion-picture exhibition was hosted by Thomas Edison and his Kinetoscope in New York City. The American east coast became highly competitive with the film industries of France – credited with having begun the medium under Auguste and Louis Lumière – Italy, and Germany, however, the highly monopolistic practices of the American film companies spurred a westward migration of film producers and creatives, primarily to Sierra, birthing the industry giant of Hollywood. The 1915 D. W. Griffith film The Birth of a Nation became a landmark in film history, albeit showcasing the negative aspects of pre-continental culture in North America.

The Continental Revolution posed a complete upheaval of the entertainment industry in the United Commonwealth. The 1920s saw an explosion in creativity among Continental film producers inspired by revolutionary ideas, although the nation’s film industry became fully nationalized by the Continentalist Party, which became the guiding force on the industry thereafter. The United Commonwealth fell behind Sierra in terms of cultural exports by the 1930s; the development of the monopolistic Studio system, the vertical integration of the industry, and the compulsively consumerist nature of Hollywood proved lucrative but was rebuked by the Continentalist Party. In 1927 the “Iron Curtain” formally descended, and Sierran-made entertainment was banned from the country. In its place the United Commonwealth cultivated and promoted the Landonist realism genre, characterized by its depictions of Landonist values and symbols, the emancipation of the proletariat, and the greatness of the Continental states. Under the leadership of Seamus Callahan (1923–1947) the nation’s film industry experienced harsh censorship and government oversight. Nonetheless this era produced numerous groundbreaking films, such as Battleship Kentucky (1924), Greed (1926), Metropolis (1927), and Mr. Smith Goes to Chicago (1939).

The death of Callahan in 1947 and the process of Decallahanization undertaken by such leaders as Rupert Gardner revitalized the nation’s film industry, allowing filmmakers a margin of comfort to expand past the boundaries of Landonist realism. As compared to their Sierran counterparts, Continental filmmakers often created films that were more culture-specific and unrelatable to wider audiences, and they most often sought artistic success over that of financial success, due to government funding regardless of performance, as long as directors remained in the good graces of the party. Continental-backed western films, usually filmed in allied Italy, known as “Red Westerns” or “Spaghetti Westerns" directly competed with the Sierran-led Western genre. The 1960s saw the lessening of restrictions on foreign imports to the country, causing a boom in creative pursuits; the symbiotic relationship and competition between the rivals of Sierra and the United Commonwealth is credited as a factor in the rise of New Hollywood. Films such as Dr. Strangelove (1964) and The Manchurian Candidate (1966) spoke to the population’s Cold War-era fears, while films such as Lunaris (1967) built on interest in the Space Race and futuristic optimism, revolutionizing the science fiction genre. Beginning in the 1960s the Continental film industry was transformed by the rise of numerous film cooperatives and limited corporation-involvement from the Manhattan Island Exclusive Economic Zone.

History

Origins (1889–1917)

The North American film industry began in 1877 when Eadweard Muybridge, capturing running horses in Palo Alto, Sierra, produced a series of photographs reproducing motion. This inspired interest among inventors to create devices capable of reproducing this effect, the most successful of which being Thomas Edison’s kinetoscope, first produced in 1889. This is considered the birth of the film industry in the United Commonwealth, with the town of Fort Lee, New Jersey, just outside New York City and home to Edison’s studios, becoming the motion-picture capital of Anglo-America. Edison’s Black Maria Studio, established in 1893, is considered the world’s first production studio. Soon other studios followed, many of which taking advantage of cheap real estate prices in the Palisades as well as the booming population of New York proper. Fort Lee became the home of other early film giants, such as Kalem Company in 1907, Champion Film Company in 1909, and numerous others. Performers such as W. C. Fields and the Marx Brothers, as well as the growing vaudeville and broadway scenes of New York, were popular additions to early American films.

Many early filmakers, especially Edison, benefited from the monopolistic practices of the late, pre-Continental United Commonwealth and its patent laws, stamping out many minor studios that emerged in the 1910s. However, this also led to many filmmakers fleeing outside the confines of Edison and his lawyers, most notably to Sierra. By 1912 the lax patent laws of the Southwest Corridor and its favorable year-round weather led to Porciúncula rivaling the New York region as the center of the continent’s film industry.

Other companies, such as Kalem Company, pioneered filming in Jacksonville, Florida, which became the “Winter Film Capital of the World” due to its warm climate, excellent rail service, exotic locations, and cheap labor. In 1917 the first feature-length color movie produced in North America, The Gulf Between, would be filmed in Jacksonville. Nonetheless, the United Commonwealth’s film industry continued to boom up to the Continental Revolutionary War. Manhattan nickelodeons – the first indoor exhibition spaces dedicated to showing projected motion pictures – became shorthand for films as a whole worldwide.

The United Commonwealth also competed with the film industries of European nations. Considered the birthplace of film, France maintained one of the largest and most dominant film industries up to the Great War, followed closely by the United Kingdom, Germany, and Italy. Companies such as Kleine Optical Company and Pathé found great success importing European films to American audiences. Although largely produced outside the United Commonwealth, The Birth of a Nation directed by D. W. Griffith was released in 1915 to immense public reception. Lauded for its technical virtuosity, length, and production, the film would become one of the first true film epics. The film is also famous for its highly racist story and portrayal of African-Americans, leading to it becoming highly controversial and the target of the emerging NAACP. Continental historians would later regard the film as a key symbol in the decadence, revisionism, and amorality of the pre-continental government—the film was shown in the Federalist capitol and helped to spark a reemergence of the Ku Klux Klan, which terrorized the United Commonwealth for decades to come.

Revolutionary Era (1920s)

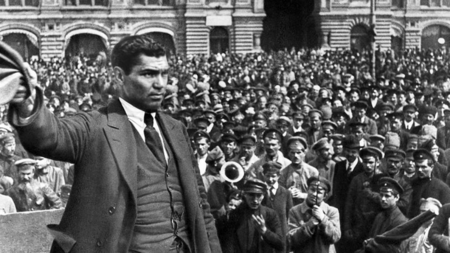

The outbreak of the Continental Revolutionary War gradually brought the nation’s film industry to destruction. As mobilization began by the Federalist government, the film industry largely shut down temporarily, and later military devastation made the start up of the major film studios nearly impossible. Many of the largest film studios that remained in the country fled to Sierra, including the New York-based Famous Players-Lasky. Much like the music industry, the film industry became partially hijacked by the politics of both sides of the revolution, with patriotic and propagandic films becoming popular. Films such as 1918’s Joan of Plattsburg sought to promote enlistment and a sense of duty to repulse the Continentalists. Initially many Americans held a romantic view of war due to the relative lack of radio coverage reporting the conditions of the conflict, however, as the conflict came to encompass the entire country and bring battle to the doorstep of many Americans, this romantic sentiment quickly changed. Of the few films released toward the end of the war, many encompassed a more nihilistic outlook, such as The Man That Might Have Been (1920), which depicts the life of a father had his son not died in the conflict. The Continentalist Party, spurred on by Zhou Xinyue, quickly realized the power of state-created films and music for the masses as a propagandist tool, later inspiring the founding of Public Broadcasting Service, a multi-media broadcasting service that exists to this day. In 1919 Aeneas Warren ordered the nation’s film industry nationalized, and film production and distribution became solely under the purview of the People’s Commissariat for Education for the remainder of the war.

While the pre-war conditions of the United Commonwealth had begun the mass exodus of filmmakers, producers, and creatives out of the country, the war and the nation’s post-war conditions completed it. Another wave of migration came during the war and immediately after it, as creatives and people of all walks of life fled the destructive conflict or the unstable regime destined to follow. This had an immediate effect of a creative brain drain in the fledgling United Commonwealth, which left the film industry in a precarious position. The remaining entertainment conglomerates that hadn't fled the country suffered bankruptcy or state-inflicted dismantling, as the film industry was considered a prime example of the exorbitant greed of capitalism and the producers of nonessential, manipulative goods. Much like music, films became the subject of ridicule and censorship as emblematic of the problems of the Weeping Twenties, leading to select films being targeted in national book burning campaigns. In 1923 Seamus Callahan came into power as the country's paramount leader, expanding Kentucky Bend and other re-education camps across the country, and within the next five years the country's old entertainment industry became essentially dismantled, as capitalists, business magnates, and industrialists were arrested, brought to these camps, or killed. On 8 April 1924 the Central Committee issued the "Action against the Reactionary Spirit", which called for numerous films, books, records, and other works of art that portrayed or celebrated capitalism, nationalism, or other reactionary ideals to be destroyed. Although not all films were labeled as such, the film industry as a whole was looked upon by many as a purely capitalistic and exploitative industry, in stark contrast to the less financially prohibitive theatre which catered to the pre-war proletariat, and as such many carried out the willful destruction of films and music records and other symbols of the industry with zeal. This destruction, as well as a lack of archiving worldwide and the habitual reusing of film stock, has led to an estimated 90% of all films produced before 1928 being considered lost.

The Continental film industry began to rebuild despite these setbacks. In 1920 the First State School of Cinematography was established in New York City by decree of Aeneas Warren, and later that year the Continental Photography and Motion Picture Department, later reorganized into the State Committee for Cinematography after 1923, was founded as the overseer of state films. The nation’s cinemas became home to newsreels and propaganda films, and short films were produced championing and explaining the causes of Landonism. Initially censorship was lax, however, the creation of films outside the state's purview became exceedingly difficult from 1922 to 1928, when the National Board for Industrialization and Cooperation (NBIC) was designated as the sole operator of the economy. In 1924 the state-sponsored Central Documentaries was created, which revolutionized the documentary and newsreel format, creating experimental non-fiction works, propagandized depictions of Continental life, and informative looks into the Continentalists. In 1926 the Public Broadcasting Service was founded as a state-sponsored broadcasting organization, and later evolved into creating television shows and films, the latter primarily under the PBS Films division.

Despite later censorship, the mid to late 1920s in the United Commonwealth is often regarded as one of the most experimental and trailblazing eras in cinema. Inspired by the revolutionary fervor brought on by the Continentalists and the upheaval of old cultural norms, filmmakers took to film numerous works exploring new topics and techniques. The Continental Futurism movement saw creatives who rejected the ideals of the past, academies, and urbanism, and celebrated modernism, cultural rejuvenation, industry, and youth. Others created works questioning America’s past fascinations with consumerist culture, criticizing popular film, Hollywood, and advertising. Period epics and popular genres of the 1910s were rejected as art came to reflect society’s doubt toward the beliefs and institutions of the pre-revolution. The traumatic events of recent times altered basic assumptions, and America's perceived ascendancy as a continent exceptional from the rest was shattered; the advancements of the 19th century had not made war unviable as previously hoped, nor did American institutions safeguard the Continental people from corruption, wealth inequality, or squalor. Realistic depictions of the world seemed inadequate to describe this sense of trauma or the horrors of the war felt directly by the nation, and popular art of the early 20th century diverged toward that of the surreal, morally ambiguous, or nihilistic.

Filmmakers such as Man Ray became on the forefront of the surrealist movement, with works such as the 1923 film A Return to Reason. The idea of Montage Theory, or the idea that films rely on editing and can create symbolism through cuts was coined and pioneered in the 1920s United Commonwealth. Films such as the 1924 Battleship Kentucky became major hits and showcased emerging editing techniques to the larger world for the first time. The movie, which centers around a rebellion against the Federalist government, is often regarded as the first film to cut between shots to create metaphorical meaning and communication, and won its creators world-wide fame. The film was followed by Fall of the Oligarchs that same year, which repurposed pre-war documents and clips to juxtapose newly filmed sections. In 1925, Ralph Steiner (director of Battleship Kentucky) and numerous other popular directors would found the Association of Revolutionary Cinematography (ARC), considered the nation’s first cooperative to “meet the ideological and artistic needs of the proletariat”. Film topics of the time most often included negative portrayals of the pre-war government, the exceptionalism and heroism of the Landonists, or famous events in American history, however, the 1920s also saw the release of films dealing with the difficulties of contemporary life, something that would be prohibited only a decade later. The 1926 Sierran-filmed Greed became a popular psychological drama with themes that could be approved of by Continental censors.

In 1927 the film Metropolis was released, becoming a pioneering science-fiction film and the first feature-length movie in the genre. The film depicts a dystopian futuristic society in which the workers topple a greedy oligarchy, receiving praise from the Continentalist Party and criticism from foreign viewers. In 1929 the influential and experimental documentary Man with a Movie Camera was released. The film would pioneer a number of cinematic techniques, including multiple exposure, fast and slow motion, freeze frames, match cuts, jump cuts, tracking shots, extreme close-ups, reversed footage, split screens, and numerous other visual techniques. Although criticized for its focus on form over content, the film would later be voted one of the greatest films ever made, and the best documentary of all time by the British Film Institute.

Landonist Realism, Iron Curtain (1930s–1940s)

The import of Sierran media remained denounced but prevalent all throughout the 1920s in Continental cinemas, and Sierran films also personally catered to the nation’s elite, causing alarm among the upper Continentalist Party once Seamus Callahan had firmly come to power. Sierran entertainment became labeled as promoting "bourgeois principles", which sought to undermine the fledgling Landonist government. As such, in 1927 the National People's Congress passed legislation to completely cut connections to Sierra and the rest of the "reactionary world", and banned all Sierran-made films on the grounds that they were antithetical to Landonist values, officially beginning the “Iron Curtain”. By the end of the decade, state-sponsored censorship of film and the arts intensified, to dismantle any last vestiges of reactionary, capitalistic, or foreign ideals in the United Commonwealth. Instead the nation’s People's Commissariat for Culture (created in 1924) sought to develop a unique, pro-Continentalist form of art known as Landonist Socialism, which depicted Landonist values and symbols (called "Landonography"), the emancipation of the proletariat, and the ascendancy of the new government triumphing over the non-Continentalist powers. Filmmakers who sought to make films outside this norm found themselves unable to secure funding, with their releases heavily scrutinized or censored, and those that heavily diverted from the government-issued policies could face imprisonment. Films were required to be submitted to a handful of organizations for approval; the largest cooperatives and film studios self censored and worked together to create codes of ethics to prevent government involvement.

As an important part of the Landonist realism paradigm, Continental films of the era primarily focused on everyday people and Continental folkheros, such as the railwayman John Henry (as seen in the 1929 film Steal-Driving Man), the lumberjack Paul Bunyan, Captain Stormalong, and Casey Jones (as in the 1930 film The Ballad of Casey Jones, based on the traditional song of the same name). THe heroes of these films usually displayed a close connection to the masses, with their folk wisdom being contrasted with self-centered villains, who were directly a part of or in reference to the bourgeoise. Films such as Commonwealth of Toil sought to reinterpret the traditional holiday pf Thanksgiving, demphasizing the religious-based settler-colonialism of the early American settlers, and instead imagining Thanksgiving as a coming together by indigenous peoples and Plymouth's workers for mutual cooperation.

Also popular, especially in the lead-up to the Great War and after its outbreak, were war films which exemplified Continental bravery and the revolution, while often displaying Sierra as imperialistic if referenced. This was especially the case in the 1932 film Glory, directed by Ralph Steiner. The nationalistic historical drama, based on a daring defense of the United Commonwealth against western invaders, made clear reference to contemporary Sierra, suggesting that the United Commonwealth would need to come together to repulse any such invasion in the future. The film would be rapidly completed in light of rising world tensions, being released two months before the eventual outbreak of the Great War. Also among these war films were Butler (1930), which depicted the romanticized bravery of famous soldier Smedley Butler in the revolution, January (1931), depicting the early days of the revolution, and Birth of a People (1939), which sought to counteract the propaganda of The Birth of a Nation with its own anti-Lost Cause, anti-Klan propagandizing. January would become a hit movie across the country, and would be declared the nation's first Best Picture.

Silent films fell out of fashion after the release of the Sierran film The Jazz Singer in 1927, and “talkies” soon caught on in the United Commonwealth at the end of the decade. This brought about the end of the careers of many 1920s actors who could not compete in the sound era, and the rising success of new stars. In the lead up to the Great War, the People's Commissariat for Culture cracked down on the illegal media trade, tightened border security with Sierra, and in 1932, Joseph Barnes introduced the Barnes Code, which outright banned all depictions of illicit activities, uncontinental themes, promiscuity, and other taboos in all forms of film, music, and entertainment. The Barnes Code and war-time restrictions led to another wave of government intervention in film. All existing cooperatives, autonomous studios, and distribution networks allowed to flourish in the 1920s became centralized under the planning agency of the State Committee for Cinematography.

This led to a temporary period during the latter half of Seamus Callahan’s life where essentially all films made in the country were ordered at the discretion of the government, subject to script revision and oversight in an expanding bureaucracy, and sometimes full-scale censorship. Often films would begin production only to be arbitrarily canceled months later due to a problem discovered by the state committee. This oversight greatly slowed down production and inhibited creativity, leading to a steady decrease in the number of films produced each year into the 1940s. The industry saw its numbers drop from over 100 films a year in 1930, to 70 a year in 1936, to 30 a year in 1939. Many early directors retired during this period, while those such as Ralph Steiner saw their output restricted. Steiner would release only one film between 1940 and 1947, despite working on a total of four, which was released as 1944’s Johnny Appleseed. The 1930s saw the Continental film industry become completely self-reliant as part of Callahan’s massive industrial buildup. A proprietary sound system was unveiled in 1930, after which point the licensing of Sierran technology to create talkies was banned.

Films in the latter half of Callahan’s reign firmly abandoned the avant garde, creating films meant to appeal to the masses. The SCC championed a “cinema of the millions”, which used clear, linear narration in stark contrast to the surrealist or non-linear storylines of previous films. Continuity editing and steady storytelling became the norm, usually espousing lessons in good citizenship or party doctrine. Films during this era are often criticized as a result as being “formulaic”, and appealed to a limited audience outside the country due to their niche and culturally Continental subject matter. Nonetheless, movies such as Cinncinnatus (1936) and Cinderella (1940) remain standout films. The 1940s also saw the use of the film industry to tailor to a cult of personality around Seamus Callahan, with numerous films being produced depicting the leader in a triumphal light. Actors such as Keith Brosnan, famous for his portrayals of the leader after his breakout role in January, saw the rise and fall of their careers based on the production of pro-Callahan propaganda and war films. The last years of the Great War saw the film industry reach its low point. In addition to dealing with the severe losses brought about by war, whether that be physical losses, a lack of funding, or extreme censorship and government oversight, the government approval of films dramatically declined. Compared to the Sierran market where the Golden Age of Hollywood was underway, with hundreds of films were being produced each year, the Continental market was in sharp decline.

At the start of the 1940s a number of theatre productions, operas, and documentaries filled large portions of the government’s allotments for films, with very few non-fiction, original stories being produced. A notable exception being the highly praised fictional drama Mr. Smith Goes to Chicago, which became 1939's Best Picture. The demand for new content was met by post-war propaganda and “Trophy Films”, or looted foreign films from the war, sometimes illegally played, other times with limited or no government approval. Many of these films shown did not meet the production standards of a regular Continental film, however, historians hypothesize that the government laxed restrictions due to the propagandic value of watching captured film and to revitalize the film industry, and additionally some foreign films had parts removed by censors before reissuing. Seeking to improve on this domestic shortcoming, in 1940, the new head of the SCC’s Dramatics Cultivation Committee, Frank Stauffacher, argued that Continental films would need to expand outside the bounds of tight restrictions in order to remain artistically viable and competitive against the west. Although the government remained skeptical, Oehler recruited among Chicago and New York’s theatre scenes in the hopes of attracting new creative talent.

His crowning achievement would be the 1941 film Citizen Kane, which although not highly regarded in its time, has since been praised as one of the greatest films of all time, and a rare gem in the Continental films of the era. The late 1940s also saw successful adaptations of Continental literature, such as 1943's For Whom the Bell Tolls and 1945's The Last of the Mohicans, as well the first color films, such as Robin Hood (1946). Stauffacher would establish the “Art in Cinema” program at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City, which popularized “alternative film techniques” and inspired experimental animation. It was during this period that experimental stereoscopic films – a precursor to 3D cinema – were developed in the United Commonwealth, later becoming a popular marketing gimmick in Sierra after the rise of television.

Gardner Thaw, New Cinema (1950s–1970s)

With the death of Seamus Callahan in 1947, restrictions in the arts and censorship were relaxed, breathing new life into the entertainment industry. The end of the decade saw the reintroduction of several older films into the mainstream which had been censored during the Callahan government, including foreign films. Especially under Rupert Gardner a period of relaxed tensions with Sierra and its allies began, including the piecemeal introduction of foreign media for the first time since the beginning of the Iron Curtain. Books, music, and films from Sierra and other nations received approval for distribution, and in the film industry the government granted filmmakers the margin of comfort needed to move away from Landonist realism. The genre was deemed too narrow for experimentation, and with the introduction of Hollywood media to Continental markets, tastes had moved on to more entertaining and artistic Continental films. Similarly, the introduction of television began to threaten the hold that film held over entertainment. This provoked a number of responses, including the funding of high-cost historical epics and musicals which could outdo television and foreign media. Elsewhere Continental filmmakers differentiated themselves through intricate themes, writing, and experimentation.

The relaxing of restrictions, the emergence of interconnectedness and rivalry between Continental and Sierran media, and a new generation of filmmakers led to creative booms in both countries. In the United Commonwealth emerged the “Continental New Cinema”, a movement that rejected traditional filmmaking conventions, exploring new approaches to narrative, editing, and visual style. Influenced by the documentary style of their forebears and with limited funding and equipment, films such as Little Fugitive (1953) used nonprofessional actors and a naturalistic form of storytelling. Due to the financially draining nature of the war on cinema and the rediscovery of old, foreign films, mainstream cinema fell back on largely classic tropes and plain narratives, which the members of the New Cinema wholesale rejected. From this rebellious nature was birthed films such as Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome (1954), Anticipation of the Night (1958), and To Be Alive! (1962), which became unexpected successes and received international recognition. The Structural genre emerged in the early 1960s, characterized by simplifying the techniques pioneered by New Cinema and emphasizing the structure of film in production, often through the use of fixed camera position, flicker effects, loop printing, and rephotography.

The Manhattan Island Exclusive Economic Zone opened in 1947 as an experiment in government-regulated capitalism within a limited space, and soon the island became the capital of the Continental film industry. Numerous foreign-inspired film companies emerged during the 1950s centered in the city, as did foreign film distributors. The Manhattan studios would popularize technical innovations from other countries, such as technicolor, stereo sound, and widescreen. Many early Manhattan films sought to capitalize on the popular films and genres of Sierra, leading to numerous adaptations and imitations. Taking advantage of the talent of the city’s popular Broadway theatre, the musical West Side Story (1960), with music by Leonard Bernstein, became a major hit film. Historical epics also became a popular genre out of Manhattan, often requiring huge casts and multiple locations to film. Doctor Hidalgo (1965) would depict the life of a physician during the Continental Revolutionary War, while other films sought to depict the “Great American Novel” adapted to the screen. Such examples include The Great Gatsby (1959), To Kill a Mockingbird (1962), The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1964), The Last of the Mohicans (1968), Moby Dick (1970). 1968’s Ten Days That Shook the World, a multi-part epic about the history of the country, would become the most expensive film to make in the country’s history. Encouraged by the New Frontier of Lysander Hughes, the 1950s saw the rise of science fiction epics such as The Day the Earth Stood Still.

In Sierra the “Golden Age of the Western” reigned from the 1930s to the 1960s, taking advantage of the country’s vast landscapes and history as the “Wild West”. Seeking to compete with the Sierran monopoly, the Spaghetti Western subgenre emerged led by Continental filmmakers. Lacking suitable locations for westerns, the genre is named for the fact that Continental filmmakers turned to allied Italy for on-location filming and talent, cultivating a partnership between the two nations’ film industries. Films such as A Fistful of Dollars (1961) and The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1964) became highly successful westerns that rivaled even the Sierran classics. Others such as A Bullet for the General (1966) and Django (1968) depicted stories of revolutionaries fighting against corruption and the rich, although the latter’s high degree of violence limited its appeal across borders. Spaghetti Westerns would remain popular throughout the 1960s and early 1970s, although by the end of the decade they had lost their following among mainstream audiences and production diminished.

The Manhattan-centered company of Filmexport arose in 1957, seeking to capitalize on the growing popularity of Continental films abroad and distribute foreign films between countries. Additionally the era saw the country’s first awarding of the Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival, with 1958's The Cranes Are Flying. As foreign competition increased, films often spoke to the nation’s Cold War-era fears and anxieties, with such examples as Dr. Strangelove (1964) and The Manchurian Candidate (1966). Director Stanley Kramer would coin the term “message films" for the genre of films that shed light on taboo topics often repressed in other countries, such as combating racism, nuclear war, and the ills of society. He would also help spearhead the creation of the Chicago International Film Festival. Initially inspired as a Landonist alternative to the capitalist-dominated festivals, it is today considered one of the “Big Five” film festivals worldwide. Perhaps the most revered director of the decade, Perseus Seaton, gained widespread acclaim in the 1960s for science fiction movies such as The Giver (1962) and Lunaris (1967), and the sprawling historical epic Barry Lyndon (1974). Manhattan also became the birth of adult erotic films, as popularized by such films as Blue Movie (1969) by Andy Warhol. In 1967 the 50th anniversary of Continental cinema, from the nationalization of the industry by Aeneas Warren, was celebrated with the proclamation of Continental Cinema Day.

Awards

| Year | Cannes Palme d'Or |

Chicago | Sundance | Best Picture (Sierra) |

Best Picture (Continental) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1927 | Wings Dir. William A. Wellman |

||||

| 1928 | The Patriot Dir. Ernst Lubitsch |

||||

| 1929 | The Love Parade Dir. Ernst Lubitsch |

||||

| 1930 | All Quiet on the Western Front Dir. Lewis Milestone |

||||

| 1931 | Cimarron Dir. Wesley Ruggles |

January Dir. ??? | |||

| 1932 | Grand Hotel Dir. Edmund Goulding |

The Deserter Dir. ??? | |||

| 1933 |

Cavalcade |

Triumph of the People | |||

| 1934 |

Cleopatra |

Warren | |||

| 1935 |

Mutiny on the Bounty |

Seven Brave Men | |||

| 1936 |

Dodsworth |

Cinncinnatus | |||

| 1937 |

True Confession |

Cosmic Voyage | |||

| 1938 |

You Can't Take It with You |

John Brown | |||

| 1939 | Union Pacific Dir. Cecil B. DeMille |

Gone with the Wind |

Mr. Smith Goes to Chicago | ||

| 1940 | Gaslight Dir. Thorold Dickinson |

The Porciúncula Story |

Cinderella | ||

| 1941 | Blind Venus Vénus aveugle |

The Maltese Falcon |

Citizen Kane | ||

| 1942 |

The Song of Bernadette |

Casablanca |

The Pride of the Yankees | ||

| 1943 | María Candelaria Dir. Emilio Fernández |

Heaven Can Wait |

For Whom the Bell Tolls | ||

| 1944 | Torment Hets |

The Lost Weekend Dir. Billy Wilder |

The Man Behind the Mask | ||

| 1945 |

The Last Chance |

Mildred Pierce Dir. Henry King |

The Last of the Mohicans Dir. ??? | ||

| 1946 |

Men Without Wings |

It's a Wonderful Life Dir. Frank Capra |

A Stranger in Congress Dir. ??? | ||

| 1947 |

Antoine and Antoinette |

The Treasure of the Sierra Madre Dir. John Huston |

Miracle on 34th Street Dir. ??? | ||

| 1948 | Crossfire Dir. Adrian Scott |

The Red Shoes Dir. ??? | |||

| 1949 |

The Third Man |

All the King's Men Dir. Robert Rossen |

White Heat Dir. ??? | ||

| 1950 | Sunset Boulevard Dir. Billy Wilder |

Born Yesterday Dir. ??? |

Red Roy's Last Ride Dir. ??? | ||

| 1951 | Miss Julie Fröken Julie |

A Sierran in Paris Dir. Arthur Freed |

A Streetcar Named Desire Dir. Elia Kazan | ||

| 1952 | Two Cents Worth of Hope Due soldi di speranza |

Singin' in the Rain Dir. Stanley Donen |

The Day the Earth Stood Still Dir. ??? | ||

| 1953 | The Wages of Fear Le salaire de la peur |

From Here to Eternity Dir. Fred Zinnemann |

Roman Holiday Dir. ??? | ||

| 1954 | Rear Window Dir. ??? |

On the Waterfront Dir. Elia Kazan | |||

| 1955 | Marty Dir. Delbert Mann |

Marty Dir. Delbert Mann |

The Night of the Hunter Dir. ??? | ||

| 1956 | The Searchers Dir. John Ford |

Giant Dir. ??? | |||

| 1957 | The Seventh Seal |

The Bridge on the River Kwai Dir. David Lean |

Twelve Angry Men Dir. Sidney Lumet | ||

| 1958 |

The Cranes Are Flying |

Touch of Evil Dir. ??? |

Vertigo Dir. ??? | ||

| 1959 | Black Orpheus Orfu Negro |

Destiny of a Man |

Anatomy of a Murder Dir. Otto Preminger |

On the Beach | |

| 1960 | La Dolce Vita Dir. Federico Fellini |

The Apartment |

The Magnificent Seven Dir. John Sturges |

West Side Story | |

| 1961 | The Long Absence Une aussi longue absence |

The Naked Island |

The Hustler Dir. Robert Rossen |

Clear Skies | |

| 1962 |

The Exterminating Angel |

8½ Dir. Federico Fellini |

Lawrence of Arabia Dir. David Lean |

To Kill a Mockingbird | |

| 1963 |

High and Low |

The Great Escape Dir. John Sturges |

|||

| 1964 | My Fair Lady Dir. ??? |

Dr. Strangelove | |||

| 1965 |

Doctor Hidalgo | ||||

| 1966 | |||||

| 1967 | |||||

| 1968 |

Ten Days That Shook the World |

Ten Days That Shook the World | |||

| 1969 | |||||

| 1970 | MASH

Dir. Robert Altman |

El Topo |

Tora! Tora! Tora!

Dir. Richard Fleischer, Kinji Fukasaku, Toshio Masuda |

Moby Dick Dir. ??? | |

| 1971 | Fiddler on the Roof

Dir. Norman Jewison | ||||

| 1972 | |||||

| 1973 | |||||

| 1974 | |||||

| 1975 | |||||

| 1976 | |||||

| 1977 | |||||

| 1978 | |||||

| 1979 | |||||

| 1980 | |||||

| 1981 | |||||

| 1982 | |||||

| 1983 | |||||

| 1984 | |||||

| 1985 | |||||

| 1986 | |||||

| 1987 | |||||

| 1988 | |||||

| 1989 | |||||

| 1990 | |||||

| 1991 | |||||

| 1992 | |||||

| 1993 | |||||

| 1994 | |||||

| 1995 | |||||

| 1996 | |||||

| 1997 | |||||

| 1998 | |||||

| 1999 | |||||

| 2000 | |||||

| 2001 | |||||

| 2002 | |||||

| 2003 | |||||

| 2004 | |||||

| 2005 | |||||

| 2006 | |||||

| 2007 | |||||

| 2008 | |||||

| 2009 | |||||

| 2010 | |||||

| 2011 | |||||

| 2012 | |||||

| 2013 | |||||

| 2014 | |||||

| 2015 | |||||

| 2016 | |||||

| 2017 | |||||

| 2018 | |||||

| 2019 | |||||

| 2020 | |||||

| 2021 | |||||

| 2022 | Decision to Leave Dir. Park Chan-wook |

Aftersun Dir. Charlotte Wells |

The Fabelmans Dir. Robert Rosenberg |

Everything, Everywhere, All at Once Dir. The Daniels A24 | |