Germany

- "Germany" redirects here. For other uses, see Germany (disambiguation).

German Empire Deutsches Reich | |

|---|---|

|

Motto: Einigkeit und Recht und Freiheit | |

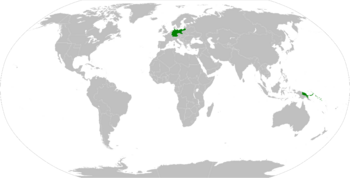

Location of Germany within Europe | |

Map of Germany and its states | |

| Capital |

Berlin (executive) |

| Largest city | Berlin |

| Official languages | German |

| Recognised regional languages | Danish · Low Saxon · Low Rhenish · Sorbian · Romany · North Frisian · Saterland Frisian |

| Demonym(s) | German |

| Government | Federal parliamentary Constitutional Monarchy |

• Emperor | Georg Friedrich |

| Karl Laschet (Z) | |

| Legislature | Parliament |

| Bundesrat | |

| Reichstag | |

| Formation | |

| 843 | |

| 962 | |

| 1701 | |

| 1848–1849 | |

| 4 April 1853 | |

| Area | |

• Total | 543,443.94 km2 (209,824.88 sq mi) |

| Population | |

• 2020 census | 116,759,741 |

| Currency | Deutsche mark (DEM) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

• Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Date format | dd-mm-yyyy |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +49 |

| ISO 3166 code | DE |

| Internet TLD | .de |

|

Website www.germany.de | |

Germany (German: Deutschland), officially the German Empire,[1] is a country in central Europe. It lies between the Baltic and North Seas to the north and the Alps to the south and is bordered by the Netherlands and France to the west, Switzerland and Austria to the south, Czechia to the southeast, Poland to the east, Lithuania to the northeast, and Denmark to the north. Germany also has two overseas territories, New Guinea and Qingdao, which border Indonesia and China, respectively. It has a population of 116.75 million people, making it the second most populous state in Europe after Russia and the most populous located entirely within Europe.

The northern part of modern Germany has been inhabited since classical antiquity by various Germanic tribes. The region has been referred to as Germania since before AD 100. Between the fourth and sixth century the Germanic tribes expanded southward, contributing to the collapse of the Western Roman Empire. In the 10th century German territories formed the core of the Holy Roman Empire and remained so until its dissolution in 1806. In the 16th century the territories of northern Germany became the center of the Protestant Reformation, which directly contributed to the Thirty Years' War. After the dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire and the Napoleonic Wars, the German Confederation was formed in 1815 as a replacement for the Holy Roman Empire. In 1848 the German Revolution began, as part of the larger Revolutions of 1848, which led to the establishment of the German National Assembly, the first unified parliament of its kind in Germany. As ruler of the largest and most influential state in the region, Wilhelm I of Prussia was able to shape the Frankfurt Parliament in his favor, accepting the title "Emperor of the Germans" in February 1849. The Schleswig War (1848–1849) with Denmark tested the new union and led to the inclusion of Holstein and southern Schleswig. However, this led to the Austro-German War (1851–1853), in which German state defended against Austria and Russia. German success in the conflict united the nation and helped develop a sense of national identity, while the Treaty of Vienna led to international recognition.

German is a federal constitutional monarchy and is a fairly decentralized country compared to other European nations, with sub-national kingdoms, duchies and principalities that are largely autonomous of the federal government in Berlin. It is a great power and a strong economy, and is a global leader in the scientific and technological sector. It is the second-largest economy in Europe after Russia and is the largest economy entirely within Europe. Considered to be a social democracy, Germany provides its citizens with universal healthcare, social security, tuition-free higher education. It also possesses one of the largest militaries in the world. Germany is a member of the League of Nations, the European Community, NATO, and the G20.

Etymology

The word Germany in English is derived from Latin Germania, a term that Julius Caesar adopted to referred to the people who lived east of the Rhine. It's possibly of Celtic origin, related to the Irish word Gair (neighbor). The German endonym Deutschland, originally diutisciu land (the German lands), is derived from deutsch (which shares the same root as Dutch). Deutsch is descended from the Old High German diutisc, meaning "of the people". The term was originally used to distinguish the common people's language from Latin and it's descendants. Diutisc is ultimately descended from Proto-Germanic þiudiskaz, also meaning of the people (which is where the Latin form Theodiscus is derived), derived from þeudō, descended from Proto-Indo-European tewtéh₂-, which is also the origin of the word Teutons.

The German noun Reich is derived from Old High German: rīhhi, which together with its cognates in Old English: rīce, Old Norse: ríki, and Gothic: reiki is from a Common Germanic *rīkijan. The English noun is obsolete, but persists in composition, for example in bishopric. While usually translated into English as 'empire', reich more accurately translates to 'realm'.

The German adjective reich, on the other hand, has an exact cognate in English rich. Both the noun (*rīkijan) and the adjective (*rīkijaz) are derivations based on a Common Germanic *rīks "ruler, king", reflected in Gothic as reiks, glossing ἄρχων "leader, ruler, chieftain".

It is probable that the Germanic word was not inherited from pre-Proto-Germanic, but rather loaned from Celtic (i.e. Gaulish rīx, Welsh rhi, both meaning 'king') at an early time.

The word has many cognates outside of Germanic and Celtic, notably Latin: rex and Sanskrit: राज, romanized: raj, lit. 'rule'. It is ultimately from Proto-Indo-European *reg-, lit. 'to straighten out or rule'.

History

Ancient humans have been present in Germany since at least 600,000 years ago. The first ancient non-modern human remains were discovered in Neander valley, which is the namesake of the Neanderthal man, or Homo neandethalensis. Modern human remains have been found in the Swabian Jura, including 42,000 year old flutes which are the oldest musical instruments ever discovered. Other discoveries include the 40,000 year old Lion Man and the 35,000 year old Venus of Hohe Falls. The Nebra Sky disk, created during the European Bronze Age, is attributed to a German site and dates circa 1,600 BC.

Germanic Tribes

The Germanic tribes are generally accepted to have originated in northern Germany and southern Scandinavia, dating back to the Pre-Roman Iron Age or to the Nordic Bronze Age. They expanded south, east, and west, coming into contact with the Slavic, Celtic, Iranian, and Baltic tribes.

The Roman Empire under Augustus expanded into Germanic lands. In AD 9 three Roman Legions were defeated by Arminius. By AD 100, when Tacitus wrote Germania, Germanic tribes had settled along the Rhine and the Danube rivers, occupying much of modern Germany, except for Baden, Württemberg, southern Bavaria, southern Hesse and western Rhineland were incorporated into Roman Provinces. Around AD 260 Germanic speakers broke into Roman lands. After the Hun invasion in AD 375 and the decline of Rome in AD 395, Germanic tribes moved farther southwest: the Franks established a kingdom in Gaul and pushed east to subjugate Saxony and Bavaria. The areas that are now Eastern Germany were inhabited by Western Slavic and Baltic tribes.

East Francia and the Holy Roman Empire

Charlemagne founded the Carolingian Empire in 800; it was divided in AD 843 into West Francia, Middle Francia, and East Francia. The realm of East Francia served as the basis for Germany and stretched from Rhine in the west to the Elbe in the east and from the North Sea to the Alps, and from this territory emerged the Holy Roman Empire. The Liudolfings (919-1024) consolidated several major duchies. In 996 Gregory V became the first German pope, appointed by his cousin Otto III, whom he quickly appointed as Holy Roman Emperor. The Holy Roman Empire absorbed Burgundy and Northern Italy under the Salian dynasty (1024-1125), although these emperors lost power through the Investiture controversy

Under the House of Hohenstaufen (1138-1254) the German princes encouraged German settlement to the south and the east. This migration is called Ostsiedlung (literally east settling). Members of the Hanseatic League, consisting mostly of north German towns, prospered in the expansion of trade. The Great Famine of 1315-17 caused a decline in the population, exacerbated by the Black Death of 1348-50. The Golden Bull issued in 1356 provided the constitutional structure of the Empire and codified the election of the emperor by seven prince-electors.

The printing press was invented around 1440 by Johannes Gutenberg, starting the Printing Revolution and laying the foundations for the democratization of knowledge. In 1517, Martin Luther incited the Protestant reformation; the Peace of Augsburg in 1555 made Protestantism legal in the Holy Roman Empire but decreed that the faith of the prince was to be the faith of his subjects in a concept known as cuius regio, eius religio (whose realm, his religion). From the Cologne Wars through the Thirty Years' War, religious conflict devastated the German lands and significantly reduced the population.

The Peace of Westphalia ended religious warfare among the Imperial Estates; the largely German-speaking rulers were able to choose between Lutheranism, Roman Catholicism, and Reformed Christianity as their official faith. The legal system initiated by a series of Imperial Reformed (approximately 1495-1555) provided considerable local autonomy coupled with a stronger Imperial Diet. The House of Habsburg held the Imperial Crown from the election of Albert II in 1438 as the King of the Romans to the death of Charles VI in 1740. Following the War of Austrian Succession and the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle, Charles VI's daughter Maria Theresa rules as Empress Consort when her husband, Francis I became Emperor. From this the House of Habsburg-Lorraine was founded.

German Confederation

From 1740, dualism between the Austrian Habsburg monarchy and the Kingdom of Prussia dominated the history of Germany and German politics. Prussia, Austria, and Russia agreed to partition Poland among themselves in 1772, 1793, and 1795. During the French Revolutionary Wars, the Napoleonic era, and the final meeting of the Imperial Diet, most of the Free Imperial Cities were annexed by dynastic territories; the ecclesiastical territories were secularized and annexed. In 1806, the Holy Roman Empire was dissolved, and France, Prussia, the Habsburgs, and Russia competed for hegemony over the German states during the Napoleonic Wars.

Following the fall of Napoleon and the First French Empire, the Congress of Vienna founded the German Confederation, a loose association of 39 German-speaking states intended to replace the Holy Roman Empire. The Emperor of Austria was made the permanent president reflecting the Congress' rejection of the Kingdom of Prussia's rising influence. Disagreement within restoration politics is partly responsible for the rise of liberal movements, followed by new levels of repression by Austrian statesman Klemens von Mitternich. The Zollverein, a tariff union, furthered economic unity in the German states.

German Revolution and Unification

On 26 July 1844 Friedrick Wilhelm IV was assassinated by Heinrich Ludwig Tschech, the former mayor of Storkow, who believed that the Prussian monarchy had been responsible for his ousting from power. As the late king had no children of his own, he would be succeeded by his brother as Wilhelm I. Partially at the behest of his wife Augusta, Wilhelm I presented himself as a far more open and conciliatory monarch. As such the crown entertained liberal scholars and reformers, softening Wilhelm’s political beliefs in the coming years. In 1846 Wilhelm I appointed Gottfried Ludolf Camphausen as Minister President, finding him more agreeable than the councilors inherited from his late brother. Camphausen proved a moderate liberal who influenced the king toward reform, although he would prove still too hesitant to appease the country’s most radical factions.

In early 1848 revolution swept across Europe, with revolutionaries rising up in Prussia and other German states. These revolutionaries became loosely unified by pan-Germanism and discontent with the traditional, largely autocratic political structure of the German Confederation, which had been imposed on Central Europe since the end of the Napoleonic Wars. In Germany, the Grand Duchy of Baden became one such epicenter of revolution, when on 27 February an assembly passed a resolution demanding a bill of rights. The demand was followed in numerous other German countries, and in most cases was accepted when it became clear the strength of popular support. After violence broke out in Vienna, the princes of the German states partially relented to the protesters by approving a tentative parliament, which would be convened at the end of March at St. Paul’s Church in Frankfurt am Main. This assembly would be tasked with drafting a new constitution, which would be called the "Fundamental Rights and Demands of the German People." Dominated by monarchists, discontent in the early assembly led to a walkout, which forced the assembly to pass a resolution calling for an “All-German National Assembly”. This assembly would take shape on 18 May, elected under universal suffrage with an indirect, two-stage voting system, which had been legalized on 8 April.

Protests similarly broke out in the streets of Berlin in March, and Wilhelm I, taken by surprise, yielded to the demands for parliamentary elections, a constitution, and freedom of the press, and to pursue the merger of Prussia with the rest of Germany. After a series of resignations in the government of Prussia, Joseph von Radowitz emerged as chief minister, advocating for Prussia to legitimize and support the Frankfurt parliament in order to craft it into accepting union under Prussian leadership. The initial parliament was racked with indecision, as debates over Germany’s future government, issues of regionalism, inclusion of the German-speaking parts of the Austrian Empire, and foreign events stalled progress. Although he quelled opposition in Prussia, Wilhelm I kept his word and went ahead with a moderately liberal constitution, albeit one that preserved much of the monarch’s powers. Alarmed by the state of affairs, the Prussian government approved a rapid expansion of the military budget and of recruitment.

Eager to repair Prussia’s prestige after the protests in Berlin, and urged on by nationalist military advisors such as Joseph von Radowitz, in April 1848 Wilhelm I declared war in support of German nationalists in Schleswig-Holstein, who protested the overlordship of the Kingdom of Denmark. The war came as a result of a careful diplomatic balancing act; Russia and the United Kingdom posed major qualms with German domination of the Danish straits, but were persuaded to support a Prussian-dominated Germany at the expense of France, as long as Prussia vowed to not enter Jutland past the duchies. Prussian intervention would be timed after the Frankfurt convention had voted in favor of it, which inadvertently improved the legitimacy of the parliament. Leading Prussian general Friedrich Graf von Wrangel would later assert that he was subservient to the new central government, and proposed that any treaty be presented for ratification to the German National Assembly. Although initially he gave his tentative blessing toward the war, by early 1849 Nicholas I of Russia was prepared to intervene in favor of peace, as he found Prussia’s acceptance of the Frankfurt parliament “disgusting”. Seeking to make a quick peace, the Germans agreed to a truce on 8 June 1849, as negotiated by the British. The final agreement saw Schleswig split between Denmark and the Germans, while Holstein was recognized as a member of the German Empire from Frankfurt. This treaty would be highly controversial, further flaming tensions between Prussia, Russia, and Austria.

All the while negotiations for the future German state continued. In March 1849 the Alliance of the Three Kings would be signed between Prussia, Saxony, and Hanover, as a tentative agreement to defend the new German state, although the latter two obtained a clause allowing their departure from the alliance should the rest of the German states (sans Austria) reject union. Reassured by Radowitz, on behalf of the Prussian and conservative delegations, the parliament at Frankfurt would finish drafting a constitution in November 1848, and in early 1849 the hereditary title of “Emperor of the Germans” was offered to Wilhelm I, who reluctantly accepted. Under the threat of Prussian military force, most of the states of northern Germany acquiesced to this arrangement by mid 1849.

These developments greatly angered the Austrian Empire, but up to this point was incapable of intervening. Austria would face rebellion in Austria itself, war with the states of northern Italy, and a revolution in Hungary, which would not all be settled until late 1849, the latter of which only with Russian military intervention. The handful of states that had unilaterally crushed rebel sentiment and were apprehensive about union – chief among them Bavaria – now looked to Austria to rebuild the German Confederation, with force if necessary. In Hesse, the prince-elector Friedrich Wilhelm aligned himself with the Austrian government in defiance of his nation’s parliament, hoping that military force would be used to reassert his control over the nation. This proved an immediate crisis for the Frankfurt government, who viewed Hesse’s actions as illegal, as well as for Prussia, as Hesse could block Prussian movement to its Rhineland territories. The situation escalated in early 1850, as Austria demanded that Prussia vacate its occupations in the German states. This proved an unbearable and insulting imposition; Wilhelm I responded with a fiery speech to the nation’s parliament and a general mobilization.

In late 1850 negotiations began in Warsaw, orchestrated by Austrian foreign minister Felix Fürst zu Schwarzenberg, which was attended by Russian and German delegates. At their most zealous, the Austrian delegation sought to have the German Confederation returned; the Prussian government considered an abdication of the German title untenable. Not only would such a renouncement be embarrassing for the Prussian monarch, it would undoubtedly lead to democratic uprisings in Prussia. Despite the precarious position of the Frankfurt assembly and the constant infighting, the assembly approved the need for a national army and navy. The Federal Army (Bundesheer) was largely an expansion of the German Confederation’s previous arrangement, in which each state would volunteer a certain number of soldiers, but only in the case of defense, and these forces would be placed under the joint command of the Prussian leadership in war time. Collectively, the German states sans Prussia mobilized 170,000 soldiers by 1850, which had been tasked with restoring order across the region.

Concurrent to this crisis, the fallout from the Don Pacifico affair soured relations between Britain and Russia. The Lord Palmerston government in Britain generally favored limiting the power of Russia, as Britain feared Russian expansion westward could encroach on British interests in the Middle East or in continental Europe. The election of the future Napoleon III as President of France proved a much more immediate threat than possible war in Germany, with Palmerston hoping that France could be made an ally, which would free Britain’s diplomatic hand elsewhere in the world. Likewise, Napoleon III needed to assure the rest of Europe that "The Empire means peace" ("L'Empire, c'est la paix"), and so negotiated neutrality in the German conflict, while pivoting toward the British. In a private meeting between Napoleon III and the new foreign minister for the Germans, France secretly promised neutrality.

At a standstill diplomatically, and with assurances from Russia, on 24 March 1851 Austria declared war on Prussia and launched an invasion. Although Wilhelm I favored a diplomatic resolution, Austria striking first proved advantageous, as he was able to rally support among the fledgeling German Empire that they were defending themselves against foreign aggression. The invasion proved a crucial step in national unity, helping to rally support among the German people and to solidify the Empire as a cohesive state. In the opening stages of the war, the Prussian army focused on the defense. The nation was able to concentrate a local plurality of soldiers on the border in response to the Austrian invasion, and although not widely adopted by the army as a whole, the use of the Dreyse needle gun provided a technological edge.

The first center of the war proved to be Hesse. Despite an initial defeat at Hofgerismar, the Prussian army would overwhelm Hessian resistance with overwhelming numbers by April. An Bavarian-Austrian invasion would be halted at Stolberg on 20 April and Langensalza on 13 May, securing Saxony. A fierce campaign would take place along the River Main in defense of the legislative capital at Frankfurt. The national assembly would call for mobilization of the Empire in response. However, Bavarian forces would be repulsed from the outskirts of the city by May, allowing a counterattack that reached the Bavarian fortress at Würzburg. A siege would take place here that lasted until the end of the war. Russian forces were slower to mobilize, but by that summer 300,000 soldiers were in position to strike at Prussia, split between north and south. Prussia would successfully repulse Russia’s invasion of East Prussia at Possenheim; the offensive was abandoned in September with the Russians suffering some 46,000 casualties, including 20,000 men captured.

Although tempted to expand the war by pushing further into Austria, and to demand greater territorial concessions, Wilhelm I was persuaded to not escalate the conflict, for fear of further intervention from the rest of Europe, as well as an “unnecessary bitterness of feeling or desire for revenge”. Negotiations reopened in 1852, and the following spring a peace was signed. The defeated parties were forced to acknowledge the London Protocol regarding Schleswig-Holstein, and to recognize the proclamation of the German Empire. Minor rearrangement of the borders of the German states took place, but both Austria and Russia were left intact territorially. The remaining states of Germany were forced to accept a military alliance with the German Empire, and began negotiations for peaceful integration into the Empire, under the condition of limited autonomy. On 4 April 1853 the Treaty of Vienna was formally signed.

Geography

Climate

Government and politics

| Germany |

This article is part of the series: |

|

|

|

Other courts: |

Germany is a federal constitutional monarchy and a parliamentary democracy. The current Constitution of the German Empire (Verfassung des Deutschen Reiches) has been the foundation of the German political system since its adoption in 1871 and was significantly modified in 1975, during the reign of Emperor Louis Ferdinand (1951–1994). Amendments to the constitution require a two-thirds majority in both houses of the parliament; the fundamental principles of the constitution such as the monarchy, the federal structure, rule of law, separation of powers, and the articles guaranteeing human rights and dignity are valid in perpetuity.

According to the constitution, which was modified from the original 1871 constitution drafted by Otto von Bismarck, the empire is a federation (federally organized national state) of 25 constituent states, one of which is an overseas territory. Prussia, the largest and most powerful state, has the permanent presidency within the federation as the King of Prussia is also simultaneously the German Emperor. By tradition, the German monarch uses the title King of Prussia while dealing with the governments of other German states and uses the title German Emperor while dealing with foreign nations as the representative and head of state of the entire German Empire. Since the enactment of the 1975 amendments to the constitution, the German Emperor is a ceremonial head of state and a symbol of the nation, and while the constitution still grants the monarch "reserve powers," in practice his role in day-to-day politics is limited as a constitutional monarch. The same principles also apply to the monarchs of the constituent kingdoms, duchies, and monarchies of the Empire.

The head of government and de facto leader of Germany is the Imperial Chancellor (Reichskanzler), who is appointed by the majority party or coalition government in the Reichstag (Imperial Diet). The Chancellor leads the Council of Ministers and is also the chairman of the Bundesrat (Federal Council), the council of representatives from all 25 German states. Prior to 1975 the Chancellor was appointed by the Emperor and responsible only to him, since then the Chancellor has been chosen by parliament and is responsible to the elected representatives in the Reichstag. In effect, the traditional role of the Emperor in German politics is to a degree exercised by the Chancellor of the Empire.

German constitutional law established the Reichstag as a house of representatives of the German people directly elected by universal suffrage, similar to the House of Commons of the United Kingdom or the House of Commons of Sierra, and the Bundesrat as a council of delegations from all German states to represent them on a federal level, being a de facto upper house. Although the latter is not officially part of the parliament but is a "second chamber beside the parliament," it is widely regarded as the upper house and has been compared to the British House of Lords or the Sierran Senate. Imperial laws are enacted by a simple majority vote in both the Reichstag and the Bundesrat, and take precedence over state laws. There are 598 seats in the Reichstag and 70 seats in the Bundesrat.

Constituent states

The German Empire is administratively organized into 25 constituent states, which include five kingdoms, eight grand duchies, four duchies, two principalities, four free cities, and one imperial city, and two imperial territories (New Guinea and Qingdao). Most of these states are constitutional monarchies, while the free cities have a republican form of government, and the City of Berlin is managed directly by the Imperial government. In practice, each state is a democracy with an elected state parliament (Landtag) and a head of government, the Minister-President. The territory of New Guinea is headed by a locally elected governor. Prussia is the largest federal state, covering two-thirds of the empire's territory.

The majority of these states largely had de facto sovereignty since the 1600s while being part of the Holy Roman Empire, while others were created by the 1815 Congress of Vienna. The borders of states are often not contiguous, often based on the territories owned by particular ruling families. During the 20th century the borders were changed and several new states were created.

| State | Capital | |

|---|---|---|

| Imperial City (Reichstadt) | ||

| Berlin | ||

| Kingdoms (Königreiche) | ||

| Prussia (Preußen) | Königsberg | |

| Bavaria (Bayern) | Munich | |

| Saxony (Sachsen) | Dresden | |

| Hanover (Hannover) | Hanover | |

| Württemberg | Stuttgart | |

| Grand Duchies (Großherzogtümer) | ||

| Baden | Karlsruhe | |

| Hesse (Hessen) | Darmstadt | |

| Mecklenburg | Schwerin | |

| Westphalia (Westfalen) | Dortmund | |

| Thuringia (Thüringen) | Erfurt | |

| Rhineland (Rheinland) | Mainz | |

| Oldenburg | Oldenburg | |

| Luxembourg (Luxemburg) | Luxembourg City | |

| Duchies (Herzogtümer) | ||

| Alsace-Lorraine (Elsaß-Lothringen) | Strasbourg | |

| Schleswig-Holstein | Kiel | |

| Brunswick (Braunschweig) | Braunschweig | |

| Nassau | Wiesbaden | |

| Principalities (Fürstentümer) | ||

| Lippe | Detmold | |

| Waldeck | Arolsen | |

| Free and Hanseatic Cities (Freie und Hansestädte) | ||

| Bremen | ||

| Frankfurt | ||

| Hamburg | ||

| Lübeck | ||

| Imperial Territories (Reichsländer) | ||

| German New Guinea (Deutsch-Neuguinea) | Friedrich-Wilhelmshafen | |

| Qingdao (Tsingtau) | Tsingtaustadt | |

Foreign policy

Military

Law enforcement

Economy

Infrastructure

Science and technology

Demographics

Education

Health

Culture

Notes

- ↑ German: Deutsches Kaiserreich, officially Deutsches Reich, meaning "German Reich" and conventionally translated as "German Empire."

See also

| This page uses material from the Wikipedia page Germany, which is released under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License (view authors). |

| This page uses material from the Wikipedia page German Empire, which is released under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License (view authors). |